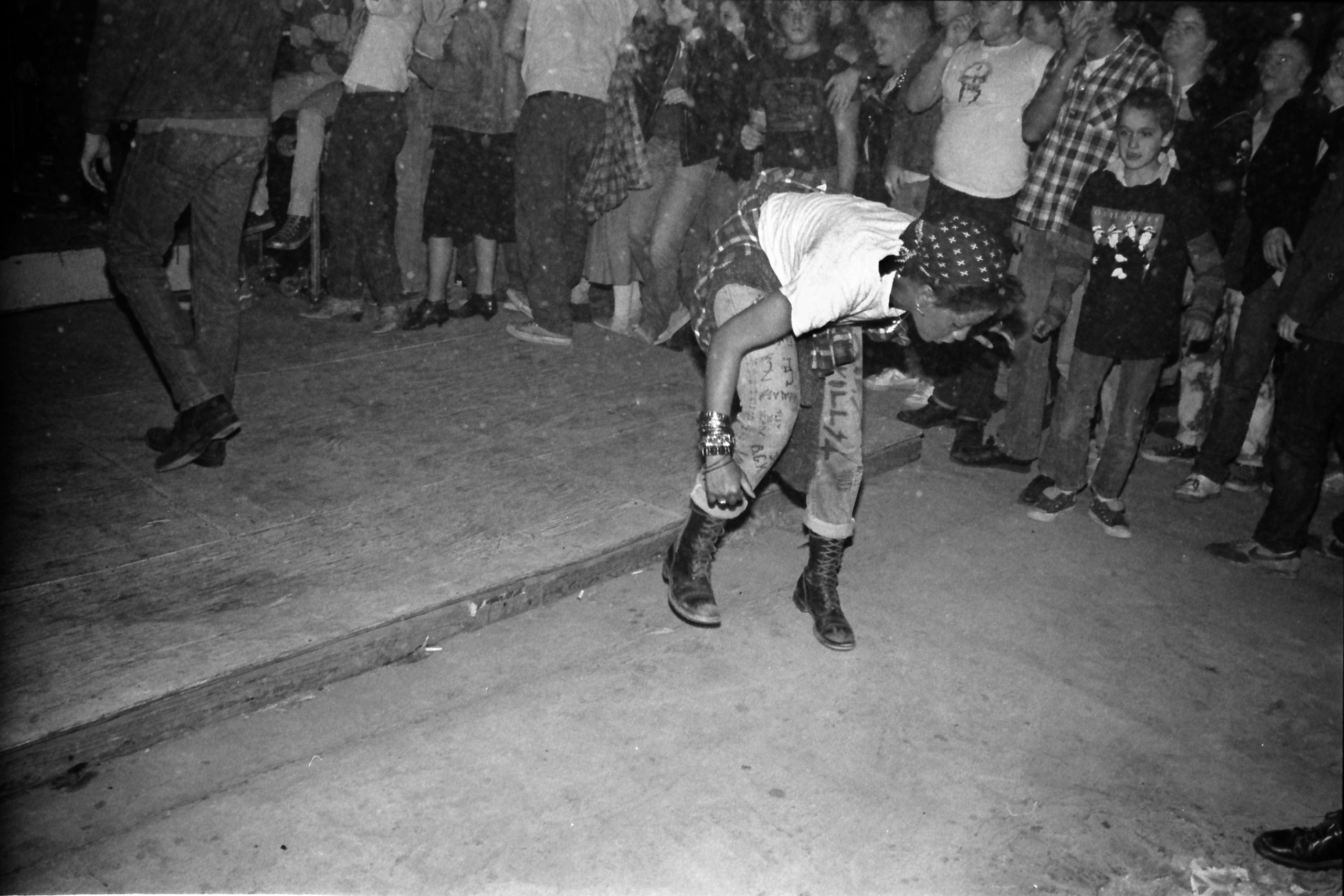

Back at the dawn of time, in AD 1983, I was a Texas teenage punk rock werewolf. And whenever I went to shows by local Austin heroes like the Big Boys, the Dicks, the Butthole Surfers, or the Offenders, I always took my Canon TX 35mm camera and several rolls of Tri-X black-and-white film. This year, Bazillion Points published a collection of my Texas punk photographs called Texas Is the Reason.

