My husband had been beautiful once. I still remembered his beauty, held it in my mind like a tiny bird’s egg in a small child’s hands, turning it over and over, studying it from all sides: the cleft in his chin, his thick ebony hair, his lean muscles, the way I’d lay my head on his bare Jim Morrison chest, the way he looked at me, like the most vulnerable man-child on the cover of Tiger Beat, circa 1979. That was five years ago. Now he was twenty-three, twenty-four. It wasn’t that he was no longer beautiful. But there was something lacking, a noticeable void, a terrific vacancy. I could no longer remember the last time we’d made love, the last time he’d pulled hair from his head over a fight with me. We’d had a child; this was one thing. There was a collection of unopened pharmaceutical bottles on the kitchen counter with my husband’s name on them, another.

My husband had a morbid fear of flying. I dropped him off on the curb at the Detroit airport at four in the afternoon anyway, the kid in her car seat behind me. “Say goodbye to Daddy,” I advised her. The back window was rolled down, her daddy standing uncertainly with his backpack on the corner as men full of certainty and much more strolled by him on either side. He’d been saving for this trip for six months, squirreling away extra money we didn’t have from his paychecks when he still got them. I’d spent the last eight weeks helping him get his passport at the post office, his passport photo taken at Walgreens, traveler’s checks at the bank; I checked out travel books for him from the library, called Delta to reserve his ticket. We didn’t have computers or cell phones, then. This was before Y2K, before he started stockpiling bags of beans and rice around the bedroom or bought a sleeping bag from the army surplus store that could tolerate extreme cold temperatures. I never asked why he bought only the one; what he expected Skylar and me to do when the heat went out in the middle of winter, on January 1, 2000. Maybe he thought we would all cram into that one army sleeping bag. I didn’t know how to tell him I didn’t feel that way anymore, though maybe I would if survival was the imperative. I’ve heard the body is capable of strange adaptations in strange conditions, perhaps even sharing a bed, or a sleeping bag, with the father of your only child during the end of times.

But like I said, that was all still a year off. It was finally 1999, just like the song we’d been singing since 1983 foretold. And I’d met a woman. A beautiful woman, as they always are, or seem to be, in stories such as this. But I’ll get to her in a minute. First we had to say goodbye to Skylar’s daddy.

Skylar waved and shouted, “Bye, Dad!” and went back to the sticker book I’d bought specifically for this car ride. I’d let him name her even though I thought the name sounded like a stripper’s. Maybe it was also the name of a rock star’s child who had died, terribly young, of some terrible disease. I didn’t like to think of that either. I was accumulating things I didn’t like to think about, did my best to avoid, to push to the back of my brain. I envisioned a closet somewhere back there, filled with unwanted memories and terrible thoughts of the future. I closed and locked the door in my mind. I deadbolted that motherfucker. It didn’t always work. Sometimes the thoughts got to the front anyway. But what can you do? Not much, I was learning. I was thirty. Someone’s mother, someone’s wife. All the things I always knew I’d be. I always knew I’d be divorced, too, but I didn’t want to talk about that just yet.

We were liberated then, without laptops and cell phones, liberated in ways you’ll never know, in ways even we didn’t realize. Once I left that airport roundabout I was free! There was no way anyone could reach me. So long as I remained in the car. So long as I kept moving. I could drive across America! Lost! My husband was never going to get on that plane. But maybe for the night I could pretend he would. Katarina was due to arrive in three hours. I got back on the freeway in a jiffy. I didn’t give another thought to my husband and his fear of flying. I’d done everything I could. I couldn’t hand him courage like I was the Wizard of Oz or something, could I? I didn’t have that power, or believe me, I would have. I could have used ten whole days. I could have used longer. The part of me that thought he might fly to Amsterdam on account of pot being semi-legal there wondered if he’d ever make it back if he did. Maybe, I thought, he’d wander around the Netherlands the rest of his life, backpack over his shoulder, hashish in his pocket, uncertain, but high, uncertain and even more paranoid, too paranoid to fly back to America . . . I know it was wrong of me to think this way, to drop him off at an airport, unaccompanied. But you try living with a man like my husband for six years. Claustrophobia was the least of it. You have no idea. There were all those maps covering the kitchen walls every spring, the prolonged monologues at dinner, the accusations of my having hired a hit man or, more specifically, a mob of local teenagers (“It’d be easier than a divorce”), the standing on the curb out in front of our house at dusk to chide and to count passing cars, acquaintances of ours, my husband’s boss and coworkers, neighbors . . . You really don’t know.

