I was a comic book fan in the 1970s, when superheroes flew and flashed and skulked and swung across dark city rooftops. Those plots were simple: a bad guy appears, does something bad, and a hero appears and fights him. That was it.

As an older fan, I see now that the true artistry of that Bronze Age (and earlier ages) was (a) the creation/origin of the characters and (b) the art. Your Jack Kirbys, your John Buscemas, your Joe Kuberts, all pioneers. The writers, the Stan Lees, the Roy Thomases, those guys were doing several titles per month. No wonder the stories were elementary. At age thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, all I wanted was to see muscle-bound dudes kicking the asses of muscle-bound bad guys anyway. Who wanted a complicated story? I used to count the panels of each comic book I bought to see how many fight scenes there were.

The good news is that, in the 1980s, the writing caught up. Read Watchmen. Read The Dark Knight. Those same heroes (or versions of them) are now subverted, viewed other ways. It’s not a surprise to me that Time magazine called Watchmen one of the Best Novels of the Last Century.

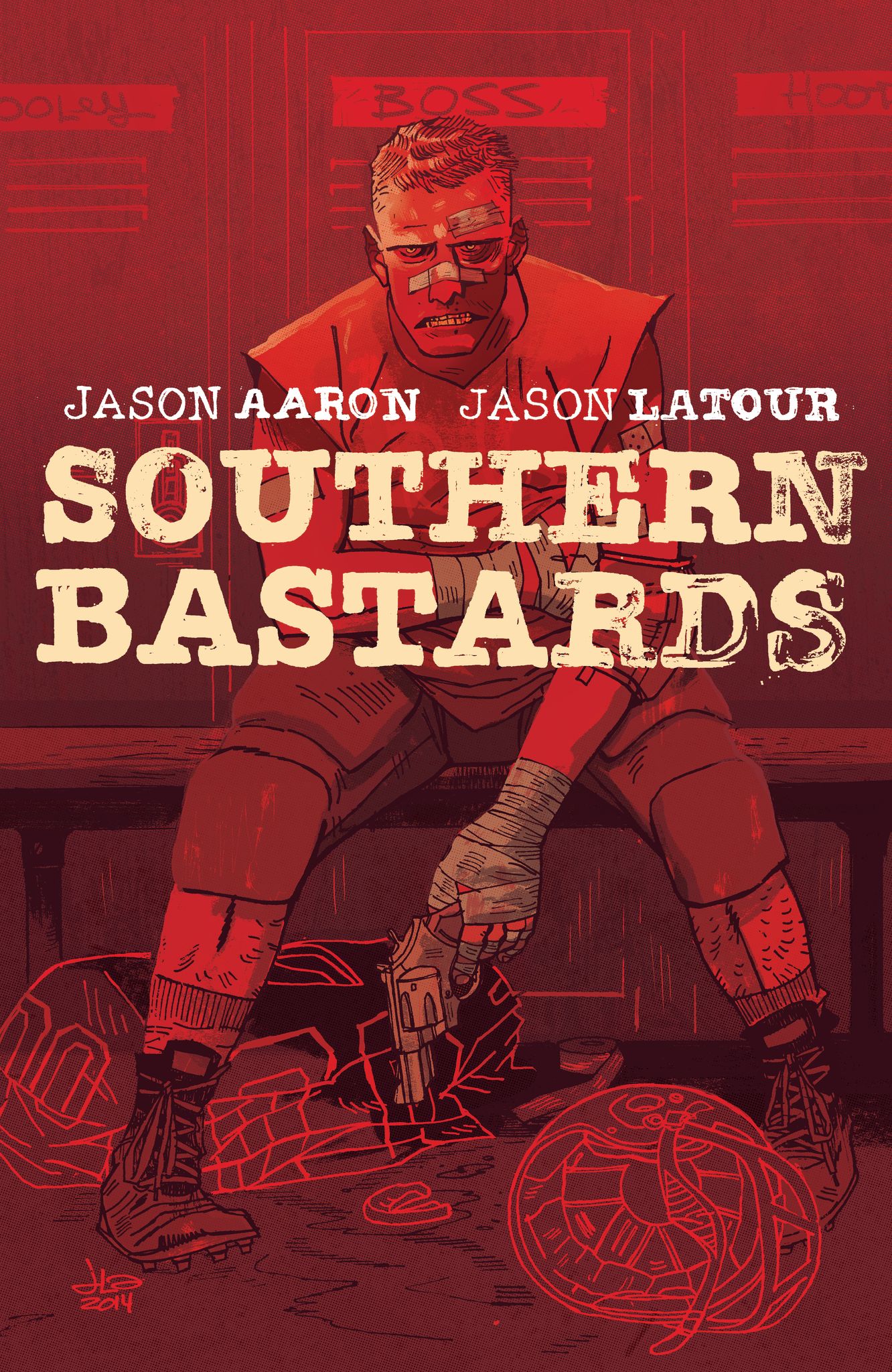

Which brings us to Southern Bastards. This was unlike any title I’d ever read. As an Alabamian who now lives in Mississippi, I saw and see the terrain of Southern Bastards on a regular basis. The violence, the landscape, the religion, the ignorance, the poverty, and, above all, the FOOTBALL. I won’t say too much about this series, except to say that it captures its subject matter and setting perfectly. Its writer and illustrator are both Southerners and are both keen observers. As someone who’s lived here most of his life, I flinch at Southern Bastards because it’s accurate and because it’s deeply critical. I keep reading it because the story is terrific and keeps changing. The man we think will be the hero in the first issues finds a fate I never saw coming. He’s an Alabama Buford Pusser, not atypical for this kind of story. And yet, just when we think we see the trajectory that Southern Bastards will take, the AstroTurf is yanked from beneath our feet and we see it’s a whole other ride altogether.