When my wife, who is neither Texan nor a punk rocker, got a good look at these photos, she murmured, “White rage.” It was characteristically perceptive: with a few notable exceptions, American punk, especially the hardcore strain, has been mostly a Caucasian thing. Plus, no matter what else is in play—humanism, political idealism, violence, or drugs—punk is always about fury. And everything’s bigger in Texas.

But Lone Star punk in the 1980s was queer, feminist, and more Texican than Texan. We were furious, but what were we raging against? For me, the golden age of Austin punk began with the most woke blast of anti-racism ever recorded, the Dicks’ first single, “Hate the Police.” By drawing a bead on police racism and murder, our most pissed-off band put it all on the table—our self-loathing, our complicity, and our identity as Texans.

Gary Floyd, The Dicks: We were singing songs about what was going on: policemen were throwing people into the bayous of Houston and drowning them. We were singing about the US presence in El Salvador and Nicaragua. Because we were pissed off about that.

Diana Garcia, fan: I loved “Hate the Police”! [sings] “Mommie, mommie, mommie / Look at your son!” I could totally relate to all of that. I didn’t look at the bands and think, “Oh, look at those White people making music.” I thought, “We all speak the same language—the punk language.” The lyrics, the anger, the energy, the wanting something different. There was a reason to be angry. So I saw that the music brought all these diverse people together—from different classes, and different towns.

Gary Floyd: Texans will usually be really honest—even if they’re criminals, like the politicians. They’ll tell you that they’re gonna put you in jail—just for being you.

Roger Manriquez, fan: There was something untouchable about Gary Floyd. He was promoting a lot of pissed-off anger. His songs were deep—like “Dead in a Motel Room”—like, super heavy.

Carlos Lowry, artist: Little Mexico was this apartment building a couple of blocks behind the Varsity Theatre. Some of the Dicks lived there, along with their inner circle of friends, like Santiago, Dolores, and Chuck and Manolo Lopez. Manolo was also in the Perverted Popes. I was painting the mural on the side of the Varsity, and Manolo walks by one day, and he says, “Hey, I have these friends that have a single coming out, and they want someone to do the art.” Then I came up with the idea of having Marx, Engels, and Lenin on one side of the cover, and the Dicks in that same classic formation staring back at them. Gary loved it. It was all done using a Xerox machine down at the post office. It aligned right up with the politics I had.

Gary Floyd: Anger is a part of everything. When you suppress it, you get an ulcer, or you’re vomiting blood. Or you’re a big fucking phony.

Jeffrey “King” Coffey, Butthole Surfers: The Dicks were just nasty, raw punk. The irony is that Gary Floyd was the best blues singer Texas ever produced. When I was seventeen, I took a bus from Fort Worth to Austin. I saw the Dicks at the Ritz. When they launched into “Fake Bands,” it was a sea of people leaping from the stage. And I thought, “Okay, this is the life I want to live.” So as soon as I could, I got the fuck out of Fort Worth.

![]()

To shine a light on race in Austin punk is to see several things. Though we may have thought of ourselves as more liberal—that is, not as racist as other Texans—Austin was a rigidly segregated city, and the faces at hardcore shows reflected that reality. White punks may remember few incidents of overt discrimination, but the handful of people of color who were there tell different stories.

