Fiction

“You remember that guy Mickey Mikalski, used to hang out with Nick DeSantis?”

“Had a split lip.”

“Hare lip. Had an operation to fix it. He’s been tryin’ to grow a mustache to cover up the scar but hair won’t grow there.”

“What about him?”

“He got nabbed boostin’ a car. Drove it through a fence, how the cops caught him. Winky Wicklow says his uncle Bob, who’s a cop, thinks Mikalski’ll get five years at Joliet ’cause he ain’t a minor no more.”

“That’s rough.”

“You know what the Arabs do to a horse thief?”

“What?”

“Cut off one of his hands so he has to eat and wipe his ass with the same hand.”

“Who told you that?”

“My dad. He heard about it when he was in Morocco.”

“Are he and your mother back together?”

“Sort of. He’s been traveling a lot lately.”

Roy and his friend Tommy Cunningham were sitting on the front steps of Tommy’s house on a Saturday morning.

“It’s gonna rain,” said Tommy. “I don’t think we’ll get to play the game this afternoon. Which would you choose, Roy, five years in prison or lose a hand?”

“Be tough to play ball one-handed.”

Tommy nodded. “I’d rather have a car than a horse.”

“What’s that about a horse?”

Tommy’s mother stepped out of the house onto the front porch.

“Morning, Ma. I just told Roy I’d rather have a car to ride around in than a horse.”

“Good morning, Mrs. Cunningham,” said Roy.

“I liked to ride horses back in Ireland when I was a girl.”

“Gee, Ma, you never told me that before.”

“It was a long time ago, in my ghost years, that time in your life you don’t know won’t never come again. I remember my favorite, Princesa. She had Spanish blood, belonged to a farmer down the road from us. He let me ride her after school and on Sundays after church.”

“Not on Saturdays?”

“Saturdays were for marketing and chores. Now it’s every day and it’s only police who ride horses in Chicago. What’re you fellas up to?”

“We’re supposed to play a ballgame against Margaret Mary’s at Heart-of-Jesus, but looks like we’ll be rained out.”

“I could use a hand with the laundry.”

Roy stood up.

“I’ll see you at the park, Tommy, if it clears up. Bye, Mrs. Cunningham.”

On his way home Roy thought about what Tommy’s mother might have been like as a country girl in Ireland before her family moved to Chicago. She was a strong, heavyset woman now, with bright blue eyes and thick red hair. Her face had deep creases on the cheeks. Roy’s mother, who was a few years younger than Mrs. Cunningham, had no lines on her face and she was much slimmer, but she was always nervous and worried about something. Mrs. Cunningham always seemed calm and spoke in a gentle way to Tommy and his brother Colin. Maybe his mother would be calmer if she had spent her childhood in the country and had a horse to ride instead of living in a big city and then being sent away to boarding school.

The sun was trying to break through the clouds. Roy decided to get his glove and go to the park even if it started to rain. On his way there he spotted a powder-blue Cadillac getting gas at the Mohawk station across Ojibway Avenue. His mother was sitting in the front passenger seat next to a man Roy did not recognize. The man was wearing a brown fedora and a beige trench coat, the kind private investigators wore in the movies. He was talking to Roy’s mother and she was looking out the closed window on her side. Roy watched her for a minute until the attendant stopped pumping gas. The driver paid him, started the car, and pulled out of the station. Roy’s mother kept staring through her window.

His baseball cap was wet and water was leaking through into his hair but Roy began walking again toward the park. He was certain his mother had not seen him.

At the park six blue-and-whites were parked at a variety of angles in the street in front of the entrance Roy commonly used. A few people were gathered on the sidewalk in front of a line of several policemen who were blocking the way.

“What’s going on?” Roy asked a man wearing a Cubs hat and a green tanker jacket.

“There’s a dead body lyin’ on the pitcher’s mound. A kid, someone said.”

“Did you hear the kid’s name?”

“No. The cops aren’t givin’ out any information. They might not know yet.”

Tommy Cunningham punched Roy in his left arm.

“All these people here to watch our game?”

“Thought you were helpin’ your mother with the laundry.”

“I did. Somebody get shot?”

“Maybe. There’s a dead kid on the mound.”

“You’re jokin’. Who told you that?”

“Guy over there. Cops won’t let anyone into the park.”

“Let’s go around to Kavanagh’s house and go in through his backyard.”

The boys ran around the block, cut through Terry Kavanagh’s yard into the alley, and crept up a dirt path where there weren’t any cops. A bunch of men were standing around the infield, a couple of whom were taking photos. Tommy and Roy kept their distance and half hid behind a large Dutch elm tree. An ambulance drove into the park and stopped next to the first-base foul line. Two male attendants wearing white coats and trousers jumped out, opened up the back doors of the ambulance, and pulled out a stretcher. The men on the infield parted to let them through but not enough so that Roy and Tommy could see the body on the mound. It was ten minutes before the attendants carried out the stretcher. The corpse was covered with a white sheet, but as it was being loaded into the ambulance the stretcher tilted and the sheet slipped off the face.

“It’s Louie Fortini,” said Tommy, “Artie Fortini’s older brother. Remember him? He must be about twenty years old. He was a pitcher, had a tryout with the Braves but didn’t get signed.”

“You sure?”

“Yeah. He and Artie both got big hook noses. It’s Louie for sure.”

The ambulance drove out of the park the way it came in. Rain fell harder and some of the men walked off the infield.

“I wonder if his family knows,” said Roy.

“The cops probably called them. They’ll have to identify the body.”

There was a flash of lightning followed by thunder.

“Let’s get away from this tree,” Roy said.

The next day there was an article in the Sun-Times about the dead boy. Louie Fortini had shot himself in the head with his father’s gun, a Luger Anthony Fortini had taken off a fallen German soldier during the war and kept as a souvenir. Louie had been a day shy of his twenty-first birthday. In the article his father was quoted as saying that his son had been depressed ever since his unsuccessful tryouts for major-league baseball teams.

On their way to school Tommy said to Roy, “I wonder if he tried out for the Cubs. He could throw a screwball. I saw him throw it in high school.”

“Artie would know.”

“Man, I’d never kill myself. What about you, Roy?”

Roy remembered his mother once saying that if things got any worse she’d commit suicide.

Before he could answer, Tommy said, “Do you think Louie told Artie he was thinking about shooting himself?”

“We shouldn’t ask him that,” said Roy. ![]()

Barry Gifford is the author of more than forty published works of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, which have been translated into thirty languages. His most recent books include Ghost Years, The Boy Who Ran Away to Sea, How Chet Baker Died, Roy’s World: Stories 1973–2020, and Sailor & Lula: The Complete Novels. He cowrote with David Lynch the screenplay for Lost Highway. Wild at Heart, directed by David Lynch and based on Gifford’s 1990 novel, won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1990. Gifford lives in the San Francisco Bay area.

The story appears in Gifford’s new book, Ghost Years, out this month from Seven Stories Press.

