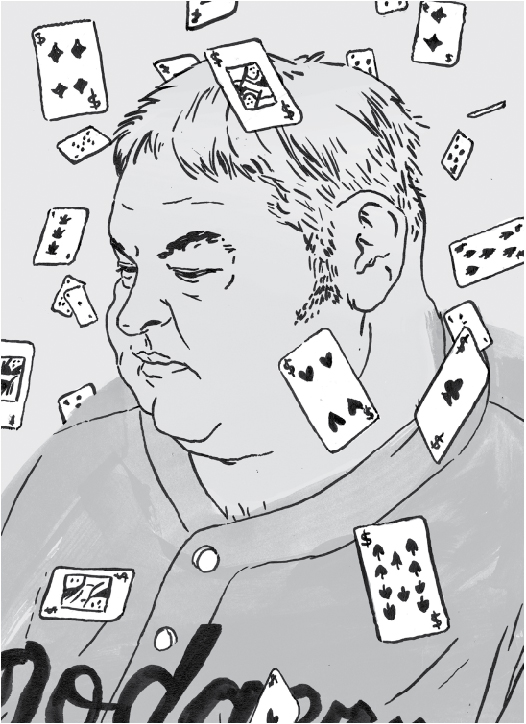

illustration by CALUM HEATH

I

f Uncle Ray walked up on two rats screwing in an alleyway, he’d want odds on which one was going to come first. He’s an unrepentant gambler, or as my dad calls him, “a degenerate piece of shit.” I first heard Dad say that when I was fifteen, on the Saturday when Ray was picked up at our house for owing child support. “The bitch must’ve tipped them off,” Dad said, talking about Ray’s ex, Sheila. “The bitch.” That’s what Dad always called her, and he called their kids “bastards,” as in, “Those poor bastards don’t stand a chance under the sun.”

I guess he was sort of right: R. J.—Raymond Jr.—lives with his mom. He sleeps all day and plays video games all night. His sister, Jessica, is a receptionist in the city. They’re not dictionary definitions of failures, but they’re close enough. I’m not saying that I’m doing much better. I’m between gigs at the moment. Dad wanted me to go to work with him stringing wire and then take the exam to get my contractor’s license. It didn’t sound all that interesting to me, and besides, he hates his job. So I worked at the tire shop until I figured out what I wanted to do with my life. Now I have, and my path seems pretty clear: I’m going to work with Ray.

I know Dad’s probably right about Uncle Ray. He was definitely a bad husband and a bad father. He always talks about how much he misses his kids, but he never does anything about it. But that’s not my problem, so I like Ray just fine. He’s a big, fat, funny fucker. He lives in a basement apartment on the South Side of Chicago in Beverly. I go over there a lot, mostly to watch movies with him. It’s a good place for movie watching because there aren’t really any windows at Ray’s place, just little slits up near the ceiling that look out onto the sidewalk. The darkness makes it feel like a theater. It even has a sticky floor. And Ray loves movies. He has a big stack of DVDs, and he always has one playing whenever he’s at home. He once told me that he even sleeps with the TV on just for the noise.

A couple of weeks ago, we ordered pizzas and had a double feature—Godfather and Godfather Part II—and we got to talking about a dream Ray had. He kept calling it a “premonition.” He said the last time he had one of those, he sold a bunch of his stuff, went to Vegas, and came back ten grand richer. He said he lived like a king for about three months after that. Ray tells people that we’re a quarter Indian, and that the spirit world speaks to him through his dreams. Our last name is Mullen, and most of us have red hair, so I doubt it. But you can’t argue with results—if it worked once, then who’s to say it won’t work again?

Anyway, during the scene in Part II when it’s the old days and Vito Corleone kills the guy in the white hat, Uncle Ray told me about his dream. “Listen to me, Bobby,” he said. “This is what I saw: I was raking armfuls of chips, and you were there next to me. I saw it as clearly as I see you right now. The two of us were at the table, we flipped the cards, and that was it,” and Ray pounded his fist into his hand.