I’d met Katarina at the chain bookstore in Flint. She was their Storytime woman then. Every Thursday at eleven, Skylar and I sat in the front row—me cross-legged, Skylar on my lap. All the other children ran around in circles, chasing each other. I never saw any of them sitting on their mothers’ laps. Skylar didn’t care for other children and she really didn’t care for Katarina’s daughter, Tuesday. (I couldn’t blame her. Tuesday was only three and seemed to already have an eating disorder; every lunch we shared with them turned into a battle of wills between Katarina and Tuesday to see if Tuesday would take a single bite of cheese pizza.) This might have posed a problem (for me) had Katarina noticed, but part of Katarina’s charm was her obliviousness to all things negative (aside from her daughter’s eating habits). She existed in a bubble of positivity. I thought maybe it was her green Adidas track pants. They were hip and youthful (in 1999) and perfectly fit her ass. She had a wide ass and a tiny, narrow waist, which only accentuated her wide ass. I tried not to stare at it. Or, I tried not to let Katarina catch me staring at it. But, like I said, she was mostly oblivious. I don’t think she ever noticed. I only looked two times each Thursday: once at the beginning of Storytime, when she invariably strolled in late, Tuesday in tow, whining or crying; and at the end, when we left the bookstore together to grab lunch, the other moms jealously watching our exit.

How we had come to eat lunches together I don’t know. Or I don’t remember. Just one day we did and then every Thursday after that we did, also. Sometimes Katarina invited another mom and her kids. Rarely, two other moms. I sort of resented when she did, but, of course, I did my best to hide my resentment. After all, she’d been nice enough to invite me and I was a loser with no friends. We’d only moved to Flint when I got pregnant, an escape from my in-laws’ basement. Beggars can’t be choosers, as they say. And I seemed to always be begging in life: begging for my innocence and begging to get a word in and begging for a few minutes alone; begging, begging, begging. I would have begged for Katarina’s friendship in a heartbeat, but I never had to. That was the great thing about Katarina, she just gave herself to you. She just asked you out to lunch one day and then you were great friends. I even bought a pair of Adidas track pants. Of course I avoided green, even if secretly they were the ones I most wanted. I bought the navy. Wore them to Storytime. Wore them around the house. My husband didn’t stare at my ass in them. I’d never had a great ass. My ass was where I was lacking. I had a typical white-girl ass, flat as a pancake. Maybe that’s what attracted me to Katarina. Maybe we’re attracted to in others what we lack ourselves. As soon as I got home from the airport, I called Katarina. “Everything’s a go,” I said. I was holding Skylar on my hip. “See you at seven?”

