The place is Mildred M. Fox School, in South Paris, Maine. The time is recess. The game is kickball, the center of your recess universe. The basics of kickball:

1. Soccer-sized ball of red rubber. Springy and forgiving to the toes when kicked, sharp and stinging when you catch it.

2. Field and rules just like baseball, except

3. Pitcher rolls the ball on ground. (Amount of bouncing allowed is hotly debated.)

4. Batter is actually a kicker.

Oh. And.

5. All the players are boys.

Mildred M. Fox is a brick square, two stories tall. Behind it there’s a steep drop-off to the Little Androscoggin River, a slope cluttered with saplings, leaves, branches, and trash. The margin of the schoolyard is bounded by a chain-link fence. Anything over the fence and down the riverbank is off-limits. A ball kicked over the fence elsewhere (say, on the side that borders the nursing home) can be, with teacher permission, retrieved. But the slope has been deemed too steep and hazardous.

So, kickball is played out front. Less danger of losing the ball (of which there is always only one). Between the back and the front: a woodchip-covered playground with swings, tires, monkey bars, four-square courts. All of these are for kindergartners and girls. There’s an open rectangle for tag. Tag is co-ed. But only for lame (lame is not the word you would have used then, but you are too embarrassed now to even type the word you would have called them) boys. The front is pavement. It used to be the teachers’ parking lot, but now they park somewhere else. They say they’re going to tear up the pavement and put down grass or woodchips, but they haven’t, and they’ve been talking about it since you were in kindergarten.

It is 1985. It is spring. But it is also Maine, so there are still snowbanks. (You learned to ride without training wheels just last year at this time. It was perfect: whenever you got wobbly, you’d steer for a snowbank and tip over, cold but safe.) Your teacher is Mrs. Burns. You like her. She is tall and wears nylons and drinks from a Styrofoam cup of McDonald’s coffee in the morning. You like her though you hope you won’t end up being like her. You hate nylons, even the thought of them. Once you told Mrs. Burns that she had spinach stuck in her front teeth and she thanked you and told you it was kind to tell someone when they had a flaw that they could fix. She added that it was unkind to comment on a flaw a person could do nothing about—for instance, if someone had spilled coffee on their blouse. You wonder what flaws you might have that no one mentions to you.

But Mrs. Burns isn’t here now. At recess she gets a break, and the teachers’ aides—Mrs. Ripley and Mrs. Gay—supervise all the second and third graders.

You are seven and on days when your mother sends you to school in a skirt and tights, the first thing you do is run so wildly across the playground that you inevitably fall and skin your knee, tearing a huge hole in your tights and turning your knee into a bloody mess (at forty, you will still have scars) so that the school nurse will sigh and say, Take your tights off so I can clean you up. And then she paints your knee with iodine and you look even more gruesome.

That’s what you want. Gruesome. Tough. Not a prim little lady in tights and Mary Janes and two barrettes holding back your hair.

Today, though, is not a skirt day. Today is jeans handed down from your brother and a blue-and-green windbreaker that you love. It is windy. And cold. You spill out of the school with the other kids, down the granite steps where every fall they line up the entire school to take a picture. Third graders on the top stair, kindergartners at the bottom. The photographer tells you all to smile. The pictures line the entry hall to the school. When the newest one is hung, other students clamor to find themselves, to see their faces looking back. You have no interest. It was enough that you were forced into a dress for the photo, enough that you pretended to look happy with your smile. You don’t need to look at someone who looks nothing like yourself.

You run past these pictures and down the steps and out onto the playground. The teachers’ aides stand near the fence that runs between the woodchip playground and the kickball field. The fence marks home-run distance. Once, Tony actually kicked the ball so hard that it went over the fence and over the tag field and hit the brick side of the school. If he had hit a window, kickball might have been banned forever. The teachers’ aides stand with their hands in their pockets, knit caps on their heads. You wear a baseball cap, New York Mets. You don’t care much about baseball, but you liked the M and you liked the blue-purple color, and your mom bought it for you last summer at a sporting goods store in Lewiston. It will show up in two years’ worth of childhood pictures, your face shadowed by the brim, and then abruptly disappear.

The third graders have already staked out their spots. No fair that they got there first. But they can’t play kickball without the second graders; there aren’t enough of them (South Paris, Maine, is small). They wait, bouncing the ball, kicking at bits of snow and ice that still edge the playground. They know that if they pick up the snow, Mrs. Ripley or Mrs. Gay will yell at them.

