Show Me Your Shelves | David Heska Wanbli Weiden

Interviews

Show Me Your Shelves is a regular book column by Gabino Iglesias. In this edition he talks with David Heska Wanbli Weiden, author of Spotted Tail and Winter Counts.

Denver is one of my favorite cities. Last year I had the chance to visit twice. During my first visit, I did a couple of readings. One of them was Noir at the Bar, put together by writer Sam W. Anderson. That night, I had the chance to meet David Heska Wanbli Weiden in person. He was a mellow guy with a lot to say about publishing, so we hit it off. He was excited about the release of his novel later in the year. That novel, Winter Counts, eventually landed in my mailbox in ARC form. I devoured it and loved it. It is a timely, heartfelt narrative about the opioid crisis, but also a story about Native American identity and heritage that focuses on the Sicangu Lakota of the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota. Weiden writes with his heart on his sleeve, but also with a wealth of knowledge about the many ways in which the law in this country has failed Native Americans and turned reservations into places where justice is what you make of it. I wanted to know more about what’s on Weiden’s shelves, and here we are. This is what he had to say.

Gabino Iglesias: Who are you and what role do books play in your life?

David Heska Wanbli Weiden: I’m a book-obsessed Native person! I’m an enrolled citizen of the Sicangu Lakota nation, now living in Denver, Colorado. My earliest memories are of reading comic strips, cereal boxes, anything. Although my parents struggled financially, they were voracious readers and supported my library habit and bought as many books for me as they could afford. I realize now what a sacrifice they made, forgoing their own purchases so that I could have the latest Scholastic children’s paperback.

Now, I’m honored to be a member of several different literary communities. I’m so grateful to the crime fiction world for embracing Winter Counts and giving it such wonderful praise. The Native American literary community has been truly supportive as well, and I’ve tried to give back by mentoring several emerging indigenous writers and helping to get them published. I’ve also made many friends in the children’s book world, and I’m thankful to them for their support of my nonfiction book for middle-graders, Spotted Tail.

When I’m not writing books, I’m teaching them. I’m a professor of Native American studies and political science at Metropolitan State University of Denver, and I also teach in the MFA programs at Vermont College of Fine Arts and Western Colorado University and at the Lighthouse Writers Workshop in Denver. Finally, I’m the fiction editor for Anomaly journal, and also write occasional literary essays and book reviews for various publications.

As you can imagine, all of this doesn’t leave much free time, especially as I’m raising two teenage boys and driving them to what seems like hundreds of events and activities. I’m forced to use my time very efficiently, and I’m often sketching out story ideas in my head while driving. Two years ago, I wrote an entire chapter of Winter Counts while parked in my car at my son’s flag football practice. My reading time usually occurs late at night when my kids are asleep, and I really treasure those moments when I can dive into a great novel.

GI: Winter Counts is unapologetic about showing the treatment of Native Americans throughout history. Were you ever worried about how that truth was going to be received or how it could affect your chances of getting it published?

DHWW: Yes, I was very worried that no publishers would be interested in a literary thriller set on a Native reservation. Not to mention, the novel is very critical of the US government’s policies toward Native Americans regarding criminal justice, health care, education, and food sovereignty, and I wasn’t sure how readers would react to those critiques. But I decided that I needed to tell the story as honestly as I could, whatever the consequences.

Happily, both the publishing world and readers reacted very positively to the novel, and nearly everyone who’s reviewed it has mentioned that they appreciated learning about these policies, which are not well known outside of the indigenous community. I think the lesson here is that authors shouldn’t try to write to the market, but should focus on telling their stories without filters.

My hope was that Winter Counts would help to increase understanding about some of the legal and political issues in the book, especially of the Major Crimes Act, the congressional law that prohibits Native nations from prosecuting serious felony crimes that occur on their own territory. Because of this unjust law, thousands of criminals are being released without any punishment back into their communities. I’m happy to report that I’ve received scores of messages from readers who have told me that they’ve been enlightened about these issues, and they often ask how they can help. Fixing the criminal justice system on reservations will not be easy, but the first step is raising awareness of the problems.

GI: While identity and history are at the core of Winter Counts, the narrative also plays with the violence and pacing of classic pulp novels and deals with topics that make it fit nicely into contemporary crime fiction. Why did you think crime was the way to go with this story?

