The front desk clerk, an overweight Mexican with a gout-ridden foot, was reading the sports section of the Reno Gazette when a man entered carrying a suitcase and a large duffel bag. The man, forty-six and wearing a gray suit, had bloodshot blue eyes and brown hair and stood nearly six feet tall. It was eight o’clock on a Tuesday night and he set his bags down and leaned into the front desk counter of the third-rate residential hotel. He wiped the sweat from his forehead with his coat sleeve. “Do you have any vacancies?” he asked.

The clerk nodded.

“Somebody told me you have the old type of bathtubs.”

“We have clawfoot tubs in some rooms.”

“That’s what I want,” the man said and again wiped the sweat from his face. “A room with a tub like that. Do you have any of those?”

The clerk looked through his book. “How long are you staying?”

“I’m not sure.”

“It’s a hundred and seventy-five a week. We have cheaper rooms but not with tubs.”

“I’ll take a room with a tub.”

“What’s your name?” asked the clerk.

“Walt Collins,” he said and took out his wallet. Inside it was a library card, a few scraps of paper with phone numbers written on them, a driver’s license, and $363. He filled out the paperwork, paid the man for a week, and was given the keys to a room on the fourth floor. By the time he made it up the stairs with his two bags he could hardly stand. He unlocked the door and went inside. He dropped the luggage on the floor, pulled back the thin, stained bedspread and blanket, took off his shoes, and lay down on his side, pulling his legs up to his chest. He took a bottle of antacid tablets from his coat, ate five, and closed his eyes.

Thirty minutes later the pain in his stomach ceased and he sat up. He looked over the room. The walls were a smoke-stained white and the carpet was brown and threadbare. There wasn’t a TV, only a bed, a wooden dresser with a brick replacing one of the legs, a lamp, and a bedside table. The bathroom was tiled and had a clawfoot tub, a toilet, and a sink. None of it had been cleaned properly. He took a notepad from his coat pocket and wrote: Get cleaning supplies and a bath towel.

He sat back on the bed and began writing what he’d left at the woman’s house but none of it seemed to matter anymore except for his records. He’d have to get those back at some point but the truth of it was he wasn’t even sure he cared about music anymore. Maybe a person becomes too old for music. Maybe a person gets so fucked up that after a while, more than anything, they just want silence. He rinsed his face and left the room.

Outside the entrance of the old brick hotel, he smoked his last cigarette and went to the mini-mart next door. Against the back wall he noticed shelves of used paperbacks. He picked up a John D. MacDonald novel called A Deadly Shade of Gold and bought it and a pack of cigarettes. After that he got a cab to Raley’s grocery store and bought an electric kettle, a toothbrush and toothpaste, a coffee cup, a box of peppermint tea, a bar of soap, a bottle of shampoo, a yellow notepad, a bath towel, a sponge, a can of Comet, a spray bottle of tile cleaner, a toilet brush, and an alarm clock.

At six o’clock the next morning he cleaned the toilet, sink, and bathroom floor. He scrubbed the bathtub twice before filling it. He turned the clock radio on to Sunny 1230—“hits from the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s”—and got in the tub. He took the new yellow notepad and began writing.

GET A SPOON

1. You can’t drink anymore.

2. But if you have to drink, just drink beer.

3. If you have to drink, just drink peppermint schnapps or Jägermeister.

4. No more gambling on football—college or pro. Remember you have to pay rent now.

5. No gambling PERIOD. But if you have to, just horses.

6. Santa Anita as a hobby. Maybe? A limit of $40 a week???

7. Buy new underwear.

8. Don’t see her again. Don’t fuck her when you do see her.

9. Buy new socks.

10. Soda ruins your stomach no matter how good it tastes. No soda. Maybe Sprite???

11. You’re turning into all the guys you’ve ever hated.

12. Get your records back.

He threw the pad into the main room, got out of the tub, dressed, and left.

Hurley’s Used Auto Hamlet sat on a two-acre lot and had forty running cars and fifteen more nearly so. The sales office was a brick 1930s house. Behind it was a Quonset hut where the mechanic worked and behind that a 1970s powder-blue single-wide trailer. The owner, a sixty-three-year-old man named Earl Hurley, was asleep on the couch when Walt came in. He didn’t wake the old man, he just went to his desk, took off his coat, sat down, and began reading the newspaper. The morning crawled by and no customers came. Walt drank cups of peppermint tea and finished the paper and began working on the crossword puzzle. He took a nap at his desk for a half hour. By late afternoon, Earl was up, and only two customers had come onto the lot, both Mexican and Walt didn’t speak Spanish.