But that’s enough from me. Let’s hear from our two Southern creators, Jason Aaron and Jason Latour.

Tom Franklin: Two Southerners in comics. How did you meet?

Jason Aaron: We met through comic book circles, mutual friends, hanging out at bars, that sort of stuff.

Jason Latour: It’s a small community. Not a lot of Southerners were around at the time. I think I had a fake account on the Image [the comic book publisher] message board to mess with my friends.

JA: You say that like maybe you did, maybe you didn’t. [Laughs] You’re trying to disavow it now.

JL: No, what I meant was I don’t know if that’s how we met. If I remember correctly, I had a fake account with a picture making fun of Bear Bryant. I think I had to explain to Jason it was a joke.

TF: He was Alabama royalty. Bigger than Elvis, for me. I remember where I was standing when I heard Bear Bryant died.

JA: So do I.

TF: Southern Bastards has so many great Southern references. There’s Sheriff Buford Pusser from Tennessee. Hollywood made a couple movies about him. Did Walking Tall influence Southern Bastards? Or Buford Pusser himself?

JA: For sure. You can’t do a story about a Southerner with a big stick trying to clean up a troubled county without calling to mind Buford Pusser. We were very conscious of that, so we used his story to set people up to expect one thing and then, four issues in, pull the rug out from under them. The clue is right there in the title. The title isn’t Old Man Cleans Up County With a Big Stick; it’s Southern Bastards. It’s about a place where the bastards have won. And we see them win in a big way when [SPOILER ALERT!] Earl gets his head caved in with his own stick.

TF: That was worse than Ned Stark’s head getting chopped off in Game of Thrones—for me, at least.

JA: [Laughs] I think it was for Jason, too.

TF: I didn’t see Earl’s death coming. It’s set up so beautifully all the way through with the phone calls to his daughter. Who’s he calling, who’s he calling, who’s he calling— then we meet Roberta and she becomes the hero, I suppose. Although, I would even argue that Boss is our, what, antihero, protagonist . . . ?

JL: He’s certainly the focus. He’s not the hero, but he’s definitely the focus.

