The Best Atmospheres: A Conversation with Guadalupe Nettel

Interviews

By Erik Noonan

To me, the Nettelian moment par excellence comes in a paragraph toward the end of The Body Where I Was Born. The anonymous protagonist leaves her public high school in a banlieue in the south of France, where she was staying with her mother, goes back to Mexico to live with her grandmother, and enrolls in a French academy where she sees her world anew. The racism of the school, with its majority white student body and dark-skinned administration and staff, strikes her as a strange departure from the norm in her home country; and her French and Maghreb classmates, the children of foreign diplomats, ignore her because of her vocabulary and pronunciation, while the bourgeois Mexican kids refer to her as a “hobo” because of her clothing and school supplies. Finally she notes the school’s resemblance to the prison where she visits her father, who has been falsely convicted of embezzlement. The passage distills many of the writer’s themes, and it has a thrilling and memorable effect.

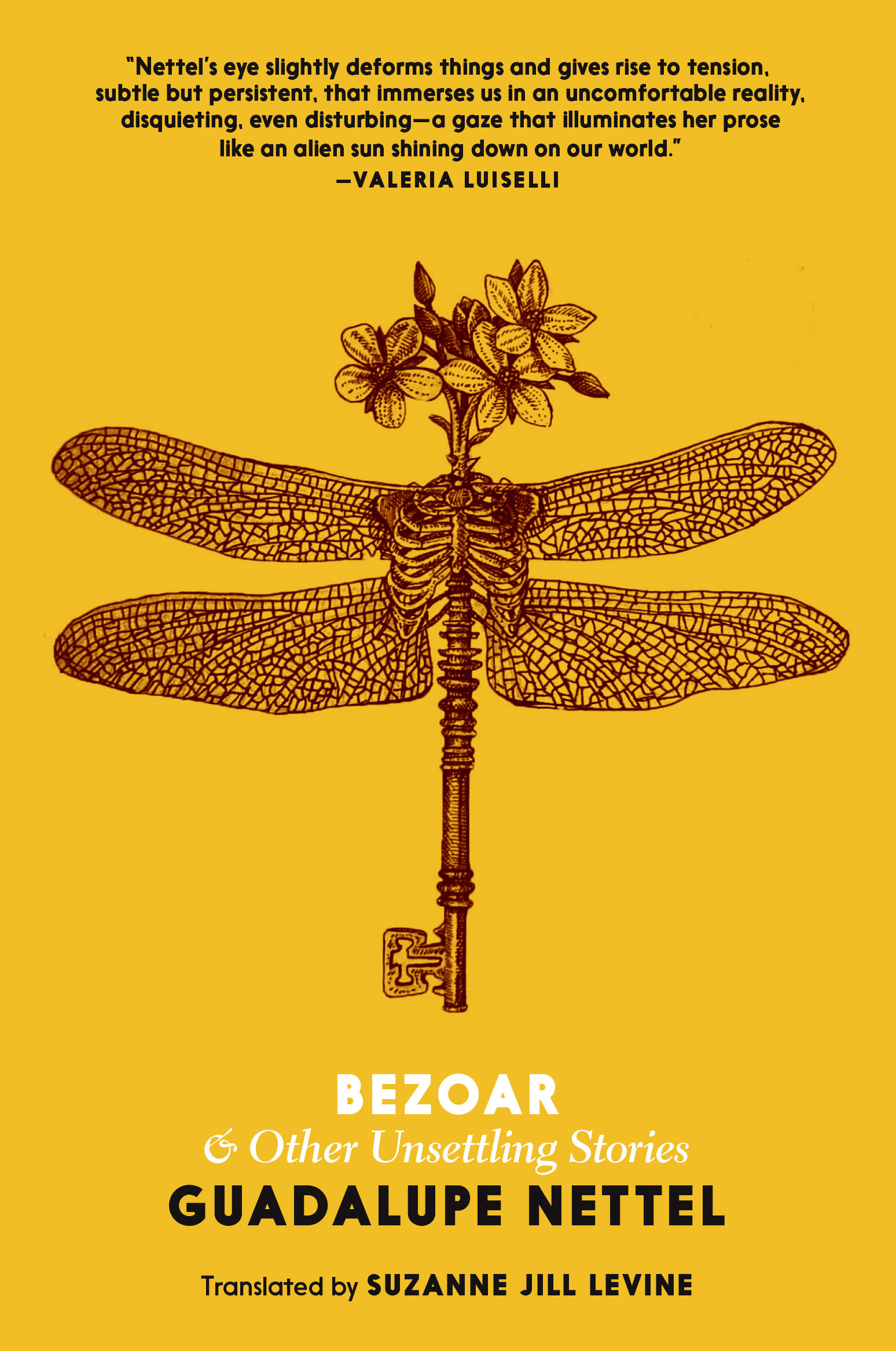

The occasion of the present interview is a short story collection entitled Bezoar and Other Unsettling Stories, published today by Seven Stories Press. The translator of the volume, Suzanne Jill Levine, put me in touch with the author, and we corresponded by email. Guadalupe’s responses haven’t dimmed the mystery and allure of her books for me, but intensified them.

Erik Noonan: In the Italian author Italo Svevo’s novel La coscienza di Zeno, the protagonist is trying to quit smoking, and so he is addressing his story to a psychiatrist, in an attempt to disentangle the habit from its causes; and in “Bezoar,” a story in your new collection, Bezoar and Other Unsettling Stories, the protagonist is keeping a journal while staying in a psychiatric inpatient clinic in the midst of a psychotic break. But Dr. Sazlavski, the psychoanalyst in El Cuerpo en que nací, has a wonderful frivolity, a fine excess—it’s as if the clinician doesn’t really need to be there, except as somebody for the narrator to talk to. Is the doctor just an expedient, a device, a convenience? Do you have a sense of why it felt necessary to have your character speaking to a shrink?