I’d had to invite this other mom, too—Kendra, a friend of Katarina’s who was now also, it seemed, a friend of mine—so that it didn’t seem weird, like a date or creepy or whatever. I didn’t really know how Katarina felt about me. I only, of course, knew how I felt about her. I wrote her name in my journal over and over. All caps. All lowercase. Hers and mine together. Hearts everywhere. I was mad about her. Her ass and her blond hair. I loved her hustle, too. She was a single mom, six years younger than me. She had a whole series of freelance jobs: yoga, kickboxing, massage, the Storytime gig, selling Tupperware, selling Avon. You name it. She lived in her childhood home, a tiny two-bedroom ranch, in Swartz Creek, ten miles from the Flint mall. She’d been in a horrific car accident when she was sixteen; her father, brother, and grandmother had all been killed in that accident. Only Katarina and her mother survived. Katarina had been driving, but it wasn’t her fault. A semi truck crossed the center lane, hit them head on. There was nothing sixteen-year-old Katarina could have done. Her father was in the passenger seat. There was nothing he could have done either. A strange woman ran to her at the site of the crash, took her in her arms. It was with some of the money the state gave her that she bought her childhood home. We stood in her childhood bedroom once—it was now Tuesday’s room—Katarina showing me the closet where she stashed all the peanut butter and honey sandwiches she didn’t want to eat as a child. “They were turning blue with mold in Ziploc baggies when my mother finally found them,” she said, giving me her full-teeth grin. I wanted to slide down her track pants with my mouth when she grinned at me like that. Of course I never told her what I wanted. She had a boyfriend named Ryan who chain-smoked cigarettes and talked her into having threesomes every other weekend. She’d tell me about them later, at lunch at Chuck E. Cheese on Thursday. I’d listen carefully, imagining myself in the role of the new girl: sucking Ryan’s cock, gone down on by Katarina. I kept waiting for her to ask me. I figured I’d say no out of fear and on account of my being married, but I was desperate for her to ask, at least. I wouldn’t have minded Ryan’s dick in my mouth either. He was charming in the way men who beat their wives are charming. I’m not saying he beat Katarina; in fact, I’m pretty certain he didn’t, but he had that cocky swagger men who beat their wives have, and I couldn’t help being taken in by it. But mostly I was taken in by Katarina. I hoped she’d be wearing her green track pants when she came over. I brushed my teeth carefully, stepped into a new pair of underwear, wore a sundress. My hair was long. I had that going for me. Long, virginal hair. Someone had told me a few years back that I looked like Tawny Kitaen, the woman slithering around the car in the Whitesnake video. I figured it was the hair. Mine was auburn and long—cascading, if you will—like hers. It was a friend of my husband’s who told me that, right in front of my husband. We were all sitting around the friend’s living room watching MTV and smoking dope. We never saw that friend again, never sat in his living room or smoked his dope again either. My husband was like that. He would have been jealous of Katarina, too, if he’d ever met her. The second he’d started talking about the Amsterdam trip I’d started plotting inviting Katarina over. Luckily, I had the foresight to invite her for the first night, the night of his departure. I probably always knew it would be my only opportunity. I only ever saw her at lunch, on Thursdays.

Fifteen minutes till seven, the phone rang. I had to answer it in case it was Katarina. Maybe she needed better directions. Maybe she was running late.

“Hello?” I said. I was holding my breath. I was praying for a better outcome than the one I knew I deserved. Skylar was at the table coloring a T. rex. Purple, instead of brown or green, but who was I to point this out to her. Fucking Barney.

“I can’t do it,” my husband said. He sounded out of breath. He was panting and it sounded like he was pacing, moving about whatever distance the airport pay-phone cord was from the wall.

“Well, I’m not coming to get you now,” I said. I didn’t add “sorry.” I thought about it, but it wouldn’t have felt genuine. “I told you so” would have felt genuine, but bitchy. I hated sounding bitchy.

“You should have seen the way she looked at me,” my husband said.

“Who looked at you?” I asked, even though I knew it didn’t matter. Someone was always looking at him funny. It was why he’d had five different jobs in two years: house painter, dishwasher, grill cook, maintenance man, a short-lived job at the DNR. Things always started out fine and then slowly the men he worked with would start talking about him—behind his back at first, then right in front of him, plotting his demise or death, or worse. I guess the men were like me in that regard. I guess things were accelerated in airports, regarding international travel. Plots to demise my husband, I mean.

“The airline lady at the desk. Both of them. Everyone at that airline. I couldn’t get on the plane, the way they were looking at me. I knew what they had in store.”

I sighed. Not audibly. To myself. Inwardly. Sometimes you’re not a nice person. Sometimes you’re not the hero People magazine and Oprah want you to be.

“Well, I can’t come get you right now,” I repeated. I hated being the bitch but one day in six years I figured was okay.

“Can you be here in the morning? I’ll just walk around. I’ll just sleep on the sidewalk. I couldn’t get on that plane. You don’t know what they were prepared to do with me. I could see it in their eyes. I’ll be lucky if I’m still here in the morning.”

“Yeah, I’ll be there in the morning,” I said, sighing again, this time audibly.

“Okay,” he said. “Can you be here around nine or ten? I’ll just be walking around. I can use my backpack as a pillow. I can eat the sunflower seeds I packed for the flight.”

He was constantly seeing himself as the martyr like that, too. I guess it’s why he didn’t notice my sighing.