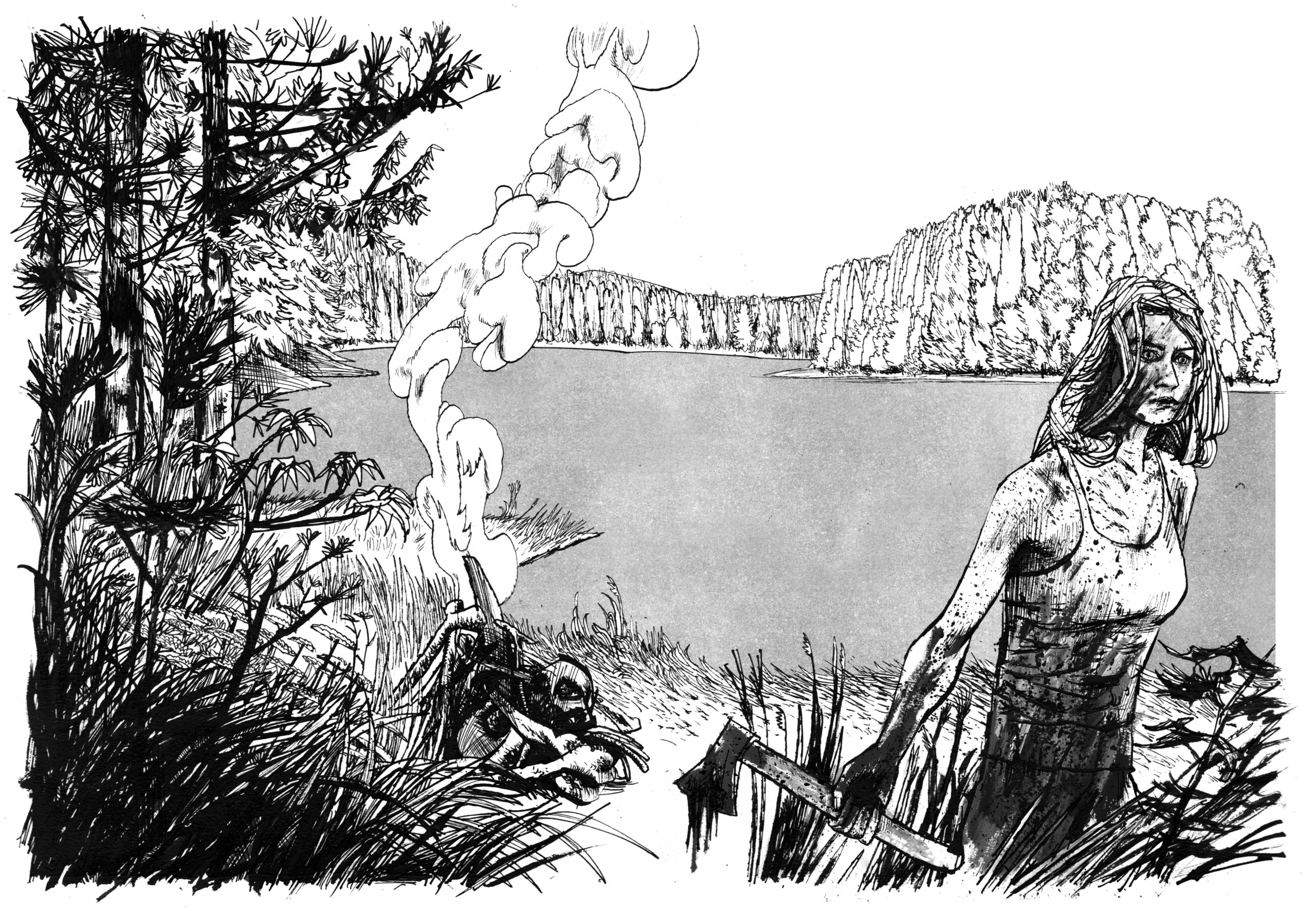

Illustration: Barry Gifford.

It’s in the morning that the sun comes around the massive guava tree, above the electric fence, and, as a narrow beam of light, touches Selene’s face as she lies in bed with the tips of her toes against the top bunk. Every day, she waits for this sunbeam, which, on blue-sky days, arrives punctually through a barred window measuring just thirty by thirty centimeters, into the cell shared with three other women. Over forty minutes, it shifts, millimeter by imperceptible millimeter, from Selene’s face to the wall before vanishing.

Everything happens slowly when you’re behind bars. The torture of being jailed is compounded by the torture of emptiness, the total absence of anything to do. Selene has already counted how many times her heart beats in an hour. She’s collected cigarette butts from the courtyard and halls. Using an old world map that some prior inmate left behind in the cell, she started learning by heart the names of countries and capitals. Selene doesn’t get visitors. Ever. Since her arrest, her husband, mother, siblings, none of them has come to see her. She doesn’t miss them. She doesn’t miss anyone. She feels empty most of the time. When asked about her crimes, she shrugs. At times, she can be seen crying discreetly. No one knows if she’s sorry. She doesn’t say.

She bites her tongue most of the time. She smokes most of the time. She cleans the kitchen every day after lunch, scrubbing the walls and floor hard. Always hard. Because this is how Selene does everything in life. Hard. The extra pounds concentrated in her belly and flanks leave her arms dangling on her body. Walking is hard, just as breathing takes effort when she gets bronchitis. If it weren’t for the dark purple lipstick on her lips and the big silver earrings, you’d say she didn’t care about her looks at all. She’s rough: in her soul, in how she talks, in how she walks, in how she eats.

She bore two kids. She hasn’t heard anything about them since she was arrested. They’re twelve already. Twin boys. Identical. Though not that identical for Selene. She doesn’t tell them apart by how they look, but by what they’re like. On one of her boys, she can smell death. It’s her smell, too. The family thinks that raising the boys far away from their mother means they won’t be influenced. Selene knows that one of her boys is already doomed, just like her, to be no good. Could be karma or genetics—doesn’t matter. She’s their mother. She knows what grew inside her. She knows what’s good and what’s bad inside her.

Selene doesn’t have friends in prison. She prefers being feared. Still, she has the best bed in the cell, complete with a daily strand of sun. She even gets lunch leftovers when she cleans the kitchen.

As she peruses the world map, she wonders what exists beyond the small, miserable places she’s seen. Her pointer finger travels along the delicate, meandering lines dividing countries and continents. Locked up, Selene carries the whole world in her hands, tracing an imaginary line that crosses borders and takes her everywhere. The cell door unlocks. It’s time to go out for some sun, look at the sky, and wait for the day to end. ![]()

Ana Paula Maia (Brazil, 1977) is an author and scriptwriter and has published several novels, including O habitante das falhas subterrâneas (2003), De gados e homens (2013), and the trilogy A saga dos brudos, comprising Entre rinhas de cachorros e porcos abatidos (2009), O trabalho sujo dos outros (2009) and Carvão animal (2011). Her novel A guerra dos bastardos (2007) won praise in Germany as among the best foreign detective fiction. She won the São Paulo de Literatura Prize for best novel of the year in 2018 for her novel Assim na terra como embaixo da terra and in 2019 for Enterre seus mortos.

Padma Viswanathan is a writer, playwright, translator, and journalist. Her most recent book is Like Every Form of Love: A Memoir of Friendship and True Crime. She is the author of two previous novels: The Toss of a Lemon, shortlisted for the Pen Center USA Fiction Prize, and The Ever After of Ashwin Rao, a finalist for Canada’s Scotiabank Giller Prize. Her translation of the novel São Bernardo (2020), by the Brazilian writer Graciliano Ramos, was shortlisted for the Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize and runner-up for the UK Society of Authors TA First Translation Prize.

One night she was woken by a noise coming from one of the living room windows. Of course, it was nothing. But she wasn’t yet used to being alone in that big house and was easily frightened. Before going back to bed, she went to the kitchen for water. She didn’t have her lenses in and everything was a confused blur, shadows within shadows. She thought it must be about three, maybe four in the morning because she was emerging from a dense fog of disconnection. Her senses were divorced from her body and she found it hard to make her way. The cat appeared behind her and arched its back as if its stomach were about to shoot off an arrow toward the center of the earth. It purred its confusion, demanding breakfast from between her legs, and she almost tripped over it.

When she opened the refrigerator and the white pearl lit up the rectangle—the green floor, the marble worktop, the faucet, and all the other things that stood silently like grazing cattle seen in the distance—she saw a dark form on one of the blue wall tiles. The glasses were on that side of the kitchen. She’d intended to feel for one in the dish rack but was so deeply in the grip of the fear that had woken her, so prepared for disaster, that she decided to go back to the bedroom to put in her lenses before doing anything else. The cat jumped onto the bed again. She returned to the kitchen and realized that the dark shape was a slug. Had that repulsive mollusk been inside the glass? Best not to use it now and, in the morning, rinse it out thoroughly. She grabbed the plastic bottle filled with water from the faucet that had been chilling in the fridge. As she walked along the hallway, she took a swig from the neck. The thought that she’d come close to touching the slug, that it was still there, made her shudder. But it surely couldn’t, or so she imagined, move very far.

In the morning, there was no trace of it. She put down a bowl of food for the cat, then she wiped the sticky-sweet smear on the worktop with detergent and then bleach. And her day went by as other days had, and that night she went to bed but couldn’t sleep. One thing after another passed through her head as if her skull were a miserable black hole. The same gravity that kept her stable, propped against the pillow, began to press down on the images entering her mind, crushing them flat. Perhaps they were clips from other people’s heads, and as those people were able to sleep, the clips had taken up residence in hers, with all its available electricity.

She got up to make herself a cup of lime flower tea. Just in case, she put in her lenses and found her slippers. And in the flickering of the cold strip light, she saw three of them. White light fell on the room with the conclusiveness of a thing that in itself is wholly itself, and she immediately knew that this had been going on before, but as she never used to wake in the night, she hadn’t been aware of it.

When he was living in the house she’d slept soundly, straight through until her cell phone alarm rang. And she sometimes even allowed herself the luxury of ignoring it. Her love was the shell of that amazing mythical turtle that carries on its back elephants, which in turn carry the whole flat world on theirs. And she used to be there, on that fine, safe Tetris. These days, just to have company, she didn’t let the cat out at night, even though it woke up before her and bit and scratched to get whatever it wanted, and she’d be forced to further interrupt her sleep putting it out. And by then the sun would be rising, and what was the point of keeping up the charade? The presence of the cat didn’t make her any less alone. Yet, at that moment, she was glad it was there, and in some way expected its assistance. If it ate moths and flies, maybe it could also save her from this.

She spotted a slug on one of the wall tiles. Was it the same one? It was very close to where she’d seen the last one. There was another on a plate, bottom sweeping. She swore she’d never use that plate again, would smash it on the patio if necessary, even if it did belong to him. And the last slug, almost indistinguishable from the collection of stones on the worktop, was only inches from the microwave. She had no idea what to do. Not just one, but three slugs! She grabbed a can of Raid and sprayed.

The following day, she found nothing and was certain that they must be nocturnal. And that they had teeth, even on their tongues. At three in the morning, after waiting a reasonable time, she went exploring again. The number had doubled. One was climbing up the tall cabinet and another was even perched on the side of a knife she’d left to dry.

Google said: if you put out a glass of beer, the slugs go for the yeast and die, stupefied by their thirst.

So she bought some beer. She drank a little that evening, with the cat squirming in her lap as she watched one of the movies he’d always vetoed. There was still quite a lot left; she’d never really liked beer. She placed the glass in front of the stove, in the middle of the green kitchen floor gleaming with bleach. And that night she slept through without waking. It was the alcohol, or weariness, or just one thing on top of another. In the morning, she got out of bed and went straight to the kitchen to brew the maté, without putting in her lenses or even remembering her little homemade trap. That was when her bare feet collided with the glass.