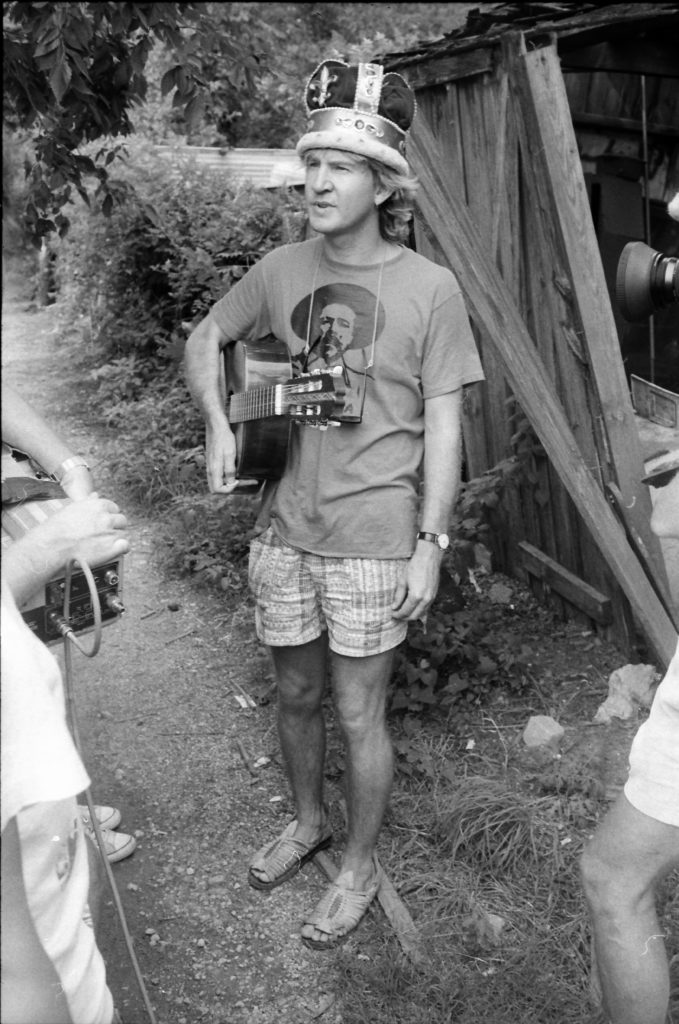

It’s also true that Mexico was in the mix. Raul’s, the first punk venue in Austin, began life as a Tejano music club. Joe “King” Carrasco was the first Texas new wave star, and he mixed cheesy Farfisa riffs with Mexican pop. From the influence of Posada’s Día de los Muertos prints and the ubiquity of Santeria candles in punk bedrooms, to the sheer number of Latinos and Latinas in bands, poster making, and the mosh pit, the Mexican character of the community was more pronounced in Austin than in any other US scene besides Los Angeles.

Garinè Isassi, writer/musician: Walking through the punk scene in Austin was a completely White-person experience. Not only no Black people, but also nobody Middle Eastern, and no Asian Americans. We didn’t think about it because we didn’t have to—we were not living the Black or Hispanic experience. As a “not-exactly-White” person myself—I’m Armenian American—I experienced bias and weirdness in the Texas punk scene, because I would be mistaken for Mexican all the time.

Diana Garcia: I don’t think the Austin scene was just angry White boys. I was angry and I don’t consider myself White. I’m Mexican American. I had a very Chicana culture. I hung out with Minnie, and her mom is Nicaraguan. Minnie was Latinx, Tara was Black. So two of my best friends were not White. I hung out with Harry—Harry wasn’t White. We all had issues, we were all revolting against something.

Teresa Taylor, Butthole Surfers: I had a lot of hatred for my parents. Now I love my parents, but I was a really rebellious teenager. So when I first heard about punk, I went to [Austin record store] Inner Sanctum. I was converted overnight. I thought, “Finally I found some shit I can relate to.” After that, I had the most vivid dream of my life. In the dream, I saw myself putting the needle down on a 45, and it was MDC’s song, “John Wayne Was a Nazi.” And I saw this giant, beautiful Indian chief standing over our suburban swimming pool. He cut himself, then dove into our pool. All the water was blood red. When I woke up, I thought, “This is a racist country.”

Roger Manriquez: I grew up in fucking Vidor, Texas. I worked at a steel plant with all these rednecks, and I’d play my Psychedelic Furs shit [for them], probably Joe “King” Carrasco or some new wave shit. But I had a Mohawk, and they were like, “Why don’t you dye it purple?”

Diana Garcia: Joe “King” Carrasco was fun. I went to a couple of his shows because I loved that song “Party Weekend.” It was really catchy. I liked Rank and File. I thought Alejandro Escovedo was such a babe. He’s good-looking in an unusual sort of way.