DHWW: To be honest, I didn’t consciously set out to write a crime novel. I’d previously written a short story featuring the novel’s protagonist, Virgil Wounded Horse, and thought that I’d said everything I had to say about him. But over time, I realized that I hadn’t fully explored his world, so I decided to return to the character and write a novel about him. Because Virgil is a hired vigilante on the Rosebud Reservation who beats up child molesters and other criminals for money, it fit into the crime genre pretty naturally. Not to mention, mystery, thriller, and suspense novels are my favorite, so it was a natural process that led me to writing a Native American crime novel. I lucked out in terms of timing, because there’s been a recent renaissance of crime writers of color creating incredible new works of mystery and suspense fiction. Many of my friends in the genre—S. A. Cosby, Marcie Rendon, Tori Eldridge—are writing some of the most exciting books out there, in any genre.

GI: Your work is a superb addition to a growing movement that is currently showing the power of Native American literature. You’re joining people like Stephen Graham Jones and Erika T. Wurth in telling not only the story of your people but also tackling lingering tropes about Native Americans. Why do you think we’re seeing this overdue explosion of Native literature?

DHWW: Well, you’re very kind to include me with those authors and in the new movement of Native writers. And please don’t forget some of the others: Brandon Hobson, Kelli Jo Ford, Tommy Orange, and a whole bunch of emerging indigenous writers you’ll be hearing from soon.

As to why this is happening now, I think there’s been a real change in the publishing industry that reflects a willingness to include previously marginalized voices. I think there’s also a realization that writers of color can write not only traditional literary fiction, but spec fic, fantasy, horror, crime—you name it. There’s also been a host of new organizations that support diverse writers: Kweli, Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation, and others. And of course, many of us—including you, Gabino!—are quietly working to help these emerging writers. It’s a great time for literature, even though it’s a tumultuous time politically.

GI: Can you give us five books you think will help people understand the Sicangu Lakota?

DHWW: There haven’t been many published books by Sicangu writers, sad to say. Luckily, we have the prolific and talented Joseph Marshall III, who’s written nonfiction, fiction, and children’s literature. My favorites of his are The Lakota Way: Stories and Lessons for Living and The Journey of Crazy Horse: A Lakota History. But all of his books are wonderful. Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve has published a number of books for children, including Grandpa Was a Cowboy and an Indian and Other Stories. I also highly recommend Life’s Journey―Zuya: Oral Teachings from Rosebud by Albert White Hat, Sr.

Finally, I feel somewhat embarrassed to mention my own children’s book, but I published Spotted Tail with Reycraft Books in 2019. It’s the first biography for children of the great leader of our nation, Chief Spotted Tail, and it won the Spur Award from the Western Writers of America in 2020. I wrote it so that Sicangu children could read a picture book about one of their own. The book has amazing illustrations by Jim Yellowhawk and Pat Kinsella; their art is truly great. I sent free copies to every elementary school on the Lakota reservations and had been planning to visit those schools, but the pandemic ended that. But I’ve heard from many teachers and parents on the reservation who love the book and who have thanked me for writing it.

GI: The house is on fire. Your loved ones and prized possessions are safe. You can grab a handful of books from your shelves before running out. What are you grabbing?