Ah, they were the source of her revulsion. Not the rest of it.

She cried a little, unsure whether it was for the slugs, her home, or him. For herself. So, she cried for quite a long time, as if it were a form of entertainment or her tears were some kind of watery celebration. Maybe it felt good to have a more trivial excuse for feeling low. Something that wasn’t, for just one minute, her stupid heart that had plummeted down from cloud nine.

That night, when she woke to make an inspection, she found a dozen. Had her attack made them multiply or had they called up a secret army? Where had they all come from? How did they manage to reproduce so rapidly? Long, moist, sturdy bodies littered surfaces in outlandish, defiant positions. She thought she’d go crazy with disgust. She took salt from a cupboard and, without discrimination or even direction, began to sprinkle it about. The white, impalpable shower martyred several, but not all the slugs. When they began to dissolve, she felt her stomach churn.

As she had no desire to clear up dead slugs from among the living ones, she went back to bed, closed the door, and stayed there with the cat. Her brain was working along these lines: if I fall asleep, it will all die for a while and so will I, and maybe tomorrow something will have sorted out the night for me.

She’d also had those kinds of thoughts when he was still with her, in the big house they had fixed up, painted, and redesigned together. The house they had filled with marvelous objects; objects she now observed in the same way the glass eyes of those stuffed animals some people have on their walls observe their surroundings. Except that these days those objects seemed lifeless. The invading slugs were more alive.

Despite her heaving stomach, she put on a pair of rubber gloves, poured more bleach on the floor, and set to work with the mop and cloth. The cat was mooching around, hoping to find something useful. She disinfected. Then, one by one, she opened all the compartments in the kitchen, moving the saucepans, plates, Tupperware containers, jars, and packets. The cat happily nosed about in those hiding places. But, like someone returning from a restful vacation, it brought back no news. Where were they coming from? Where did the slugs spend the day? How did they get into the kitchen? Or were they already hidden there, camouflaged, when she was walking around restlessly, making noise, and the sun was progressing from one window to the next. She wanted to find their origin.

And so the days passed. One after another, all seemingly alike. Every time she opened the front door, she expected to find him there. When he wasn’t, she felt as if a hammer were knocking her into the floor with a single blow, flattening her to the surface. She cried into his shirts, into the curtains, with her nose in the cap of the bottle of cologne he’d left behind. She hugged the jackets on the clothes hangers in the walk-in closet—they were at almost the same height he’d been during all those years, receiving her with love. She talked to the cat, talked to herself. Neighbors asked cruel questions. But then, is there really any question that isn’t, in essence, an act of cruelty, a test of resilience? She scrutinized those neighbors at lunchtime, watched the cars pass by outside, watched the buses pass by, the sun pass by, the clouds pass by. She lay on the big bed and listened to the creaking in her temples, old wooden stairs that her ghosts ascended. She rehearsed conversations and was filled with rage. Her anger was a way of avoiding the pain.

It was only at night that she thought of the slugs: when she got out of bed to check—now without the energy to do anything about them—if they were still multiplying. The cat growled at them, its jaw trembling; she’d seen it like that once before, when it had killed a pigeon on the roof and then hidden it as a present under a plant in one of the flowerbeds. He’d picked it up by its bloodied wing and put it in a bag. But the cat did nothing more than growl. What could it do when faced with slugs? She wasn’t any better.

The number doubled every night. She could no longer count them.

They had taken on the communal form of a tide, and now reached halfway across the kitchen floor and up the wall tiles. Piled on top of one another, they gave the impression of being about to pronounce, in unison, a single word, perhaps a name. She thought it strange that a formation of that size didn’t emit any sound. She considered trying the salt again, but already knew what would happen the next day. She considered calling someone, but the truth was that she didn’t want to talk to anybody, not even to give instructions. She wondered again during the day about where all those slugs went. She checked the whole house. Nothing anywhere. But things were different in the daytime, her mind was occupied with the hologram of the last time she’d seen him, in the garden, his back turned to her.

And there were all kinds of other, ordinary things to occupy that mind: her accounts, the rent, repairs, the future, her horoscope, which hadn’t been at all positive lately, and the advice that arrived in bunches of inutility, and the messages—disguised commiserations—from friends, and the assistants in the bakery across the road who corralled her with their suggestions. Even so, she’d get out of bed to check on the slugs’ progress, wanting to know the extent of the hell that was expanding in her kitchen. She used lipstick to draw lines on the floor, the way you mark the wall to record a child’s growth. The next night, there would be many more, the red line already swamped by the tide. The kitchen was a huge blob, an oleaginous river occupying every space, right up to the ceiling. She’d stand before it and watch those quivering, living creatures, their feelers, the outline of their soft internal shields. They were an enormous stagnant animal: some higher power controlled those gelatinous individuals. What was to be done? She had no idea, and so she did nothing.

One night, she found that they had reached the dining room and crawled up onto the chairs and the table. She wept a little, but as tears were now nothing unusual for her, she went back to bed. The cat, twisting and turning at the end of the mattress, no longer even bothered to wake for these inspections. In the morning, they had vanished again. She prepared the maté and walked through the now empty rooms. She watered the plants. Nothing.

Some days later, their advance had reached the living room, but, like floodwater, the current took an unexpected turn and, instead of covering that large space, veered into the hallway leading to the bedroom. He’d come around to take away items of furniture and pack the things in his drawers. He’d taken, for instance, the shirts she used to cry into.

She made mental lists of the empty spaces around the house. Where there had been armchairs, the coffee table, the huge television they had inherited, the magnificent bronze lamp, were now disturbing absences. She stared at the things she could no longer touch and couldn’t overcome her astonishment. The cat was confused. It meowed, demanding the comfortable chair where it lazed away the afternoons. She meowed a little too, just to try it out, but nothing of what had been taken reappeared.

By the time she recovered sufficient energy to check on the slugs in her drowsy state, the most daring were lapping up against the bedroom door. She stood before them and saw that, farther back, the joints between things were moving crazily. She raised the blinds just a few inches, opened the window to let in fresh air, and returned to bed. There were so many of them! What did they want?

The following day, everything was dry. Almost clean. But anyway, she wiped the surfaces with bleach, until the bottle was empty. Then she went to the store for more. She also bought fruit, wine, bread, and cheese. Things like that, which she put in the refrigerator. She fed the cat.

Each night, she serenely observed how their boundaries extended. She took everything from the floor, rearranged her shoes. She washed clothes, swept under the bed, and realized that the floor down there was thick with dust. How long had it been there? And, come to that, where did it all come from? Who made it and where? Who dropped it among the people, furniture, slugs? She piled up the three coins she found to give them some meaning.

That night, she got up and saw that they were at the foot of her bed. She was lying diagonally, no longer keeping to her own side. Two days later, although every surface was by then covered, they were still creeping over the floating flooring they had chosen together; pale, gleaming wood to reflect the daylight. Would the flooring be ruined? It wasn’t supposed to get wet. The seams between the planks would open up. They’d been warned that humidity damaged it. From the bed, she could see the slimy ocean. That night, the cat didn’t sleep; it growled until morning.

But she did sleep.

It was five o’clock when she woke; outside, the darkness was tinged with light. Had she woken in the morning or the afternoon? She wasn’t sure. How long had she slept? In any case, the inevitable had happened: a slug was crawling on her bed. The time had come. She picked it up by its tail, opened her mouth, and swallowed it. She congratulated herself on having slept so well the previous night: she still had a lot of work ahead of her. ![]()

Valeria Tentoni, born in Bahía Blanca, Argentina, in 1985, is a writer and journalist. She is the author of several poetry books, including Antitierra, Piedras preciosas, and Hologramas. She is also the author of children’s books, such as Viaje al fondo del río, and two short story collections: El sistema del silencio and Furia diamante. In 2022 she won the first Marta Brunet Latin American Short Story Contest in Chile.

Christina MacSweeney is an award-winning translator who has worked with such authors as Valeria Luiselli, Daniel Saldaña París, Elvira Navarro, Verónica Gerber Bicecci, Julián Herbert, Jazmina Barrera, and Karla Suárez. She has also contributed to many anthologies of Latin American literature and has published shorter translations, articles, and interviews on a wide variety of platforms.

Dear fellow delinquents,

Because our counselor—Vlad Siren, whose name sounds suspicious to me—asked us to write a bunch of dirgeful crap to be read aloud here in Tophet County Detention about whether we felt ashamed of ourselves, and because Trusty John claimed he suffered from a sudden and severe case of graphospasm (his letter was blank) despite his priapic drawings of genitalia, I’ll make this short letter as insightful and therapeutic as possible. We’re faced once again with the task of having to sit alone under the pressures of confession and guilt and give the staff insight into our thoughts and motivations, no matter how strange or selfish, so that they know where to refer us for long-term treatment, if we even need it, and to help us understand ourselves better with a goal of rehabilitation and self-forgiveness and a whole-hearted freedom from shame, with the primary, predictable, and asinine icebreaker being: What’s a memory of feeling ashamed?