Erik Noonan: In the Italian author Italo Svevo’s novel La coscienza di Zeno, the protagonist is trying to quit smoking, and so he is addressing his story to a psychiatrist, in an attempt to disentangle the habit from its causes; and in “Bezoar,” a story in your new collection, Bezoar and Other Unsettling Stories, the protagonist is keeping a journal while staying in a psychiatric inpatient clinic in the midst of a psychotic break. But Dr. Sazlavski, the psychoanalyst in El Cuerpo en que nací, has a wonderful frivolity, a fine excess—it’s as if the clinician doesn’t really need to be there, except as somebody for the narrator to talk to. Is the doctor just an expedient, a device, a convenience? Do you have a sense of why it felt necessary to have your character speaking to a shrink?

Guadalupe Nettel: The Body Where I Was Born is a memoir or an autobiography in the form of a novel. Practically everything I say there happened, but some things are slightly modified. My father, as I say in the book, was a psychoanalyst. He took up that career a little later in life, after pursuing applied mathematics, and I watched him undergo analysis with the psychoanalyst for whom the character is named. Shortly after publishing the book, I ran into Dr. Sazlavski, the real one, in a cafeteria. She remembered me and told me that she had read the book and recognized some of the episodes. My father was interested in Jacques Lacan’s ideas. He argued, among other things, that the analyst was much less necessary for analysis than one might believe, and the less he spoke the better. In fact, he said half in jest that he could be replaced by a monkey and nothing would change. A shrink that doesn’t speak baffles me and makes me laugh a little, and I saw irony in Dr. Sazlavski’s silence. On the other hand, while I was writing, the psychoanalyst in the novel represented the reader who always tries to psychoanalyze the author. I was telling my story and sharing my most intimate memories, and as I did so, I imagined the reader trying to analyze me. The questions that the narrator asks the doctor, this other person who doesn’t respond, are questions that I was asking my imaginary interlocutor, the reader, who felt to me as if they were right there at the head of the couch. While I wrote this book, I was reading Portnoy’s Complaint by Philip Roth—in which Portnoy talks to his psychoanalyst, Dr. Spielvogel—and was fascinated by it. Dr. Sazlavski is also a secret homage to that novel that I like so much.