But he didn’t just have a dream—he had a plan. We would go down to the casino in Joliet, where nobody knew Ray. He can’t gamble in Rosemont or at the ones over the border in Indiana anymore because he said they noticed him working his system. But he told me not to worry. “Hell, Bobby, it took ’em weeks to figure out what I was doing before they gave me the boot. We’re talking about one night. They deserve to take a loss every once in a while, right? Everybody else does.” That made me feel better. And he’s right—the casinos are greedy bastards. Half the shit that Ray’s lost in his life, he lost to them. They only showed him the door when he started winning.

Ray said we were going to find the table from his dream, sit down, and wait for our fortune to arrive. We had to get there late at night—three, four in the morning—because that’s when they deal cards from a single deck at the blackjack tables. According to him, it’s easier to keep count with a single deck. He kept harping on the fact that we needed to keep our eyes open for a “guide.” There had always been a guide to accompany his visions in the past, someone who pointed him in the direction of the riches. “When they show up, I’ll know it,” he promised.

After the Godfather night, Ray started teaching me his card-playing method. I was never good at math, so it took some time, but I think I more or less understand. I quit my job at the shop so we could have more time to practice. Night after night, Ray and I would sit at a little folding table in his living room with a deck of cards and a movie on in the background. Sometimes we went to the twenty-four-hour pancake house a few blocks away and sat in a booth against the back wall where no one would bother us.

Two days ago he told me that I was as good as I’ll ever be. He told me to take out whatever money I had and be ready to go, which is what I did yesterday morning at nine when the bank opened. Then I went back home to get some sleep. When I opened our front door, I walked right into Dad.

“Why are you still here?” I asked him, surprised to see him home so late in the morning. Apparently it had gotten so cold the night before that the battery in his work truck had died. I was sort of sorry that I hadn’t been there to help him, especially when I saw him shivering while trying to zip up his coat.

“Where you been?” he asked on his way out.

I held my breath. “At Ray’s,” I said, trying to get past him and up to my room as quick as I could. For some reason he didn’t blow up like he normally did when I told him I’d been with Ray; he just sat his coffee cup down, pulled on his gloves, and kept going like he hadn’t heard me. I was still staring at him when the door slammed shut, leaving me alone in the dark entry hall.

I slept off and on throughout the rest of that day. Every time I’d wake up, even for a second, I’d instantly start thinking about cards. Diamonds, hearts, spades, and clubs. Red and black, face cards and numbered cards. I tried to chisel everything that Ray had taught me into my memory.

Finally, around ten that night, I got up and started getting ready to go. Ray said he’d pick me up out in front of our house at midnight. I walked downstairs to watch TV in the living room while I waited, but Dad was there sleeping in his recliner. The Blackhawks game was on with the sound turned down low. I walked over and stood next to his chair to see if he would wake up, but he looked beat to hell, still wearing his work clothes with his head hanging to one side and his mouth wide open. All I could think of was the mantra that Ray always repeated. “Easy money spends just as well as hard-earned money does.” I grabbed a blanket off the back of the couch and threw it over Dad; then I turned off the TV and the lights and waited by myself in the kitchen for Ray to show up.

He and I hit the road for Joliet just as the snow was starting to come down hard. The big flakes looked like they were being fired out of a shotgun in front of us. They swirled around the windshield, thousands and thousands of them, until they closed in on us like a tunnel. It made me dizzy and a little nauseous, so I rode most of the way with my eyes closed. The heater in Ray’s little Toyota pickup truck would shut off every time we hit a pothole, and the windows kept fogging up, but I didn’t complain.

He pulled off the interstate in La Grange and stopped to fill up the tank. Ray asked me to pay while he took a piss. Inside, I grabbed a Dr Pepper from the cold case and bought fifteen dollars in gas. Thank goodness Ray’s truck doesn’t drink much, because I didn’t have any more to spare. I had pitched the rest of my funds into the “card game kitty,” as Uncle Ray called it. He had that stowed away in the truck’s console, and we agreed to not touch it until we got to the table.

Outside the station, I stuck the pump in the tank and waited in the passenger seat to keep warm. Even with the fur collar pulled up around my cheeks, my denim jacket wasn’t much against the wind on a night like that. A new coat was the first thing I was planning to buy with my share of what we took home from the casino.

Ray was taking a long time, but finally I saw him through the storefront window as he came out of the bathroom and walked to the counter, where he said something to the cashier. Then he came outside and got in the truck, still smiling from whatever the guy inside had said back to him.

