Desolation Row Revisited: Bob Dylan’s Rock Poetry

From the Archives

By Thomas S. Johnson

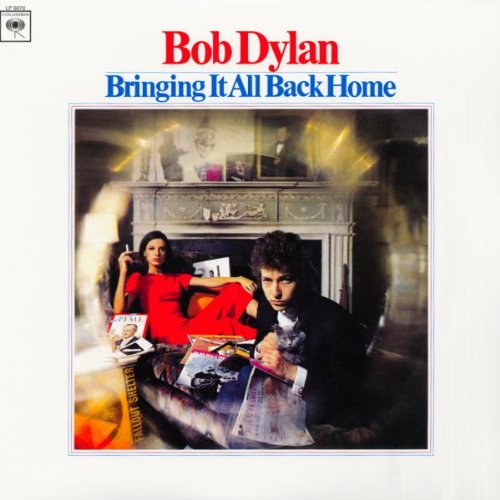

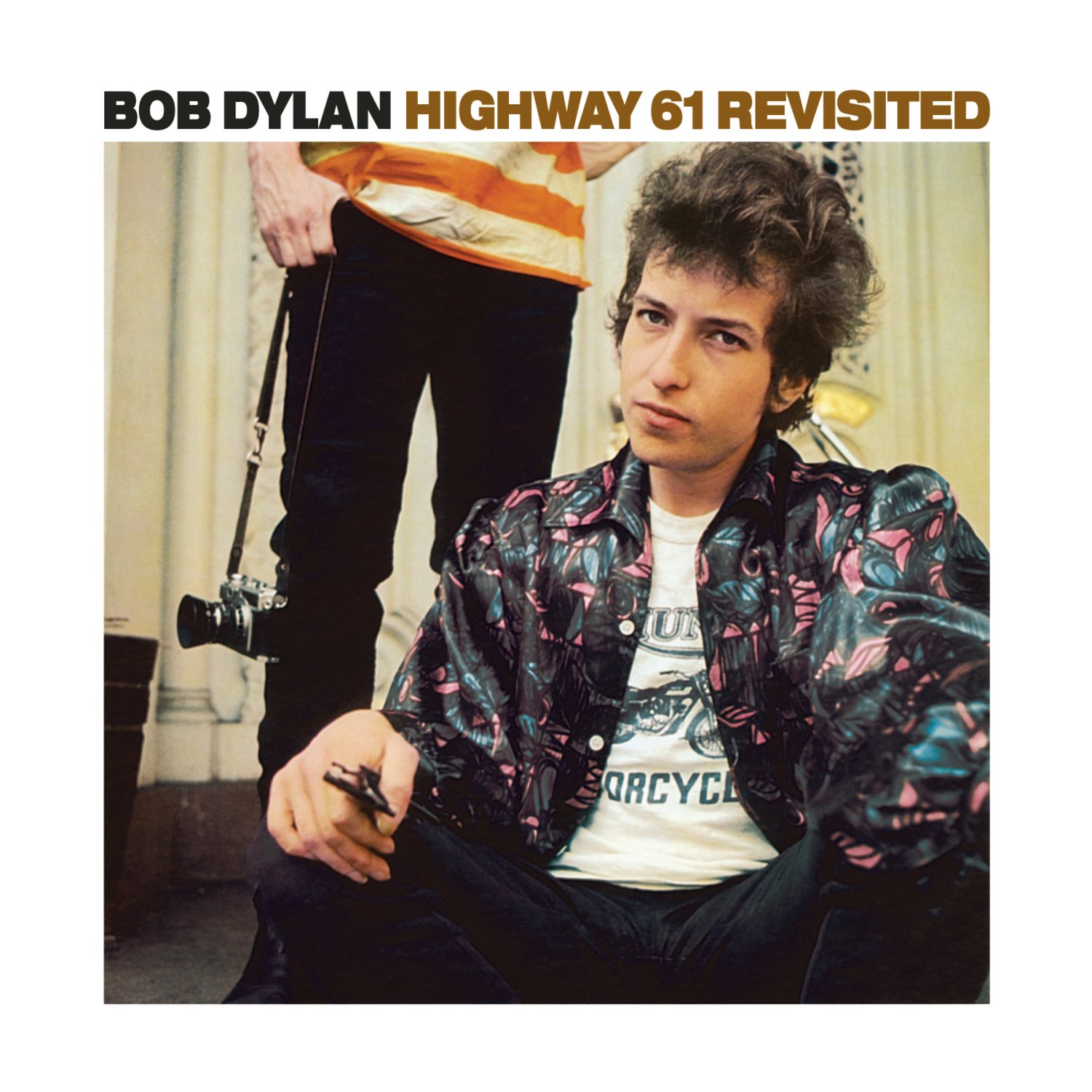

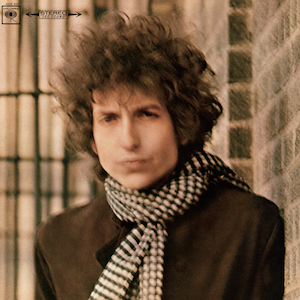

What was Bob Dylan doing when he moved into rock music in midcareer? His first albums were in a folk-protest idiom. His later albums tended to return to a folk-country idiom close to his first albums. But the latter were markedly different because of three central albums that intervened: Bringing It All Back Home; Highway 61, Revisited; and Blonde on Blonde. Perhaps now, knowing where his music went, we can begin to look back and try to understand what were the underlying motives for that excursion. There are certain songs on these three albums that stand out from the rest as highly individualistic even within Dylan’s own canon. They establish a continuity and developing attitude that seems to underlie Dylan’s work in this period, an attitude which proved untenable and which finally forced him out of rock altogether.

The common interpretation of “Mr. Tambourine Man” is that it describes a drug high, the Tambourine Man being the dealer, his song being a hint of the visions he will give the poet through drugs. The imagery of the song would tend to back this up. In the first verse the poet states his readiness to begin to trip out. In the second verse the actual high begins to take effect: the singer’s hands and feet grow numb and “lose their grip,” and he loses his hold on reality. In the third verse he is “laughing, spinning, swinging madly across the sun,” and in the fourth verse he travels down through his mind, seeing the various things buried deep beneath the “waves” of his subconscious. Such specific imagery can be compounded and the song becomes simply the description of a drug high, but this does not explain everything in the lyric. The chorus and first verse, for example, do not mention drugs or use extensive drug imagery. The third verse does not seem to contain explicit drug references. Throughout the song there is imagery referring to music and dancing and singing. In both verse one and verse three another obvious mood is that of wandering, searching. The entire song is operating in the imperative form of the verb: the poet asks the Tambourine Man to play his song, he demands “take me on a trip”—he is ready to go, and in the second verse he promises to go. In the last verse he says “take me disappearing,” and “let me forget about today.” The song ends with the repetition of the chorus, which is quite clearly calling on the Tambourine Man to play him a song, which he will follow, the spell of which he will go under. The plaintive tone in which Dylan sang the song in its original release makes the imperative tone all the more forceful. But the singer himself never has his wish granted. He never joins the Tambourine Man, nor does he ever hear the song fully; he only imitates it in a way he tells the Tambourine Man to ignore, his imitation being aimless, he only a chaser of shadows. This point of view of the singer in relation to the Tambourine Man is the key to the song. The imagery points to the feelings evoked by the singer’s realization of his place and its implications and consequences for him.