Carlos Lowry: Raul’s was a Chicano bar, and Joseph Gonzalez was the manager. I was doing artwork for the Brown Berets and the Austin Committee for Human Rights in Chile. There were at least four events that the group had at Raul’s, on Sunday nights. They were called Pena Folkloricos, and this was in 1978 and 1979, way before hardcore punk and the Dicks. My friends and I got those events together because we had started to go to punk shows at Raul’s, and we’d met Joseph Gonzalez there.

Diana Garcia: I come from San Antonio, from the west side. Went to high school with kids that sold drugs, kids that took guns to school. I thought, “I don’t wanna live in the barrio—I want to go to college and have other opportunities.” And that’s what brought me to Austin. By the time I was in college, I was really angry. And when I first heard Flipper and all this punk rock music, unconsciously I felt like it was about anger at the system. But punks in Austin didn’t understand what really tough neighborhoods were like. That also formed part of my rage. And the fact that I was in class at UT and everyone in my class was White except for me. The only Hispanics I could see were the custodians. I was always very polite to the custodians. My mom was a custodian.

Sammy Jacobo, fan: I used to go to Club Foot for hardcore punk shows on Sunday nights, circa 1983. Because I needed a break from studying and because I was bored. I became friends with Joseph Gonzalez there. We spoke Spanglish with each other, and I only hanged with him at the front door, because I never liked dancing with boys. Some of the music was great. Some of it was horrid. But I never felt threatened by the punks there. I felt more threatened walking on the streets of Austin.

Roger Manriquez: I left Vidor for Austin in 1982. I had a real bad experience. I found my best cousin dead on the Neches River Bridge. It was after we had gone downtown in Beaumont, and we were real drunk. So I was like, “I’m outta here.”

Cathy Criss, singer: [Do Dat singer and guitarist] Byron Scott told me one club wouldn’t pay him for a gig—they’d only agree to pay a White member of his band. I got used to being the only Black girl at punk shows, and mostly nobody bothered me. But my band, the Negros, broke up after skinheads took down some of our posters and wrote “niggers” on others. I got the message that I should just be a fan and not ask for trouble. We weren’t very good anyway.

Diane “Muffy” McGee Hardin, fan: The fact that we can recall a few non-White punks—like Harry, Byron, Alvin, Al, Cathy, Santiago, Roger—says a lot about how overwhelmingly White the scene was. And there were the awful racist skinheads.

Carlos Lowry: In the sixties, the US was coming out of segregation, and the seventies weren’t that much different. I went to college at Southwestern University—there were 2,000 students, and 19 of those were Black. In Austin, White people were scared to cross [to the east side of] I-35. I just think the punk scene here was a by-product of that segregation. On the other hand, in Texas, Mexicanos have just always been here.

Chris Lopez, musician: Go anywhere south of Austin and Houston today, and you will find some of the best non-White punk rock music to ever come out of Texas. Systemic racism has pushed talented people of color out of big cities like Austin for ages, and it’s still happening. In Austin, the White boy bands are still favored to play the weekend shows—people of color only get to play on slow nights. And I can assure you, if it’s not okay now, it was not okay back then.

![]()

Violent skinheads—racist and otherwise—started becoming a problem at Austin punk shows in 1982. Some of the nastiest and most thug-like were fleeing authorities in other states; others were homegrown. Both Roger Manriquez and his friend Tommy Pipes were from Vidor, but it wasn’t just another small Texas town: it was a notorious Ku Klux Klan community near the Louisiana border. Roger, a.k.a. Elbo (short for El Borracho—the drunk), epitomized the contradictions and inexplicable nature of racism in Texas punk. He was everyone’s favorite destroyer: funny, unfailingly drunk, and always ready to jump onstage and sing with any band. Roger was scary, but he lost as many fights as he won. He sometimes spouted White Power notions. He was also Chicano.

Diana Garcia: Roger hung out with these White boys, and we gave him a hard time. We told him, “Elbo, why are you hanging out with them? They’re all White supremacists.”

Roger Manriquez: I didn’t grow up with my culture, I didn’t grow up with the language. As a kid, I used to look at the color of my skin. I’d wake up and I’d go, “What the fuck am I? Am I a White guy or what?” No, I’m not.