“What was that all about?” I asked. Then I widened my eyes. “Was that him? Our guide?”

“No, no,” he said, chuckling to himself. “I told him he had a nice store; then I told him to take a good look because he just might be looking at his future boss. That’s how you get ahead, Bobby. You make some money; then you invest it and let your money work for you. That way even when you’re sleeping or sitting on a beach somewhere, your money’s still making money. A little store like this in a town like this? That’s a license to print money. I’m looking to buy something like that with our winnings. Get a house somewhere big enough for the kids and me, maybe their mom, too. You never know.” Then he stopped smiling and gave me a dead-serious look. “How much change did you get back after buying the gas?”

“I don’t know, a couple of bucks and some coins.”

“Can I see those dollars?” he asked. It seemed funny, but I dug the bills out of my wallet and handed them to him.

Ray looked up toward the sky and smiled. “I knew it,” he whispered to no one. “I knew it.” He was grinning so wide that his fat cheeks swallowed his eyes.

“You knew what?” I asked.

“See the year on these dollar bills? Nineteen seventy-one—both of them. That’s the year I was born. I swear, I saw all of this in my dream. Everything, even down to the amount of change you were going to get back. The way the lights are reflecting off that puddle over there—all of it. It’s all familiar. I’ve been here before.”

Ray handed them back to me, and sure enough, they were both dated 1971. He was shaking, and his voice rose a couple of octaves when he spoke. Up to that point I hadn’t really believed what Ray said about his dream. I mean, I believed that his blackjack system worked, and I was convinced that he was due for a lucky streak. The dream stuff just seemed like nonsense. But something about his expression at that moment converted me. Even the best liars don’t have that kind of conviction. Ray had the look of a man who knew how his story would end. I folded the bills and put them back in my wallet, more determined than ever to make that money work for me.

We crossed the river into Joliet just after one in the morning and walked into the casino shortly after that. It was my first time inside one. It surprised me how nice the place was, with the thick, dark-red carpet and gold trim. The air was warm and clean, with a hint of cigarette smoke. I wanted to stop and put some money into one of the ringing slot machines, but Ray pulled me away. “Come on, those things are bullshit,” he said, grabbing my arm. “Go stick your quarter in the soda machine out front; at least you’ll get something back.”

He led the way through the slots, past the roulette tables, craps tables, and something called pai gow until we reached a row of blackjack tables. Every stool was occupied, so Ray hung back and watched the action. “It’s too early,” he said, watching the dealer slap cards down on the green felt. “They’re still using three decks. We’ll come back.” He turned in a circle and craned his neck to scan the edges of the big room until something caught his eye. “Over there,” he pointed. “Let’s get something to eat.”

There were only about ten people seated at the tables inside the Billion Dollar Buffet, mostly gray heads, with one table of young guys who looked like they were in the middle of a long night. Ray grumbled about the amount of noise they were making, but he quickly let it go and turned his attention to more important matters. He fumbled in his jeans pocket and pulled out a deck of cards. “All right, Bobby, let’s go over it one more time.” He stopped talking and covered the cards with his hands when the waitress came around to take our drink orders and again when she dropped off our plates. We paused the game long enough to load up on omelets and bacon from the breakfast section of the buffet.

When we got back to the table, Ray took out the cards again. “Okay, where were we?” he asked.

“Show me again how I’m supposed to signal you if we aren’t sitting next to each other.”

“That’s a great question. If we end up seated a couple of chairs down from one another—and hell, even if we do happen to sit together—and you realize that you’re on the count, I want you to tap the cards with two fingers, like this,” he said, extending the middle and pointer fingers on his right hand, pressing them together, and touching them to the table. “Do it nonchalant-like, so that no one notices. Act like it’s a nervous tick or something.”

Our waitress came back by and placed two cups of coffee down in front of us. I would have preferred a cocktail, but Ray made a rule that said we couldn’t have alcohol. At least not until we were celebrating. I watched him turn up the little silver pitcher of half-and-half over his cup and dump nearly all of it into his coffee, stirring it with a spoon in his other hand until it overflowed into a puddle on the table. He stopped and stared into the spinning, cream-colored concoction; then he closed his eyes, like he was praying, and sat silently.