The first, a well-dressed man in a black cowboy hat and black leather coat, pointed to a Ford F-150 and began saying things about the truck in Spanish. When Walt stopped him and said, “No hable Espana,” the man shook his head and turned around and left the lot. The second customer looked like an insurance salesman or a schoolteacher. He found Walt and pointed to a silver Toyota Corolla. He smiled and took a roll of money from his sport coat. He tried to speak English but nothing he said made sense. Walt took the notepad from his coat pocket, wrote down a price, and showed the man what he’d written. The man looked at Walt and shook his head. Walt wrote a lower number but again the man shook his head. Walt tried to give him the pad and pen, but the man wouldn’t take them. He just waved his hands back and forth and finally walked away.

When Walt got back to the office, he sat at his desk and sighed. “I really gotta take a Spanish class.”

“It’s good to see you still have ambition,” Earl said and yawned. He’d gone from his desk back to lying on the couch. His cowboy boots were off and an ashtray sat on his stomach while he smoked.

“I think one of us has to learn,” said Walt. “I mean every third customer who comes on the lot is Hispanic.”

Earl took off his glasses and rubbed his eyes. “I’d take a class with you but I think my days of learning anything are over. I mean, I can barely remember the things I used to know.” He put his glasses back on, took the ashtray off his stomach, and stood back up. He walked to the main window and looked out over the lot. There was a plastic comb in his shirt pocket and he ran it through his thin gray hair. He cleared his throat. “You know about six weeks ago my neighbor’s kid came over to my place on his bike.”

“I didn’t know you had neighbors.”

Earl nodded. “They live maybe a mile away. You can’t see them from my house. The old guy who owns the place has arthritis so bad he can’t get around. He’s eighty, eighty-five, something like that. A few years ago his sixty-year-old daughter got divorced and came back to take care of him and, then a year after that her own daughter moved in with her kid, a boy who’s eleven. He’s the kid who showed up. I’m on the couch asleep and suddenly there’s knocking on my front door. It’s eight at night, pitch-black out, and no one comes to my place. If they do, you hear a car, you hear them coming up the gravel road, and if it’s dark you see the headlights from a long way off. I about had a fucking heart attack. I keep a pistol in the cupboard, in my popcorn maker. I take it out and walk to the front door and see the kid. I didn’t know his name but I could place him. Turns out he’s failing out of school. His mom’s never around and his grandmother is nuts. Legitimately nuts. She spent a year or two in the state loony bin on Glendale.

“So the kid’s standing at my front door so nervous he can’t speak. I don’t know what to do and he won’t come in. Finally he just starts bawling. So I call Virg over and the kid likes my dog and it’s the dog that calms him down. Turns out his grandmother wanted him to come over so I could help him with his homework. Since I owned a car lot she thought I was probably good with numbers and put him on his bike. So I invite him in. The kid’s alright, a little goofy but decent enough. Math’s his worst subject. That and English, but it’s math that’s got him on the ropes. He needs help with fractions. But here’s the point: I can barely remember what a fraction is. He’s only eleven and still it takes me an hour to help him do his homework that night. I ended up making him dinner and putting his bike in my car and taking him home.”

“If you get him good grades, you’ll have another son. He won’t ever leave.”

Earl laughed. “He got a B on that assignment. And you’re right, he eats dinner with me three nights a week now. But the thing that I can’t stop thinking about is, I had to get a book on punctuation and a book on basic math just to try and remember things. And I used to know all that sorta stuff. I’m probably the only son of a bitch alive that liked doing homework. I did. I used to help my son with his and then my grandson. Shit, I used to do my grandson’s homework for him. But now I can’t remember anything and I struggle with an eleven-year-old’s math problems. I guess what I’m saying is good luck with Spanish. I think you might have enough brain cells left. But not me. What I’m hoping is they’ll learn English or we’ll start selling enough cars that I can get Javier back and he can deal with it.”

