The previous summer, Ralph and Chris had sworn to run together every morning in hopes of losing their baby fat. It was their freshman year of high school. Stories of eternal virginity and ostracism blurred their perceptions. They were anxious about transitioning from a small Catholic middle school to a large regional high school.

The plan had worked for two weeks before Ralph took up with a girl from a different neighborhood, abandoning Chris to his trails and desired weight loss goals. But the romance flared out in months, months Ralph swore he regretted, apologizing for the injury it caused their friendship, the distance he’d placed between them.

“Hey, love’s weird. I get it,” Chris said, pushing his hair out of his face as they sat on the front steps of their school. “Just don’t do it again, okay?”

“I’m not planning on it. Unless the next one’s way hotter, or plays bass or something,” Ralph replied.

Chris punched him in the arm. Ralph flinched, but only slightly. Ralph was taller than Chris, tan from the summer sun, hair shaved short. Chris was more compact, narrow jawed, plastic-framed glasses correcting astigmatism. They wore T-shirts with the names of punk bands written across the chest, Dickies work shorts, and skateboard shoes.

“Next summer will be different,” Chris promised, recalling the three months he had spent alone, the dark places his mind had wandered. Chris had no other friends. When Ralph wasn’t around, he felt bisected, half-made, a phantom limb grasping with fingers no longer attached. They’d been together since first grade. No family member could boast the closeness he felt with Ralph. “We’re going to get those runs in and make the cross-country team.”

“Probably have to grow those legs a little longer then. I’ll have my dad build us one of those stretching racks. The medieval ones.”

“How about no,” Chris replied, smiling. “I appreciate the creativity, though.”

![]()

The next summer, after the first month of their running regimen, Chris and Ralph grew bored of their usual bike-path laps, the circuitous route around the dog park. They decided to take to the woods, carve paths through the overgrown forests. Chris’s house abutted acre upon acre of undeveloped land. They traced deer paths between oaks and cedars, dipping beneath vines of bittersweet snaking between trees. When the woods grew thick, they’d change direction, veering around kettle ponds and fallow bogs.

Chris carried a compass. Due south was Route 139. There was no way to truly get lost.

“You ever worry we’ll step into a coyote den?” Chris asked Ralph, trailing at his heels, the summer heat oppressive.

“They’re nocturnal. They’d be asleep.”

“But they’d wake up.”

“Are you particularly quick in the morning?”

“Not really.”

“They’re probably the same. We’d be fine.”

A thorny vine caught Chris in the shins, mid-step, sinking deep. He swore and stopped, gently easing the barb from his raw flesh. Sweat dripped down his face, trickling out of his hair. Ralph stopped a distance ahead, calling back to see if he was all right.

“Yeah, I’ll be fine,” Chris replied, shaking off the sting. He looked up from the tangle of vines, noticing a narrow corridor between a wall of evergreens. “Care for a change of direction?” he asked.

“Hell yeah,” Ralph said. They’d been heading north for twenty minutes, the scenery uniform and forgettable.

The two slowed, pushing low branches from their path. The scent of pine overcame the humid breath of mulching leaves. Their sprint slackened to a jog. The press of trees was claustrophobic, pine needles gritty between their teeth.

When they came out on the other side of the tree-bound wall, the forest thinned. A huddle of moss-covered chimneys stood in an empty field, their cottage counterparts eaten away by time. Chris counted ten in all, some in better shape than others. Cracked pediments, slouching spines, trees growing between the mortar.

Without breaking stride, Ralph ran up to the first chimney, placing his hand on the weathered brick, looking out across the overgrown field.

“Your parents ever mention anything about this?” he asked, wiping sweat from his forehead.

“I doubt my parents ever actually walk in the woods,” Chris replied. “They say it’s where dark things ends up happening. Real puritanical.”

Earlier that year, Chris had refused to continue attending Mass with his parents. It had been a battle waged over several months. Groundings and innumerable repercussions followed. Disciplinary action eventually faded to passive-aggressive remarks about the state of his soul. His parents had given up.