The common interpretation of “Mr. Tambourine Man” is that it describes a drug high, the Tambourine Man being the dealer, his song being a hint of the visions he will give the poet through drugs. The imagery of the song would tend to back this up. In the first verse the poet states his readiness to begin to trip out. In the second verse the actual high begins to take effect: the singer’s hands and feet grow numb and “lose their grip,” and he loses his hold on reality. In the third verse he is “laughing, spinning, swinging madly across the sun,” and in the fourth verse he travels down through his mind, seeing the various things buried deep beneath the “waves” of his subconscious. Such specific imagery can be compounded and the song becomes simply the description of a drug high, but this does not explain everything in the lyric. The chorus and first verse, for example, do not mention drugs or use extensive drug imagery. The third verse does not seem to contain explicit drug references. Throughout the song there is imagery referring to music and dancing and singing. In both verse one and verse three another obvious mood is that of wandering, searching. The entire song is operating in the imperative form of the verb: the poet asks the Tambourine Man to play his song, he demands “take me on a trip”—he is ready to go, and in the second verse he promises to go. In the last verse he says “take me disappearing,” and “let me forget about today.” The song ends with the repetition of the chorus, which is quite clearly calling on the Tambourine Man to play him a song, which he will follow, the spell of which he will go under. The plaintive tone in which Dylan sang the song in its original release makes the imperative tone all the more forceful. But the singer himself never has his wish granted. He never joins the Tambourine Man, nor does he ever hear the song fully; he only imitates it in a way he tells the Tambourine Man to ignore, his imitation being aimless, he only a chaser of shadows. This point of view of the singer in relation to the Tambourine Man is the key to the song. The imagery points to the feelings evoked by the singer’s realization of his place and its implications and consequences for him.

Dylan begins the song, and presents his basic attitude, in the chorus. He is awake, waiting for somewhere to go. The first verse specifies his position—“evening’s empire” has turned to sand that has slipped through his fingers, and he is blind, weary, stranded, alone on an empty street “too dead for dreaming.” Evening’s empire is the realm of dreams. He says farther on that he is unable to sleep and cannot dream because the street is too dead, and he is, according to the chorus, waiting for a dawning. The singer is emotionally empty. He cannot “dream,” i.e., create his own visions. These dreams are like sand that has slipped away leaving him trapped on a “dead” street. The old values, idioms, visions are no good, and he needs new ones his past experience cannot provide—he needs the inspiration of the new song, or vision, of the Tambourine Man, which he pleads for in the chorus.

In the second verse he points out his readiness to begin his trip, to fade “into my own parade.” On the one hand this implies fading into his own mind, his own world. He also recognizes that what he needs is an idiom of his own, a “parade” moving down his own road, to replace the dead form he has worked in. Again the chorus, and he calls on the Tambourine Man for inspiration, to help him find his way.

The narrative point of view then shifts from the first person to an ironic second person. The point of view becomes that of the Tambourine Man as the poet conceives of him, and the third verse considers what the Tambourine Man must think of this poet and his songs. The poet is a “ragged clown” rolling off “skipping reels of rime” to the tempo of the tambourine. But his rime is not “aimed at anyone”—it’s simply “escaping on the run.” It is without direction, and if he were the Tambourine Man, he “wouldn’t pay it any mind” because the poet is only capable of chasing shadowy things which the Tambourine Man alone sees clearly. The poet follows the Tambourine Man realizing he will miss the substance of the vision and seem absurd to the Tambourine Man’s objective eye. But he is willing to seem so for the sake of the inspiration he hopes to realize, and he interrupts this line of narrative to make his choric plea again.

The singer then looks into himself to find what he will see, given the inspiration of the Tambourine Man. He wishes to delve into his mind to escape his consciousness and his subconscious fears, the “haunted frightened trees,” the “foggy ruins of time,” and the world he lives in, to realize a fresh elemental vision, represented by the setting of sea, sand, and sky. On the beach, confronting the sea, the primordial element of nature, he would drown memory, time, fate and its consequences, and experience a pure poetic vision (“dance beneath the diamond sky”). Then he would be able to forget about the present and his frozen loneliness until a tomorrow which will never come, since time will have been buried. The dawning of a new vision of the world will resolve his present emptiness. But the chorus interrupts again, and again the plaintive plea is made. He has not been granted the vision and inspiration he has sought. He never goes on the trip with the Tambourine Man.

The poet is on a street “too dead for dreaming.” But with no dreaming there can be no new vision. There is no one on the street to lead him, and so he called on the Tambourine Man to help him. But the Tambourine Man exists in another world and either cannot or will not help him, and the poet on his own cannot make the leap into that world. Thus the cry at the end of the song is a cry of futility. He is left alone, cut off from the world he lives in and the world of the Tambourine Man—as Arnold put it, stranded between two worlds, one dead, the other waiting to be born.