Earl watched an old silver Ford Taurus pull over in front of the lot. A middle-aged woman in yellow sweats jumped out and looked inside a two-year-old VW Jetta. She circled it twice and then walked back to her car and drove away. Earl coughed, put the cigarette between his lips, and combed his hair again. “So let me ask you the real question: Are you going to go back to her?”

“I guess that is the question,” Walt said and leaned back in his chair. “She’s got a great house. I had my own bathroom that had a bath and separate shower. She’s also got a housecleaner and a hot tub and six months ago I talked her into buying a new stereo. The turntable alone cost a grand. I guess if I’m being honest that’s what I’ll miss most. The stereo and maybe her kitchen because it’s always stocked with food. And her cat. A Siamese named Rocko. But . . . Well, she won’t take me back even if I wanted to go back. She’s got a temper and thinks I’m a bum because I work here. . . . Look, I’m sorry we had to take the phone off the hook.”

“If a customer wants to talk to us bad enough, they can come down here,” said Earl. “What about her though? Is she going to come?”

“I thought about that but I don’t think so. I don’t think she cares that much. It’s not like I did anything mean to her. I didn’t cheat on her or . . . That’s why I don’t understand her calling here all day. I don’t know why she’s so mad. I mean I just got laid off at the Mercedes dealership when they sold it. That wasn’t my fault. They brought in their own guys. And then, fuck, she caught me drinking beer in the morning a couple times the week after I was out of a job. She was screaming mad about that. She quit talking to me for a week because of that. . . . Wouldn’t even look at me, and then I started here and she told me to move out.”

“I’m sorry,” said Earl.

Walt gave up on the crossword and set the pencil down. He rubbed his face with his hands. “Yeah, me too. It’s not like she’s worried about the money, it’s just that she doesn’t like the thought of me working at a used car lot. It doesn’t sound good if she has to explain it.”

“I can see that,” said Earl, finishing his cigarette. He moved back to the couch and sat. “I can’t remember if you told me, but how’d you meet her?”

Walt moved his chair around to face Earl. “She came in one day and bought a brand-new black CLS from me. They run about eighty thousand and she paid cash. She had inherited a shit ton of dough from her grandparents when she was in college. That’s why she’s never had a real job. Doesn’t need one. After we did the paperwork, she invited me to dinner in Lake Tahoe. She’s got a cabin there, right on the water. She’s got a hot tub in that place, too. One thing about her, she knows how to live. . . . Anyway, don’t worry. She doesn’t have a gun and she hasn’t been here before so I can’t imagine she’d come now.”

“So where are you gonna live?”