Chris couldn’t sit through the homilies, couldn’t believe the creationist teachings of his earlier academic life. The break truly came when his biology teacher, Ms. Reilly, asked how to identify the sex of a human skeleton. He answered by the number of ribs, Adam having sacrificed one to create Eve. The laughter in the class still stung.

“Well, at least they keep life interesting,” Ralph replied, walking to the next chimney, parting tall grass and clusters of holly saplings. Chris didn’t like the feel of the place. Seeing the chimneys separated from the buildings made him think of abandonment. He’d never understood the idea of leaving a house to rot. The number of homeless people he’d seen lining Main Street in Hyannis made a case against any rational argument.

The small village was ringed with trees. No real road cut into the enclave. Chris felt hemmed in, as if something watched from the tree line.

“What do you think they were growing?” Ralph asked, kneeling by a patch of rough earth, a garden plot likely barren for centuries.

“Corn and squash. That’s what they always grew around here. Potatoes maybe. I don’t know,” Chris replied, skirting the fallow field, attention drawn to a flare of color at the base of a distant chimney. It was a wreath of wildflowers, stems twined together, bloodroot and toadflax, lupine and chicory. Unlike the rest of the abandoned village, the garland was fresh, the clippings no more than a day severed. Chris picked up the ornament and breathed in the floral scent, the sweet aroma flourishing in his sinuses.

“Well, that’s out of place,” Ralph said, taking the wreath and inhaling deeply.

“Considering we’re in the middle of nowhere,” Chris replied, knowing they were at least a mile inland from the nearest road. “Yeah, it’s super weird.”

“Leave it.”

“I wasn’t planning on taking the thing home.”

“Good. Your parents might be right about the whole dark-woods thing. All we need now is to see a black goat wandering through the field and we’d have all the makings for a good found footage flick.”

“Blair Witch was terrifying,” Chris added, taking the wreath and dropping it back onto the brick hearth. “I’d prefer to avoid being an extra in the reboot.”

![]()

On the way to church the following Sunday, Chris’s parents dropped him off at the library. A snarky comment about wasted time followed him from the car. Ralph met him out front. The renovated, white-fronted colonial was within walking distance from his house, the path shaded by horse chestnuts and aged birch. The library was open only a few hours. A skeleton crew staffed the front desk. They’d have to make the most of their time.

Beforehand, they’d googled every combination of words that might lead to some understanding of the chimneys. Abandoned village Harwich, MA. Forgotten towns of Cape Cod. Chimneys abandoned in the woods. Every attempt brought disconnected results. None shone light on their recent running route. They’d trekked through the village three times since, on each iteration winding between the brick outcroppings, noting the wreath’s gradual wilt.

Pushing through the front doors, they were confronted by the portrait of Mr. Brooks, the library’s namesake, done in dark oils.

“That guy would have definitely known the answer,” Ralph said, passing by his gaze.

“Or at least pointed us toward the right book,” Chris replied.

The library was all high ceilings and expansive rows of books, mismatched plush chairs and graying carpet. A circular display hunkered in the foyer, exhibiting latest releases and summer reading suggestions. Natural light bled through high windows. One of the librarians directed the two upstairs, to the reference section and computers designated for research.

After another hour of fruitless internet reconnaissance, they abandoned the computers and approached the reference librarian, seated behind a desk lined with encyclopedic texts that looked as if they hadn’t been opened in years. The bearded man’s name tag read JACK.

Chris didn’t know exactly how to phrase his question. He didn’t want it to seem like they were sneaking around somewhere they shouldn’t, or like they were trying to play a practical joke on the man. He always feared such things would make their way back to his parents and they’d forbid him from hanging around Ralph anymore.

As Chris hesitated, Ralph filled the silence. “Do you know anything about a small village out in the woods about four miles that way?” he asked, doing his best to point in the right direction.

“Are we talking Harwich, Chatham, or Brewster?” the man asked.

“Harwich. At least we get to it through Harwich. It might be in Brewster if I really think about it,” Chris answered.

“Well, you’ll have to narrow it down. There were a few villages that didn’t make it through the years out that way,” Jack said, nodding.

“It would have been somewhere a mile or so north of Route 139. Does that help?” Chris asked.