JA: He’s his own hero.

JL: A hero in his own mind.

TF: There are other influences, like the character McKlusky. He’s Burt Reynolds, right? Gator McKlusky? Your McKlusky, he looks a lot like Burt.

JL: The idea for the character came first, and then we decided to cast him as someone who looks like Burt Reynolds. I remember being really excited about the character and then sort of stumbling on the idea of drawing a guy like Burt Reynolds.

TF: Some Faulkner in there, too.

JA: References to Faulkner, the Compson family, they were a big part of what was Faulkner’s county? Yoknapataka . . .

TF: Yoknapatawpha. You can’t live here in Oxford unless you can say that.

JA: I took a Twain and Faulkner class in college, when I was at UAB, and it gave me a new appreciation for those authors. I’d read Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn, but nothing beyond that. I loved Twain’s travel writings especially. I hadn’t read much Faulkner at all, and those books stuck with me. So when we started talking about doing our own fictional county in the South, Faulkner certainly came to mind. The Burt Reynolds stuff—and not just Walking Tall but the whole Southern redneck crime genre from the 1970s—all that was a huge influence on me. I love those Gator McKlusky movies. What a great era for redneck crime.

JL: A sentence that’s never been said before.

JA: [Laughs] Can’t say that about every age.

JL: The golden age of redneck crime cinema.

JA: We’re also big fans of the Drive-By Truckers, and they did multiple songs about Buford Pusser. If you mix all that together with some of the real-life Dixie Mafia stuff, you sort of get the DNA of Southern Bastards.

JL: All the things Jason said, especially about the Drive-By Truckers. That’s a direct link. Their album The Dirty South is about how criminals look at a guy like Buford Pusser. When we first thought about doing a book together, we talked about a Southern crime story. Jason had the idea for a crime boss who also happens to be a high school football coach. Should I tell the tree story?

JA: You always tell the tree story.

JL: So I was obsessed with the nature of cyclical violence, of the things we bury underground that always grow back. At the time, I had a neighbor who let his dog run wild in the neighborhood. I’d go out of town and come back to find the dog had shit in my yard. One time, after I’d been gone a couple weeks, I came home, and there was a tree—what looked like a giant stick growing out of a turd—in my yard. As a joke, I said to my friends, “I should water this tree until it grows into something I can snap a branch off, then take revenge like Buford Pusser.” I told Jason that story, and it was like a switch flipped. All the ingredients started cooking together. So even though we were influenced by all these other stories, like most good stories, ours came together organically.

TF: The first issue of Southern Bastards opens with a picture of a dog taking a shit. That page says so much about the South.

JL: Which was in part an homage to the dog that inspired the story, but also a warning that there’s no turning back now, that this might be the mildest thing you see in the story. And the responses have been so funny to me. My mother lives close by and I watch her dog sometimes. It’s a perfectly normal thing to see a dog take a shit, but people’s reaction to seeing it drawn as a cartoon—you’d think it was something scandalous.

TF: If you would talk about how the two of you collaborate. I’ve collaborated on writing projects but never with a visual or graphic artist before. What’s the process? How does this amazing book get in my hands?

JA: Everything we do in comics is a collaboration. I can’t draw at all, so I’m never going to tell someone exactly how to draw what I’m writing. Jason and I figure it out together. When I’m writing for Marvel, it’s different. I’m working with people who I’ve probably never met in person, may never meet in person, people who live all over the world, so it’s a different kind of collaboration.

Southern Bastards began with me wanting to do a book at Image for the first time. I’d never worked at Image. I was friends with someone who had just started working there, and I started talking to him about a book. But it wasn’t me saying “Well, I have this idea for a book that I really want to do—let’s find somebody to draw it.” I asked myself who I’d like to work with. Jason and I had worked together on some Marvel stuff, and we’d become friends. Getting to work with somebody who I was already close to, and friends with, that was the important part. The relationship was first. The idea for the story came second.

