Pain Is the Awareness of Being Alive | An Interview with Lina Meruane

Interviews

By Megan McDowell

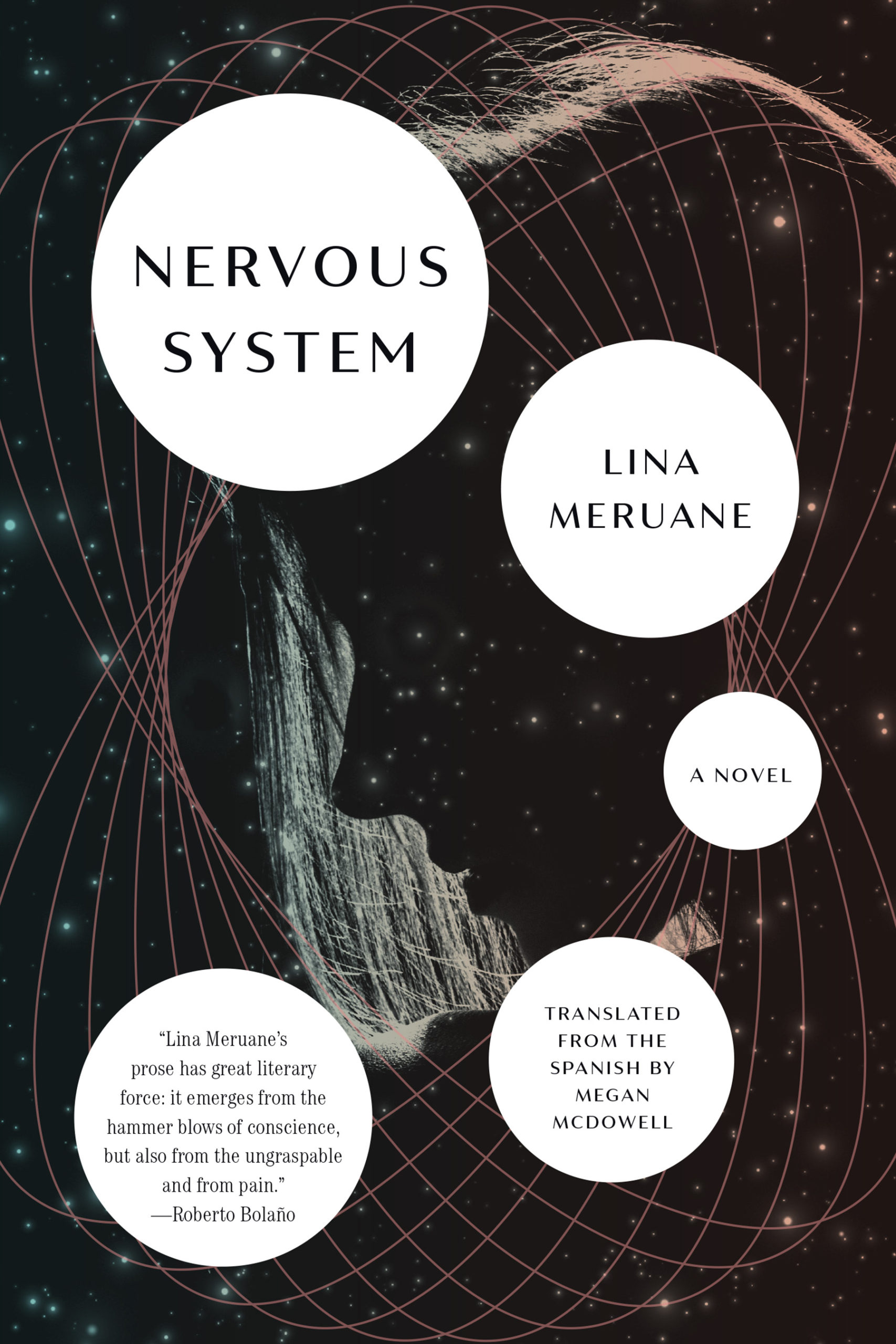

Lina Meruane doesn’t shy away from difficult subjects. Her nonfiction includes a diatribe against having children and a profound reflection on returning to her Palestinian roots; her fiction often gets up close and personal with the human body in all its frailty and fallibility, its visceral materiality. I’ve had the good fortune to translate two of her novels: Seeing Red, whose main character suffers a hemorrhage in her eye and has to deal with the possibility of going blind; and Nervous System, just out from Graywolf Press.

Nervous System is a clinical biography of a family. Ella is a would-be astrophysicist, if only she could finish her dissertation; El, her partner, studies the human remains found at mass grave sites. Ella’s father and stepmother are both doctors. Her older brother is an exercise addict whose bones break with alarming frequency. All these characters have dedicated chapters that bring them into focus through the lens of their illnesses or trauma. From that intimate view, the narrative spirals out to include other systems—family, the state, the stars—in a story that takes place on various levels and pushes the limits of story itself.