Diana Garcia: But the skinheads accepted him, which means they weren’t really White supremacists. Otherwise, why would they be friends with Roger? He’s like, so Mexican American.

Tarbox Kiersted, journalist: I remember sitting outside at Les Amis café one night with Mimi Vitetta, and Roger walked by. He saw us and started chatting. I heard his long and rather involved explanation that Hispanics are actually White, and that they are, in fact, the most superior variety of White.

Roger Manriquez: When I was a skinhead in Austin, to tell you the truth, I always thought I was White. Because I didn’t grow up with all that other shit, people speaking Spanish or saying, “Hey, ese!” I didn’t see myself that way. I grew up around Anglos.

Cathy Criss: Elbo was one of the skate punks who thought it was cool to sport Nazi symbols, although I don’t know if he defaced our posters.

Roger Manriquez: I remember I got into a lot of fistfights. I think a lot of that was just inner stuff. I didn’t really like myself. I provoked it out of my system. A lot of it had to do with a lot of drugs and alcohol. That just fueled it.

Gary Miller, fan: One of the things I liked about punk rock music was that it didn’t matter who you were or where you came from as long as you liked the music. That is, until the Hammerskins from Dallas showed up in Austin. Until I got beaten up by a half dozen of them on a fire escape three blocks above Sixth Street. Not one of them would challenge me individually. I made it my mission to confront them every time I saw a stupid Nazi skinhead in my town. And it wasn’t just me—lots of punk rockers in Austin resoundingly rejected that racist ideology. I got into a lot of fights. I don’t regret it.

Isaäc Valeton, fan: There was a period in the eighties when a certain skinhead was making life unpleasant. He spit on me at the Ritz when he saw my Nazi Punks Fuck Off T-shirt. He made life difficult for me and my friends. He had a platoon of little shitbird skins—a bunch of them beat up my brother and broke his fingers. I got so involved in anti-Nazi activism while I was working at Aaron’s Rock and Roll that one skinhead came in with some KKK guys and took my picture. He told me, “Now the Klan knows who you are. If you fuck with us again, you’re dead.” They ruined a shitload of shows, especially at Liberty Lunch and the Ritz. Other than that, no problems with racists in Austin back in the day at all!

Mikey T. Milligan Jr., skater: I think a lot of that shit was coming out of the California prison system.

Roger Manriquez: I ran with some of the San Francisco Skins. Some of them came through Austin. But they got to be more like Nazis. They got worse. After a while, I kinda got brainwashed by that shit. It got to where I couldn’t even talk to Byron and Alvin, all my Black friends from the scene. And I thought, “Fuck this shit. I’m not even White. I don’t want to be part of this shit no more.” They got so radical. I’m not into no gangs and guns and all that shit.

![]()

Roger and Tommy and the other skinheads loved the Offenders, but so did almost every other Austin punk, whether they were straight, gay, Black, White, or Chicana. The Offenders were the fiercest hardcore band in town, and like the Dicks, they were not college kids. They had emigrated from the west Texas town of Killeen, home to Fort Hood, the most populous US military installation in the world. If any group epitomized White rage, it was them, but their fury was cut with a vast streak of self-loathing. Their sound was illustrated in one of their gig posters: a cartoon close-up of a studded, raised fist.

Jeff Smith, Hickoids: The Offenders were at the nexus of hardcore and punk. Other people made the money, but they made the music. They were harder than hard.

Carlos Lowry: What did the Dicks, the Offenders, and MDC have in common? They were all hardcore, and they were all angry. By the time the Offenders got bigger, it was really speed metal, really thrash, really another evolutionary stage of hardcore. There’s definitely a left-wing, anti-authoritarian thing in the Offenders—but it’s less political, more personal.

Pat Doyle, Offenders: In Killeen, the Runaways and cool Austin punk bands like Terminal Mind played at a hesher’s bar called the Crazy Horse Saloon. Our friends the Ideals would open all these shows with sixties covers and originals like “FTA [Fuck the Army],” which were intended to piss off the local GIs. After Killeen, Austin was Shangri-la—and not just for schlubs like us from small-town hellholes. Austin had pretty, young people, trees, swimming holes, and a real-deal punk rock scene.