JL: I’d agree with that. Creating a comic takes time, especially the time I take with this one, because I draw and color and help with the story. It’s important that we communicate with one another and share a common passion. This is one of the most unique things I’ve worked on, in terms of that process. I was thinking the other day that I’ve sat with Coach Boss as a character now for five years. That’s more time with Coach Boss than with members of my own family. [Laughs]

JA: Again, it goes back to what I was saying about the relationship being the thing you start with. This was always a book that we came up with together. I came in with a piece of it and you had other pieces. As I said, it wasn’t like I had this idea whole cloth called Southern Bastards and I just needed somebody to draw it. I’ve done books like that, but it’s different when you’re talking about creating your own comic. Especially for me, because this was the first big thing I had done since Scalped, which was sixty issues. So I wanted to start with that relationship and figure out what the book was from there. There’s always been something organic about it.

And like you said, there’s a lot more to it when you’re doing your own book because of the business side. Basically, we started a small business with this comic. The good part about doing a book at Image is we get to do everything ourselves. They didn’t even know what the hell it was until we turned the book in. That’s cool in that there are four or five of us in a proverbial room putting this thing together and sending it out into the world. The downside is we have to do all that shit ourselves. If a decision has to be made, we have to make it. We’ve built this business together, and that’ll be the case for years. I always say [to Latour], someday my kids will be in business with your kids.

JL: The analogy I always use is working at Marvel is like working in the restaurant industry. You might be the greatest chef in the world, but you still work for the restaurant. When you create your own comic, you own the restaurant. So you can be a great chef, but if you’re no good at running a business, the restaurant closes down. It’s interesting that our book is about broken relationships, and we’re sitting here giving a speech about how our strong relationship is essential to creating the comic.

JA: I think every book I write is about broken relationships. I don’t know what that says about me. I’m happily married, I get along with my kids, but every book of mine is about terrible fathers and ruined relationships.

TF: Are you guys fans of the show Deadwood?

JL: Oh yeah, I’m a big fan.

TF: Me, too. I actually have a friend on the show, W. Earl Brown, who plays Dan Dority. I got to be an extra in season two. I’m picking up a prostitute in the Bella Union.

JL: That’s amazing.

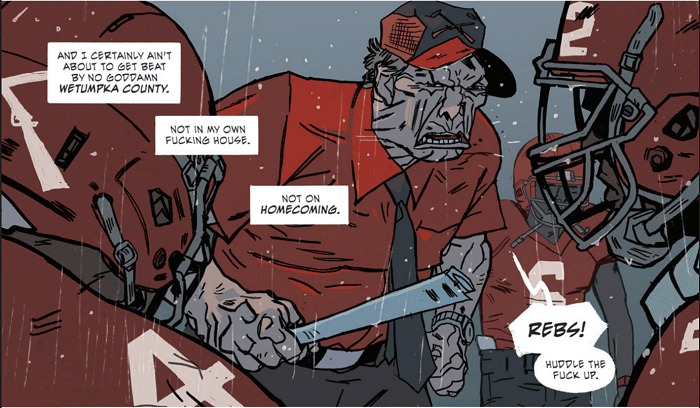

JA: Clearly, I’m a fan of villains like Al Swearingen. The first thing he does in the show, in episode one, is try to murder a little girl. That’s your first impression of Al. By season two you’re like, Oh wait, I really like this guy. To take you on a journey from hating a villain to feeling for him, that’s something we’ve tried to do with Coach Boss. He’s pretty awful in that first arc, and while the second arc doesn’t necessarily make you root for him, you certainly understand how he got there. You feel for him, at least as a kid, and what he went through. To me these are the most compelling villains. The ones who, issue by issue, arc by arc, sometimes even page by page, you wrestle with how you should feel about them. Do I want this character to succeed or not?

JL: I was thinking about this last night as I was drawing Coach Boss. When you work on a Marvel comic, let’s say Spiderman, you hope to leave your mark on the hero. It’s what the whole business is built around, telling the stories of heroes. But our book is about a villain. It’s nice to explore the flipside of the same coin. It’ a healthy thing, creatively.