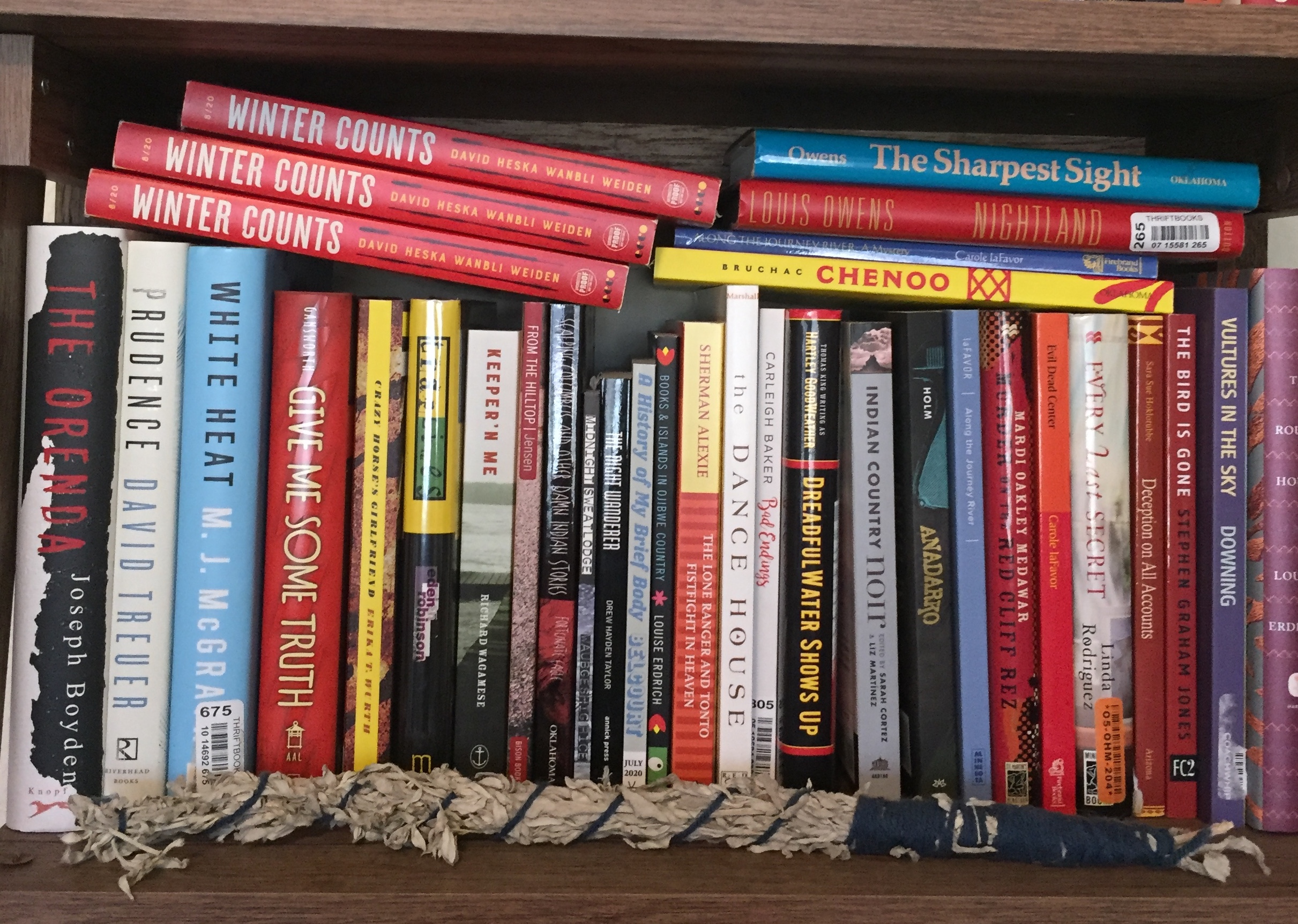

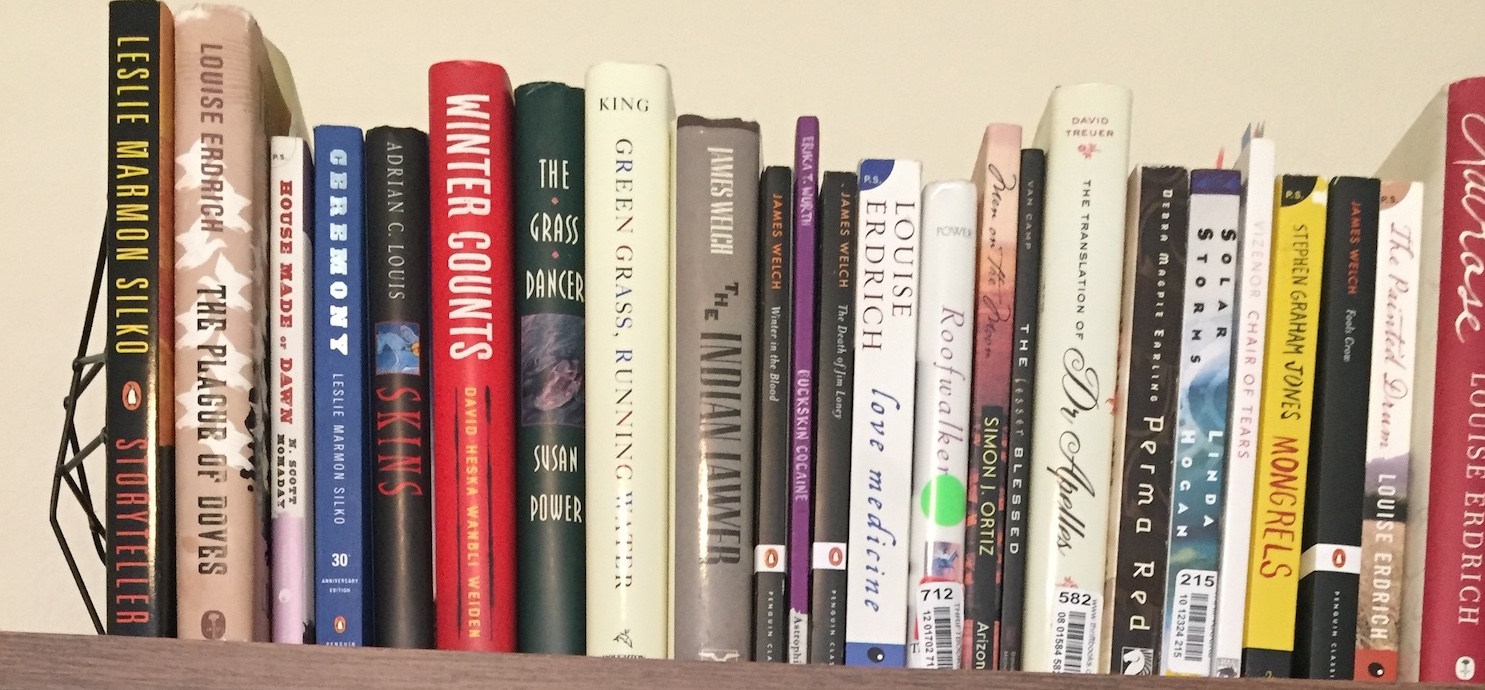

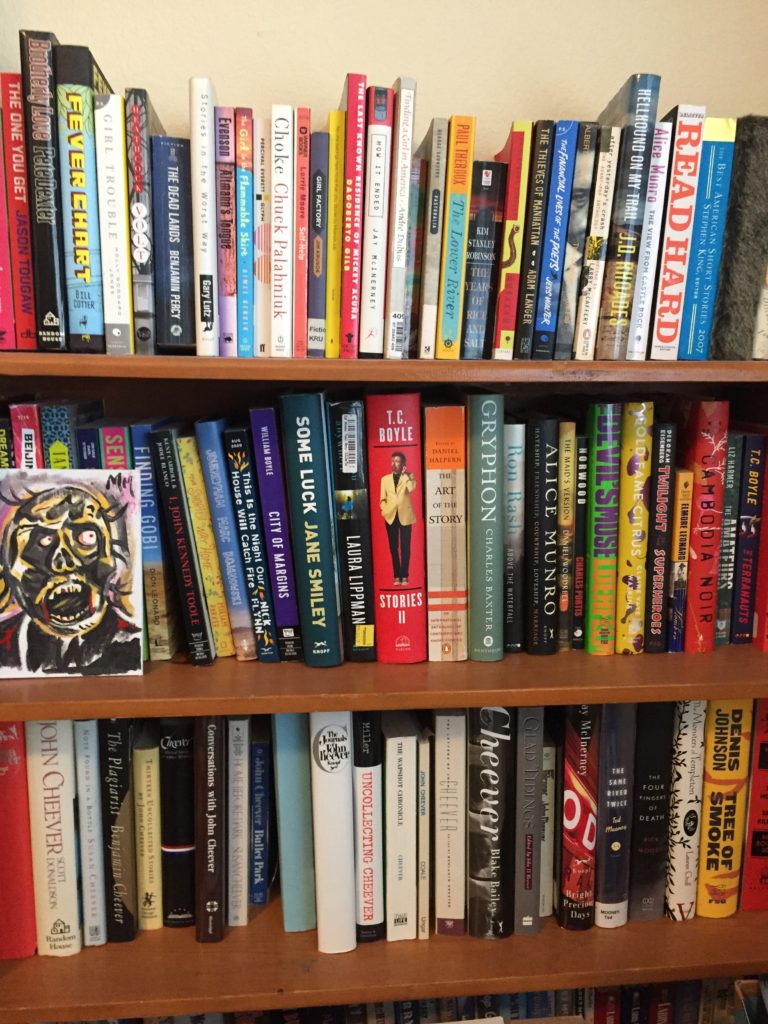

DHWW: Without a doubt my first edition of Winter in the Blood by James Welch. That purchase was one of my few indulgences after receiving my book deal with HarperCollins. I’d also grab my copy of The Uncollected Stories of John Cheever 1930–1981, because it’s so rare. It’s an advance review copy, not a bound book, and only a few hundred copies of it exist. The publishing company, Academy Chicago, had a contract with the estate of John Cheever to publish his short stories that hadn’t been previously included in any collections, but Cheever’s family objected to the contract signed by Cheever’s wife and sued to terminate the agreement. Ultimately, the book was never published, which is why the ARC is so valuable. I’m a longtime fan of Cheever’s work and obtained it by accident. It’s in mint condition, so I’ve never read the stories, as I’m worried about damaging it!

