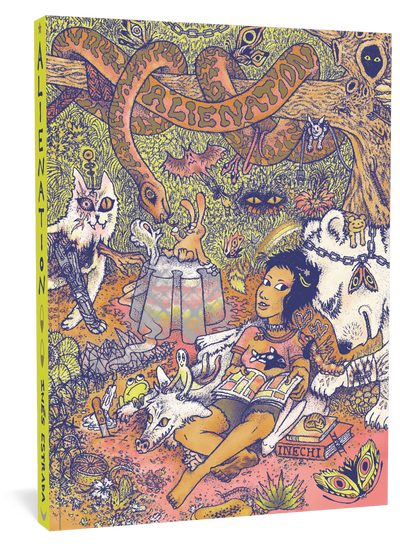

Alienation: A Graphic Novel by Ines Estrada

Reviews

By Andrew Mullins

Since I read Ines Estrada’s Alienation, I’ve been looking at beachfront property in Alaska. Not to live there. Ms. Estrada’s graphic novel got me thinking the investment could eventually pay off. Technically, the story is set in the future, although things haven’t changed all that much. Hers is a world perpetually on the brink of disaster. In this respect, Alienation does what all the best dystopian stories do: it paints a bleak picture of the future to speculate about how fucked we are as a society.

Rather than confronting the disastrous possibilities of climate change, we fled the rising oceans and settled near the Arctic Circle. One reason doomsday was shrugged off so easily is because our #bestlife is lived online. Eliza and Charly live in a sterile apartment furnished with little more than a biometric shower and some sort of cylinder from which they order sushi pizza. Eliza immerses herself in MMORPGs (*inhales* massive multiplayer online role-playing games *exhales*), picking flowers and talking through her problems with NPCs (Non-Playable Characters you can chat with, kill, or both). Meanwhile, Charly is busy rocking out to holograms of Johnny Thunders and the Heartbreakers. Eliza and Charly love and support each other, even though most of their time is spent deep inside a highly personalized, simulated reality. Eliza, an Inuit, feels disconnected from the ancestral roots of her grandfather. A similar rift divides Charly, a Latino from Los Angeles, and his abuela. All this goes to show how technology isolates them and, more subtly, erodes difference.

Humanity faces a new peril, though, with artificial intelligence. Eliza ekes out a living as a dancer at an online strip club. When an overly smitten patron insists on a private show, she senses something is amiss. At first she thinks it’s a glitch in the biometric system—fittingly dubbed Googlegland—installed in her brain. Turns out, it’s no glitch. Eliza has been “chosen” as the mother of the first-ever trans-human baby. The scenes of sexual violence are disturbing not just because the attacker assaults her body, but because the attacker is a freakish drawing of an internet cloud. Nothing about the rape feels real to her until she logs back in and learns the NPCs are complicit in the attack. Not only that, the mix of terror, disgust, and betrayal she feels puzzles these cyber-creatures. To them, it’s an honor to carry the Christ-child of the digital age. In this chilling vision of the future, going online, escaping the brick-and-mortar world, is no longer a choice.

Estrada balances the sparely drawn human world with vivid panels of virtual reality, packed with HTML text and other web graphics that are both familiar and alarming. Smiling cartoons with wires protruding from their legs appear as grotesque renderings of friendship. Alienation could be called cyberpunk, I suppose, although it avoids the sexy allure of chrome cybernetic enhancements. Estrada takes a far more political approach, pushing the premises of climate change and transhumanism to logical extremes. As her characters drudge aimlessly through a post–global warming, post-human world, perhaps the real horror is the insinuation that the future won’t change our lives, for better or for worse. We don’t build a better society or get wiped off the face of the planet. Instead, we simply coast right along, becoming something other than human, all while treading water in Alaska.

More Reviews