EN: A little boy in the Egyptian author Sonallah Ibrahim’s novel Stealth overhears the women in his family mention a department store bombing in passing while they’re talking about the dresses in fashion that season. I thought of this scene while reading the part in El cuerpo en que nací where the protagonist describes how the other children are familiar with their parents’ flights from violence. They pick it up around the dinner table, in Chilean or Argentine Spanish, and leave it behind while speaking Mexican Spanish outside their homes. You develop this theme in your novel Después del invierno when the Boston Marathon attack appears as an event in the life of an individual, the character of Claudio. Is this your version of Stendhal’s pistol shot at a concert, politics in prose? What place do political subjects have in a novel? How does the political become a theme in fiction?

GN: It happens naturally, without my intending it. There are events that are prominent in my conscience, and when I least expect it, they appear in what I write, as if someone were knocking on the door, demanding to be seen and heard. The dictatorships in South America during the nineteen seventies constituted one of those events, because I spent my childhood surrounded by exiled children, often orphaned by a parent (sometimes both), whose families had experienced traumatic events. The Boston Marathon also left a deep mark on my conscience, even though I was not there, and so did the terrorist attack on Charlie Hebdo in Paris. In Mexico, violent events have occurred and are occurring, such as the disappearing of the forty-three students from Ayotzinapa or the femicides that have marked us all and made us go out into the streets to demonstrate. This explains why Mexican literature of recent decades returns over and over to the subject of violence. Stendhal rightly said the novel is a mirror that one carries along a high road, and sometimes the road is full of blood and atrocities. I also believe that many other more everyday and apparently innocuous things, such as the characters one chooses (their origin, their history, their gender, their thoughts), even the language, the words we use, have a subtle political charge that—whether we realize it or not—is present in a text.

EN: In your interviews you’ve stated that you’re not really interested in national literatures per se, but I have to say that the presence of myriad cultures among the children at the Villa Olímpica housing project in El cuerpo en que nací also reminds me of Mexican literature itself, Mexican writing, not as a national entity, but as a kind of refuge for newcomers from across the literary galaxy. The Uruguayan poet Eduardo Milán, for example, lives in Mexico City, I believe. And Luis Cernuda immigrated to Mexico and felt at home there. Are you aware of distinct Mexican currents in contemporary literature?

GN: It’s true a lot of writers and artists in general have gone into exile in this country. Not only during the Spanish Civil War and the dictatorships of the ’seventies, but also during the Second World War. André Breton, for example, lived here a few years and was fascinated by Mexico. All those people have had a major influence. I read my contemporaries with great interest and stay abreast of what’s happening on the current literary scene. As the director of a journal, The University of Mexico Review, I’m required to do this and the truth is I really enjoy it.

EN: If El cuerpo en que nací is a portrait of the artist as a young woman, then Despues del invierno strikes me as an allegory of inspiration—where Cecilia, the Parisian artist from Oaxaca with two lovers (two muses) thinks of the people she has known and starts to “co-opt them as characters” at the end of the novel. Both books tell stories of how the contemporary artist comes to create her work. Do you see a progression from one book to the other, a change in your process or technique? And if so, how would you characterize it?