“Actually, it does,” Jack replied, rising from his desk and walking into a row of shelves cordoned off from the public with a velvet rope.

“That’s where they hide the Necronomicon,” Ralph whispered. They’d snuck in a showing of The Evil Dead on their last sleepover. Chris’s parents refused to let him watch R-rated movies, but Ralph’s didn’t care. They thought Chris was too sheltered. A little demon possession wouldn’t hurt.

Jack returned with a thin book bound in cracked leather. “We don’t let people take this one out, and we usually don’t let people take it out of sight. You two can read it over at that table,” he said, pointing to the scarred wooden fixture next to a shelf of periodicals. “Chapter six. That one might make more sense for your purpose.”

“Thanks,” the two said in unison, carrying the book to the designated space.

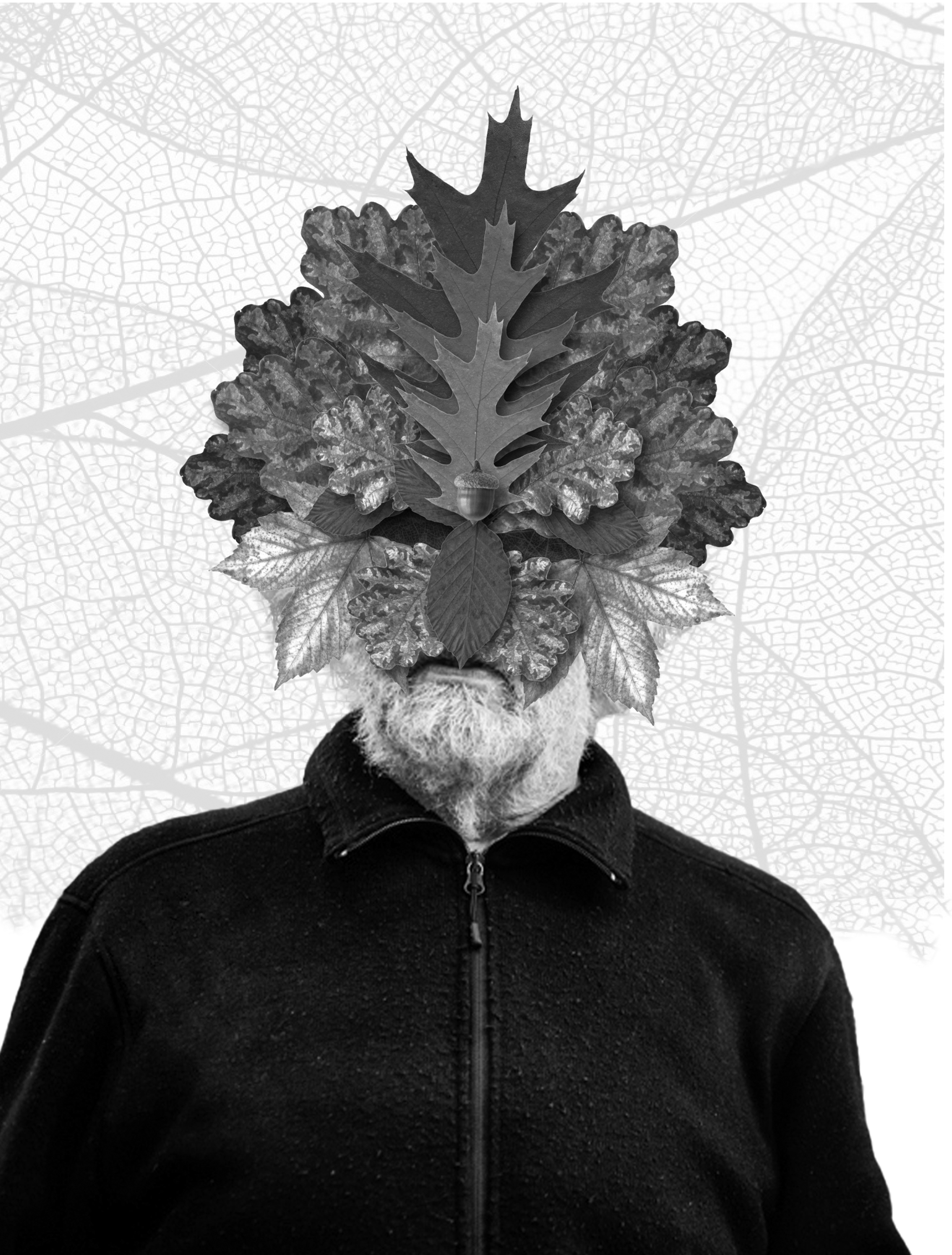

There was no title, just a call number of 974.4 HAR. The early chapters detailed cranberry harvesting techniques, the founding of the first school within town limits, early interactions with the indigenous Wampanoag people, and brining methods using salt harvested from local inlets. The first page of chapter six showed what appeared to be a mask stitched together from dried leaves, the edges overlapping to obscure the wearer’s eyes. The section was titled “Heretics of the Green Thought.”

“Jesus, that’s a terrible name,” Ralph said.

“Really? Is it any better than Peoples Temple or Heaven’s Gate? At least it’s floral,” Chris replied.

“Fair enough.”

The next page showed a charcoal sketch of a rustic hamlet hemmed in by trees, large stretches of tilled soil neighboring each cabin. In the background, the stooped forms of peasants plucked something from the earth, but Chris couldn’t tell what. The subsequent five pages detailed how the town existed outside the surrounding villages, growing its own food, avoiding Puritan churches nearby in favor of pagan approaches to spirituality.

The article said that most inhabitants had been pushed out of the church for their repudiation of strict scriptures. The town of Green Thought existed for almost thirty years before people from neighboring communities started going missing. A total of twelve men and women disappeared from Chatham, Brewster, and Harwich over a two-year stretch. A local vigilante group, members of the church and the loved ones of those lost, decided to search the village and interrogate the inhabitants. It took only two hours to force a confession out of a young man. Second thoughts about abandoning the church plagued his conscience.