“What is it?” I whispered.

“I’m just checking in, making sure that this all matches up with my dream. We can’t have anything out of place.”

“Was there coffee in your dream?” I asked. My chest felt like it was going to explode.

Ray nodded and smiled before closing his eyes again. “What color hair did that waitress have? I wasn’t paying attention.”

“Blonde, I think. With some gray in it.”

“Good,” he answered. “That’s what I thought. We’re on the right track. I’m still looking for the guide, though; that’s the only thing that’s missing. It could be the dealer, or it could be this waitress. I’m always surprised by the person. Now, what do you do if you draw a twelve, I’m showing ten, and the dealer is showing a three or above?”

Before I could say anything, out of nowhere, a sugar packet hit Ray’s shoulder and fell to the floor. There wasn’t any doubt about where it had come from. He and I both turned and looked at the table of young guys, the loud ones. They had their heads down, shaking with laughter but trying to hold it in so that we wouldn’t notice. Ray growled under his breath.

“Like I was saying, what do you do in that scenario?” He laid the cards out on the table to illustrate what he was talking about, and I thought through what he had taught me. Just then another sugar packet landed in his cup, spilling coffee all over the jack of diamonds that was lying on the table. “Sorry,” came a slurred apology from behind us. One of the guys, a tall, lanky one wearing a Bears jacket, came over to us.

“Hey man, I’m sorry about that. My friends are acting up,” he said. I could smell his beer breath from five feet away. “Let me get that for you.” He reached into Ray’s coffee with two fingers, pulled out the sugar packet, and closed his fist around it. “They can’t handle their liquor. I’ll try my best to keep them straight.” He said that last part loud enough for his friends to hear, to which they answered back at him with a barrage of fuck yous.

“From what I can tell, none of you can handle your liquor,” Ray said, staring him down.

“Hey, I came over to apologize. I didn’t even throw the damn thing—it was one of them,” the guy answered, shifting his glance from Ray to me, then back to Ray. “Just chill the fuck out. I said I was sorry.”

I could feel Ray’s foot bouncing on the table leg. He was going at it so hard that he shook the puddle of spilled coffee right off the table top and onto my lap. But he didn’t say a word; he just stared at the younger man. All of a sudden, without warning, Ray pushed his chair back from the table. The loud screech that it made when the legs scraped across the tile floor jolted me up and out of my chair too.

It would be hard to say that Ray looked scary, with his big gut hanging out from under his T-shirt and his belly button showing for all the world to see, but he had a look on his face that froze me where I was. I didn’t know what to do when he took the first swing. He smacked the kid right on the side of the neck, just below his chin. As soon as they heard the crack of contact, his friends were up from their table and right on top of us. Two of them grabbed me so I couldn’t help, but I doubt that I would have tried to anyway. The one that Ray had hit bent down on one knee while the other two started throwing punches at Ray.

It was my first time to see a fight between grownups. Ray covered his face with his arms while they took big, wide swings at him. Then I felt a hand jerk me from behind. In the melee, three security guards had surrounded us. One of them put the bigger of the two guys who were beating on Ray into a headlock and dragged him down to the floor. When his friend saw that, he stopped swinging at Ray too. One of the guards had a hand on each of the guys who’d held me, and the third one warned me not to move. The guy who Ray hit, the one that had started it all, was still kneeling on the ground trying to catch his breath.

I started to move toward Ray to help him stand up, but the third guard clamped a big hand down on my shoulder and pushed me toward the door and out into the casino. Some of the other diners had stopped to watch us, and I felt embarrassed at the scene we’d caused, especially since I hadn’t been drinking.

“If you keep fighting me, you’re going to get hurt,” the guard said, grunting against my weight. I hadn’t realized that I had been leaning back on him, trying to keep him from leading me away from Ray. He twisted my right arm behind my back and kept hold of my left one as he drove me through the crowd on the casino floor. I tried to look back and see if Ray was behind us, but the guard stopped me every time I went to turn. “Keep walking,” he ordered.

“Where are we going?” I asked as we approached a door next to the cashier’s cage.

“To the place where we keep fight-starting assholes until the cops can get here.”

“Am I going to jail?”