As in all her writings, Lina excels at finding meaningful, sometimes jarring images and sitting with them, prodding them the way you do a wound to see what sensations arise. Her prose is rhythmic, almost self-aware, and manages to interweave the clinical and the poetic with startling finesse. I got the chance to talk with Lina about her book now that it’s out in the world—a very different world than the one in which it was written, but one where it resonates deeply.

Megan McDowell: Each section of the book focuses on a different character: Ella, our protagonist; El, her boyfriend; and various members of Ella’s family. As we shift our focus among them, we also move around geographically and in time, and each chapter has a time-based subtitle. Ella’s chapter, for example, set mostly in New York City, takes place in “the restless present.” The Mother’s section, set mostly in Chile, occupies the “past imperfect.” And so on. I feel like this is an ingenious way of signaling how time functions in the book—it’s slippery and imperfect and we’re going to skip around. Can you talk a little about your decision to include those subtitles, and how you think of time in the book? Also, I love how you refer to the US as “the country of the present” and Chile as “the country of the past.” Is that how you think of them in your own life?

Lina Meruane: As I was writing this novel, Ella—whose professional identity and trajectory was unknown to me at the start—“became” an astrophysicist and I began reading astrophysics. I fell in love with this scientific but also conjectural and poetic discipline, and discovered that in the cosmos, time and space cannot be measured or even reasoned about in the way we know. Time and space are not so distinguishable in the cosmos, or, perhaps, distance is turned into time and time into distance. This is a complex idea, but I thought maybe I could work from this notion and at least complicate the linearity of time. I wrote many episodes as if they were occurring simultaneously, or replaying constantly, and realized that we live in and by our past so much. Or I wrote about Ella watching the stars at night and realizing they may not be there at all—that the stars she watches in the present might have extinguished centuries ago even though they still constitute her present. I’m not sure “blurriness” is the word to describe this sense of simultaneity. Perhaps it is, perhaps not; in any case, I realized that working with time in this way might be hard to grasp, so I left signals in the subtitles to alert the reader that time follows different rules in this book. I also connected places with the past and the present only to undo this later. Ella’s Chile is in the past while it is also determining her present attitudes, her subjectivity (the past is alive in her), and the US is only the present while she is there, but she is moving back and forth in body and soul, so the US easily becomes the past. I guess that’s how I feel about the places I live in. I carry them; they exist in me in simultaneity. I never feel I am away from Chile or away from the US, even if I’m in Palestine or Germany! I’ve just moved next door, but I still care about what has happened and continues to happen in those places. Don’t you also feel that way?

MM: Definitely! It’s weird, I feel like the US is my political world (I still listen to a lot of US news) and Chile is my literary world (I read much more literature from Chile and Latin America), and I’m very much in both of them at the same time. They can’t be separated.

After living with this book for a while, I was left with the sense that the natural state of human beings is not health but illness. As Ella’s Father says, “Pain is the awareness of being alive.” What I think Nervous System does so well is illustrate how both our life stories and the stories of our relationships can be stories of illness. Like Ella, both your parents are doctors. Do you think that instilled in you an exceptional interest in and/or awareness of that confluence of illness and affection?

LM: Absolutely. Not that this is an autobiographical novel—only that my particular experience of growing up with illness and parents who cared for me as doctors illuminated how there are two ideal states: health and love. But both narratives are often troubled by the fact that reality is not order but chaos, and there’s no manual for dealing with chaos. We deal with it (in our bodies and relationships) in an imperfect manner. In many ways, this is a novel that speaks about the failure to achieve so many ideal states, though not necessarily in a negative manner. Being imperfect describes what being human is.

MM: I love that idea of two ideal states of health and love. I’m going to keep thinking about that.

Like her parents, Ella is a scientist, but, unlike them, she studies the stars. Why did you decide to make her an astrophysicist, and especially a failing one?

LM: I always thought of Ella as a poet. She has a speculative way of thinking about the cosmos which translates into associative language. While I was figuring out who she was, I was reminded of two scientists I interviewed when I still worked as a cultural journalist. One was an astrophysicist, the other a mathematician, and they were both poets. That seemed strange, and we talked about this. I don’t remember the actual conversation, but I did come to understand that abstract thinkers have a capacity for putting things they do not see into language, into images. Things whose existence they can only prove through equations—for example, until very recently, black holes were only the product of mathematical proof. That’s when I realized it made perfect sense for Ella to be interested in that discipline. The problem for Ella is that she arrives a little late to astrophysics. She is disappointed by a technology that allows us to see the previously unseeable. There is nothing left for her to imagine.

MM: There’s a paragraph that comes in the first few pages of Nervous System that really stands out to me in our current context.

It was while thinking about blackouts and bottomless holes that the desire to get sick ignited in her. Ella considered it but couldn’t decide on an illness. A cold or a flu wouldn’t give her the time she needed to finish the thesis. Pneumonia would keep her from working. Cancer was too risky. Then her memory turned to her Father’s bleeding ulcer, which had kept him bedridden for several months: she imagined herself lying in a different bed, computer on her lap, eating poached eggs and insipid crackers and taking irritating sips of on the sly.