Early on I felt like I was more connected to Earl. I felt an authorship with Earl that I didn’t have for Coach Boss. But that changed as we started to tell his backstory and made him an ex-linebacker. I played high school football and, if nothing else, he taps into my memory of being surrounded by a bunch of people who I often aggressively disagreed with. Then you got to hit and tackle them everyday.

There’s always something autobiographical in what I write. I don’t have anything in common with the characters in a this-happened-in-my-life, this-happened-in-their-life, this-is-how-I-feel, this-is-how-they-feel sort of way. But there are things about yourself that you can tap into by reading the characters you’ve created. Everytime I go back and look at Coach Boss’s story, it seems like some weird fantasy, like an evil alternate reality where I could’ve ended up.

JA: Like you would’ve turned into Coach Boss?

JL: I probably would’ve been far less successful.

JA: You were just one gunshot in the foot away from being Coach Boss. [Laughs]

JL: Maybe that’s what I would’ve needed to be a much better football player.

TF: One more question for each of you. I guess I should say “for y’all,” talking to Southerners. Jason Aaron, you say in your bio that you love the South but you never plan on moving back. Why?

JA: One thing I’m writing about in the book is a love/hate relationship with the place I came from. I like where I grew up, I like how I grew up, I like being from a small town. I like what that made me, even if I didn’t enjoy every part of the journey. I still go back to Alabama. My family is still there.

But in many ways I don’t belong there anymore. I recently watched Springsteen on Broadway, and he talks about how there’s nothing like being young and leaving home, leaving everything you’ve ever known and going where-the-fuck-ever. If I hadn’t done that, I wouldn’t be doing what I do now. I’ll always think of myself as a Southern writer, even though I’ve lived outside the South now for nineteen years. I don’t foresee that part of me going away, but at the same time I don’t ever see myself going back. I think where I am now and how I got here as a result of me leaving the South. I’m still Southern enough to talk shit about the South, though, in the way that only Southerners are allowed to do.

TF: It’s a hard thing to explain, how it can be so good and so bad at the same time. You probably have, as I do, uncles who have racist tendencies and at Thanksgiving you have to roll your eyes and leave the room.

JA: [Laughs] I have a few of those uncles, yes. Pretty much every Southerner we talk to—and even people we hear from outside the South who grew up in similar places—they get it. That idea of loving a place and being terrified of it at the same time. We get letters from people who grew up in northern England and Australia who say, “Oh, this feels like where I grew up.” Which is so cool when you’re doing something that for us feels very personal, very much about where we’re from. You ask yourself, Is anybody gonna get this? Is anybody gonna like this? Does anybody want a story about crime and high school football in a small town? And then to see people respond the way they have has been really unexpected.

TF: Jason Latour, you say in that same bio that you’re still angry at the South. I think I can probably guess why but I’d like to hear you articulate that.

JL: Well, unlike the other Jason, I still have the guts to live here. [Laughs]

JA: You don’t have the guts to live on the mean streets of Prairie Village, Kansas.

JL: That’s true. You said something that I think is interesting. You said the story is authentic. I wrestle with that idea a lot because to me it’s emotionally authentic, sure. But the story we’re telling is a total fabrication. It’s a dark fairy tale, but emotionally and intellectually the story is honest. Or we strive to make it honest, rather.

I live in Charlotte, which sits on the border between North and South Carolina. It’s a strange place for me, even though I grew up there. If you were to look at a photo of Charlotte in 1977 and a photo of Charlotte in 2019, it would be unrecognizable. It’s the difference between those Gator McKlusky towns and the futuristic cities in Bladerunner. It looks completely different. I left in my mid-twenties and lived all over the country. I lived in New York, I lived in Atlanta, I lived in Florida. I came back, in part, because I knew I had some unresolved issue with living here. I could never quite figure out what it was. I’m really close to my immediate family, but I always felt like I was from a place that didn’t foster any of the things I was interested in. To this day I feel that way. There’s a small arts community in Charlotte, hopefully a growing one, but it doesn’t feel like a place that engenders creativity. One reason I keep a root here, other than my family, is that I think it’s important for artists to represent this place in some way. And show that it’s possible to succeed. That’s a little egotistical but representation matters.