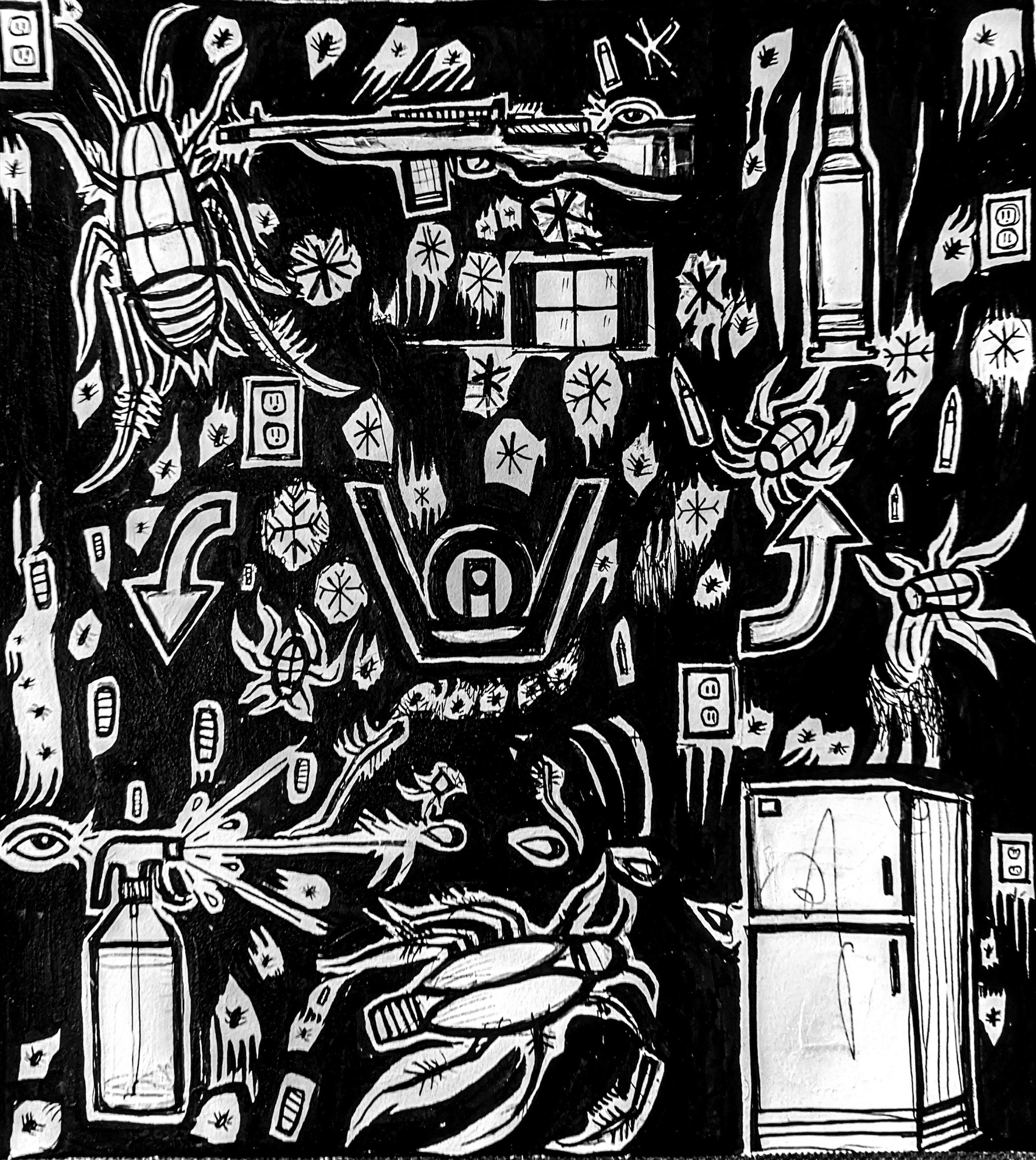

A few years ago, I drove myself to the most horrific visions: I began seeing dying birds. Hallucinations like this, when a room would fill with birds who fell to the floor and twitched in suffering as if they’d been shot, only confirmed the ancient certainty that the strongest feelings of envy, jealousy, and especially anxiety exist within ourselves, in our minds and hearts, and that the people we admire and envy most are the very people who create the fear that lives and breathes inside us. Anytime there was an open window, I would see birds sweep into the room and fall to a slow death. I saw cardinals, blue jays, sparrows, grackles. I saw crows and finches. I saw colorful island birds, twitching, trembling, their wings and necks broken, calling out for help. The visions started sporadically but grew more abstract and detailed the older I got. I saw frogs, hundreds of them, gathering in a room among the dying birds and croaking to their own deaths. Frogs with protruding violet tongues, blinking slowly in the light until their eyes closed and they stopped breathing. I would rush out of the room and tell my dad or mom, who escorted me back to show me there was nothing there, such a sly and evil gesture, playing tricks on me, threatening me with the consequences of demonic possession if I continued to watch horror movies on cable TV, and yet they returned to the living room to sip wine and watch their own movies with nudity and strong language. On occasion I would storm out of the back door while spitting the froth from my stomach bile and stare into the glaucous glow of moonlight and see another frog or dying bird twitching, trembling, suppurating a yellowish custard from their eyes, and because we lived near a river, this fool feared the frogs were arriving from the sleech to seek shelter in our house. They appeared in my dreams, parading in from coastal villages while I heard my father shouting at my mom from another room, several of them crawling into my bed only to die at my feet or on my legs like a wet, heavy blanket. My parents started taking me seriously when I woke them with my screams and they found me cornered in my bedroom at four in the morning breathing the same air as them yet feeling asphyxiated and coughing, kicking at the dead birds and frogs surrounding me. I left a trail of crumbled crackers from the pantry that led from my room all the way out the front door and into the street. For a while I could not find a moment of rest, worried these creatures were invading our home and me specifically for no other reason than mere torture. My parents worried I needed to find a hobby, so my father forced me to watch baseball with him, collect baseball cards, and listen to sports radio. We played dominoes, chess, checkers, and board games for many nights in a row. “Learn to be great at something,” my father said. Like so many other children I was told, after all, that I could grow up to be whatever I wanted to be, no matter what the circumstances, and that as long as I worked hard my dreams would come true; it was the American Dream, my father continually told me. Work hard and you find success. You can be anything you want. Hard work builds character. I was certain, even at that young age, that I wanted to be famous, and my parents took it seriously enough that my mom often accompanied me to the public library and let me pick out art books. I was particularly drawn to surrealism—Salvador Dalí, Frida Kahlo, Leonora Carrington, Joan Miró. At night I studied their work, emulated it, and wrote stories to accompany the drawings. My first story I ever wrote, age six, was titled “The Sad Roach,” about a roach who wants to be a bird so he can fly but instead drowns in a pot of stew. The more I painted, and the more I wrote, the more I felt at ease, less anxious, and happier. I eventually learned to dismiss the visions of dying birds and frogs, even though they continued, because I knew I was safe and they were harmless, but I still kept my guard up anytime I saw them near my bed at night or twitching in my closet. My parents, in strong denial of any mental illness, dismissed these delusions as hyper imagination and encouraged me to use that anxiety and energy toward my art.

Around this time, I first experienced the panic. It was something that led to great shame, mostly due to my own puerile nescience as my father lay drunk in bed after his brother’s funeral while the rest of the guests mingled quietly in the living room with my mother. I found him mumbling something as he rolled over in bed and hung one arm off the side, which was the first time I had seen him that drunk. I sensed the struggle in his body and dizzying mind, heard his throaty cough and groan, and thought the best thing to do was to help my mother with the guests in the living room, but as soon as I entered, everyone stopped talking and looked up at me at the same time. To say this moment was terrifying is an understatement, because all the sudden attention on me felt like I was suffocating, or having a heart attack and needed to vomit. I was certain everyone was staring at me because I had disappointed my family, the dark sheep if you will, always getting in trouble at school and at church, and somehow I felt responsible for my father’s drunkenness that day and felt like everyone knew it.

While the burning pain hit my chest, I was able to retrieve my inhaler from my blazer pocket and take two quick pumps before losing my breath, thankfully, but it didn’t help. The cads who gambled and drank in secret with my father lurched toward me just as I blacked out and fell forward on the hardwood floor, bloodying my nose and cheek. I woke on my back to them breathing down on me with pimento cheese breath, their jowls sagging and cold hands on my jaw and forehead. “Breathe,” they told me. “Are you OK? Breathe.”

The panic attacks continued after that, and every one of them grew worse, so that soon enough I wasn’t able to walk into a room with more than three people in it, which is one of the reasons they put me in the alternative school in North Creek. Try getting dizzy anytime a group of people look at you, or vomiting in church or at the mall. Sixth-grade graduation gave me the stomach cramps, but my father blamed it on the Frito chili pie and Kool-Aid I’d had for supper. I won’t tell you how strong my antianxiety pills are, but it took three different times for me to black out before my father agreed to get me put on meds.

My father is a nondenominational pastor with a love for baseball. He played high school and junior college baseball and had high hopes for me to be a great baseball player, possibly the best since southpaw pitcher George Little Bird, who had made our town proud. I’m aware most of you know who George Little Bird is. His son is here locked up with the rest of us. I wasn’t a pitcher, but my father taught me how to throw a curveball and a fastball. He helped me lift weights in the garage and took me to the park down the street to throw baseballs at the backstop. I wanted to be a catcher, like Johnny Bench, but he insisted I try out for pitcher and stood on the mound with me every Saturday and after church on Sundays and some days after school, even in winter, showing me a good windup and form and reminding me of what I kept doing wrong. He would stand with his hands on his knees beside me as I pitched, his face swollen and pink from coughing his lungs out (he was a closet smoker but a heavy one, at least one or two packs every day), trying to distract me on purpose by making grunting noises during my windup because he said his distractions would help me block out other distractions, like crowds during games, which ultimately would make me a better pitcher. He made sure I threw with my right hand always, even though I’m technically left-handed. I’ve been ambidextrous thanks to him, able to write with either hand, bat left and right, and throw the ball especially hard with my right.