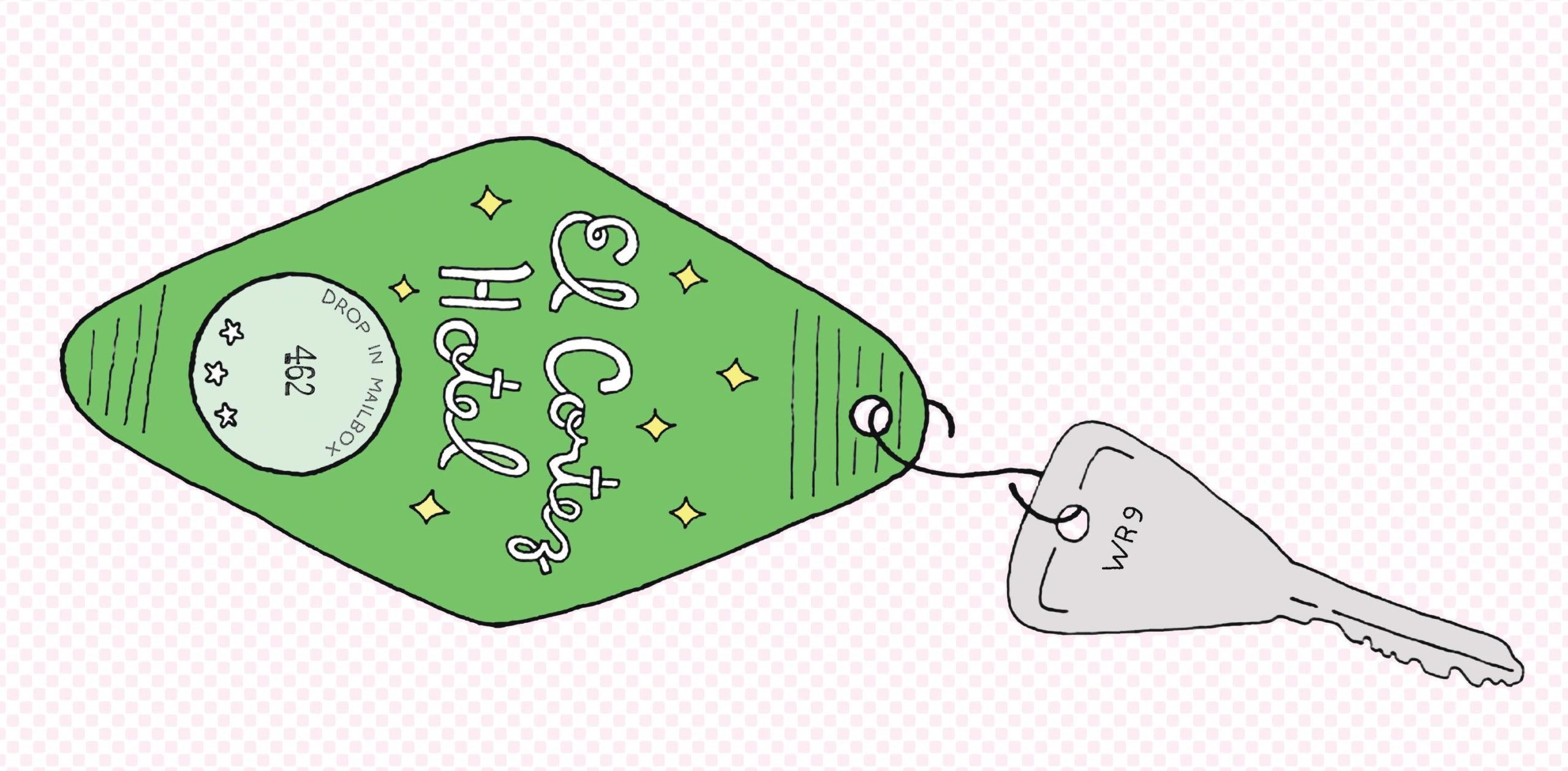

“I just moved into the El Cortez.”

“The old hotel?” Earl cried and stood back up.

Walt nodded.

“Jesus, are you going to hang yourself next?”

“They have bathtubs and it’s the only thing that helps my stomach.”

“That’s a tale of woe.”

Walt laughed.

“But I bet the El Cortez is on a boiler,” Earl said and sighed. He laid back down on the couch. “At least you’ll have endless hot water for your baths.”

“I’ve always liked that about you, Earl. You don’t judge and you always see something on the upside.”

“I gotta say there ain’t many upsides there. Fong’s used to be next door. That would have made it better. That was a great Chinese joint but it’s long gone now. Well, you can always live with me.”

Walt lit a cigarette. “I appreciate that, but you’d have to drive me in and out. I can’t ask you to do that. I like working here and you’d end up hating me.”

“I always forget you don’t drive. The car salesman who doesn’t have a car. So the El Cortez . . . My advice is don’t stay long.”

“If we get some customers, I won’t.”

“I can always give you a loan.”

“I don’t borrow money anymore.”

Earl nodded and looked at his watch and smiled. “Goddamn, it’s time,” he said and turned on the TV to find Days of Our Lives just beginning. He lit another cigarette, put the ashtray on his stomach, and propped his head on a pillow so he could see the TV.

![]()

At five o’clock Earl got into a 1993 silver Cadillac Fleetwood and left. Walt waited another hour and a half but no customers came in. At six thirty he locked the office and began the two-mile walk home. He stopped at Jack’s Coffee Shop for a bowl of split pea soup and a side order of hash browns. He drank two glasses of water, paid the check, and left. But when he passed the Coney Island he couldn’t help himself and went in for a draft beer and a shot of Jägermeister. After that he bought a pint of peppermint schnapps at the Fireside Liquor Store. At the mini-mart next to the hotel he bought a package of Pop-Tarts and went up to his room. He read A Deadly Shade of Gold until midnight and slept until 5:00 a.m. and then got up, sat in the bath, and made another list.