“Yeah,” I said. “I’ll be there at ten,” I said. And I hung up. I didn’t wait for a goodbye. I only had eight more minutes until Katarina was due to arrive. I went in the bathroom and brushed my teeth again, thought about the last threesome Katarina had described to me; something about red leather lingerie and a dog collar and a chain. Once, my husband had asked me to humiliate him, sexually. I’d squatted over him in a camisole, the camisole gathered up around my hips, urinated on his chest. It still looked like Jim Morrison’s then. I pretended I was peeing on the late Doors’ singer. I drank a lot of water first. I chugged and chugged glasses of water until it was such a relief to feel the pee streaming out of me, warm and heavy, I almost came. I did come a few minutes later, Jim Morrison shoved inside of me. Jim Morrison practically sobbing as he came, too. His hair was a tangled mess. His forehead flushed and sweaty. A bead of Jim Morrison’s sweat dropped in my eye. The lizard king, his cock deflating, wet and warm, like I imagined it inside those leather pants.

It’d been a long time since I could look at my husband and see Jim Morrison. Lately, all I saw was fear and paranoia. Maybe that was part of Jim Morrison, too. But it wasn’t the sexy part, the part anyone wanted to look at. It was the part in the bathtub in Paris at the end, bloated, ugly. I was drawn to the dark parts, initially, and then I was repelled by them. I wanted to run from the dark parts now, like in a Doors’ video they never released. “Riders on the Storm.” I heard that song in my head all the time now when looking at my husband. I asked if he wanted to take a bath. He only ever took showers. My luck. Anyway, we weren’t in Paris. We were somewhere in bumfuck Egypt. Small town, Michigan. A teeny tiny town just south of Flint where the middle-class and poor white people lived next to Kmarts and Dairy Queens. There was a Little Caesars down the street. It was the only restaurant food my husband would eat. He didn’t trust any other fast-food place. I guess it was on account of how he’d worked at a Little Caesars once, in his youth. But that didn’t make sense to me, either, because he’d told me how he’d pissed on this guy’s pizza once after the guy was a dick to him on the phone. But I’d stopped trying to make sense of things a while ago. I just nodded and ordered Little Caesars. What the fuck did I care what pizza we ate? I didn’t like pizza anyway. I only ever ate the crust. I figured the piss wouldn’t make it past the cheese.

Katarina and Kendra arrived together, in Kendra’s minivan. I was hoping this wouldn’t happen, that they would drive separately, Katarina in her black Saturn (tan interior), even if I knew that didn’t make sense. Economically, I mean. Fuel-wise. Katarina was frugal. She had to be, on account of being a single mom with a douchebag boyfriend and all. I don’t know where Ryan worked but I knew he didn’t make much money. And what he did make went mainly to the purchase of tobacco and beer, occasionally cocaine. Another reason I was attracted to him. I had a thing for redneck assholes on account of my childhood in Ohio. My husband was more poor white trash. I had a thing for them, too. Gummo made me horny. Katarina bore a resemblance to Chloë Sevigny, an actress in that movie. You could make a case for Katarina being poor white trash like me. All of us Chloë Sevignys.

Katarina wasn’t wearing her green track pants when she arrived. Katarina was wearing a sundress, too. I tried not to show my disappointment. Anyway, the dress clung to her ass in a way I hadn’t expected until the first time she turned around. It was a pleasant surprise. I thought, hey, this night might still be okay, after all. Then Kendra walked in the house and I wasn’t so sure. Kendra had a habit of talking about her son’s penis. Her son was two. Apparently his little penis got boners, though. I hated hearing about it. Once, at an outdoor concert, she’d been going on and on about it and a guy next to us had said, “Hey, if you’re just going to chatter all night, why don’t you go sit in your car in the parking lot? Some of us are here to hear James Taylor sing.” I thought it was a decent question. I was curious about the answer myself. Not because I care that much about James Taylor—oh, he was all right, though at this point he’d already sung the fire and rain song—but because I, too, was bored of hearing Kendra’s stories about her son’s penis. But Kendra didn’t answer it. Kendra told the man to go fuck himself, that this was a free country and she’d paid for her ticket same as him. Kendra didn’t have a nice ass. Kendra had a fat ass, but Kendra was fat all over, so it didn’t make much difference. Kendra also had a bad perm, even by 1999 standards. Kendra was what my grandpa would have referred to as “uncouth.” I guess what I mean by that is she was loud and fat and vulgar. Also, she had four kids all under the age of five. It was a lot to go anywhere with her, on account of her vulgarity and all those kids. But Katarina seemed to like her, so I had to pretend to like her, too.

