Fuckups Are My People: An Interview with Kimberly King Parsons

Interviews

By Robert Rea

There are traditional writers, MOR writers, experimental writers, and then some who are just plain ballsy. Kimberly King Parsons falls in the latter camp, and she does so with style to burn.

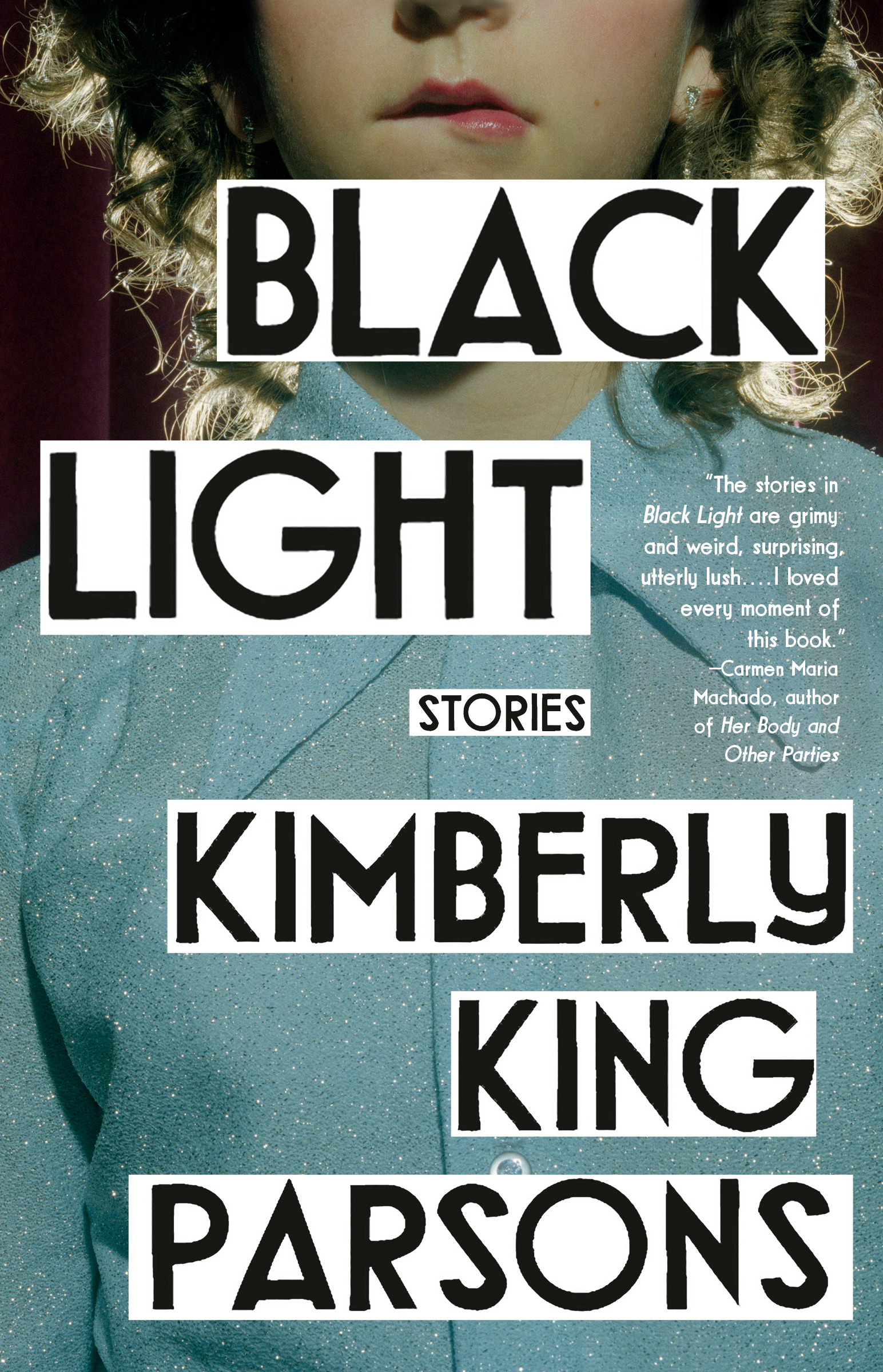

In her debut collection, Black Light, Parsons stays true to her roots, and as an ear-to-the-ground native of West Texas, she has a feel for the rhythms of life in flyover country. If you read that last sentence and thought, Well, that sounds quaint, trust me, it’s anything but. Brash, unfiltered speech and plenty of bad behavior mingle in these stories of last-ditch hopes and small-time failures. Some are about the promise of starting over (“Foxes,” “Black Light,” “Starlite”). Others are about the lure of the open road (“Glow Hunter,” “The Light Will Pour In”). Which is to say they’re about that quintessential American fantasy of escape and reinvention.

Fans of Mary Robison and Barry Hannah—especially the beautifully flawed narrators of Why Did I Ever and Ray—will recognize this strain of voice-driven storytelling. The characters in Black Light are a mixed bag of misfits and malcontents, none of whom have (or want) “a life of wholesome pew PDA with the hubby, clapping on the downbeat, hating the sin, not the sinner. Hair spray, potlucks, half a dozen kids. A big, fat scrapbooking habit.” Most simply want to feel the glow that comes with being alive. But for these folk, small-town life is oppressive, so they get their kicks how and where they can—drinking, drugs, hooking up, more drugs, and the occasional weekender in Dallas to break the monotony. One character sums it up thus: “This place was rock bottom for anybody, a good spot for bad decisions.”

Parsons has already grabbed the attention of NPR and The LA Times, and with a novel slated for next year, she’s a writer to watch. We caught up with her as she embarked on her book tour, and she graciously shared her thoughts on growing up in Lubbock, workshops with Gordon Lish, and, of course, Black Light, which is out now from Vintage.

Robert Rea: What made you decide to be a writer?