GN: The Body Where I Was Born is more of a linear book and it was written in a more impulsive and urgent way. My first son was one month old when a magazine asked me for a long autobiographical text, about twenty pages. I accepted the commission and began to reflect on the circumstances under which I had been born and compare them with the ones that befell him. Writing that text at that time was like a detonation that opened a mine of memories and I couldn’t stop writing. The text I’d originally intended to be an essay became an autobiographical novel or memoir. After the Winter, by contrast, was written a lot more slowly. I started it in Paris when I was still living there, and I interrupted it several times to write other things, among them The Body Where I Was Born and El matrimonio de los peces rojos (Natural Histories in English) and it was the book I returned to, whenever I finished what I was writing. The process lasted almost ten years. This allowed the perspectives of my characters to change as they matured over the long period when I was writing it. But you’re right to say there’s an evolution in technique. Even though After the Winter is a book with a high autobiographical content, the experience remains diluted by the fiction. I used newspapers from the time I was studying in Paris and also some letters I’d exchanged with people. So the writing method is totally different.

EN: Apart from the artist figures in your books, Claudio, a New York editor in Después del invierno, is your most fascinating character in some ways. He’s complex. For example, there’s a remarkable chapter that relates his first sexual experience. Claudio is growing up in Cuba, and a boy entices him over to his house, where he can peep at the cleaner, a woman whose complexion is dark. But the encounter happens with the friend, and Claudio reacts by feeling shame for having sex with a boy. Also, instead of examining his emotions about this, he decides that he should never again take an interest in such a person with dark skin. Years later he confesses his torment over this “absurd, innocent episode” to his girlfriend, and instead of sympathizing, she tells him he is a closeted gay man. And when he breaks it off with her, she hangs herself! His suffering is extreme. And yet by other measures he is successful and happy. What is it that’s so striking about Claudio?

GN: The Claudio character was quite a challenge for me. I wanted to write about a macho, misogynistic, arrogant Latin man, of which there are so many, and in a sense recreate an archetype, and also do it in the first person, really put myself in his shoes. But then I wondered what his story had been, what kinds of experiences had led him to be who he was. I was partly inspired by well-known people, and I created a kind of Frankenstein with pieces of life from different people. What happens with Susana, the love of his youth that you mention, was something he already sensed from the first encounter between them. Susana had a fragile mind and was destined for an early death. And that’s part of what was so attractive to him: the fact that she would dote on him and depend entirely on him.

EN: Certain books stand out as key texts in your oeuvre, which you allude to, over and over—Julio Cortázar’s story “Axolotl” and Franz Kafka’s novella Metamorphosis, to name two. Then there is another kind of text, which appears in your work when a character sees herself reflected in it: a powerful example of this sort of allusion is when the protagonist of El cuerpo en que nací meets the Mexican poet Octavio Paz in France and hears him read his poems, and enters a new phase of her own Mexicanness; or when she finds her mother’s copy of The Incredible and Sad Tale of the Innocent Eréndira and her Heartless Grandmother by the Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez, and sees her family predicament in the plot. For me, the Márquez reference introduces a metatextual pleasure to your work, because the translator of your new book Bezoar and Other Unsettling Stories, Suzanne Jill Levine, wrote a study of Cien años de soledad, entitled El Espejo Hablado; and to the extent that your readers are familiar with the Boom and the context of twentieth-century Latin American literature, it is largely due to her efforts as a scholar and translator of such authors as Guillermo Cabrera Infante, Adolfo Bioy Casares, SIlvina Ocampo, Jorge Luis Borges, Severo Sarduy, Manuel Puig, and Julián Rios. How do you imagine the presence of literary works translated from Spanish in Anglophone literature? What, for you, is the relationship between translated and untranslated literatures?

GN: The generation of authors you mention, known as the Latin American Boom, created a very powerful, effervescent literature, full of vitality, and the work that Suzanne Jill Levine did to make it known in the English language is very important. Especially since it was a time when both American and British readers were still very closed to foreign literature. The number of books that had been translated represented a tiny percentage compared to what was published. It’s strange, because some of the authors of literature in English—Malcolm Lowry, Hemingway, William Bourroughs, Jack Kerouac, among others—were in Latin America and they talk about it in their books. And yet it still took years before readers began to take an interest in Latin American literature. In this sense, Suzanne Jill Levine was a pioneer who opened the way into a truly closed wilderness. The texts that she translated aren’t at all easy. They’re written in different dialects of Spanish (Colombian, Cuban, etc.) and they display a brilliant stylistic workmanship. I think Jill was brave to forge ahead with the project the way she did, and I admire her a lot for that.