GI: Can you recommend more crime fiction and some nonfiction that explore identity and look at the United States with a critical eye and that you consider must-reads?

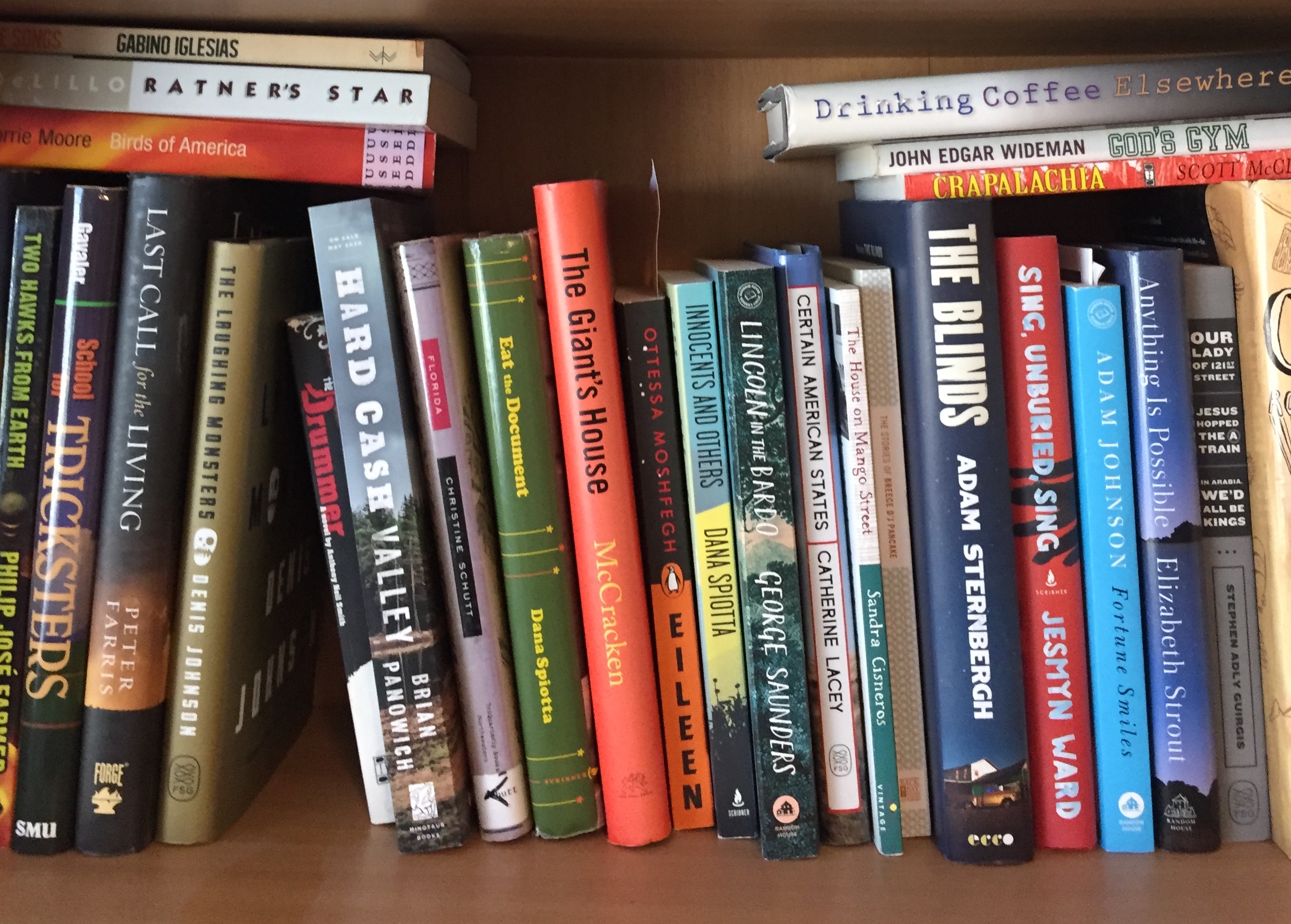

DHWW: We’re lucky to have some truly wonderful books that are not only page-turners but also thoughtful examinations of societal issues. The Round House by Louise Erdrich, which won the National Book Award in 2012, examines issues in tribal justice systems as well as being an amazing character study. Bluebird, Bluebird by Attica Locke is one of the best crime novels I’ve ever read as well as being a powerful reflection on race and justice. Most recently, Your House Will Pay by Steph Cha deals with the 1992 race riots in Los Angeles and how they affected two families. It’s a riveting read that stays with you long after you finish it.