You stand next to Mark and Bryan. Sam has decided on tag, and you can see him arguing with the girls about what kind of tag to play. You hope you won’t be joining them. The boys at the front—Tony and Shawn and Mike and Pete—are doing rock, paper, scissors. They are the captains. They always are. There are rules and then there is what always happens.

Now they pick. They pick by pointing and saying names: Tim. (Of course.) Ricky. Jason. Mark and Bryan get picked in the middle, both for the same team. Now there are only a few of you standing, waiting to be called. You look at the two clumps of your already-chosen classmates. They are huddled around their captains, whispering. You think that Mark and Bryan are advocating for you, but you can’t know for sure. Last pick, last pick, the teams chant. Mike points at you. Alice. And there are snickers. They aren’t laughing at you, really, but at the four or five boys who are left over. He picked a girl! Instead of you!

You walk toward the team. You are careful not to smile. The four or five boys who weren’t picked shuffle off to tag, or maybe they’ll lean against the fence and watch the game and, if they think Mrs. Ripley and Mrs. Gay aren’t listening, yell rude things. This is how it works. There are always a few left over. The game is only good if some people can’t play. Sometimes you are chosen earlier. Sometimes you aren’t chosen at all. You worry about this often.

The rock, paper, scissors has also decided which team will kick first. Not yours. Everyone knows their positions. Yours is back, to the right. You like this side of the field. It is the side away from the nursing home. It has a tall wooden stockade fence and on the other side stands a dilapidated house with a mansard roof. Mrs. Burns has taught you this term, mansard, has pointed the house out and told your class that it is slated to be torn down. A loss of the town’s architectural heritage. Architecture was a spelling word. The house is still there. You aren’t entirely convinced that anything ever changes, even when adults say it will.