“Hi,” I said, smiling my best fake smile.

“Hey,” Kendra said. “Nice place.” I could tell she thought it was a dump, that she was lying like me. It was an old, plain farmhouse. There wasn’t anything nice about it other than that we lived in it. “Nice backyard,” she added, looking out the kitchen window. The backyard was nice, I’d give her that. It was two-tiered and led down to a river. You had to be careful on account of accidental child drownings, but other than that, it was a great yard. My husband had even scraped out a fire pit, lugged some rocks around it, in better times. Katarina had said last time we went to lunch she could start a fire on account of having been in the Girl Scouts for many years. I was eager to see. I couldn’t light a match without burning my fingers or catching my hair on fire. I’d never been in the Girl Scouts on account of their God oath and on account of my mom being a nonconformist and a hippie.

“I brought marshmallows,” Kendra said, tossing a bag I noticed was missing the Kraft logo on the counter. There were only a few food products that mattered, as far as brands, and as far as I was concerned, marshmallows were one of them. Also, mayonnaise, toothpaste, and ketchup. All the condiments, really. Her four kids were running around us in the kitchen. Well, that baby was in one of those plastic carrying cases like for baby dolls. He could have been an actual baby doll in that thing; I wouldn’t have been able to tell the difference, as much as she didn’t tend to him. Skylar sat watching all those kids, Tuesday among them, falling on their asses, headbutting the walls and each other. Skylar couldn’t ever understand why Mommy invited them over. In her narcissistic three-year-old mind she must have thought I’d done it for her, which must have confused her since she knew I knew she didn’t like any of these children. I couldn’t explain to her that Mommy was ignoring her wants for a night because Mommy had the hots for Tuesday’s mommy; Mommy wanted to scissor with her or whatever lesbians did together, I wasn’t really sure. I only knew what I’d seen on South Park. I knew it wasn’t accurate but I didn’t have anything else to go on. Movies like Henry & June always cut away before any real sex happened between two women.

“I brought wine coolers,” Katarina was saying. “Who wants one?”

I was up for scissoring or whatever Katarina wanted to do, sexually or erotically speaking. But there were all these children in the way, and even if they magically all fell asleep at the same time, like with some sort of pixie dust, there was Kendra to contend with. Big, loud, penis-envying Kendra. I was beginning to loathe her. But there was nothing I could do about it. It was a free country, wasn’t it, and Kendra had bought her ticket just like the rest of us, hadn’t she. She was a friend of Katarina’s also and she had every right to be here.

Just to prove as much, Kendra raised her hand and Katarina handed her a wine cooler. Something berry. They were always something berry. In high school they’d come in two liters like pop and we drank them right out of the bottle (unlike pop). I associated drinking wine coolers with throwing up in the passenger seat of a friend’s car, the quarterback of our football team in the back with our sluttiest friend, Sissy. He was probably about to finger Sissy when I retched. That was probably why she was so pissed at me Monday morning. The vomit had little bits of Kraft Macaroni & Cheese—another important food brand—in it. Kendra was already done with her first wine cooler by the time I opened mine.

“I’ll just pump and dump,” she said to no one in particular.

It’d been four or five years since I’d had anything alcoholic. At a recent wedding I hadn’t even sipped the champagne during the champagne toast. I was trying to be supportive of my husband. I was also always trying to outrun my childhood, my scotch- and gin-filled lineage. But I would have done anything, short of heroin, and maybe even that, as long as we didn’t inject it, for or with Katarina. As luck would have it, though, she’d only brought the wine coolers. There was no need to test my willingness or unwillingness to do narcotics with or for her.

“Drink up, friend,” Katarina said, squeezing into the kitchen chair beside me, clinking together our bottles. I could have passed out from the intimacy of her hip pushed against mine. I needed the alcohol now. It wasn’t just for show. I took a long drink, then took another. I belched, but quietly, with my mouth closed.