Kimberly King Parsons: I grew up as an only child and was kind of spacey and in my head a lot. I was always a reader, but in elementary school I became the designated scary storyteller at slumber parties. I loved that role so much—the captive audience, being around all those other girls in the dark, terrifying them. As soon as I was old enough to realize being a writer was an option, I knew that’s what I wanted to be. I used to want to write whatever I happened to be reading—for a long time I thought I’d end up doing children’s books, later it was YA adventure stories, then horror, but as I grew and changed, my tastes did too, and I landed on literary fiction.

RR: What books changed you as a young reader?

KKP: My parents aren’t readers at all, but they always let me read anything I wanted, even things that weren’t necessarily age appropriate. I used to buy romance novels from this used bookstore near my house when I was probably in fifth or sixth grade. They were five for a dollar, and I would buy the ones with the nastiest names or the most graphic covers I could find. Those books have a pretty rigid formula, so you know the sex will be every thirty pages or whatever. Obviously, I’d skip straight to those spots and dogear those pages. I was reading that stuff because I was curious, of course, but there was something else going on too. The feeling those books gave me—it was arousal, but not exactly sexual. It was the same feeling I felt reading horror, which I was also reading a ton of at that time. There was some fear and some confusion. Some anxiety. Total immersion. It was so crazy to me that words on a page could make me have such a visceral response. I found that wildly appealing.

RR: Tell us about the origins of Black Light. How did you start writing it?

KKP: I started the earliest stories in 2005 when I was in the MFA program at Columbia. I didn’t know I was writing this particular collection back then, but I’ve always adored story collections. The books I found the most moving as a young writer were stylish, voice-driven story collections: Amy Hempel, Lorrie Moore, Joy Williams, Barry Hannah. But back in those days I was under the mistaken, kind of ridiculous impression that I should be writing a novel, that the short stories were in preparation for that. It took me a while to realize I needed to write the thing that got me off instead of the thing that I felt like I was supposed to be writing.