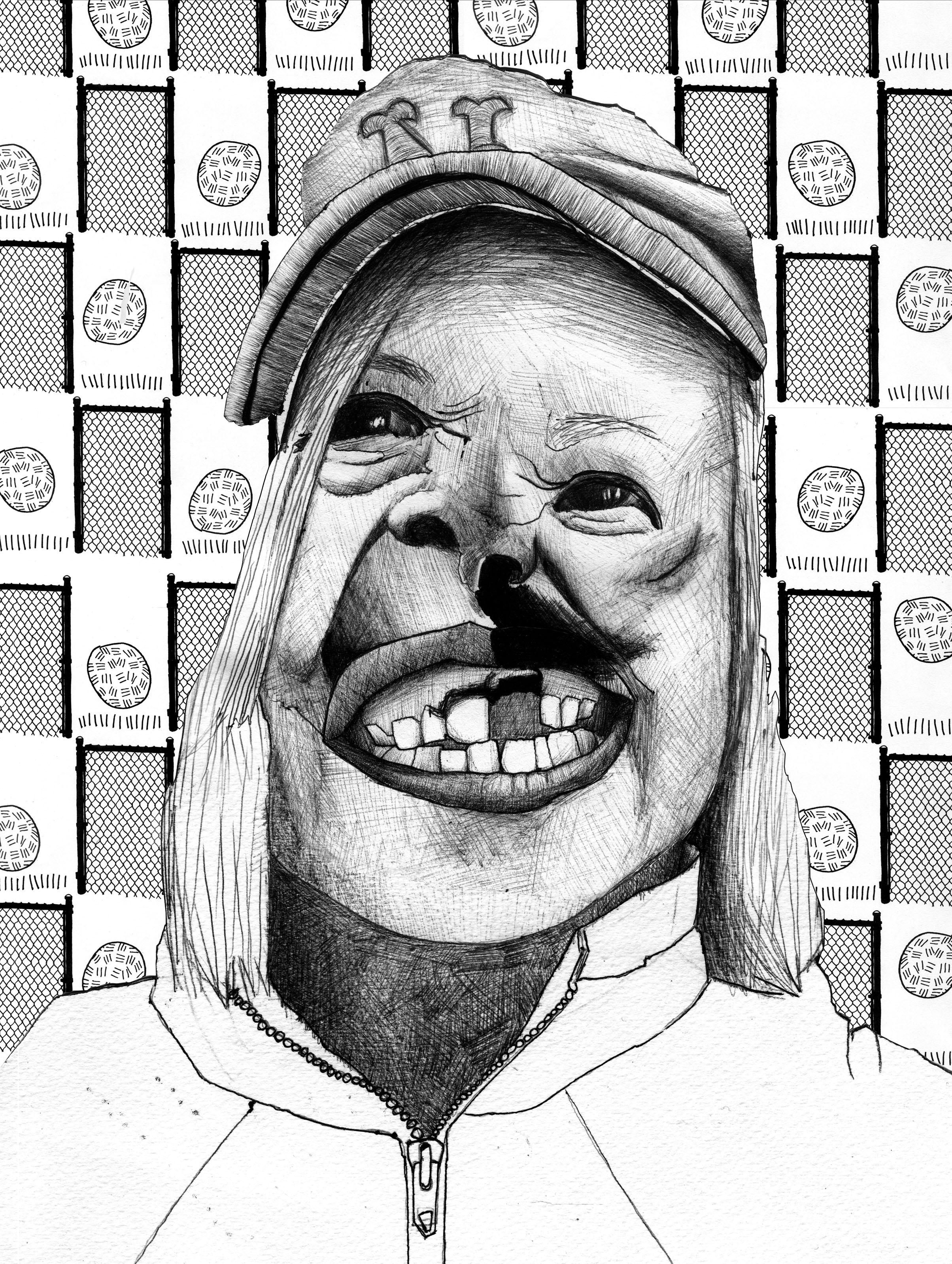

Now you shift your weight from foot to foot as the game gets underway. You do the thing you like to do—let your mind drift and imagine yourself from the outside. How do you look? From above, you look like a boy, with your baseball hat and your jeans. Someone would have to see you face-on to know you’re a girl, and even then, if you tuck your hair up, maybe they wouldn’t be sure. But you know there’s something that gives you away, and you are pretty certain it is your smile. Only girls smile like that, crinkling their eyes, tilting their heads, eager to please. You clap your hands together to keep them warm and bite your lip—a sure-fire way not to look too pleasant.

Mike stands in the middle of the diamond, pitching. He holds the red ball in two hands, up in front of his face, so that his eyes peer out over the top of the sphere, sizing up the boy who stands at home plate. Then he winds up, underhand, like he is bowling, and lets it go.

Each pitch is contested. Too much bounce, too much spin. Too wide. Once, last fall, there was such a fight over pitches that the teachers’ aides intervened and the rule ever since has been five pitches maximum. After that, it’s a walk or an out, depending. (You’re not sure depending on what.)

You look at the roof. At the tag game behind you (freeze tag, your least favorite). There are strikeouts and fouls. One hard kick down the third-base line that sends the teachers’ aides hustling for cover. Look out, look out! the boys call to them, and they put their hands over their heads and run blindly. Everyone snickers. Classic girl move. It’s just a kickball.

There’s the hard smack of foot on rubber, and an arcing shot heads out to center field. You can see boys rounding bases, and you run back and back, behind Pete, who is waiting for the ball to descend. In the event that he drops it, or misjudges it, you will be ready (as a girl should) to make the best of the situation. But he catches it against his chest and in one fluid motion hurls it to the infield. Out! Now your team hustles in.

Unlike baseball, there is no exchange of gear, no tossing of mitts, no quick striptease of catcher’s pads. There’s just the sullen jogging past, the changing of the guard. You keep your face neutral, your elbows tucked in. You’ve heard them snicker at others playing tag—runs like a girl. You wonder if that means it’s impossible for you to do otherwise. You hope you can overcome it, somehow.

Another chain-link fence borders the edge of the former parking lot, is all that separates it from the sidewalk and street. This fence is the de facto dugout, and Mike has everyone line up along it as he organizes you into kicking order. There is a science to this that you don’t quite understand. It is partially popularity, but not entirely. It is not exactly the same as being picked for the team. Sometimes he has you go second. Sometimes he has you go eighth. Sometimes you just end up at the back of the line.

Mark and Bryan aren’t talking to you now. They aren’t even talking to each other. You understand. There’s a topography here, a complex terrain. The three of you are borderline. Pulled out for a special reading group. Positioned at a small table to do math problems on your own. But you don’t walk on your toes, like Sam. And you don’t burst into tears whenever anyone calls you a name, like Greg. But still. Careful.