However, I had no interest in being a pitcher. On that cloudy day in the last light of a late afternoon winter, when I finally admitted this to him and said, “I don’t want to be a pitcher and I don’t even like baseball anymore,” my father kicked the dirt and sent me to the car, where I sat in the backseat and stared out the window while he lit a cigarette and collected the baseballs. His silence in the car on the drive home was expected, but when I was in bed that night in the darkness and my bedroom door opened and he entered, a tall, towering presence standing in the light from the hallway, he said he was grossly disappointed in me and saddened by my decision not to play baseball, and that there was no use going to the park anymore, what was the point, and that it had all been a goddamn waste of time, which on one hand pleased me but on the other hand his words “I’m grossly disappointed in you” ran through my head all night and for several days afterward, a moment that I would think about every night in bed for weeks, even months, and sometimes I thought about it at the dinner table when my father stabbed his meat with a look of weariness and regret instead of satisfaction and happiness. He was a man who kept to himself at the table, even at restaurants, rarely looking up from his plate, never conversing with my mother and certainly never with me, belching into his fist, staring watery-eyed at his food and chewing with a slow orgasmic intensity that appeared almost theatrical. I watched him eat this way for years. How is eating such a dead and lonely experience? After I told him I didn’t want to play baseball, he used his silence to dismiss me, not speaking to me for days. Even weeks. This was only a few years ago. When he finally spoke to me, he told me he didn’t care whether or not I chose to be left-handed. “The devil is a southpaw,” he told me. “He wants you to rebel against my wishes.”

I didn’t say anything for a while, and in the silence tried to figure out why he believed that. But I felt ashamed of myself, for not loving baseball, for not respecting him, and for disappointing him. My head felt dizzy every time I was around him after that, and I grew angrier and more hurt. I’m not worth much, I guess. I’m not trying to gain your sympathy, but right now I like this place better than I like living at home.

I’ll end by saying that even though many of you delinquents have done terrible things, I have done nothing that wasn’t in the name of justice, an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, and in fact all my good deeds would be way easier to list here than talking about my early memories of shame. For instance, I have tried to understand what it means to love and to be in love with someone, that loving a dog is no different from loving a person, and that with love comes obedience and discipline, which is to be learned if we are to love. Our elderly neighbors once owned a yellow dog. While they were at church on Sunday mornings, I would sneak into their yard and feed the dog, whose name was Honey, and she was a dog who loved honey, crackers, slices of bologna, and even plain bread, which I would keep in my coat pocket for her. Honey appreciated my gifts but growled at me sometimes, and I tried to teach her the importance of trust and affection in a private way without the elderly neighbors finding out.

Understand: soon enough, Honey accepted me, so do not ever say I’m not an empathetic, loving person the way I have loved animals, especially Honey (and later other dogs in my neighborhood), because I love those animals, I really do, I love them deeply, the way the python loves the pig under the deep red moon. ![]()

Brandon Hobson’s most recent novel is The Removed. He is the recipient of a 2022 Guggenheim Fellowship, and his novel Where the Dead Sit Talking was a finalist for the National Book Award, winner of the Reading the West Award, and longlisted for the Dublin Literary Award, among other distinctions. His short stories have won a Pushcart Prize and have appeared in The Best American Short Stories, McSweeney’s, Conjunctions, NOON, and elsewhere. He teaches creative writing at New Mexico State University and at the Institute of American Indian Arts, and he is the editor in chief of Puerto del Sol. He is an enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation tribe of Oklahoma.

“Letter to Residents” is an excerpt from a novel-in-progress.

Illustration: Josh Burwell

Cat got out last week, the gray one with the orange and brown spots, the one I found in the alley behind my apartment a few years ago, the one I lured inside with the rest of my turkey sandwich, I’d gone out to eat a sandwich in the park and I couldn’t finish it, I wasn’t hungry but I’d wanted to eat because it was something to do, and on the way home I took the alleyways like I usually do and there she was, but last week she got out, slipped past me when I was coming in with the mail, and it wasn’t my mail, it was Bill and Judy’s mail, I always bring up their mail with mine but that day I didn’t have any, it was only an electricity bill for Judy and a phone bill for Bill, they’re an old couple and they live above me and they fight all the time but I don’t worry about them, they’re better off than I am, they have each other, I don’t have anyone, I had the cat but she slipped right past me, out the door and down the metal stairs and now she’s gone.

So many verbs in the following sentence. I’m in the kitchen, thinking about the cat, putting the kettle on for coffee, waiting for the water to boil, walking down the hall, sitting at the desk, writing the story.

The thing is I wanted to meet some people, people like me, people who like to read, I guess that’s all I like to do, and I tried a book club at my local bookstore but I’m not any good at discussing books. I used to talk about novels on the phone with my father, in fact literature was the only thing we discussed on the phone, but after we read Madame Bovary two summers ago his eyesight began to deteriorate and his new prescription gives him a headache whenever he tries to read, that’s what he said, so he mostly just looks at the television and I don’t know if I believe any of this about his eyes because when he hands the phone to my mother I no longer hear the TV in the background, he’s either turned it off or muted it, and I can almost hear the sound of pages turning, because he’s sitting there right next to her in bed, and they’re not newspaper pages he’s turning, but the pages of books, of novels, if you listen closely you can tell the difference, and whenever I ask my mother what my father is reading, she puts her old fingers over the receiver, and I hear her panicked, muffled whisper and the volume of the TV goes up, louder than it’d been before, so loud I can hardly hear her when she says, “Reading? Your father isn’t reading. It hurts his eyes to read,” and so I don’t call very often anymore.

It was December when I went to the book club, and it was only a group of old ladies whose husbands had died or who didn’t talk to them or look at them anymore. We sat in a circle on the patio and the propane heaters pumped out enough heat to remind us that we were cold but not enough heat to keep us warm and they discussed Middlemarch and many of them probably wondered why I was there because I didn’t say a word because, like I said, I’m not any good at discussing books and because I have never read Middlemarch.

I was there to see if I would enjoy the book club or if I would enjoy meeting people who like to read and I did not enjoy the book club and the people who liked to read were old ladies and we did not have a lot in common, I’ve never had a husband who died or who wouldn’t talk to me or look at me anymore, but they invited me to lunch after the book club, and one of the old ladies, Linda was her name, paid for my french onion soup and when everyone else stood up to leave the table I stayed behind and drank the rest of my coffee and Linda stayed with me.

“Petracelli. Linda Petracelli.” She held out her hand.

I shook her hand and then put my hands back where they’d been on my lap and then used them once again to lift the cup of coffee to my lips. After swallowing the rest of the coffee I said, “Italian. That’s an Italian name. I read a book earlier this year by Primo Levi.”

“It was called Earlier This Year? I haven’t heard of that one.”

“No, no. It was a memoir, he was in Auschwitz, and I read the book earlier this year. You made me think of it because he was Italian.”

“He was Jewish.”

“Italian and Jewish. You can be both.”

“Well I’m not. Not both. I’m not even Italian.”

“Petracelli?”

“My husband’s name. When he died I kept it. Why would I change it? Back to Smint? Anyway, who cares what my last name is or was. I certainly don’t.”

“Linda Smint?”

“That’s me. Was me. When I was a kid, a girl, growing up. Until I met Peter.”

“Peter Petracelli?”

“Good name right? Why I married him.”

I nodded—and this is the only time I’ll nod in this entire story, others may nod, but not me—and looked around at the other tables. Every table had a muffin on it and none of the muffins looked the same but I won’t describe the muffins anymore other than by saying that they were muffins.

“I’m kidding,” she said. “I married him because he had a big pecker! Peter Petracelli with the Big Pecker! Kidding again. I married him because I liked him. So what’d you think of the book?”

“It was about Auschwitz. It was sad. I liked it but it was sad. It was difficult to read,” I said. “Actually, it wasn’t difficult to read. I’m only saying that because I think I’m supposed to. It read like a page-turner. When bad things happen to people in books it’s interesting.”

“No, Middlemarch. The book we just talked about for an hour. The reason we’re sitting here right now. You didn’t say a word in that thing.” Linda pointed her thumb over her shoulder, as if right there behind her was the bookstore patio where we’d just sat for an hour and not a preteen picking muffin out of his braces.

“Oh, right. I didn’t read it. Have never read it. I was just trying to get out of the house. The apartment. What’d you think of it? You said you liked it. You said you liked a lot about it but that you thought she could’ve used an editor.”

“I said I thought he could’ve used an editor.”

“But George Eliot—”

“I know who George Eliot is. Was. I know who she was. But they don’t. No one corrected me. When I said ‘he.’”

“Maybe they didn’t want you to feel stupid. Maybe they knew and they didn’t want you to feel stupid. Or they thought you misspoke. They were giving you the benefit of the doubt.”

“Maybe.”

“But what’d you think of the book? Off the record.”