The people of Green Thought needed fertilizer to appease their deity, an omniscient presence promising to restore the land to nature, all nonbelievers swallowed by vine and tendril. The crowd unearthed the bodies of two men in a nearby potato field and the body of a woman in an onion patch.

The book didn’t detail the punishment for those who murdered their neighbors, but it wasn’t hard for Chris to guess. They’d read The Crucible in English class. Salem was only a short drive north.

“How does no one talk about this?” Chris asked the reference librarian when they returned the book.

“People don’t talk about a lot of things,” the man replied. “How do you think people believe half of what they do? The answer to most things is out there, people just don’t take the time to look.”

“How did you know where to find the information?” Ralph asked.

“I wrote an article on it for the Harwich Chronicle a few years back. I freelance as a local historian. People love a buried cult story,” Jack replied.

![]()

The next week, they told themselves they’d stay away from Green Thought, but every path through the woods led back to the abandoned chimneys. Even when they swore they’d stick to the bike path, they ended up in the clearing. Chris would take out his compass and scratch his head at the way west had become east, how his directional inclinations fell apart before his eyes. After a time, he gave up fighting, allowing the village to draw them near despite the nucleus of fear blossoming in his chest.

Curiosity always won out.

Sometimes, after they entered the clearing, Ralph would ask if Chris had heard something, tilting his head toward the imagined sound. The words Ralph claimed to hear, the crooning insistence to sow seeds and harvest thistle, never resonated with Chris. It only made him worry about Ralph’s senses, the sway the story held over his friend.

“It’s the power of suggestion,” Chris said as they ran the perimeter of the village.

“It was real close this time. Like the person was next to me,” Ralph replied.

“We’ve literally watched nothing but horror movies for months. When I look into my backyard at night, I see deer skeletons by the shed. But they’re not there. It’s a flicker, confusion between screen and reality.”

“Is that something your parents told you?”

He hadn’t realized he’d regurgitated one of his mother’s aphorisms, one of the reasons she’d been so strict with movie privileges.