“Excuse me,” I meant to say, but the words mostly came out in giggles. I hadn’t noticed before but it looked like Katarina’s hair was newly bleached. It seemed to shine in the stark kitchen light. Or gleam. Maybe it gleamed.

“Guess what I brought us?” Katarina said, fishing in her dress pocket for something. If she were a man, I would have guessed condom. As it was, she pulled out a pack of clove cigarettes.

“For later,” she whispered to me. “When we have a fire. The kids won’t notice that way. Everyone will smell like smoke.”

Where was Kendra during all of this, our most intimate moments? Maybe outside with the kids. Maybe in the bathroom. Who knows. Who cares. This was my first time alone with Katarina. This is why I am telling you. It was already worth everything: the post office, Walgreen’s, the library, calling Delta, the drive to the airport . . . It was already worth more than I could have predicted. Sharing that kitchen chair with Katarina. It was hard to remember an intimacy such as this with a man. It was already hard to remember anything else.

We made the kids hot dogs, boiling them on the stovetop, filled their plates with potato chips and green Jell-O. Midwestern slop. They sat on the living room floor with their paper plates, eyes glazed, watching cartoons on TV. Skylar, by this time, had acclimated to the group. It always took her an hour or two and then she could be like them. She sat on her splayed knees next to Tuesday. One of Kendra’s sons, I could never remember who was who—Logan or Cole or Kenny, sat on the other side of her. I noticed when I glanced in the living room that he was pulling at his crotch. Probably has a boner, I thought. I wondered if I should alert Kendra, if she’d want to take note of it, commend him or something. The generic marshmallows were still lying on the counter. We’d polished off five of the wine coolers. The sixth stood unopened in the cardboard carrier. Katarina must have noticed me staring.

“I believe you’re the one lagging behind,” Katarina said, handing me the bottle. Then she sat in the chair next to me and I was gone again. Opening the bottle, feeling Katarina’s thigh this time, swallowing a mouthful of the malted beverage that was meant to taste like berries. All I tasted was alcohol and fizz. Sweat concentrated between our legs. I wondered if Kendra was jealous, but she was off telling the kids something to do. This seemed to be what she was best at: dictating the behavior of small children.

The phone rang and I didn’t get up. And not just because Katarina’s thigh was still pressed firmly against mine.

“Aren’t you going to answer it?” Katarina asked.

“No, I don’t think so,” I said.

“Why not? I always answer mine. If it’s a sales call I just tell them to go to hell,” Kendra said, peeking her head back in the kitchen.

“I just don’t feel like talking to anyone,” I said, holding up the bottle as though we were actual teenagers left home alone, drunk, and it might be one of our parents calling.

“I’ll get it,” Kendra said, walking toward the phone.

“No!” I yelled. “No, no, thanks, don’t worry about it. They’ll call back, whoever it is,” I said. “Why don’t we go out and start the fire anyway? It’s getting dark. It’ll be easier if we start before it’s dark.”

Kendra stood, frozen on a kitchen tile halfway to the phone. I knew her stance was one taken to make me seem crazy.

“Okay, friend, whatever you want. It’s your house. You’re calling the shots tonight,” Katarina said. “Come on, kids. Who wants s’mores? Who wants to watch me start a fire?”

I grabbed the bag of marshmallows and some matches, the wine cooler. I stared at Katarina’s ass as we exited the house. I think Kendra caught me staring. She looked at me funny. I think. It’s hard to tell, really, since she always seems to be looking funny at one thing or another. Maybe it was just her face. Anyway, I stared at Katarina’s ass all the way down to the riverbank. I’d stopped giving a shit about Kendra. Maybe it was the wine coolers. Maybe it was just life.

The last time I’d allowed my daughter to have a playdate at our house, things hadn’t gone so well. My husband had stayed home from work, claiming he was sick. Or maybe he’d lost another job. I can’t remember. Either way, he was home and our daughter’s friend was on her way over and moms and children always seemed to be scared of my husband. Maybe it was the long, ungroomed hair and beard. Maybe it was the dark, darting eyes. Or the way he gestured a lot with his hands when he talked—not in the usual way but the way Brad Pitt gestures in 12 Monkeys—or how he could talk seemingly without a break for five minutes straight about any topic, though he always seemed to come back to one conspiracy theory or another. To be honest, I slept with a flashlight and the phone in my hand some nights. There wasn’t anything specific I was afraid of. But that’s the thing, it’s usually the unspecified we fear the most, isn’t it?