I believe that reading foreign literature is a fundamental practice. It allows us to learn about other cultures and expand our empathy. In an amazing speech delivered during the reception of the Príncipe de Asturias Prize, Amos Oz said: “Reading a novel from another country is like being invited to other people’s living room, to their children’s room, their office, and even to their bedroom. You are invited to enter into their most secret sadness, their joy and into their dreams.” I totally agree. Foreign literature has the power to allow us to connect beyond ideologies, and to enter into a zone of intimacy and into the everyday life of other people and other nations, and to share their stories, their daily life, their fears, their hopes, and their life experiences. Usually, I am more easily convinced if I read a novel by a Syrian or Lebanese author than by any news coverage about bombing in their countries. There is something unreal, cold, and statistical about news coverage with which you cannot connect emotionally. Oftentimes, novels are more believable than newspapers or newscasts. I find the same thing happening with Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, Emiliano Monge’s Tierras arrasadas, Antonio Ortuño’s La Fila India, Aura Xilonen’s Campeón Gabacho, or Valeria Luiselli’s Tell Me How It Ends. All of them deal with immigrants from Mexico and Central America trying to get into the United States, as well as their horrifying experiences. Even though they are fictional texts, they have the power of the instinctive and emotional conviction you only find in good literature as they allow us to understand, and reflect on, immigration—a phenomenon that’s sometimes painful but can also be positive and enlightening for both cultures.

EN: This reminds me of a story that the Puerto Rican author Eduardo Lalo tells. One of his novels, Uselessness, came out in an English translation—also by Jill, in fact—while Hurricane Maria was tearing the island apart. He couldn’t receive mail, so he saw the book for the first time while he was visiting Texas to attend the opening reception of one of his art exhibits. He says he didn’t realize the text was his, until he’d sat reading it for ten minutes! Have you ever read your work in other languages? What’s it like to be translated?

GN: It gives me a bit of a shock to read myself in another language that I speak and understand, but it also amazes me. Translation is a delicate process. If it’s done badly or neglected, it can be harmful. It’s not like a poorly translated movie, where you have the images and the performances and you can pick up the inconsistencies in a translation right away. In literature, the language is everything! So if the translation is into a language I understand, then I at least try to read it and collaborate with the translator as much as possible. Respond to her inquiries until she has no more questions, give suggestions, correct errors. But I also try to respect her style and her interpretation. Trust the translator, since after all she (or he) knows her native language better than I do. What I would like is for it to feel totally natural and not like a translated text, and this can only be done by a native speaker. Finally, being translated into another language and having readers from other countries read me is a huge piece of good fortune.

EN: “Pétalos,” the title story of your 2008 collection, Pétalos y otras historias incómodas—your latest to come out in English, as Bezoar and Other Unsettling Stories—is an allegory of aesthetic pleasure, the experience of beauty. The narrator, a self-declared olfactorist, sneaks into women’s bathrooms in Rome to sniff toilets. We join him in his pursuit of a woman known only as La Flor, and we find out how he evaluates the stains and smells in the stalls. You write:

The best atmospheres are like states of mind, they can be sensed but not interpreted, and though I would recognize the exact tone of the indirect lighting, the murmur of the voices outside, and the plants that were everywhere, even in the bathroom, all that remains for me of that environment is a faded nostalgia, like the glow of a beautiful, distant memory.

This rather Proustian passage strikes me, not only as a description of the character’s obsession, but also as a statement of your own aesthetics. When you are writing, or when you’re reading a book by someone else, how important is atmosphere to you, and why?