You set your face into studied indifference. Your gaze fixed somewhere generally near second base, where the other team huddles. You have already discovered mirrors and how useful they can be. At home, you can climb on top of the hamper and then onto the bathroom counter, to kneel awkwardly around the sink and stare at yourself. Only it’s not yourself you are staring at. You are fairly certain that you—the real you—doesn’t look anything like that girl in the mirror.

At home, you make faces. Drawing your eyebrows together, biting your cheeks in. You are trying to find the hollows and the lines of your face. You are trying to get the toughness you feel on the inside to show itself on the outside. But the outside is persistent. It is rosy cheeks and lips a perfect Cupid’s bow. It is light-brown hair that falls doggedly into your face no matter how often you tuck it behind your ears. It is a girl’s face, and it is wrong.

Now you stick your hands into the pockets of your blue-and-green windbreaker, clenching your frozen fingers into fists. Mike has put you at number six. This is, you think, a pretty good number. If you don’t kick this time, you’ll kick next time, and assuredly, there will be another inning before the bell rings.

Tony pitches for the other team. He is good at spin—pitches two-handed, to get it really going. This has been debated and deemed legal. Mark leads off and boots a double. Then Mike gets a single. Then two people strike out. Then it’s the boy ahead of you up to kick, Ricky.

The pitch comes in loaded with spin and Ricky gets his foot on it. Bip! It’s a weird nothing of a kick, but it goes forward. Lands a few feet in front of him and bounces backward, high enough to clear the fence and go into the street. There’s an eruption of noise, scrambling and yelling, and the whole outfield rushes in. Mrs. Gay and Mrs. Ripley emerge on the scene. They grab the backs of coats just like you’ve seen barn cats handle their young. Grip, shake, move aside. You stand, stalwart, on home base. You are kicking next. And no amount of hubbub is going to let someone else take your spot.

Soon enough, Mrs. Ripley has retrieved the ball, and Mrs. Gay has adjudicated the dispute. The kick is ruled a single. The bases are loaded. It is your turn to kick.

You can sense the groan. You can feel the hovering disappointment of your team. Bases loaded, two outs, and Alice is up. It doesn’t help that from the outfield Shawn yells, Girl! Girl! Move in! and the whole team takes a step, another, closer. Despite yourself, you smile. Maybe it is the cold, and you are just wincing. But maybe it is what you have been taught and told to do so often it is ingrained. Smile when you are uncomfortable. Make the person facing you think that it is all okay, no matter how much spin he puts on it.

Tony holds the ball up, then twists his torso in that strange way, winds back, releases. There’s a little bounce (you could protest) as it rolls in. You swing your leg back, hear your father’s voice, Keep your eye on the ball! (Your father, who earned only one JV letter in high school, as assistant manager of the lacrosse team.) You squint your eyes and kick. Your toe meets the rubber and sets the ball ringing.

The ball sails up. It is a beautiful thing. You watch the boys in the outfield running backward. You hear your team shouting at you. Run! Run! And you run, though you can already sense how it will happen. How the ball will rise up, swift, hopeful, how it will tremble at the top, and then tumble, inevitably, into some boy’s arms. But you run. First base, around, wide of the line, your body buoyant. Second base. You can no longer see your kick. But you hear your team erupting in shouts, indistinct at first, and then clearer. Home run! Home run!

You turn and you can see where the ball has landed and rolled across the woodchips, interrupting the tag game. This is your cue to relax into a jog and bask in your success. But the speed feels so good—the blood pounding through you, cheeks afire. You feel so fast. You hit third base, look up to where your team waits. Ricky crosses home plate. He pivots and holds out a hand to you. High five! You can’t believe it . . . the whole team is lined up, not a gauntlet to run, but a welcoming wave of slaps and cheers and you sprint to home plate and lift your hand.

The first slap stings, surprising you. The momentum of your sprint carries you forward, toward a bank of dirty snow; you put your hands out to stop yourself. Cold ice greets your palms, you slip and stumble and can’t catch yourself and you are pitching headlong toward the fence. It’s chain-link; it might hurt a bit, but it’ll give, not like running into a stone wall. But you don’t hit the four feet of meshy fencing. You hit the three inches of steel pipe. Your face explodes with the incandescence of a flashbulb. Something cracks. And you are stunned, seated in the pile of leftover snow.