“I haven’t read it either,” she said.

Linda Petracelli drove me home and that was the last time I saw her. I should have seen her again—I liked talking to her and I think she liked talking to me—but I never did. I did use her last name in a short story I wrote about a year after meeting her. Smint, not Petracelli. Petracelli has too much of a ring to it. You can’t put a name like Petracelli in a story, it’s distracting. On the way home it occurred to me that she’d never asked me what my name was and that I’d never bothered to tell her. And I don’t know why I asked her to drive me home that day. My car was parked in front of the bookstore and I lived two miles away from the bookstore so the next day I had to walk two miles to retrieve my car. I don’t like how I used “car” and “bookstore” and “two miles” each twice in the previous sentence but I don’t dislike it enough to spend the time reworking the sentence, and I’ve now used “sentence” three times in this sentence (now four times), which is also an issue but one I won’t correct. I guess I liked being in the car with her, I guess that’s why I let her drive me home. I guess a lot.

I started writing stories about a month after I went to the book club. I’d joined “social media”—a euphemism for all of the apps I don’t want to put in my story, a euphemism that is somehow as offensive to me as the names of the apps themselves—looking to find others who cared about the books I cared about, and I found many of them, but none of them simply cared about books, they wanted to write them too. This seemed naive to me. I watch baseball but I don’t have any notion of becoming a professional baseball player and I like to eat a good meal but I don’t plan on opening a restaurant. Why couldn’t they just enjoy the books without attempting to write their own sorry knockoffs? Why was it always this way? But maybe it wasn’t such a bad thing to want to create. It was probably a good impulse and I was probably just in a bad mood. Probably, probably, probably. But I noticed that the people I gravitated toward, who read similarly to me, they always wanted to know what I was working on and if I had any writing published, online or in print, that they could read, and when I said no, I wasn’t a writer, only an enthusiastic reader, our conversations tapered off and I rarely heard from them again. It seemed the only thing left for me to do was to write.

I’d noticed that these people, the ones I’d interacted with, had a habit of sharing their stories with each other before they were published. Many times I’d been asked if I’d like to trade stories with these people. They emailed their writing to each other, asking for general feedback and line edits, but of course all they wanted was to be told that their story was brilliant and there wasn’t anything to be done to it, it was perfect as is and would surely be published. If you gave harsh criticism you’d be excommunicated or ignored and then you’d be alone, surrounded by the books you didn’t actually like to read and with no one to motivate you to write the books you so desperately wanted to write.

And it was around this time that someone I’d met online, a guy named Frank Giblin, who’d self-published a couple novels and hadn’t been satisfied with the experience—he wanted the real thing, he wanted someone else to publish him—posted about wanting to have a space to share his writing with others. A handful replied to his post expressing a similar desire and so they decided to create an online writing workshop that met, virtually, once a week. By this point, many of these people had lost interest in me, they’d unfollowed my accounts, it was clear I wasn’t a writer, and I’d stopped contributing to their feeds by sharing the book covers of the books I’d been reading, and screenshots of quotable passages, and what I thought of said books. It felt like my last chance.

I didn’t have anything to say, I wasn’t particularly upset about anything in my life, other than the fact that I was bored and alone, and I didn’t know how to write a story about being bored and alone. I loved my cat but I was beginning to realize she wasn’t enough for me, she had beautiful green eyes and she was always at the door when I came home from work but our conversations were one-sided and it was time I heard from someone, or multiple someones, on the other side of the conversation. So I sent a message to Frank Giblin. I asked him if there was any room left in the workshop, lied and told him I had a story I’d been working on for months and just couldn’t figure out how to end it, I was never any good at endings. He said of course there was room for me and that I’d make the group an even eight.

And since I’ve joined I’ve had a handful of stories published in some pretty good places, nowhere anyone actually reads, but respectable places, places I can tell people I’ve been published in and they’ll nod and say, “Oh, I love that publication,” which only means they’ve heard of it, and every few months I get a check in the mail for a story I don’t remember writing and it makes me feel good about myself. Sure, it’s not enough to live off of but I don’t need the money. I have a day job that I can’t write about because one day my managers caught me writing one of these stories—I didn’t know they were behind me, they move so quietly, and always together, and they stood behind me watching me type away at the thing, it was only when one of them leaned in to try and read over my shoulder that I noticed them—and the next day I came in to work and there was a form they wanted me to sign, on my desk, right on top of the keyboard, something about how I must not, under any circumstances, write about the company. I signed it and gave it to them but at the end of the day, I’ll write about what I want to write about, because what are they going to do? I’ll say it was all fiction, I’m a short story writer after all. Some other time I’ll tell the story of my coworker, Edward, and our furtive friendship, and how he was goddamned unjustly laid off because they caught him multiple times reading paperbacks at his desk, while on the clock, and they searched the desk and found more paperbacks, which led them to believe he’d been reading at his desk, on the clock, for years, and how he had to move back in with his aging, widowed mother and get a job brodarting books at the local library. It is a moving and tender story.