And so what is he to do now? He chooses to take a closer look around, both at the street and at the world just off of the street. The results are not edifying, for the remainder of this album and much of the next detail a catalog of grotesquery and nightmares almost unparalleled in contemporary poetry. A good example of this, and perhaps Dylan’s most powerful single lyric, is “Desolation Row” on the Highway 61, Revisited album. “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues,” preceding “Desolation Row” on that album, presents several motifs he will use later.

The first verse of “Tom Thumb’s Blues” says: “Well you’re lost in the rain in Juarez, and it’s Eastertime too, / And your gravity fails and negativity don’t pull you through. / Don’t put on any airs when you’re down on Rue Morgue Avenue, / They’ve got some hungry women there, and they really make a mess out of you.” It is Easter, and it is raining, two standard symbols of redemption and the rejuvenation of life, but they bring no relief to someone lost in negativity, without energy or inspiration, on a “dead street” (the “ancient empty street too dead for dreaming”) of prostitutes. It is no place for airs, for trappings of superiority. Everyone is equally exposed in a whorehouse.

The song reviews a series of prostitutes, their activities and histories, and the poet’s own life, leaving the listener to come to “Desolation Row” seeing the individual lost in the chaos of a world full of grotesques. Negativity, the refusal to accept any positive values or to capitulate to his situation, is the only power he has, and it’s not enough to survive on. The world for him is stripped of any pleasant accouterments, and naked reality is exposed. With this rather bleak view of things, Dylan shows us the world around his dead and empty street, now called Desolation Row.

In “Desolation Row” Dylan turns his back on drug visions and visionary hopes to face reality as he sees it, and he sees the world in the aspect of a carnival, specifically a freak show, with all the grotesques on prominent display. The lyric tells of the parade of grotesques that pass before the poet, a stream of images generated by a letter full of gossip he has just received from an old acquaintance.

The opening is primarily an impressionistic panoramic overview of the world around his street, setting the scene for the specific and deeper probings to follow. The first three phrases present three spot images, one of them grotesque postcards of a hanged man, reminiscent of the hanged god of The Waste Land, another failed symbol of fertility and redemption. The fourth phrase gives us the setting of the lyric: “The circus is in town.” The blind Commissioner (probably of police) parades by in an autoerotic trance, following a tightrope walker, a man skilled at keeping himself in balance. It is evident he needs this skill, as the Commissioner’s riot squad is restless, and the tightrope walker is seeing that they are not unleashed by controlling the controller of the town. The last line sets up Dylan’s position as the observer of all this, looking out over the activity, and it is his consciousness that will provide the center and ordering point for the chaos to follow.

There are two important women on the Row, Cinderella and Ophelia. Cinderella is a prostitute, confronting Romeo, the idealistic lover, who is told to leave. On this street there is no place for such a ridiculous adolescent. An ambulance carries away the dead Romeo, leaving Cinderella to her perennial task of sweeping up. There will be no Prince Charming here. Ophelia is just the opposite of Cinderella, a professional virgin. Although only twenty-two, she is already an old maid because she has sacrificed love and affection for her career, armored herself, and become one of the iron maidens of modern business. The iron vest she wears is a likely metaphor for the way she has armored her mind and body against love and sexuality.

Science and medicine fare about as well as sentimental love and affection here. Albert Einstein, the symbol of modern science and technology, is presented in the guise of Robin Hood, perhaps representing his symbolic position today as the bringer of the riches (and horrors) of modern living to the everyday man. For Dylan, all he can ultimately do is bum cigarettes, sniff drainpipes, recite the alphabet—absurd activities. Science and technology and all they involve, represented in this man, have become a meaningless and occasionally grotesque parody of humanity. Einstein once played the violin, a creative human expression, but that was long ago, and he escaped humanity in science. Technology offers as false a hope as Ophelia’s rainbow. Einstein is now only a parody of what he once was.