TF: When I was a kid in Clark County, Alabama, I’d go to Grove Hill, the nearest town, and buy all the Marvel and DC comics. I would look inside, and they were published in New York and that seemed as far away to me as Mars. There was no way in hell that a guy from Alabama could ever go to New York and write comic books.

JL: When I finally got a paying job, after what for me was a self-imposed struggle to make it in comics, I was already thirty years old. It was a result of me picking up stakes and moving to New York. I was twenty-nine the first time I went to New York. I can relate to that story from Bruce Springsteen on Broadway, but in a different way. There’s the part when he talks about how exciting it was to get away and travel the world, but there’s also the part about how he lives five minutes from where he was born. I literally live half a mile from where I was born. My town feels like a dream where everyone has a different face. You recognize little parts of it but the faces have all changed. Today Charlotte is a modern city, but occasionally I’m reminded of things I grew up with. My mother’s from rural North Carolina, so we spend a lot of time out there. You see evidence of modern life creeping in at the edges. You might be inundated with people who work for Bank of America all day long, but every now and then someone will speak in a way that reminds you of growing up.

That’s a long answer, but my point is I have a conflicted relationship with the South. So many places have become gentrified. I’m conflicted about the fact that we’ve changed so much as a region. Much of that change has come from selling off the good parts of our culture, rather than the bad parts. It doesn’t feel like an active change. I think I live in, for good or for ill, what’s becoming a new South. I can’t promise I’m going to live here forever, I might not live here in six months, but I like having some authorship over what it can become.

TF: So when are the new issues of Southern Bastards coming out? When do we get more?

JL: Hopefully by the end of the year. Maybe around football season. At this point we’re coming off a hiatus. I don’t have a good excuse, other than it’s a difficult book to work on. I’ve had some personal stuff going on. Jason and I are both very busy outside of the comic. The hope is that when we come back we’ll have enough chapters to stockpile so there’s less of a delay with the next volume.

TF Has there been any option for film? HBO, I think, could make a beautiful production of this.

JA: Yeah, it got optioned a couple of years ago. It’s been in development with producer Scott Rudin and FX. That’s still moving along, nothing I can really talk about. We’ve been involved and continue to be excited about where things are and where they’re going. Who knows. We might have a TV show before too much longer which would be cool. Maybe we can get cameos soliciting prostitutes.

[Laughter]

JL: Or playing them. ![]()

Jason Aaron is a comic-book writer best known for his work on the critically acclaimed crime series Scalped for Vertigo Comics and the Eisner-nominated Southern Bastards from Image Comics, as well as for various celebrated projects with Marvel Comics. His current work for Marvel includes the creation of the headline-grabbing female version of Thor and the launch of an all-new Star Wars series, the first issue of which sold over one million copies to become the best-selling American comic book in more than twenty years. Aaron was born in Alabama but currently resides in Kansas City.

Jason Latour is a comic-book writer and artist. His current projects include co-creation and art duties on Southern Bastards, a 2015 Eisner nominee for Best Continuing Series, at Image Comics, as well as scripting and co-creating Spider-Gwen at Marvel Comics. In 2015 he won the National Cartoonists Society’s Reuben Award for Best Comic Book Artist. Charlotte, North Carolina, is where he learned to draw.

Tom Franklin teaches at the University of Mississippi’s MFA program in Oxford, Mississippi. He is the author of a collection of stories, Poachers, and three novels, including Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter, a New York Times bestseller. His most recent book is The Tilted World, cowritten with his wife, Beth Ann Fennelly.