RR: Several stories—I’m thinking of “Guts,” “Glow Hunter,” “Black Light”—are about being young and rebellious. What is it about this theme that appeals to you as a writer?

KKP: There’s something so tender and stupid about being a teenager—everything is dramatic and earnest, or else so shot through with coded sarcasm and odd slang, it’s impossible for anyone on the outside to understand. No well-meaning teacher or parent or shrink can really get through to teens. There’s a line in a Neutral Milk Hotel song that goes, “Out in the dark, the world is still rolling / Kids in their cars, cigarette smoking / And all that they are just reeks with the sweetest belief.” I love that reek—looking into those dark cars and seeing kids in that short, exquisitely painful phase of becoming. Teenagers are also wading through a time of intense experimentation, introspection, and low impulse control, and I’m compelled by all of those things. I like that you include “Guts” in there. Sheila and Tim are young adults with real responsibilities—he’s about to be a doctor!—and yet they are both so childish in many ways.

RR: So many of the characters in Black Light are weirdos, fuck-ups, outcasts—people on the fringes. Was this a deliberate choice?

KKP: I didn’t plan it that way, but fuckups are my people. I can’t imagine trying to construct a story around a secure, confident character making all the right decisions—I actually don’t believe people like that really exist? I think healthy people are an urban legend. I’m always trying to find the flaws, but never to take somebody down—I’m looking for opportunities to be radically empathetic. Fringe characters, misfits, and outcasts get you to that place a little faster, but I think even the most well put together among us are always on the cusp of losing their shit—some people are just better at hiding it.

RR: Recreational drug use seems to be one way for the characters to deal with the fact that they’re outsiders. Or does taking drugs make them outsiders?

KKP: So, weed is legal where I live, and I already knew this just from being a person in the world, but I actually find recreational drug use to be pretty damn unifying. It seems to me that it’s not only outsiders dipping into those substances, but people very much on the inside participating as well. Go into any weed shop and you see frat guys and transients and soccer moms and professionals in suits all throwing their money at it. I think we can extrapolate that to other recreational drugs as well.

I don’t buy into the idea that people use drugs purely to escape—I mean, that can be a bonus, if escape is what you’re looking for, but I think just as many people use drugs to pin them to the present moment, to enhance, or to prolong. Or because drugs can be fun. Fun is an often minimized part of the drug narrative, which seems nuts to me because I think most people initially approach being altered from a curious, inquisitive, childlike place. What’s this gonna feel like? Plenty of people experiment and walk away better for it. Obviously, drugs wreck lives too, and that’s the narrative we’re familiar with—the idea that drugs will turn you into a loser or an outcast or an addict. Some of the characters in Black Light might be edging towards that a bit, but some certainly aren’t. I don’t have a problem putting those two competing views in the same book. The way I see it, these are fringe characters and some of them happen to do drugs. But some of them have brown hair or glasses or bad teeth. Drug use is a trait but not necessarily a defining one.

RR: Most of the collection is set in Texas. How does that shape your fiction?

Texas is where I grew up and formed my core personality. I left fifteen years ago, but it’s such a huge part of who I am. When I lived there, I was too close to see the strange, beautiful details, but once I moved to New York, I could look back and see it in all its weird glory. From a very young age, I had a feeling like I was missing out on something, like I was on the outside of things—maybe it was coming from books I read or movies I watched. Even as a little kid, I felt sort of socially and politically stifled—living in Lubbock and spending a lot of time out at my grandma’s house in the panhandle just gave me this feeling like Isn’t there something more? But then of course I ran away to New York and immediately started pining for home. I started recalling the voices that shaped me and the places I spent so much time when I was little, just doing nothing, wandering around, killing time. All of that started showing up in my stories, and it felt both familiar and magical.