Dr. Filth is a figure I can’t pin down specifically. Since verse six echoes the drug imagery of “Tambourine Man,” he could be a physician who sells prescriptions for drugs. His nurse’s cyanide hold would be the doctor’s own stash from which he sells direct. But in this role he is as useless as anyone else on the Row. The drugs offer no more hope than the rainbows.

There is no hope even in the stars. The third verse, the first “Eliotesque” verse, so called because of allusions to The Waste Land in the figure of the fortune-teller, the mechanical lovemaking, and the motif of waiting for rain, begins with the blacking out of the stars and moon, standard symbols of romance and the aspirations of men. The fortune-teller has given up the ghost and gone inside—there is no fortune to tell without the stars. The only ones left who aren’t waiting for release from their lives are Cain and Abel and the Hunchback of Notre Dame, the first an image of death and hate where there should be love, the second an image of ignorant and deformed love. The Good Samaritan is also dressing for the show—he too is now a freak, to go on display in the modern carnival freak show.

And so the stage is set for the presentation in verse seven of the main show of the carnival. The central figure is Casanova, standard representative of sexual energy, and the occasion is his punishment. His crime? Not his dissolute life, which in its essential sterility is in keeping with modern life, but rather his trip to Desolation Row. Casanova has been to the Row and as a result has lost his assurance, his potency. On Desolation Row he has experienced the nothingness of his life—the end of the road, the absolute nihilism, the knowledge of his irrelevance, which comes when he must face the fact of his own ultimate impotence. The result of this experience is that he must be spoon-fed if his illusions are to be revived and he is to become again one of the carnival’s proper functionaries. He is not being killed and poisoned literally; rather his experience on Desolation Row, where he lost his self-confidence, must be purged by means of false self-confidence and the superficiality of words. This, to Dylan, is as good as death, because the loss of assurance is implicitly the beginning of true insight. Casanova has been dragged off of the Row (“across the street”) to receive his punishment. The difference between the grotesques over there and those on the Row is simply that those on the Row are aware of what they are, where the others are not.

As the show goes on, Dylan widens his focus to include the backdrop for all these activities. The larger world is not pleasant looking. Verse eight is a Kafkaesque verse, with its dominating image of the castles. It is midnight, but instead of witches and werewolves, it is the agents, crew, and insurance men from the castles who sweep down to scour the land (perhaps from Housing Project Hill in “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”). Their prey is anyone who rises above the common lot, anyone who has greater knowledge than they. The exceptional man is saddled with an impossible load which leads to a heart attack, modern business of whatever sort being an environment that will kill superior individuals. If they are not killed by these heart attack machines, they will evidently be burned out; their lives will be sacrificed. The agents also go to seal off Desolation Row. For anyone to be able to escape there and experience its negativity would be a threat to their rule. Realizing the ultimate uselessness of their society, these escapees would become its enemies.

Carnival imagery is now of less importance. The song has expanded in its significance by positing a dark and mysterious power at the center of the world, the castles. What these castles are is not explicit, as was also true in the Kafka novel. The important thing is that they exist out there and threaten all aspects of contemporary life.

One escape route is posited by Dylan, however—the Titanic. In verse nine, the Titanic is to sail at dawn. In “Tambourine Man” dawn and the ship were to bring a new vision. Here they bring death and destruction to one of man’s great creations. From this point on this can be seen as the second “Eliotesque” verse, with specific references to Eliot and Pound and to the calling mermaids of “Prufrock.” The central image again refers to the dissolution of the poet’s idiom or inspiration. One of Dylan’s major influences is the poetry of these two men, but they are doomed without even realizing it, so caught up are they in their own petty arguments. With the sinking of the Titanic comes the death of the meaningfulness of Eliot’s and Pound’s poetic idiom. Fishermen and calypso singers laugh at the two men for their irrelevance to real life. But ironically these figures are themselves irrelevant. They have no answer to give to the doomed men; they only laugh and mock. They live in a world of mermaids by the sea, an enticing solution for Eliot to the problems of his world, but one which he rejected. Here the solution is absurd in the context of the poem. All of these people have ignored, in fact never really recognize, Desolation Row, and therefore are destined to irrelevance forever. This verse is followed by a long harmonica interlude, indicating a break in the process of the poem and a preparation for a new orientation in the last verse.