Mrs. Ripley and Mrs. Gay come back. Assuredly the game is going to be ended now. The boys are yelling. You are crying, but the sort of involuntary tears that might be okay. The sort of tears that just happen and you have seen boys wipe them away, fiercely, and stand back up. That’s what you try to do now. Push yourself up. Your hands are cold, raw, red little claws that don’t even feel the icy snow. You are mad at yourself for crying.

Mrs. Ripley has your arm. Let’s get you inside. The boys fall quiet as you are led past. Tilt your head back. It’s only when she says this that you realize your nose is bleeding. It’s a line you’ve heard so often. Tilt your head back. The bloody noses from basketball, from soccer, from falling off your bike. The taste of iron in your mouth. You know to spit it out. You know how your stomach will ache if you swallow it. You are led past the tag field, along the margin of the four-square court, up the granite steps, and through the green double doors. Past the principal’s office on your left, the kindergarten classes on your right. You cannot smell the mushy wax bean scent of the hot-lunch cart.

The school nurse cleans you up. Your hands are cut (she even has to dig out a bit of gravel) and your nose won’t stop bleeding. It is 1985 and she doesn’t wear latex gloves as she sops up your blood. Hold that. Pinch tight, she tells you. You keep your head tipped back and stare at the ceiling. The blood slides down the back of your throat and you know you will be sick later. No matter. You scored a home run. That thought lets you ignore the annoying tickle of hair against your face—the strands gummy and clotted with half-dried blood.

Mrs. Burns comes in. Have a look, the nurse says as she gently touches your hand, taking the bloody tissues from you. Her mouth. Your lips have a rubbery feel. Can you open your mouth, honey? You open your mouth. Oh, Mrs. Burns says. You should call her mother. The nurse nods. What? you try to say, and as you move your lips and tongue to form this one word, you feel it . . . or, rather, you don’t feel it. Your front tooth. It’s gone.

Was it a baby tooth? the nurse asks. No. Of course not. You lost your front teeth in kindergarten, had the gap memorialized in a school photo: you in a purple snowflake sweater and a broad grin, as ordered by the photographer. Then I better call her mother.

It is just you and Mrs. Burns and the blood clotting in your nose. You lower your head. Nothing trickles out. You put your fingers to your mouth, but Mrs. Burns pulls your hand away. What? you say again, the word heavy on bruised lips, and that strange feeling against your tongue, a rough edge where a tooth used to be.

Let’s get you cleaned up, Mrs. Burns says and leads you to the back of the nurse’s office, to the bathroom that has a tub and a big sink with a mirror over it. There’s a step stool for you to stand on; it gets you high enough that you can put your hands under the faucet that Mrs. Burns has turned on, running the water to get it hot. But not high enough for you to see in the mirror.

You touch your hands to your mouth again, the rubbery lips. Can I see? you ask, the last word a lisp you’ve never had. Mrs. Burns bends down and grips you beneath the arms, hefting you in the air, the way your father did last summer when you went to the top of the Empire State Building. He’d held you up to see the whole city and your mother had issued him a warning, Douglas, as if he might let you drop, and you couldn’t believe how far the world stretched before you.

Now you look into the silvery glass. There’s a bruise blooming across one cheek, faint purple and red, with a small cut in the middle, which has oozed a fine line of crimson. You draw your swollen lips back in a fierce canine grin.

There’s a hole in your mouth. A ragged edge of tooth. You clamp down, joining your bottom teeth to your top teeth. The hole remains, a black gap all the way to your throat. You expect it to hurt, but it doesn’t. It doesn’t feel like anything.

Mrs. Burns is behind you, her reflected face worried, but you like what you see. They can fix it, she tells you. But you don’t want it fixed. The water is running hot now, steam rising up to cloud the glass, and Mrs. Burns sets you down on the step stool. Wash your face. But you don’t want to do that either.

The nurse returns and the two of them confer, leaving you to soap and scrub and rinse. You push yourself up on the edge of the porcelain sink, your arms trembling with the effort. You have to see one more time, before they come in and make you pretty again. You have to see this broken open, rough-edged, bloody person, who someday just might be you. ![]()

Alex Myers is a teacher, speaker, and writer who works with schools and other organizations to be gender inclusive. His essays have appeared in the Guardian, Slate, Salon, and Good Housekeeping, and in literary journals such as Hobart and Cutthroat. His debut novel, Revolutionary (Simon & Schuster, 2014), was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award, and his novel Continental Divide is forthcoming (December 2019) from University of New Orleans Press.

Illustration by Erin Schwinn