RR: One of my favorite stories is “Glow Hunter.” It tells the story of two road-tripping girlfriends, with shades of Thelma and Louise. If the story were optioned for film, which actors would you cast in the leading roles? Also, which songs would you pick for the soundtrack?

KKP: I wish I was familiar with more young actors! Do we think Saoirse Ronan could play a teen and swing a Texas accent? Alia Shawkat would be a terrific Sara too. I don’t care that she’s thirty—I just want to watch her face for my whole damn life. For Bo we might have to time-travel: Gummo-era Chloë Sevigny or Natural Born Killers–era Juliette Lewis? I’ve had my head down raising kids and writing books for the last decade—I’m probably missing tons of amazing possibilities.

As for the soundtrack, I made myself stop at fourteen songs for no real reason because making playlists is my very favorite thing. These make me think about highways.

Smog—“Hit the Ground Running”

Perfect start to a road trip.

Yo La Tengo—“Stockholm Syndrome”

“I know it’s wrong, but I swear it won’t take long.” And the claves always kill me.

Of Montreal—“The Past Is a Grotesque Animal”

Plug into the whirring imagination and bizarre, celestial beauty of Kevin Barnes—perfect start to another kind of trip.

Dirty Beaches—“True Blue”

The first time Alex Zhang Hungtai hits that high note is just. Yeah.

TV on the Radio—“Dreams”

“Bartering bellowing/Barracking blundering/Pillaging plundering/Living and lavishing”

Modern Lovers—“Astral Plane”

Where you go when the one you want doesn’t want you. Also, such a good road beat.

Cat Power—“(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”

Sometimes there’s no greater satisfaction than not getting what you want—in this case the chorus.

Silver Jews—“Random Rules”

“I was hospitalized for approaching perfection.” Jesus, I’m so sad Berman is gone.

Pavement—“Transport Is Arranged”

“I could trickle, I could flood.”

The Fall—“Midnight in Aspen”

“He aims the highest bestest powered rifle at the stars.”

Lower Dens—“Truss Me”

Jana Hunter’s voice is dusty highway heat.

Songs: Ohia—“Coxcomb Red”

“I wanted in your storm so bad I could taste the lightning on your breath.” I mean.

Virgil Shaw—“Sing Me Back Home”

Virgil has the voice of a goddamn angel, and I love anybody able to do Merle justice.

Parquet Courts—“Uncast Shadow of a Southern Myth”

The screamy part at the end gives in to the bottled rage that’s been there all along.

RR: You thank Gordon Lish in the acknowledgments for Black Light. How instrumental was he in your development as a writer?

KKP: He was critical. He’s been influencing me since I was a teenager, through the writers he has edited or published—Hempel, Carver, Raffel, Schutt—though I didn’t know him as a teacher until 2009. It was an epiphany to trace all my favorite voices back to him, and it blew my mind being in his workshops over several summers. He’s a polarizing person in the literary community (and I completely understand why), but my taste is almost always in line with his. He’s also hilarious and fun to be around—I think people talk about him like he’s this harsh, terrifying presence, and he certainly can be, but he’s also so damn funny. The biggest takeaway I got from Gordon is recursion: every sentence has to speak to the sentence that came prior. It sounds so simple, and yet it’s astonishing advice. It’s also very comforting to know that all of the answers are already on the page.

RR: You have a novel coming out next year. What can you tell us about it?

KKP: It’s not such a dramatic departure subject-wise from the stories in Black Light: a new mother living in New York City has to return to her small Texas hometown to deal with her hoarder mother. It’s also about disordered thinking and songwriting and LSD and grief and sibling relationships. I’ve been working on it for what feels like forever, but I can finally see the whole shape. It keeps getting weirder and weirder, which I’m definitely okay with, and now it’s gotten to the point where it’s always buzzing in my back brain, though my feelings about it are constantly changing. Yesterday it was a huge pain in my ass—today I kind of like it.

Robert Rea is SwR’s deputy editor and web editor.

More Interviews