“Can you just, like, wait in the basement while they’re here?” I’d heard myself asking him that morning. It was another horrible behavior on my part. Right out of a nineteenth-century novel. I was the husband hiding my wife up in the attic. Only we didn’t have an attic. Or if we did, I’d never seen it and I didn’t know how to get up there. My husband hung out in the basement a lot even when I wasn’t hiding him away from skittish, Midwestern moms. This was my reasoning. It wasn’t really that bad a thing to ask. Only toward the end of the playdate, when the four of us were seated at the kitchen table, directly over where I knew my husband was likely standing in the basement, did I feel really bad. I had made another recipe from the Winnie-the-Pooh cookbook he’d gotten me for my birthday or Christmas, I can’t remember: honey cake. I made sure to save some for my husband to eat when he came up. I saved him a nice big piece with plenty of confectioners’ sugar still on top even though he barely ever ate. Even though he’d recently lost twenty pounds on a diet of mostly coffee and cigarettes. Even though he hardly slept now either.

If the phone rang while we were down at the far edge of the yard by the river, I didn’t hear it. That was the point. I wasn’t driving an hour and a half to the airport now that it was nighttime. Anyway, I’d had the wine cooler and a half. Anyway, we’d spent two months preparing him for this trip to Amsterdam, not to mention how much the ticket cost, and I should get at least one night out of it, right? Most of me thought that was right. The other, smaller part of me I silenced with more wine cooler. Berry-flavored. This time I could taste the berry.

Katarina wasn’t bullshitting; she could really start a fire. She wasn’t as fast or deft as my husband, who hadn’t learned so much in the Boy Scouts as with his dirtbag friends in his juvenile delinquent years, stealing golf balls from the golf course and selling them back to golfers, eating crayfish raw from the river, and starting campfires rather than going home at night, a little suburban Huck Finn. But something about the seriousness of Katarina’s face as she fiddled with the newspaper and sticks struck me. It was similar to how my husband had seduced me all those years earlier, building a fire in a Minnesota campground, impressing me with his knowledge of local edible plants and fungi, as though we might really live in a forest, make a home of fire and weeds. Katarina hadn’t mentioned anything about fungi but I didn’t care much for mushrooms anyway. I really only liked fire. I sat in one of the folding chairs, Skylar on my lap, marshmallow-pierced stick in her hand, staring at the bright glow that was Katarina’s newly bleached hair radiated by fire. I couldn’t help missing those green track pants. Maybe I had developed a fetish for them. I couldn’t be certain if it was the Adidas brand or the nylon or that specific shade of green. I thought about buying a pair, keeping them stashed secretly in a drawer, putting them on when I was alone . . . or of stealing Katarina’s pair sometime when Skylar and I were at her house, when she was busy with the kids, but how would I get them out of there? A pair of Adidas track pants were a good deal bigger than a pair of ladies’ underwear, for instance. I guess that’s why men always seemed to steal women’s lingerie; it was so easy to confiscate, to get out the door. But probably I’d miss seeing her in them. More than I’d get any sort of sexual satisfaction or erotic pleasure out of having them, I mean. Even if they were in her dirty clothes pile and thus, ostensibly, would have her scent on them, in the crotch area, I mean. Men and women are just different that way, I guess. When it comes to getting off smelling crotches, even if, admittedly, I liked the smell of my own and went out of my way on occasion to smell it.

The kids were getting sleepy. Or that’s what Kendra said anyway. “I’m going to take them inside, put in a movie. I brought The Little Mermaid with me. You’d be surprised how much boys love The Little Mermaid,” she said. She said this in a way that indicated she thought it was indicative of her sons’ heterosexuality. She said it with a wink, I mean. Like they had the hots for Ariel. Not that they wanted to be Ariel.