Dylan finally addresses himself to a person who has just written him. This person has evidently included the usual banalities of personal letters: inquiries as to health, news and gossip of various people, etc. To Dylan, all of this is “quite lame”—he has to rearrange everything to understand what the writer was talking about. The people we have just seen on the Row are his rearrangements of the persons referred to in the letter. And why has he had to do this? He has been to Desolation Row, in fact he is still there, and he has little in common with people who have not experienced the place. For him, the only people who can say anything are those who have the courage to step onto Desolation Row and experience an absolute nihilism.

Since he was forced to give up the dream of the Tambourine Man, Dylan has forced himself to see the place where he stands for what it is, has moved toward the nadir point of his existence where old values, institutions, and aspirations are obliterated or distorted in an absolute negativity. He is surviving. The experience of all this is recounted in “Desolation Row,” and this experience he has resolved into a tremendously powerful lyric. But he is not yet free. The experience has not been weighed, balanced, judged. Indeed it seems as though, given the poet’s detached place in the song, it has not even been fully absorbed yet. It remains to be seen at this point whether he will find any resolution. He takes up this problem in “Visions of Johanna.”

“Visions of Johanna” is probably Dylan’s most difficult lyric, made up of a series of highly personal and shifting images and references. It is also filled with sexual and drug imagery, important vehicles in establishing the theme and motif of the song, the only song on the Blonde on Blonde album that uses this imagery in such concentration and profusion.

The motif of the song is the unstructured stream-of-consciousness thoughts of a young man (the poet) sitting in a room with a girl named Louie and her lover. The basic theme of the lyric would seem to be the poet’s feelings of being abandoned, left alone to face the Visions of Johanna. The definition of these Visions is developed slowly through the poem. They are not the inspiration Dylan has been seeking since “Tambourine Man,” for the world of this song is a bizarre one derived directly from “Desolation Row,” even to the position of the poet in a room above a street of grotesques. They are visions of love prostituted, and of the negation of life and vitality this prostitution implies, all of which contrasts violently with an idealized love the poet recognizes he cannot have. The conflict throughout the lyric between visions of negation and of an idealized love lost and prostituted sets up a tension that leads to the final dissolution of the song. The ideal and the real are irreconcilable, and end by destroying each other.

This duality in “Visions of Johanna” is the result of the combination of two image patterns that have developed in previous songs. The idealized vision of the Tambourine Man, the poet’s vision of an energizing relationship, is now conceived of in terms of a lost love relationship. The visions of the nihilism of life in “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” and “Desolation Row,” also included here, imply the complete breakdown of the poet’s world and by implication of his own mind.

The first verse again sets the scene of the lyric. It is night, and three people are sitting in a loft “stranded,” though they won’t admit it. Heat pipes cough, lights flicker, and a country music station plays softly, but “there’s nothing, really nothing to turn off.” This all conveys the feeling of nothingness and impotence that will dominate the lyric. There is literally nothing going on; they are all static. The handful of rain is a drug image, tempting the young man perhaps to a pleasant narcotic dream existence. It is also a standard literary symbol of redemption and fertility. Evidently it fails in its objectives, as the world it presents is totally grotesque.

Out on the street there are only whores. A night watchman passing by asks himself just who is normal and who is abnormal here. The answer is ambiguous. Louise, through all this, remains quite calm, but makes it clear that the Visions of Johanna, here the visions of idealized love, are not to be found in this place. Looking back at her, the young man sees that her face is ravaged despite her calm, ethereal pose. Ghosts of electricity (heavy jagged wrinkles) “howl” in the bones of her face, and the only reality she recognizes is prostituted love, something the young man is also coming to recognize.