GN: Atmosphere is very important to me, yes. It doesn’t just depend on the descriptions of the scene or the dialogues of the characters, but also and above all on tone and style. A totally demented plot can turn out to be plausible in a text if we have the appropriate atmosphere. To sit and write, I need to feel the atmosphere of a story, get it really clear, as much as the tone.

EN: The erotic often takes place at several removes in your work. Characters approach each other as voyeurs—whether the barriers between them are psychotropic, as in the case of Claudio and his heavily medicated American girlfriend Ruth; or a sheetrock wall and a terminal illness, as in the case of Cecilia and Tom; or a pair of binoculars, as in the case of the anonymous threesome in the short story “Through Shades” in Bezoar. Obsession pervades the imagination. Fantasy plays an important role. There’s a lot of masturbation. Yet conflicts break out between the characters’ rich inward lives and their relationships with others. For example, a girl confronts the protagonist of El cuerpo en que nací, and she denies liking the boy they both have a crush on. What is the role of the erotic in your work?

GN: The same thing happens to me with eroticism as with politics. Its emergence is not always deliberate. Sometimes the writing takes us and drives us on with a movement, an impulse of its own, an uncontrollable trajectory down unsuspected routes, and I think at moments like these the writer should get swept away by it. This is how eroticism appears in my texts. A psychoanalyst would say it’s an expression of the unconscious, the Surrealists would call it inspiration, an external almost magical force that suddenly visits us. I particularly remember the moment in the story “Bezoar,” the scene in which the protagonist has an erotic encounter with Victor in the garden at the party, her skirt smeared with semen. I was surprised myself when I wrote this. With the story “Mushrooms” from Natural Histories, the same thing happened, but it lasted almost the whole story. And the strangest thing: when I reread it now, I’m still surprised to have written it. As for voyeurism and mediation: to me anyway, eroticism almost always contains some element of the perverse.

EN: Lately in the USA, we sometimes hear about a Global Novel—perhaps a twenty-first-century version of World Literature, that Goethean notion which held such sway over academic disciplines in the second half of the twentieth century. For you, is this concept a journalistic convenience? Does it accurately describe a kind of book that really exists? Is it a false universal? A market category? Is it bound up in imperialism and neocolonial conquest? Does it contain an ideal, as a book that’s open to all, that anyone can lose (or find) themselves in?

GN: I’m interested in stories where cultures intersect and sometimes collide with each other, but I must admit, the idea of a global novel scares me. I imagine it as those cities where you see Starbucks, Sephora, McDonald’s, Brioche Dorée on every corner and you feel like you could be anywhere in the world and nowhere at the same time, what they call the Global Village, which ends up being horribly impersonal. On the other hand, Gabriel García Márquez said that only the absolutely local is profoundly universal. I don’t fully believe in either of the two ideas. I think we should find a “middle way,” and most of all I think a writer shouldn’t think about this kind of thing when she sits down to work, only about what she urgently needs to say.

EN: What are you reading these days?

GN: I recently read Vivian Gornick’s Fierce Attachments and Nuestra parte de noche by Mariana Enríquez, the novel that won the Herralde Award last year. I’m also teaching a university class on literature and disease this semester, so for that, I’ve been reading the Italian poet Alda Merini, Illness and its Metaphors by Susan Sontag, and The Plague by Albert Camus.

Erik Noonan is a writer from Los Angeles. For more, please visit eriknoonan.net.

A Bogotá 39 author and Granta “Best Untranslated Writer,” Guadalupe Nettel has received numerous prestigious awards, including the Gilberto Owen National Literature Prize, the Antonin Artaud Prize, the Ribera del Duero Short Fiction Award, and the 2014 Herralde Novel Prize. In 2015 Seven Stories published her first novel, The Body Where I Was Born. In 2018, her second novel, After the Winter, was published by Coffee House Press. Nettel lives and works in Mexico City.

More Interviews