It feels both eerily prescient and a little transgressive after the past year we’ve had. To wish to retire from the world with an illness! I know you’ve thought about illness and literature for a long time, not just in the context of the pandemic. Can you talk a little about what you were thinking as you were first writing that section, and how you feel reading that paragraph now? Have your feelings changed?

LM: Two things came to mind. The first was Virginia Woolf’s 1925 essay “On Illness,” in which she wonders why being ill is not considered a literary theme like war, love, even jealousy. She describes how prevalent illness is in everybody’s lives, how it could create such interesting metaphors. She goes on—and this is the second thing I was thinking about—to speak of the privilege of being in bed, off-duty, how this time away from the productive life allows for the surge of poetry. This contradicts our idea, and experience, of suffering in bed because we are subtracted from regular life, but Woolf sees in it an opening for imagination and, I think, for writing. I have to add here that at the time I was feeling a little desperate myself with the way in which my teaching—so many courses, so many students, and especially so much grading without any assistance—interfered with my writing and sometimes brought it to a halt. If only I were sick and had to take a semester off, I thought. That idea later seeped into the novel, although by then I’d gotten a grant to spend a year writing in Berlin and wanted to be in my best shape to write.

MM: So much better to get a grant than to get sick! You and I spent many hours over Skype reviewing my questions, for which I’m eternally grateful. The language of this book is both painstaking and playful, and it wasn’t an easy translation. I’m always curious about what the experience of being translated is like for a writer, but especially in this case. Did the number of questions I had inspire confidence, fear, or a mixture of both)? What is it like to read yourself in translation?

LM: Ah, Megan, you know I’d rather avoid reading myself in translation, even if it’s your translation and I am sure I won’t suffer—much to the contrary! I also make sure not to reread my own books after they are published (unless I’m asked to read an excerpt out loud) because there’s always something I’d like to change, something that doesn’t feel quite right. That’s why I’ve decided that I’ll only answer questions from translators. In the case of English, which is a language I am fluent in, if something in the question doesn’t make sense I’ll go back a couple of pages to see if there was any misconception, because I am aware that the way I work with language is very precise but at the same time associative, and this associative way of working with language can make certain moments a little obscure. So I don’t mind questions at all, and yours were not so many. (And you know? I mistrust translators who don’t ask questions!) I have learnt tons of English nuances while answering them and discussing options with you. And, for this particular novel, creating an equivalence of the words in italics was so much fun!

MM: It was! That kind of collaborative work is one of the most enjoyable things about my job. And I was just going to bring up those italicized word sets, which you’ve called “excluded terms.” They’re sort of a poetic or stream-of-consciousness commentary—I think of them as synapses firing in the character’s head. Were they always part of the novel? Did they arise organically or were they a conscious decision? How do you think about those series?

LM: Yes, in those series there are words that match and then maybe one that is a “término excluido,” that doesn’t match exactly but that perhaps rhymes or relates in some other way. I agree with you: these words reflect moments when Ella short-circuits, stresses out, loses it and lets flow what comes convulsively to her mind. And because they reflect moments of agitation, I chose to use no commas to separate them. This appeared immediately, while writing the first pages of my draft, in the same way chopped sentences appeared as I started writing Seeing Red. While that stylistic strangeness appeared without my intervention, so to speak, the conscious decision was to leave it there and make it work throughout the novel.

MM: And my final question: What’s next for Lina Meruane? I know you’re leaving for Mexico soon—what will you be working on? What are you thinking about these days?

LM: I recently published a book—Zona ciega —on blindness. It consists of three essayistic pieces that use reflections and literary materials that I’ve compiled over the years on this subject. As you know, the Chilean uprising of October 2019 gave way to the police force shooting directly at people’s eyes, looking to blind them. It was horrifying. Hundreds of eyes were lost, and two people were completely blinded. It was also in line with what Jasbir Puar calls the “will to maim” by our democracies, only that maiming in Chile and elsewhere was done to the civilian eye. I thought that blinding was not only literal but also symbolic, because vision is historically equated to power. (Oedipus and Tiresias are early incarnations of this idea.) I also realized that blind women have been neglected. So I wrote about all of these things in Zona ciega. But writing essays means tons of reading and consulting an enormous bibliography. It’s exhausting. So I’ve decided to work on something that does not require that kind of work, something creative and shorter than a novel, something I’ve never tried before: a play. That’s what I’ll be doing, or trying to do, at the “One Hundred Years of Solitude Residency” in Mexico where Gabriel García Márquez wrote his great novel in the 1960s.

Megan McDowell has translated many of the most important contemporary writers from Latin America, including Alejandro Zambra, Samanta Schweblin, Lina Meruane, and Mariana Enriquez. She is the recipient of a 2020 Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and has been short- or long-listed for the International Booker prize four times. Her translations have appeared in publications including The New Yorker, The Paris Review, the Atlantic, and Harper’s. She lives in Santiago, Chile.

More Interviews