Teresa Taylor: The Offenders were good at distilling really large ideas into one-liners. “I Hate Myself” was profound. I could not believe that someone had distilled everything that I was starting to feel, everything that I was going through, and put it in that one line, “I hate . . . myself!!”

Pat Doyle: [Offenders singer] JJ was an abused child who left home at fifteen and earned his street smarts early. He built up a lot of self-confidence as a singer, but I think his hostility to societal norms and laws was well established before he met us.

Teresa Taylor: Onstage, JJ was scary. In person, he was a jokester, such a happy guy. I was talking to him one day outside of their practice space. He had shaved his head and his eyebrows, too. And then it started raining heavily. JJ said, “Ahhh, shit!! I got water in my eyes!” So I said, “That’s why God gave you eyebrows.”

Pat Doyle: JJ’s lyrics didn’t leave space for much interpretation. “Fight Back” is a universal theme of resistance; “Like Father Like Son”—the familiar cycle of family and societal violence; “Face Down in the Dirt” . . . these are raw proclamations of power that strike a chord with anyone who’s ever had their oxen gored.

Teresa Taylor: [Buttholes guitarist] Paul Leary had a thing about Tony Offender. He said, “Watch his big toe on his right foot when he’s playing a really intense solo.” And I looked, and Tony Offender’s big toe came up through a hole in his boot. He’d worn a hole in his boot from playing guitar so intensely. Paul just said, “That’s a really good guitar player.”

![]()

In some of the other Austin bands, rage mutated into outrage, into a penchant for shock and humor so black it was akin to cruelty. The Huns, the most sensational of the early Raul’s bands, paid tribute to something many Texans would rather forget: the assassination of President Kennedy in Dallas in 1963. And beyond their political provocations, the Dicks goaded audiences with scatological tactics borrowed from the John Waters star Divine. Fans of both bands responded in kind.

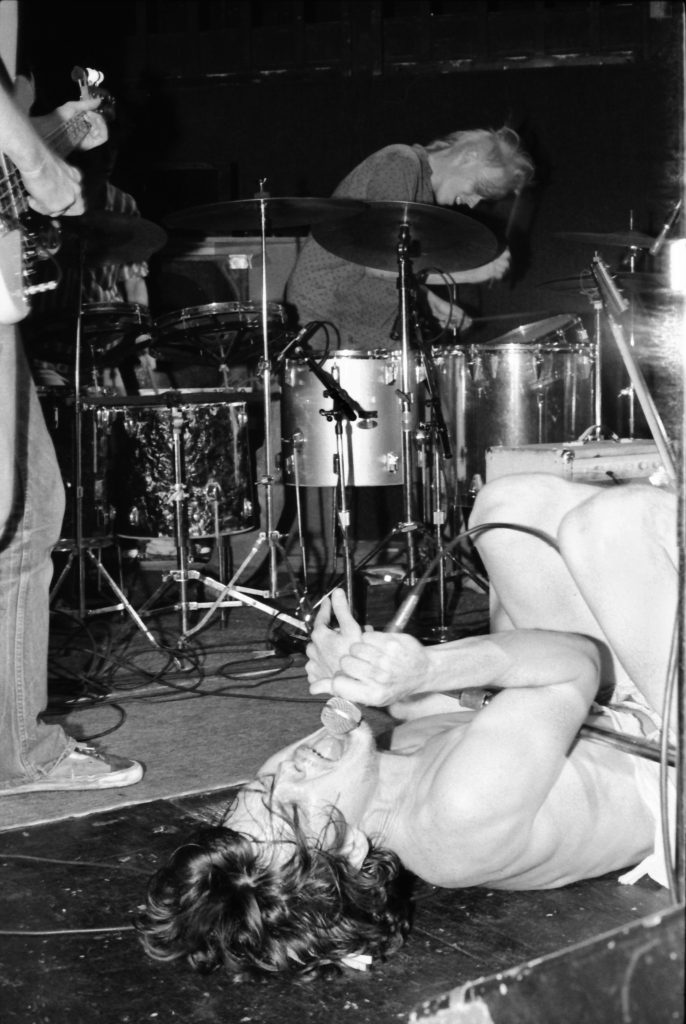

But this weird sideways incarnation of anger as madness peaked with the Butthole Surfers. Their lysergic squawking—with bent saxophones, fake blood, and riffs borrowed from Black Sabbath—was almost unrecognizable as punk, and after years of international touring, they became the most notorious band in the USA. Inspired by both hardcore and 1960s Texas psychedelic band the Thirteenth Floor Elevators, they were possessed by a regional, quasi-Dadaist impulse to defy musical norms and basic notions of human decency. Not everyone got the joke.