“I guess it is,” he replied, before skidding to a stop, nearly twisting an ankle on a rotting log. Where the day before there had been a weed-choked plot of bramble, crabgrass, and mullein, there was now bare earth, freshly turned, raked lines dividing the space into even rows. Chris waited, ready for his vision to realign, carpeting the soil with tangled vines and greenery, but the verdant blanket never rolled into place. Someone had been digging in the garden, getting it ready.

“Still looking for that black goat,” Ralph said, eyes wandering from the tilled garden to the tree line.

“Shut up,” Chris replied. “No one’s bringing a goat out here. This though, this is bad. There’s no reason someone would walk into the middle of the woods to do their gardening.”

“There’s a land shortage,” Ralph replied. “Mom talks about it all the time. Her coworkers have a rough go finding rental property . . .”

“That’s not what I’m talking about.”

“I know, just trying to lighten the situation.”

“Don’t.”

“It’s fine. I’m sure next time we’re out here, nothing will change . . . unless that voice is right. Like you said, no one’s coming out here to grow cabbage.”

![]()

Over the course of two weeks, more and more of the tangled undergrowth around Green Thought was tilled and turned over, exposing rich brown soil. With each lap around the abandoned village, Chris’s stomach gnawed inward, the fear of the book’s citations haunting his mind. The bodies buried in the field, the harvest from neighboring communities. Wasn’t his house one of the closest to the forest? Didn’t his parents forget to lock the doors at night? Chris liked to think he was more mature than his years, but when such thoughts assailed him, he found himself crawling back to infancy, base fears clouding his vision.

He’d been raised on the Bible and all its supernatural logic. Resurrection. Angels. Whale digestion. How was a woodland deity any different from a vengeful God? The thought wouldn’t leave Chris no matter how much he wanted it gone.

“That’s a lot of effort to go through if you’re not going to start planting,” Ralph said.

“It’s too late in the growing season. There’s no way anything’s going to come up,” Chris replied.

“Unless they’re burying something else. With the right fertilizer, who knows? It’s like the voice said.”

“There’s no voice.”

“You’re probably not listening.”

“I am and there’s nothing there.”

“Don’t be so sure of that,” Ralph said, running toward the path leading away from Green Thought. Chris wanted to linger, to examine the soil further, but he didn’t want to do it alone, and Ralph obviously wasn’t into the idea of surveying the site.

![]()

The bones appeared the next week, some whole, others powdery fragments poking through the soil, femurs ground short, clavicles yellowed with age. They seemed haphazard in their arrangement. No care had been taken to hide their presence from wandering eyes. Chris and Ralph stood over the empty plot, the only visible growth belonging to the undead osteology collection. The powdered bones lent a whitened appearance to the soil, mellowing the rich brown it had been before. Chris squatted, retrieving what might have been a minute bone from a human hand, or a leg bone from a squirrel. There was no saying which was which.

“So how are we feeling about the whole not believing thing?” Ralph asked, watching as Chris pushed the bone back into the soil after wiping it off on his shirt. He didn’t want to leave fingerprints in case the authorities stumbled on the clearing.

“These bones are old. Whoever’s doing this isn’t out killing people to fertilize their crop,” Chris replied.

“Maybe they haven’t worked themselves up to it yet. This could be step one, easing into the deep end. Just because you don’t want to believe it, it doesn’t mean you’re right.”

“That’s not it. We don’t even know if these belong to humans.”

“We don’t know they don’t. Regardless, this is sketchy. There’s no reason to bury bones in a garden. This is straight out of that book.”

A flock of sparrows dropped into the glade, some alighting in neighboring pines, others perching on the chimneys, peering down at where Chris and Ralph stood. A shiver passed through Chris’s limbs. The birds focused on them, their tiny eyes moving from the bone-strewn plot to the teenage boys in their running shorts and band T-shirts. Chris felt vulnerable, laid bare. The birds chirped and squabbled before taking wing, leaving the friends to sort what lay before them.

Is that the voice Ralph has been hearing? Chris wondered. The chattering of birds? There was no way to mistake their chitters for actual sentences. He knew he was searching for grounding, something to explain the unraveling reality before him. Nothing was lining up. He couldn’t find his footing.

“Believe what you want. I see a fully tilled field. The book said this was part of the buildup. We both know what their next step is. Either we’re going to do something about this or we’re not,” Ralph said.