The grotesque situation is developed through the third verse. The final lines of the verse are a blatant outcry about the impossibility of explaining just what the poet feels, an admission that what he is talking about here is more than his relationship with one woman. Where the first three verses could be seen as a tirade against women, Dylan at this point explicitly says that there’s more going on here than he can explain in simple words. He is trying to present what it feels like to live in a situation where love is dead and the world is totally nihilistic, and he is trying to find some way out of the whole situation. The rest of the song expands this theme.

The scene suddenly shifts to a museum, a place where old things are kept, where Infinity, all time (“the foggy ruins of time”), is on trial. The eternal values and verities no longer carry validity, and must be prosecuted and presumably condemned to oblivion. “Salvation” has become only another trial to be endured, and does not lead to any enduring peace or final decision. Even Mona Lisa, popular symbol of artistic and feminine beauty, has the “highway blues,” a reference to “Highway 61, Revisited” in which the highway is a road to disaster and death. She has seen life in this way, and her smile conveys to the poet the fact that she understands this.

In the following lines, a slightly different tenor is developed regarding the museum art pieces. They are frozen, and women can only sneeze in their musty presence. One of the prime displays here is a mule’s head bedecked with jewels and binoculars. The poet comments that all this finery for a jackass, in light of the Visions of Johanna, seems cruel. That such a grotesque display should be made so much of is a cruel perversion of art.

The last verse again returns to the poet himself, waiting for his Madonna (Johanna, the Tambourine Man, some symbol of spiritual beauty and love, some source of regeneration) who has not yet come to him. The cage that corrodes is an ambiguous image. A cage is a standard symbol of the body, but this does not seem sufficient—rather the cage seems to be a broader symbol of the poet’s mind, the room the poet is in, the museum, and the way of life he is trapped in. The important aspect of the image is the connotative, the impression that everything around the poet is corroding, is dissolving, degenerating to nothingness. The images of the girl on the stage, the fiddler, and the fishtruck are presented in a chaotic series of fragments reminiscent of the last lines of The Waste Land. The song has broken down completely in this last section. Many of the images are ambiguous, possibly irrelevant except for their connotations.

The last three lines seem to wrap up the song as his “conscience explodes.” The constant influx of images and emotions, combined with the visions and the music, has created an emotional overload, has shortcircuited his mind and “exploded” it. The rational structures, the logical thought processes, have been overwhelmed by the power of the Visions and have literally wiped out his intellect, leaving him to face the emptiness and perversions of life without any defenses. It is as if he is saying, as Eliot said, that a man can’t take too much reality. In this song Dylan tried to face reality as he saw it, and it blew his mind. What survives are the sounds of the harmonicas playing skeleton keys, a reference both to the look of musical notes on a page and to the musical idiom he has just pushed beyond its limits, and which has corroded or been obliterated for him; the rain, for Dylan an impotent image of redemption (cf. verse one and “Tom Thumb’s Blues”); and the Visions of Johanna, the death of love and the final forceful confrontation with an immersion in total negativity.

With this song, it would seem that Dylan was unable to pull out of the situation he found himself in on Desolation Row and in “Tambourine Man.” He found no saving grace to reinject hope and vitality into his poetry. Negativity (as he saw in “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”) has resulted in a superabundance of grotesqueries, pornography, deviation. There has been no vision, and negativity did not see him through.

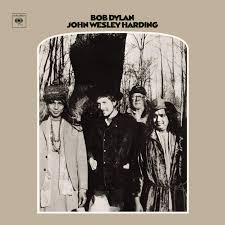

Dylan has sung his rock-song, and there is no Madonna waiting for him. And so he picks up his folk guitar and begins to sing again. The John Wesley Harding album is a reversion to a country-folk idiom, changed significantly because of his experiences through three albums, but still basically a return to a previous idiom. Yet before he steps back into folk music he has a few final remarks to make on it all.

In “All Along the Watchtower,” the I-persona is abandoned for a third person narrative, but the concerns and theme follow directly from the songs I have been considering. It is constructed in three verses that continue one story straight through. The third verse suddenly cuts off the narrative, and the song is left unfinished. I believe this is so because Dylan was reviewing the same conflict he couldn’t resolve previously, and dropped it in favor of his new-old idiom.