Teresa Taylor: I was a Huns fan. I love their song “Glad He’s Dead.” I mean, I loved John F. Kennedy, and Jackie, and John John, too. I always had a reverence for that family. So when the Huns sang, “I’m glad he’s dead / I helped Lee Oswald shoot him in the head!!” it seemed sacrilegious. But I loved the fact that nothing was safe.

Clair LaVaye, fan: I liked their total immersion in irony, cynicism, and wickedness. My partner, Sarita, and I won a radio contest after the Huns said they would perform a song with the contest winner. When we showed up at Raul’s for the performance, the Huns were surprised that we were in costume. We were both covered in fake blood and dressed like Carrie at the prom. We had a feather pillow and a huge knife. That night, as Sarita held the pillow to her chest, she yelled, “But Momma, it’s just a dirty pillow!” I stabbed the pillow. She screamed like Yoko Ono on fire. An explosion of feathers obscured the view. It was a crowd-pleasing performance.

Steve Collier, Big Boys: I remember the Dicks show at Raul’s where Gary Floyd was dressed as Divine. He had stuffed raw liver into his panties. The liver was coming down his thighs. He threw it at people.

Gary Floyd: I was inspired by the heat in Texas. Because I wanted to be cool. And I was infuriated by the fucking heat.

King Coffey: When I first saw the Buttholes, they were playing “D.O.A.” [by 1970s Fort Worth acid rock band Bloodrock]. And it was sooooo great! So when I was invited to join the band, I felt like I’d won the punk rock lottery. I was living my dream.

Roger Manriquez: You couldn’t get any freakier than the Butthole Surfers. I thought, “What happened—did Pink Floyd go punk or what?”

Paul Leary, Butthole Surfers: When I was in fifth grade, I had a band called the Crowd Pleasers. But that was not my first band. I played in one in second grade at a talent show in front of the whole elementary school. We played “Steppin’ Stone,” and I didn’t stop at the end. I kept playing until the other guitar player came up and waved his hand in my face. It was real embarrassing.

Teresa Taylor: We salvaged beauty from an immersion into the depraved.

Paul Leary: There was one night when Gibby got stabbed by a crazed woman in Canada. He did some lyric about a “crippled midget lesbian boy” and somebody took offense. It was kind of hard to tell what happened because of the strobe lights and smoke machines. It all looked pretty weird.

Gibby Haynes, Butthole Surfers: I got stabbed in the arm, but we played it up a bit later. People thought I had been stabbed in the intestines and would have to pee in a bag for the rest of my life. Stabbings are always good.

“The coolest record ever made, this unbridled, surreal burst of imagination is enough to erase years of indoctrination by schools and television viewing. It’s finally okay to do whatever the fuck you want. We can only go up from here.”

—Bruce Pavitt on the Butthole Surfers album Rembrandt Pussyhorse, The Rocket, July 1986

King Coffey: The Buttholes were known as a moronic, drooling, knuckles-on-the-floor sort of band, but Gibby and Paul were essentially art students who were unafraid of everything. We were doing Texas “drag”—we’re from Texas, it’s fucked up, we’re here. We’ll wear trashy clothes onstage. We’ll play all the tropes of Texas to pay tribute to our culture, because it’s our birthright. But as punks, it’s also our right to destroy it.