“How about we pretend we didn’t see this and run the indoor track after school instead,” Chris said.

“You know that isn’t an option, no matter how much you wish it were. No one else is going to stop this.”

Ralph had always been more inclined to action, less research, more bravado. He didn’t like to wait or ask permission. Chris figured that was why the girl from last summer chose Ralph over him. They were attractive in similar ways since they’d lost weight, minus the height difference. Their interests and hobbies aligned. It was Ralph’s confidence that made him more desirable.

Chris couldn’t bring himself to argue. The dread of pushing Ralph away with disagreement rivaled any leaf-choked Armageddon he could imagine. But he was imagining a leaf-choked Armageddon, so there wasn’t even that.

“So what do you want to do?” Chris asked.

![]()

“Doesn’t this seem a bit extreme?” Chris asked, holding the hand scythe Ralph unearthed from his father’s potting shed. The man was a professional gardener and reserved an entire outbuilding for his soil and spare ceramics. Small seedlings wound pale roots through several grow trays, waiting to be ensconced in a more permanent home. The setting sun crept through the small windows positioned high in the walls, the scent of organic fertilizer acidic and sour.

“If you consider this person’s beliefs, who knows? I wish you could hear what the voices . . . Well, I don’t want a thousand tree branches tapping on my window tonight, asking me to come outside. If they’re planting the bones, then they’re serious,” Ralph said, testing the weight of an axe against his palm.

“And you’re going to be able to swing that into someone’s skull?” Chris asked, gesturing to the axe.

“If it comes to that, yeah.”

Chris had never been good with violence. On the screen it was one thing. In his personal life, not so much. He’d never been in a fistfight, never had his eye blackened over a gym class brawl. Ralph had been a scrapper since they were young. The scar from a dozen stitches traced his left forearm, a reminder of the kid who had tried to steal their skateboards in seventh grade. But Chris had his doubts. The violence Ralph had been capable of was minimal, never something with consequence. Murder was in another category.

“Is it the voices?” Chris asked.

Ralph shrugged. “This is the logical progression of things. These people are coming after our families. We’re going after them. It balances out.”

“And the cops?” Chris asked, his last holdout for resolution aired.

“You think they’re going to believe us about some farm in the woods and a book with no title that exists only at the library? Even if we showed them the body, they’d say it was a hoax or some old deer carcass. No one believes stuff this far away from what they expect.”

“I know,” Chris replied.

Years of listening to punk anthems had made him suspicious of police involvement anyway. He just wanted to keep his hands free of blood and saw no other way to broach the subject.

“Don’t worry. You’ll be the backup. Maybe you won’t even have to use that thing,” Ralph said, clanging the axe head against the curved blade of the scythe. A ringing note sang through the small shed, trilling in Chris’s ears. It reminded him of the sounds of shovels striking stones in preparation for the season’s first sowing.

![]()

They told their parents they were sleeping over at one another’s houses. Their weekends were rarely spent any other way.

Before it got dark, Chris and Ralph tucked their blades beneath black hoodies, ducking into the forest a distance down the road from Chris’s driveway. They couldn’t follow the path they usually took from his backyard. The lie wouldn’t stick.

The setting sun sifted through pitch pines and oaks, staining the leaf-choked forest floor with emaciated shadows, the first hints of fall in the air. A flock of grackles chittered in overhead limbs, their calls reminiscent of unoiled door hinges, rusted and grating. The two moved quietly, not knowing when the second party would arrive. Surprise was the only way. Their pace was cautious, sidestepping brittle sticks and twigs cast off by old growth.

Chris tried to form a complaint, a reason to turn back, but the excuse wasn’t forthcoming. He didn’t want to disappoint. Chris was cautious with his words, the fear of a solitary existence plain before him. His stomach rose into his throat, pulsing with each step, nerves threatening to override conscious thought.

They weren’t turning back.

At Green Thought’s tree line, they paused, scanning the withered village for signs of life. The chimneys cast angular shadows across the unkempt greenery. The garden plot on the far side of the glade had receded further, more bare earth peering through the underbrush, more bones speared up in ragged protrusions. Ralph gestured toward a chimney on the opposite side of the field. It was the closest to the trees and would provide the most cover.