In the meantime, I get the ideas for my stories from reading other people’s stories in the online workshops. It’s not the same as picking up a published book for inspiration, it’s better, because no one is quite done with what they’re writing and they haven’t shown it to hardly anyone, but the ideas are there and every once in a while you get a line or two that’s perfect. Sometimes all it takes is a strong opening line and then it’s go, go, go, run with it, stamp my name on it and send it out, it’s mine now, finders keepers. And usually, by the time the story is published—if it’s published—the person I stole from has forgotten their beautiful sentence, they’ve forgotten their unforgettable premise, and they’re happy for me, and in a way, they’re happy for themselves, because they were in a workshop with me, and now my story is being published in a physical magazine, and they think they played a part in my acceptance by encouraging me to keep working on the story and to move that paragraph over there and add an extra beat at the end and tweak that sentence here, but they don’t remember what I took from them, they’ve forgotten about their story, the one that’s gone unpublished, the one that will never be published because mine has been published, and if theirs were to be published now, it’d look like they’d stolen from me. I’ve gotten emails, I’ve received physical letters in the mail from these people, congratulating me on my acceptance, and oh how wonderful it will be to see the story in its final form, in print, oh how they can’t wait to hold the magazine in their hands. I pity these people, I do. And I’m grateful for them. Take Greg—he’s a mechanic, he gets up early and climbs underneath all kinds of machinery and fixes things and he comes home from work in the afternoon and washes the grease off of his hands and he writes. He writes stories about the things he fixes and about the guys he works with and it’s better than anything I can do. He logs on to these online workshops and he says hello and he’s got an accent—I think he’s from North Carolina—and everybody loves him and wants to hear what he has to say and I love him too, I want to hear what he has to say. I love his accent and I love his story from last week about Chuck the mechanic who spills coffee on the book he’s reading while on his lunch break and how he puts the book on the hood of a jet-black 1991 Chevy Silverado that’s waiting on a repair. The Silverado’s been sitting in the sun all day and it’s so hot that the coffee dries up in just a few minutes but then the dust jacket of the book sticks to the hood of the car and Chuck doesn’t want to ruin the book, any more than it’s already been ruined, by tearing it off the hood because it’s a first edition of The Wild Palms by William Faulkner—I haven’t read that one, haven’t read any Faulkner, so I don’t know the significance of it being that particular book, and while we’re at it, I don’t know the significance of the truck being a 1991 Chevy Silverado, but that’s not the point of the story as far as I can tell—and it was Chuck’s father’s favorite book and this was his father’s copy, and his father recently passed away and Chuck is reading the book because he’s trying to get closer to his father, even though his father is gone and even though Chuck doesn’t like to read, so when the owner of the truck comes by to pick it up, Chuck offers to buy the truck from him for a flat five grand. The owner is so sick of the way the truck keeps breaking down on him when he needs it most, the last time it broke down he was miles away from a gas station and his pregnant girlfriend started having contractions, so he says, “Sure, you’ve got yourself a deal. It’s about time I got rid of that cursed thing,” and the story ends with Chuck at the bank, withdrawing the five thousand dollars in cash and thinking about how it’s the most expensive book he’s ever bought and maybe the only book he’s ever bought and how the hell is he going to get it off the hood of the truck. Greg’s story is called “The Wild Palms” and the one I’m working on doesn’t have a title yet. I can’t share it with the workshop on Monday because they’ll know exactly where it came from. I’ve got to give it at least a couple months, these things take time, and once I feel it’s done, as done as I can get it, I’ll send it out to some places. It’s about a guy named Stanley who repairs refrigerators. He’s a devout Christian and he carries around his great-grandfather’s Bible in the back pocket of his Levi’s wherever he goes. There are a couple of Christians in the workshop and they seem to be doing pretty well in terms of publications, better than me, and one of them—Devin—had a novel come out last year and people are excited about it, they’re still talking about it, and he’s got this great web presence, sort of a combination bodybuilder-minister thing going on and every Sunday he posts a video of himself doing pushups with a stack of Bibles on his shirtless back while he recites the Nicene Creed. The other Christian in the workshop—Grace—she’s from a small town in Canada and she’s soft-spoken, what I imagine an angel must sound like if an angel must sound like anything, and I can’t quite put my finger on what’s so special about her but there’s definitely something there, she’s mysterious and guarded, severe and playful at the same time, and she’s articulate, more articulate than I’ll ever be, maybe that’s what it is, she’s one of the only people in the workshop who gives real feedback and I guess people don’t mind hearing her criticisms because she makes it sound like she really cares about everyone’s stories, and maybe she does, and anyway, according to her, she was this close to going into a convent before she met Devin and fell in love with his brain and his biceps. I don’t know if they really believe in God or in Jesus Christ, and what the hell, Christianity looks good on those two and what they do on Sunday is none of my business, for some reason my business these days is writing short stories, and if putting a Bible in one of my stories will help it to get published, then so be it. If I’ve learned anything in these workshops, it’s that if you somehow include, in the story you’re writing, the names of authors and titles of books that have inspired you, readers will, often unconsciously, begin to conflate your fiction with the fiction of the authors you’re attempting to emulate. I did it earlier with Primo Levi, when I was talking with Linda Petracelli, I stuck him in there. I did it with George Eliot too, but it’s true I’ve never read Middlemarch, never read anything by her. Greg did it with Faulkner in his story. And, in a way, I’m doing it right now by letting you know that I’m typing this on Stephen Dixon’s typewriter. Do you know who Stephen Dixon is? He published thirty-five books of fiction in his lifetime and he didn’t use a computer when he wrote, only this typewriter I’m typing on right now. He died a couple of years ago but before he died, I wrote him letters because I liked his work and felt he was underappreciated and he wrote back to me, and we had a back and forth like that for a while. He was the last friend I had and after he died, when his daughters were cleaning out his house, they found the letters I’d written him and they wrote to me and asked if I’d like to have his typewriter, and of course I said yes, yes I wanted his typewriter, not to use it, just to have it. I’d been in a bad mood for weeks before I got that letter. I’d gone to the corner store to buy the newspaper with his obituary in it and inside the store I had to dig through the papers to find the right paper and while I was digging a man with a beard and a bald, freckled head said, “Excuse me?” And I kept flipping through the papers, looking for my friend’s name or his face, and I said, “Yes?” without looking up and the bald man said, “Look at the sign.” I stopped flipping through the papers and looked at the man. He was pointing at a sign above the papers. BUY BEFORE YOU READ. I said, “Oh, I’m not reading. I’m looking for an article. I want to make sure I buy the paper that has the article I’m looking for.” He sighed and gave me a look like, Okay, buddy, yeah, sure. “Look at the sign,” he said. “If you’re going to read the papers, you need to buy them first.” I said, “Look, I didn’t want to get into it but my friend died and I’m trying to find the paper that has his obituary in it, okay? Is that okay? Or do I need to buy all of these papers, bring them home, and look through them there?” I thought he’d let up but he didn’t. “I’m just saying, we have that sign there for a reason.” “You’re one of the most bald-headed people I’ve ever met,” I said. “What? Bald-headed?” he said. “And later tonight, after you’ve closed and gone home and you think the worst part of your day is done, I’m gonna throw a brick through this goddamned plate-glass window, I swear to God.” I threw the papers back on the rack and he shouted, “Don’t come back,” and as I was walking home I thought about how it probably wasn’t a good idea to threaten my corner market and how I have nothing against bald-headed people, one day I’ll be bald if my mother’s father’s head is any indication, and now I wouldn’t be able to shop there when I needed a can of crushed tomatoes or a lemon or lime or a newspaper with a friend’s obituary in it and I’d have to walk about a mile to a different grocery store where there was only one cashier and the line was a mile long and everyone hated everyone else for buying groceries and being in each other’s way, but the good news was I never saw the bald-headed man ever again because the corner market went out of business a few weeks after our altercation and it was replaced by a new market where college students worked the registers while listening to their headphones and it’s great because they let you look through the papers before you buy them and they don’t say anything to you when you’re checking out, they don’t even tell you how much you owe them, you just give them your card and they give it back to you with a receipt, and you can kind of disappear for a while when you’re in there. But I was telling you about Stanley. Do you remember Stanley? He’s the refrigerator repairman in the short story I’m working on. So, one day Stanley’s in somebody’s apartment fixing a leaky refrigerator and he bends over and his great-grandfather’s Bible pops right out of the back pocket of his jeans and lands in a puddle that’s formed around the refrigerator. Stanley’s quick and the first thing he thinks to do is to put the heirloom Bible in the freezer of the refrigerator. So that’s what he does, and he slams the freezer door shut and continues working on the refrigerator. And here I had to research refrigerator parts, not a big deal, we’re all a Google search away from knowing how to repair refrigerators. There are four main types of refrigerators: compressor, absorption, Peltier, and magnetic, and I had Stanley working on a faulty expansion valve in a regular old compressor refrigerator. Do you see where I’m going with this? While he’s working on fixing the expansion valve, the leatherbound Bible freezes and sticks to the bottom of the freezer next to an old Popsicle and a half-eaten pint of ice cream. When he’s finished with the repair, he opens the freezer door and there it is, a frozen Bible block. Stanley’s afraid if he tries to break it off the bottom, it’ll crack the frozen book into pieces. So what does he do? He decides to leave the Bible in the freezer and tells the customer he’ll buy her a new fridge if he can take her old one home with him. She doesn’t care about the fridge, she just wants one that’ll keep her desserts cold, she’s had it up to here with this refrigerator, you should’ve seen what it did to her coconut cream pie last week, so she says, “You’ve got yourself a deal. It’s about time I got rid of that cursed thing,” and the story ends with Stanley and the woman in a Sears picking out a new refrigerator. Of course he knows a lot more about refrigerators than she does because refrigerators are his life and he’s trying to tell her which one will give her the most bang for her buck and I’m still deciding whether or not they’re going to get together, maybe he’ll take her out for a slice of coconut cream pie and coffee from his favorite diner, or maybe I’ll just keep it simple and Stanley is strictly business. At this point it doesn’t matter. The clock is ticking. I’ve got to send this one out soon or next thing I know I’ll be congratulating Greg on the publication of “The Wild Palms,” and I’ll be in the magazine section at the Barnes & Noble down the street, struggling, unable to find a copy of the magazine Greg’s story appeared in—I’m not going to read it, I just need to see the damn thing with my own eyes—until a bookseller asks me if I need any help and I’ll say no, well, yes, yes I do need help, do you carry such and such magazine, expecting the bookseller to say no, of course not, we’ve never carried that magazine, but the bookseller will find it almost immediately, somewhere between Harper’s and the New Yorker, how could I have missed it, and when he hands it to me—it’s always young men working in this Barnes & Noble, young men who look like me only they’re wearing name tags—instead of looking at the magazine, I’ll bring it straight to the counter and buy it and take it home with me and read Greg’s story in one sitting in the armchair by the bay windows, wishing the whole time that I’d written it, I should have written it, it should be my name on that story, my name in that magazine, and I’ll close the magazine and stand up and go to my desk and open the bottom drawer where I keep the others, drop it in and close the drawer, and type up an email to Greg, telling him how special it was to see the story in its final form, in print, and I’ll keep the email brief and read it over twice to make sure there aren’t any typos or grammatical errors and then I’ll send it off.

I need to go for a walk. Bill and Judy are fighting above me and Bill’s playing one of his jazz records and I think I like jazz but I don’t like the way it sounds coming through the ceiling, I don’t like the way anything sounds coming through the ceiling, and I know I need to go for a walk. I put a jacket on even though it’s hot in my apartment and probably near as hot outside. I don’t like carrying things in my pants pockets, they fit better in my coat pockets, so I put my wallet in the left coat pocket because I may want to buy an ice-cream cone and I put my phone and keys in the right coat pocket and I leave the apartment. I’m halfway down the street when I realize I forgot to lock the door but it’ll be okay, it’s always been okay, no I’m not going to return to my apartment and find it’s been burglarized, that’d give me something to write about for Monday and I have nothing to write about for Monday. Nothing ever happens to me. Nothing I can write about for Monday. I walk to the park two blocks away. I see a lot of dogs in the park and none of them are dogs I want to pet but when I pass them the owners give me that look, Yes, go ahead, you can pet my dog, even though I’m not interested in petting their dogs, any dogs, but I do. I pet every dog I pass. And I say, “Isn’t she cute,” and the owner says, “It’s a he,” and I say, “Well, isn’t he cute,” and I force a smile and keep on walking until again, “Isn’t he cute,” and, “It’s a she,” and, “Well, isn’t she cute,” and I keep on walking until I climb the stairs that lead out of the park. I take the side streets and alleyways home to avoid other pedestrians and dog owners and dogs. I don’t stop for ice cream. I need to get home. I have to write something to show these people on Monday. I think maybe I’ll see a cat, not my cat, any cat, pop its head out of a dumpster or a trash can—that’s good luck—but I don’t, only garbage. A warm breeze blows a chip bag and it follows me for a few feet before I turn the corner. The last story I wrote had “chip bag” in it and here it is again, it must mean something to me, there must be something I like about the phrase “chip bag.” I should’ve named my cat but I could never decide on a name and then it was too late, she was “cat,” just “cat,” just “my cat.” I’m the same way with my stories. I can never come up with a title I like, one that fits, I usually just pick a word or a line from the story and then if the story gets picked up, the editor changes the title to something else, something that makes sense and doesn’t feel forced. But I should’ve named her, she wasn’t a story. I walk up the steps to my apartment and turn the handle on the door but it won’t turn because it’s locked. So I didn’t forget to lock it. I reach into my left pocket for the keys but they’re not there. They’re in my right pocket. I unlock the door and open it and go inside and it smells like something’s burning. I go into the kitchen and the kettle is on the stove and water is bubbling out from beneath the lid and hissing on the burner and I turn off the stove and move the kettle to a different burner. I go into the living room. Bill and Judy aren’t fighting anymore, at least I can’t hear them, they must’ve gone out or gone to bed, but Bill left his record player on and he didn’t flip the record and the needle skips and skips at the end of the record and it’s about time he got rid of that cursed thing. ![]()

Joseph Grantham is the author of two books of poems. His fiction has appeared in Bennington Review, New York Tyrant, Autre Magazine, and elsewhere. He lives in America.