Teresa Taylor: And there was that show that we played at Voltaire’s Basement as the Jack Officers. At the peak of the show, [Scratch Acid singer] David Yow ran up and smashed a bottle over Gibby’s head. Blood everywhere. El Borracho—I mean, Roger—jumped onstage and said, very sentimentally, “Don’t do that to Gibby!” Then he punched David in the face. They all took David to the ground and were beating the shit out of him. They thought they were defending Gibby, so that was touching. But it was all a setup. Gibby had gone to a theatrical prop store and gotten a Jack Daniel’s bottle made out of hard sugar. Before the show, he gave it to David and said, “Make sure everyone sees you guzzling this Jack Daniel’s, and act super drunk.” I was in on it, but not everyone realized this was gonna happen. So it was hard to explain to everyone afterwards that it had been planned. People got mad.

![]()

One September night in 1984, all of this bad craziness, rage, and anti-racism erupted at once in the middle of a mosh pit at Liberty Lunch. But instead of the Dicks or the Offenders, one of Austin’s most beloved bands was onstage. Ironically, the Big Boys were also the “Blackest” Austin punk group: they incorporated funk riffs into their sound, covered Kool and the Gang, and were a huge influence on an up-and-coming California band called the Red Hot Chili Peppers. The opening band that night was Samhain, the new horror punk group led by Glenn Danzig, the warped genius behind the Misfits. The show got off to a good start, but then something happened out in the crowd. . . .

Tim Kerr, Big Boys: It wasn’t meant to be our last show. There was a lot of shit going on within the band, and the last couple of shows had been really intense. [Big Boys singer] Biscuit and [bassist] Chris were absolutely not getting along, which had nothing to do with the music. It was just human nature.

Dotty Farrell, Technicolor Yawns: This Nazi recruiter had been hanging around Austin for months, giving pot and pamphlets to some of the younger kids. Most of these kids were idiots, and they were already destroying the scene at that point.

Tim Kerr: Biscuit saw the guy standing in the crowd, and he pointed him out, and he said to the crowd, “Hey, that guy down there is a Nazi, that guy’s trouble, there he is, fuck him up.” And standing by him was this smartass kid who had ruined so many places for us. And he was smirking and Sieg Heil-ing us, which pissed me off. So I said something like, “Yeah, and there’s Seth too, he’s part of it.” Or, “Get ’em.” Then boom—we went into our song “No.” And it was like throwing meat to a bunch of dogs. Everybody was trying to beat up this guy.

John Slate, Xiphoid Process fanzine: I was way in the back. The Nazi guy looked like Paul Bartel in a beret, and he was lucky. I prefer peaceful resolutions, but racists deserve everything that’s coming to them.

Bill Anderson, Big Boys roadie: I was on stage left. The Nazi guy was undoubtedly an asshole, but I hate a mob worse than anything. I felt like [Big Boys’ roadie] Jim Straightedge and I were the only people in the entire room who saw what was going on and tried to stop it. A brief whirlwind of violent insanity. I ushered the Nazi guy out—he looked dazed and glad to be alive. I wouldn’t have cared if one guy went up to him and started something, but it was a melee.

Tim Kerr: Afterwards, I remember sitting in the hallway on the floor and just feeling sick to my stomach. And Glenn [Danzig] told me, “Aww, that shit happens all the time in New Jersey!”

Steve Anderson, Cry Babies: I had the unenviable bad luck to be in the room after the show when the band met to decide its fate. I was crushed.

Tim Kerr: It was really disturbing that what happened happened, and it was really disturbing that Biscuit absolutely would not admit that he’d said, “Fuck him up.” It was just that whole thing of not wanting to take on the responsibility. That was the straw that broke the camel’s back. I’m really proud of all that the Big Boys were saying. But I thought, “Jesus, I just want to do something and not have to worry about taking any kind of responsibility at all.” So when Mike Carroll and I started Poison 13, we thought, “Let’s just sing about fast cars, dying, and people in graves—nothing that anybody can follow.”

Gary Floyd: It was very sad . . . very, very sad.

Paul Crow Willis, Agony Column: It was like the whole scene was starting to implode. The Big Boys had always been the glue. Things were certainly different after that. ![]()

Pat Blashill is a journalist and photographer living in Vienna, Austria. He is the author of Texas Is the Reason, a punk rock photobook published by Bazillion Points. He was born and raised in Austin.

All photographs by Pat Blashill.