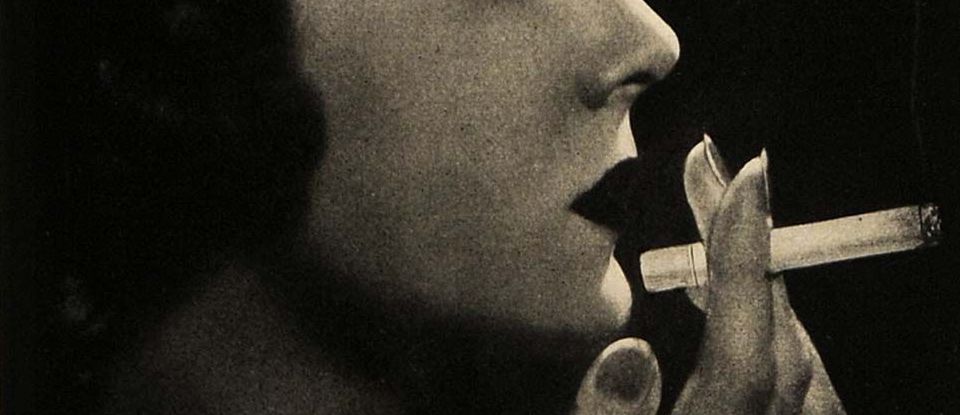

Katarina didn’t waste any time. She came and squeezed her fat ass into the folding chair beside me. “Want one, friend?” she said, shaking out two clove cigarettes from the pack for us. “Sure,” I said. I hadn’t smoked in five or six years, either. But these weren’t real cigarettes anyway. They were worse for you than real cigarettes. Someone on the radio had said that. But what did I care. Something has to kill you. Might as well be a goddamn clove cigarette. Might as well be Katarina Smitz.

We sat like that a long while, smoking our clove cigarettes, our bodies smushed together like girls sharing a sleeping bag at a slumber party. The clove had a pleasant smell, especially when mixed with the fire. I could have turned my face at any moment toward Katarina’s. This was what I was thinking the whole time we sat there. But I never did. I never did turn it. And now I wonder how many moments in my life I’ve wasted in not turning my head. Though I don’t consider those moments wasted either. I consider those moments—those before Kendra returned to the fire with us, those when Katarina and I were in perfect symmetry beside one another, like the two women on the cover of that Jane’s Addiction album, one leg bent up each, foot on chair, one arm bent at the elbow to better bring the cigarettes to our mouths—a kind of song I will always sing. I don’t remember how long Katarina and I sat there like that. The silence was something else we shared; lyrics I’ll never forget. By the time Kendra arrived, to be honest, it was a relief. I couldn’t have endured any more of that tension without biting something—myself, most likely. I might have bitten my arm or hand, or burned one or the other with the clove cigarette, had Kendra not arrived when she did, carrying a bag of Doritos, that funny look on her face. It was such a relief to see Kendra. I never thought she would be such a relief.

My husband was on the same curb where I’d dropped him less than twenty-four hours earlier. I could see him doing the Brad Pitt gesturing as I neared. I pulled the car over and unlocked the door, popped the trunk. I tried to catch my breath. It was shallower now. My stomach was something like dead weight, also. My husband got in the car beside me. He was mid-monologue but I wasn’t listening. I’d heard it all before. He smelled of patchouli and tobacco and coffee. Mostly he smelled of stale, uncirculated air. I wondered if I smelled of clove and campfire, if he would recognize Katarina’s scent on me. But he barely seemed to notice me at all. He didn’t notice, for instance, that I was wearing my Adidas track pants. He was concentrating on the sights of the airport, the planes, mostly. I knew he was waiting for one or two to fall from the sky. I knew because he was telling me this. I’ve chosen to mute him here at the end of the story. I’m omitting the vast majority of his dialogue, his unkempt hair and wild eyes, too.

Skylar was in the back seat with her sticker book. “Hi, Dad,” she said very nonchalantly, as though this were her father’s job, as though we were picking him up routinely from work.

“Hi, kid,” he managed, turning momentarily toward her. And I pulled out into traffic. I merged with the other moms and dads on the freeway; other families just like ours. ![]()

Elizabeth Ellen is the author of the story collections Fast Machine and Saul Stories, the novel Person/a, and the poetry collection Elizabeth Ellen. She is the founder and editor of Short Flight/Long Drive Books and lives in Ann Arbor.