“Stick to the trees until we get there,” Ralph said, gesturing with the axe.

“Yeah, okay,” Chris stuttered, the soft padding of moss giving way beneath his step.

When they were hidden by the blind of a holly tree, Ralph turned to Chris, whose hands trembled.

“It’s going to be fine. You’ve always wanted to be a hero, right?” Ralph asked.

“I mean, who doesn’t?” Chris replied.

“Good. Someone’s always got to be there to brain a zombie or exorcise a demon. Think of it like that. We’re here to stop cultists from taking over our town, or something like that.”

“I know, I know. It’s just hard to imagine the next step.”

“It is. But someone needs to be there before they get too far. When carnivorous plants crawl across your front porch, there’s no hindsight. I’m not letting those things get my parents.”

Ralph fell silent. The trees on the other side of the glade quivered and disgorged a man pushing a wheelbarrow. A leaf-stitched mask obscured his face. He whistled, high and off-key. The wheelbarrow seemed to give the man some difficulty, even though it only contained a minimal assortment of tools. Chris recognized the mask from the pages of the nameless book, the way the leaves wove together to cover the eyes and give the impression of a blank surface.

Chris prayed he wouldn’t recognize the face it hid.

The scythe’s handle was rough in his palm, the wood coarse and unfamiliar. The image of the blade slipping into the man’s chest flourished with each blink of the eye, churning Chris’s stomach.

He turned, ready to run.

Ralph caught him.

“Just wait. It’s not time yet.”

Ralph had mistaken Chris’s flight for an overzealous strike. He’d missed the desperation in Chris’s eyes, the heave and shiver in his chest. He couldn’t hear the chittering scream welling inside Chris.

“A few more minutes and we’ll be set,” Ralph said as Chris squatted, fleeting courage pulling him back to earth.

Then the man removed his mask.

Moonlight fell upon aged features. Overgrown eyebrows swam above a sea of wrinkles. His hair was brushed in a thin comb-over, eyes focused on the patch of upturned earth. Chris nearly dropped his scythe. The man looked like every lonely parishioner he’d seen hunched in a church pew, the priest’s call for thoughts and prayers announcing a sickened spouse. He’d seen the man’s countenance replicated a thousand times in those that were left behind. Those who’d lost the one thing guiding them to draw breath. Chris saw the worry and sadness engraved on the man’s skin, the distance between the world he wanted to live in and the one he inhabited.

“We’re not—” Chris began.

“That man wants your family dead, swarmed by flower petals until they choke. Don’t bail on me,” Ralph replied, clutching the axe to his chest.

“He’s just a gardener. A lonely old man.”

“A lonely old man that’s wearing a cult mask. And the bones. You can’t explain that away.”

“What do you—”

“Even if he doesn’t seem like he’s trying to kill you, he is. Cause and effect. He wants to bury us all in his garden.”

With the last words, the old man stopped unloading his wheelbarrow, looking up from the pile of rakes to where the two boys hid in the holly. His hand drifted to where the discarded mask lay, as if he hoped to hide beneath it.

“Who’s there?” he called.

“Don’t make me do this alone,” Ralph said, stepping from cover, axe raised. Then he was running, full sprint, the weapon before him. Chris was running too, breaking from the undergrowth, following his only friend’s footsteps, scythe catching the glint of moonlight as he trailed behind. The last thought left to him was of Ralph’s body twisted and mangled beneath the roots of an ageless oak, life crushed from his limbs by swelling bark and heartwood. That was the world the old man had painted, the verdant monstrosity he had breathed into life.

The man was feet away.

The scythe no longer felt unfamiliar in Chris’s hand. ![]()

Corey Farrenkopf lives on Cape Cod with his partner, Gabrielle, and works as a librarian and landscaper. His fiction has been published in Catapult, Redivider, Hobart, Blue Earth Review, Volume 1 Brooklyn, Third Point Press, and elsewhere. His work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. His nonfiction can be found in The Coil.

Illustration: J. Hoyt