“That’s between you and the cops, but I’d say probably so.”

When he said that, I felt a burning in my throat, and my eyes began to sting a little. Shit, I didn’t want to cry, especially with people watching, but I was afraid I wasn’t going to be able to help it. More than anything, I wanted to see Ray. He could fix whatever jam we were in. The guard stuck a key card against a square reader next to the door, opened it, and shoved me inside. To my left I could see two old women making change at the cashier’s counter. They didn’t even look up when we walked past. As the door was closing, I heard something that made me forget all about crying.

“When I call my lawyer, you’re fucked. Your rent-a-cop buddies too.” It was Ray.

“You’re about to talk yourself into more trouble than you bargained for,” one of the guards shot back.

I felt my guard’s grip loosen just enough that I could look over my shoulder. There was Ray, blood running down his face from a gash over his eye, both hands behind his back, thrashing from side to side like a wild bronco. It took both of the other two security guards to keep him in line. Following along, with their heads down, were the five boys from the café. It was funny to me that the guards didn’t have to drag them like they did Ray and me. I felt tough.

“The more you resist, the worse this is gonna get for you,” one of the guards told Ray, but he didn’t seem to hear or care.

“Fuck you” is all that he said.

We came to the end of a long hallway. The guy escorting me told me to stand still while he pushed the down button on a beat-up–looking elevator. I felt Ray and the others close behind me while we were waiting. Ray was breathing heavily, but he had stopped talking. When the doors slid open, I was pushed inside the metal box and told to face the corner. One of the guards instructed Ray to do the same in the opposite corner, and the others packed in behind us. I caught a glimpse of Ray through the side of my eye. He looked sad, like all of the anger and bravado had left his body and he was just an empty shell.

I tried to get his attention, but he didn’t seem to notice me. His hands were stuck together behind his back with zip ties. Bastards, I thought. Why’d they have to do that to him? Then I heard the elevator bell go ding, and the doors opened.

“All right, everybody out,” said one of the guards. Another one led Ray and me to an office while the others went the opposite way. He flung the door to the office open, turned on the lights, and pointed at two chairs across from a bare desk. I went in first and took the chair closest to the wall, and Ray sat down next to me. The security guard closed the door and left us there alone.

“You okay?” Ray whispered, arching his back to get comfortable with his hands behind him. “These things are cutting into my wrists like hell.”

“I’m all right. Those guys grabbed me, but they didn’t really hit me. Sorry that I wasn’t more help.”

Ray shook his head. “Not your fault. Five on two. I should have known better. At least I got one good shot in—did you see the one I hit first? Shit, I thought he was gonna suffocate. Even the biggest dude will go down if you clock him in the throat like that.”

“That was a good shot,” I said, feeling ashamed of myself for not taking a swing at one of them myself. “What do you think will happen?”

Ray scrunched his face and looked at the ceiling. “Probably nothing. The cops will come, they’ll talk to all of us. Those guys’ll say we started the whole thing, we’ll tell them the opposite happened, and that will be it.”

That made me feel better, but I noticed that Ray’s face had dropped again. He looked worse than he had in the elevator.

“What’s wrong?” I asked quietly.

Ray stopped fidgeting and let his arms and shoulders rest against his wide, round back. He shut his eyes, and a tear actually came out. Then another and another, running down his face in little shiny lines.

“This was it, Bobby—the first sure thing that’s come my way in a long, long time. And I fucked it up. All I had to do was sit there and keep my mouth shut and keep my hands to myself. If I had, we’d be upstairs right now making money hand over fist.” On that last word, his voice cracked. “This temper. It gets me every time.”

I was glad they hadn’t cuffed me, and I reached over and put my arm around Ray. His big shoulders bounced with his sobs. It felt strange to touch him, but I didn’t know what else to do.

“We’ll have another chance,” I said, trying to make him feel better. “Maybe not here, at this casino, but somewhere else. There are casinos all over the place. Hell, I’d even go all the way up to Detroit if you wanted to.”