The setting and characters have an almost mythic quality. The place is a medieval castle, so distant from our time that it can take on an otherworldly aspect. The two main characters are a joker and a thief, both the disinherited of their society. The joker as a character in, for example, Shakespearean drama, always knew what was going on around him, in fact was frequently the only one who knew this, but was unable to act on his knowledge. He was a character of wisdom, but no potency. In “Tambourine Man” Dylan identified himself with this figure. The joker’s state of knowledge but inability to act was Dylan’s then, and is again.

“‘There must be some way out of there,’ said the joker to the thief. / ‘There’s too much confusion, I can’t get no relief.’” The fragmented world and chaotic life his previous poetry dealt with is too much for him; he can’t support it. None of the common people (plowmen or businessmen) can understand his problem. Wine is a conventional symbol of blood, and the businessmen drinking his wine are sucking his life, his creativity, out of him. Thus these common people actually become oppressors. And of course, as in previous lyrics, none of them know the real value of any of his work. At the end of the first verse Dylan’s whole situation, running through all his rock lyrics, has been defined. He has been pushed around, drained, and wasted, turned into some kind of freak in his own freak show, and no one realizes what has been happening.

The thief replies to the joker. He understands the joker’s position, and also sees life as a cruel joke (reminiscent of verse four of “Visions of Johanna”). But as he points out, the two of them are through all that confusion now, and there is another destiny awaiting them. Perhaps this is the thief that hung beside Christ, as some like to speculate. The joker then becomes a version of the hanged god (as in verse one of “Desolation Row”) who brings fertility to the land through his death, and salvation to those who drink his blood. The late hour would be the hour of their death. Thus a hint of possible redemption enters the poem.

The last verse sets the scene on the watchtower of the castle. The atmosphere and tone of the verse imply some sort of imminent apocalypse. Princes are on watch. Inhabitants of the castle scurry in and out. It’s almost as if the place is preparing for a final assault from the barbarians. A “wild cat” growls, two strange and mysterious figures approach, and a loud wind begins to blow. The stage is set for some sort of symbolic or mythic confrontation. And that’s the end. It’s over. An aura of expectancy, suspense, mystery has been created, a stage has been set, and then the curtain dropped. All of the questions are left unanswered. What would have been a major breakthrough in Dylan’s poetry, a symbolic confrontation with and resolution of the central conflicts in his career, falters and fails in a breeze.

Dylan finally seems to return to his beginnings as a musician, to one of the first songs he recorded, that concluded: “The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind, the answer is blowing in the wind.” The answer in “Blowing in the Wind” was ambiguous. So is the one in “All Along the Watchtower,” but the image is the same: a wind is rising.

What did it all mean? Dylan seems to have overthrown the question, and in the bedlam escaped the trials of it all with his drifter and headed for the tall timber (“The Drifter’s Escape”). In John Wesley Harding, the rock medium was highly modified for the same reason the rock lyrics were modified—he found the less structured nature of his idiom insupportable just as he found the “real” world grotesque and unacceptable. The results of this clash in both music and lyrics was a return to a simpler, clearer, “cleaner” world, a return to a “primitivist” idiom, accompanied by a self-imposed exile. Dylan seems to have come to the conclusion that the ultimate truths were to be found in those things that “whisper a few simple things eternally.” “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight,” last song on the John Wesley Harding album, and pure Hank Williams, is a song about simple companionship that is also reminiscent of the last stanza of “Dover Beach” or of Camus in The Rebel where he says that those who have found no comfort in the concept of God or in history can find refuge only in concern and compassion for those who, like themselves, are lost in an absurd world. Dylan’s songs at this point seem to imply that the ultimate way a man should be is to have a simple humane concern for his fellow men, and that such basic human emotions are the sources of peace and order. ![]()

“Desolation Row Revisited: Bob Dylan’s Rock Poetry,” by Thomas S. Johnson, Vol. 62, No. 2, Spring 1977.

More From the Archives