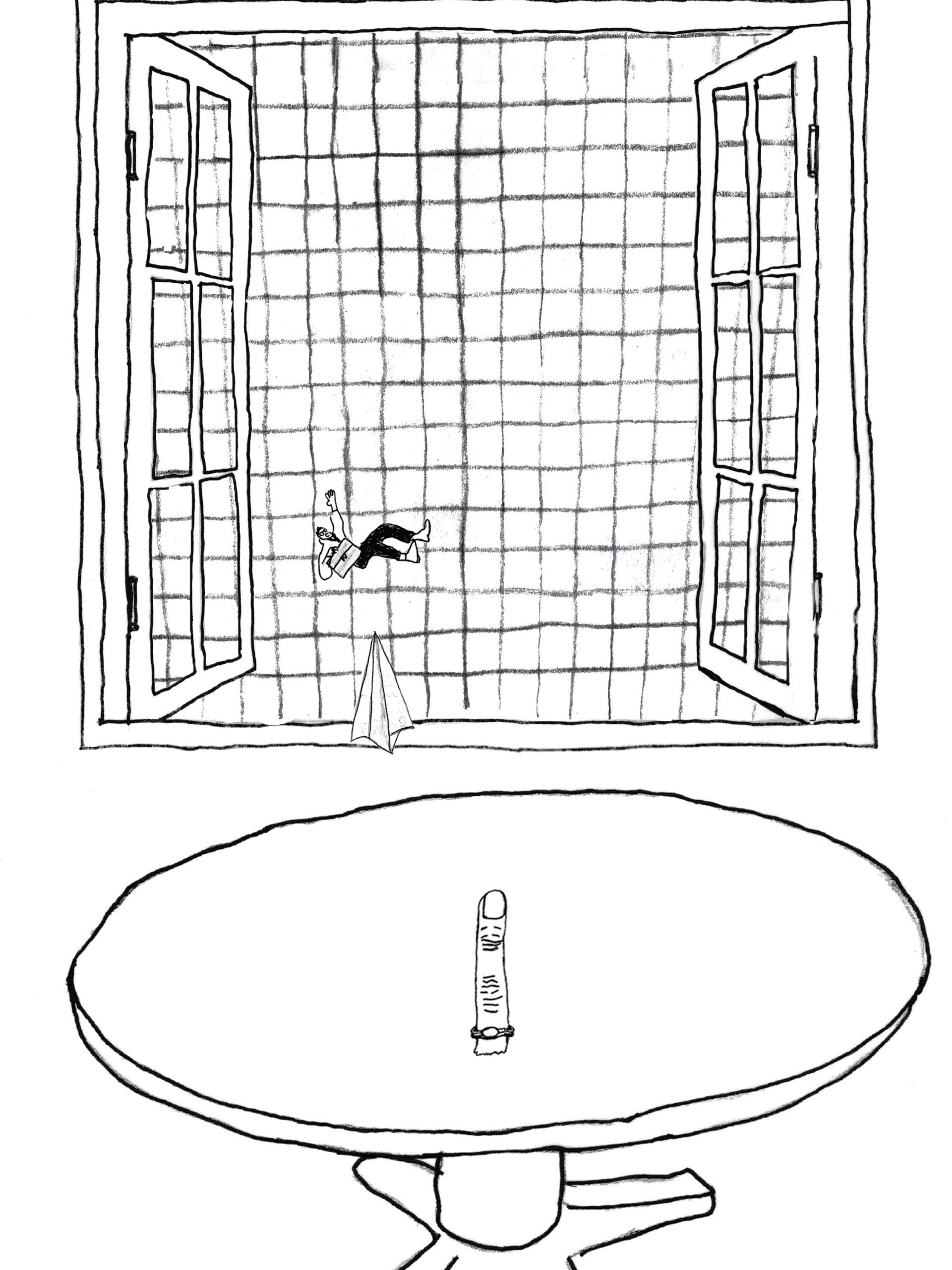

Illustration: Rae Buleri

Thy dead men shall live,

together with my dead body

shall they arise.

Awake and sing, ye that dwell in dust:

for thy dew is as the dew of herbs,

and the earth shall cast out the dead.

—ISAIAH 26:19

On the road to Mar Bravo there’s a cemetery for poor people. It became a pilgrimage site for the chosen ones because four of their own were buried there. Between the graves adorned with artificial flowers faded by the sun, headstones with chipped corners, and weeds, the girls cried with their sparkling skin, their white blouses, their jean shorts, their beaded necklaces, and their strappy sandals. They hugged and patted one another like nymphs before the body of a lamb. Beside them, with dry eyes and their hands clenched in fists by their sides, stood the males of the species: boys with hair falling into their eyes, their arms deliciously hard. Freckled, smooth-skinned, silent, and sullen like geniuses or like idiots, so handsome it was scary.

Among the carpenters, seamstresses, fishermen, and babies malnourished from the womb, they buried the four surfers from Punta Carnero. The parents had decided that their sons should be laid to rest in that gray cemetery and not in the rich people’s one, with a lawn as green as a parrot, fresh roses—red and shameless, brought in by refrigerated truck—and marble headstones with religious inscriptions below the long surnames. They thought that the corpses of the most beautiful drowned men in the world should remain forever beside the sea. There were four of them; they would inherit the earth. The night before their deaths they’d broken a combined total of seventy-seven hearts at the yacht club party, kissing their gorgeous girlfriends and grabbing their little asses through their sundresses. At dawn, still drunk, they sheathed themselves in black neoprene and, only their skulls exposed, went out to brave the rough waves, convinced of their boy-god immortality. The sea spit them out on the seventh day, soft and whitish like newborns.

We always drank there, outside the Mar Bravo cemetery, because what else did we have to do? All the parties were private, by invitation only. Beautiful boys invited beautiful girls, average boys invited beautiful girls, hideous boys invited beautiful girls. Doors that looked like the gates of heaven opened up for other girls—but never for us. One time we tried to get into a party and the bouncer told us that it was for friends only and we answered: “Whose friends?” But the man was already lifting his pretenses of security, the velvet rope the color of blood, for an athletic, angular, smiling girl who looked like someone out of a tampon commercial. We were dying to find out what went on behind those pearly gates, even though we instinctively knew that there was no place for us there, that once inside, our defects would multiply until we choked on them, that we’d become a hyperbole of ourselves, fun-house mirror versions: the fat one, the butch one, the lanky one, the flat one, the hunchback. Just as the pretty girls would become even more attractive together, their collective virtues masking any individual defects to make one another look better until they shone like one giant star, girls like us are an obscene spectacle when assembled, our failings exacerbated into a kind of freak show: we become even more monstrous.

We knew, of course we knew, that not even the most desperate boys, not even those who were overweight, nerdy, or goth, would approach us. The only people who approach girls like us are girls like us. Why even bother? We were free to go anywhere we wanted, and we hated that: We longed for the beautiful girls’ lack of freedom, for the arms of our boyfriends like yokes around our necks, for quickies in the pool house without a condom, for big baseball-player handprints on our asses. We wanted to be taken by force and with every thrust to squeal the beautiful names of those beautiful boys. We wanted to spread our legs for them and grab their perfect hair when we came, knots the color of sand between our fingers. We wanted to make sweet cocktails and witches’ brews from the nectar of their sexes. We wanted the pretty girls to disappear, to slice off their heads with flaming machetes. We wanted to enter those private parties mounted on flying nags to bursts of thunder and shouting and lightning and earthquakes and to rain down on those beautiful idiots a plague of locusts and serpents. We wanted to make the pretty girls kneel before us, powerful Amazon warriors that we were, and for them to watch helplessly as their men climbed, enchanted and docile, onto the backs of our horses. We wanted, we wanted, we wanted. We were pure want.

And pure rage.

The day will come, yes sir, when everyone will notice us and will say to anyone who will listen: Love them. Love them. And that mandate will travel the earth. The day will come when we wipe away each and every one of our tears.

In the meantime, we had a car, we had money, we had the night, and we had nothing.

We would park outside the cemetery with plenty of alcohol, plenty of weed, plenty of pills, and plenty of cigarettes. At least we had that, the means to get fucked up, to sully our bodies with something perverse, to feel like bad girls. Virgins, incredibly obscene. Morbid, lonely. How great it would’ve felt to be desired by one another: to desire our friendly tongues, to reach ecstasy with only our fingers inside each other, to find the tender, juicy flesh and flower between our legs. Being a lover is so different from being a loser. To throw a passing glance at the closed doors of the private parties and feel thankful not to be there, bored, with some idiot’s stiff, wet tongue in our ears or leaving horrible marks on our necks. We should’ve found love among ourselves, but we are who we are and what we are is almost always cruel.