For nonfiction, I strongly recommend The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee by David Treuer. This book—nominated for the National Book Award—is an amazing blend of history, memoir, and reportage. Treuer covers the last two hundred years of Native history with wit and shrewd observations about American policy toward its indigenous peoples. It truly should be the first book to read for anyone looking for a broad overview of Native history in America. Treuer’s earlier work of nonfiction, Rez Life, contains more of his personal history but is just as compelling. For those who want a more scholarly overview of how American law has affected Natives, Walter R. Echo-Hawk’s In the Courts of the Conqueror: The 10 Worst Indian Law Cases Ever Decided contains detailed analyses of the legal doctrines used to subjugate the original people of this country. For just one example, the Supreme Court in Johnson v. M’Intosh (1823) ruled that Native Americans possess no original title to the land of this continent, because their ownership interests were extinguished when the first European settlers came to North America. Yes, that’s right: The U.S. Supreme Court held that American Indians have only a right of occupancy, not of ownership, because of a legal theory derived from the Catholic Church called the “Doctrine of Discovery.” That doctrine holds that Christians have superior claim to lands over non-Christians, even if the non-Christians have lived there for millennia. That case set the stage for the removal of Natives from our homelands and our relocation to reservations, which were really prison camps when they were first created.

GI: As a fellow writer who jumps between languages, I loved learning a few Lakota words and sayings. Why did you decide to include those?

DHWW: I really struggled with the decision to include some Lakota words and phrases! Not just including those words, but whether or not to provide some explanatory material in the text. In the end, I took a middle ground: I sometimes provided a few words of context and sometimes relied on the reader to do the work of looking up the meaning of a phrase. A few readers have suggested that a glossary might have been useful, but that idea never even occurred to me. Overall, I’m happy with the balance that I struck in the novel. I should note that I’m not fluent in Lakota by any means, so I relied upon the generous assistance of some folks at the tribal college on my reservation, Sinte Gleska University. They saved me from making some embarrassing mistakes.

GI: Publishing a novel during a pandemic is no easy task. How have you adapted? What have you been doing to get the word out and how can we help?

DHWW: Yes, it was difficult to pivot to the changed landscape of publishing when the pandemic hit, especially given that no one had an inkling of what was coming. Every single one of my scheduled events was canceled, including some vitally important trade fairs like BookExpo, where authors get to meet librarians and booksellers. I had no other choice than to set up as many virtual events as I could, and I wrote a number of essays related to the book, including articles in the New York Times, CrimeReads, and The Strand magazine. I also decided that I would be especially attentive to my readers, and I’ve responded to every single person who’s sent me a message or note.

As to how folks can help, I’d suggest that readers continue to buy books, preferably from independent bookstores, and spread the news if there’s a novel that you love. Word of mouth is the best way to support your favorite writers.

GI: Little David is ten or twelve. What is he reading/consuming? Can you tell us about some books that shaped you as a writer or made you want to write?

DHWW: What a fun question! My dad had a stash of spy novels, and I devoured Ian Fleming’s James Bond books. Around that time, I discovered classic science fiction—I loved Isaac Asimov’s Foundation novels, Ray Bradbury, Robert Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke, and others. My parents had a subscription to the Book of the Month Club, so I’d read the main selection, whatever it was. I recall that there was a copy in our house of Vine Deloria’s Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto, which I tried to read, but it was way over my head at the time. I think every Native family had a copy of that book back then, as I recall seeing it at my cousins’ houses.

In my teen years, I was obsessed with Stephen King and read everything he published. I also started reading literary fiction then: John Updike, Hemingway, Faulkner, John Cheever. The lightning bolt came when I stumbled upon a copy at the library of James Welch’s Winter in the Blood. I believe that was the first Native-authored novel I ever read. It seems really stupid now, but I just didn’t comprehend that Native people could write books about our own people. The book was disturbing, and I didn’t like it at first. But it started a fire inside me—a realization that I could write fiction about our people and our experiences. I hope I’ve done justice to James Welch and other indigenous writers with Winter Counts.

Gabino Iglesias is a writer, professor, and book reviewer living in Austin, Texas. He is the author of Zero Saints and Coyote Songs and the editor of Both Sides: Stories from the Border. You can find him on Twitter @Gabino_Iglesias.

More Interviews