Ray snorted, then he looked at me and grinned. “No, this was the time. I know you don’t believe in my premonition. If I were you, I wouldn’t believe in it either. But it’s a fact, just like us sitting here is a fact. Just like it’s a fact that there won’t be another time. It had to be tonight—that’s what the dream told me. The time and place were very specific. We took a left turn when we were supposed to take a right. I’m mostly sorry that I cost you, Bobby. You don’t have any idea of what you could have done with that kind of money. I know you’re not a working man like your dad. You’re more like me. I don’t trust hard workers. Why are they working so much? They’re running from something—they’ve bought into that old Protestant work ethic idea, where if you keep busy you won’t sin. From what kind of sick, twisted urges must a working man be running? But you and me, we aren’t sinners, and a haul like tonight could have kept both of us afloat for a long time.” Then his head dropped to his chest again.

“Don’t beat yourself up,” I said. “I did believe—I do believe, I mean—in what you said about your dream. And that dream meant that someone or something out there in the universe thought that you were worthy enough to be rich. Nothing’s changed; they’ll give you another shot, I’m sure of that.”

Before Ray could respond, the door opened, and a gray-haired, balding man walked in wearing a black suit and tie with a mustard-colored shirt. I remember thinking it was the ugliest combination of colors that I had ever seen. He sat down at the desk in front of us, unclipped the radio from his belt, and sat it on top of a metal file cabinet.

“Found yourselves in a little mischief tonight, I hear,” he said matter-of-factly. His head was cocked back, and he looked down at Ray and me over the top of a pair of reading glasses perched on the end of his nose. “The guys in the other room over there said you started it—is that right? Care to tell me why?”

“We didn’t sta- …,” I began to say, but Ray interrupted.

“That’s their story. What did you think they were going to say—that it was all their fault? You don’t have a damn thing on any of us. Why don’t you just cut us all loose so we can be on our way?”

Mustard shirt smiled. “You sound like a man who’s been here before.” He took a long, deep breath and looked at us over the rim of his glasses. He and Ray stared at each other for what felt like an eternity—at least a full minute—without saying a word. Ray had been breathing heavily since we sat down in the office, but I felt his big frame relax next to me in the midst of the silence. His inhales and exhales slowed, and I stopped hearing the wheeze through his nostrils. “Why don’t you tell me your name,” Mustard ordered.

“Ray,” he answered softly. That old defiant tone was gone.

“Why did you do it, Ray?” Mustard asked, his eyes softening. He took off his glasses so that he looked less like a man who wanted to toss our asses in jail and more like a disappointed father.

Ray sighed and shuffled his feet underneath him. “You know how it goes. Those young ones needed to learn a lesson. I figured that responsibility fell on me.”

Mustard shook his head. “You don’t want that kind of responsibility. I have it, and it’s not something I enjoy. You think I like being the heavy? Coming down here to discipline a bunch of grown men? This isn’t fun for anyone, especially me.” His radio crackled from on top of the file cabinet, and out came a barrage of muffled, broken sentences. Mustard reached behind him without looking and turned it off. “You’re what, forty years old? Probably have some kids. And this young man,” he said, pointing at me, “looks like he admires you like some kind of superhero, and you’re getting into a fight in the middle of a buffet. Hell, Ray, this is a family kind of place, not a Wild West saloon. It’s a shame, but frontier justice died a long time ago.”

I looked over at Ray and tried to gauge what he was thinking. I honestly couldn’t tell if we were in trouble anymore or not. Mustard had leaned back in his chair and seemed to be thinking about what he wanted to do with us when there was a knock on the door that made me jump. Mustard stood up from his desk, clipped the radio back on his belt, and smoothed his tie against his stomach before buttoning his suit coat. Then he did something that I couldn’t believe—he walked around and stood behind Ray’s chair, pulled a knife from his pocket, and cut the zip ties off his wrists before looking at me.

“No handcuffs?”

“No, sir,” I answered.

He gave me half a grin and nodded in approval. “Good man,” he said. He folded the knife and pulled a black leather wallet from his coat pocket, out of which he took two crisp one-dollar bills. “Here,” he said, holding them in front of Ray. “Go upstairs and get some coffee before you hit the road. It’s late, and I don’t want you dozing off and ending up in a ditch. I can’t have that on my conscience.” Ray never looked up, so I reached over and took the bills and put them in the side pocket of my jacket. With that, Mustard opened the door and left us alone again.

I got up first and helped Ray to his feet. He stood and rubbed his fingers over the red lines on his wrists. I held the door open for him, and we walked out into the hallway. But I couldn’t remember from which way we had come. After two wrong turns down two long, quiet hallways, we found the elevator and headed back upstairs.

When the elevator doors opened on the main floor, I was still thinking about Mustard, amazed that we had gotten off that easy. I pushed opened the heavy steel door next to the cashier’s cage that led back to the casino floor, and we stepped out as free men. The noise from the machines brought me back to my senses. Seeing and hearing it all again for the second time that night, nothing about the casino seemed all that nice anymore. What had been a sweet, smoky aroma when we first arrived now reminded me of how shitty and stale our house smelled when Dad used to smoke a pack of Camels every day. The red carpet that I had thought looked so nice before just looked dull and worn, and the people pumping dollars into the slots looked about the same. It wasn’t the kind of place where a fortune was to be won. I was ready to leave, but the thought of going home and forgetting the whole thing made me sick to my stomach. What was I going to do, go back and go to bed? Get up and go to work the next morning, and the next morning after that, and all the mornings until I was too old to do it anymore, coming home every night so dog-ass tired that I barely had enough energy to eat dinner and watch the Sox game before falling asleep in front of the TV and waking up to do it all over again?

It was nearly four in the morning by the time we walked out of the casino, but the parking lot was still full. We searched the rows of cars until we found Ray’s truck. He still hadn’t spoken since we left Mustard’s office. The truck doors creaked open, and piles of snow fell from the door panel onto the floorboard as we got inside. I rested my head against the window and could have fallen asleep right then and there. Over in the driver’s seat, Ray looked about as tired as I was.

“You good to drive?” I asked.

He grunted something close enough to a “yes” and started the truck. I hated seeing him like that. We were sitting still while the truck idled and the engine warmed when I remembered the money that Mustard had given us. I leaned forward and pulled out my wallet, took two dollar bills from it, and looked at them in the pale glare from the light post above us.

“Look look look!” I shouted, grabbing Ray by the arm. “Look at the year on these bills that security guy gave us!”

Ray turned to me with a blank look. “What?” he asked, reaching down to the shift knob to put the truck into reverse.

“No, wait—before we go, you have to look at this. The dollars that the security guy gave us for coffee, remember? When we were sitting in his office? Nineteen seventy-one—that’s the year they were made. Just like the others. You said it was one of the signs from your dream, right?”

Ray shifted his eyes toward my hands but remained quiet.

“Really, I mean it. Look for yourself.”

Ray sighed, and I laid the bills in his palm. He stared at them for several moments, then folded them in half and gave them back to me. Then he grabbed the steering wheel with both hands and looked out at the snow-covered lot.

“See? What did I tell you?” I shouted. “Didn’t you wonder why we got off so easy? They had us dead to rights, and they just let us walk out of there. The guy in the suit wasn’t a security guard; he was the guide that you were looking for. That’s why he gave us the money, and that’s why there’s that date on those dollars. Don’t you see? It’s not over. I mean, it’s over tonight, but we’re being told by a power greater than the two of us that we can try again. This is proof that your dream was real.”

Ray tried to stay stone-faced but couldn’t help himself. He squeezed his eyes together, and his mouth broke into a tight little smile.

“I can’t believe it,” he gasped, letting himself begin to laugh just a little. “I just can’t believe it. I keep screwing up, but the chances keep coming.” He let out a long, high-pitched whistle and turned toward me. “Why am I so lucky, Bobby? Can you tell me that? Look at the bright side—we still have our money stash.” He was the old Ray again. “We live to fight another day,” he said, reversing the truck out of the parking space. “Let’s go find someplace to eat and talk about our next move.”

“Let’s do it. That money’s not going to do us any good back in the bank. Let’s put it to work, right? The only way you get ahead is when your money is making money for you.”

“That’s right,” Ray said, smacking me on the knee. “That’s absolutely right. Just follow the signs. They’ve never let me down.”

I took the folded dollars that Ray had handed back to me and put them back in my wallet. The bills from the casino’s security manager were still crumpled in my jacket pocket. I couldn’t tell you in what year they were made. But we lived to fight another day. ![]()

Read Next

Do Your Best