1. Quit smoking

2. Try to get the records back

3. Buy a TV

4. Buy a book on Spanish

5. Get nail clippers

6. I have $130 left

7. Don’t drink today

8. Buy your own sheets, think about where these have been

9. Don’t call her no matter how lonely you get

10. Try not to eat so goddamn much. Try to lay off bacon, lay off cheeseburgers, and quit fries. No more soda. Stop with the Pop-Tarts.

11. She’s right, you are a bum

He threw the pad onto the floor, let half the water out, filled the tub again with hot, and finished A Deadly Shade of Gold. At six thirty he dressed and left. He kept three cigarettes and threw the rest of the pack in the lobby trash can. He walked to the river, smoked the first one, and went across Arlington Street. The sun rose as he walked along Court and he kept going until he came to the woman’s house, a two-story, four-bedroom Tudor Revival built in the 1920s. She had HBO, Showtime, and AMC. She had groceries delivered and took cooking classes. He sat on the sidewalk and smoked his second cigarette. It was the nicest house he had ever lived in and probably would ever live in.

He supposed the real problem of the situation was that he didn’t love her. He was just lonely, felt like shit all the time, and was coming to the slow realization that he had become a failure. And what’s the point of anything when you’re a failure? He looked at his watch, got up, and began the walk to work.

It was just past eight o’clock and he still had a mile left to Hurley’s Used Auto Hamlet and already he wanted a shot of peppermint schnapps and another cigarette. He stopped at a mini-mart and bought a pack of gum and the newspaper. The sun rose over the mountains and he came to the lot. He unlocked the office and made a pot of coffee for Earl and a cup of peppermint tea for himself. He was reading the newspaper when he noticed a young couple looking at a silver three-year-old four-door Honda Civic. He got up and went outside and walked across the gravel lot.

An hour later the girl sat on the office couch drinking coffee while her boyfriend finished the paperwork. He handed Walt a cashier’s check. Walt verified it and handed him the receipts, the title, and two sets of keys. He stood in front of the main window and nervously watched as they got into the car. But once again it started and once again it made it off the lot and down the street. It left and didn’t come back.

He chewed three antacid tablets and was working on the crossword puzzle when a black Mercedes parked in front of the sales office. The horn honked and didn’t stop for nearly two minutes. Walt didn’t go outside. He watched from the edge of the main window. Finally the car door swung open and a middle-aged woman came out. She was tall and thin with blonde hair, mirrored sunglasses, a tight black pantsuit, and high-heeled black shoes. She opened the trunk, took out the thousand-dollar wooden turntable she’d bought him, and threw it as hard as she could. It hit a red Chevy Cavalier and broke into pieces. She struggled with the two crates of records but got them from the trunk and dumped them on the gravel, where they spilled out. She then bent over and began flinging them like Frisbees at the office door. She threw nearly a dozen and then got back into her car and drove away.

Walt lit his last cigarette and walked outside. The ones she’d thrown were all Buck Owens and the Buckaroos records. Ruby was out of its jacket and broken on the gravel as was Sweet Rosie Jones. In Japan! was okay in its jacket on the porch, and Dust on Mother’s Bible was on the office roof, its condition unknown. But they were his least favorite. He couldn’t remember the last time he’d listened to Buck.

He picked through the rest of them until he came to his ten Jack Teagarden records. They’d made it out alright. The jacket edges on a few were bent but he didn’t care about that. His two best Candi Statons were okay, and his favorite Esther Phillips records were fine as was his favorite Sammi Smith, The Best of Sammi Smith double LP. His spaghetti western records, his Armstrongs and Merle Haggards were all okay. His best records had made it unscathed. He was putting them back in the crates when Earl drove up and parked. He got out of his car wearing dark sunglasses, a blue cowboy shirt, and black pants. He was carrying a large paper sack. “So she finally came by?”

“I lost the record player,” Walt said and pointed to it. “She threw it at the Cavalier. Cavalier’s alright though. It just hit the bumper.”

Earl set the paper sack on the Cadillac’s hood, lit a cigarette, and began combing his hair. “I didn’t know people still listened to records.”

“Some people do.”

Earl looked out over the lot. “You sold the Honda?”

“They paid windshield price.”

“Christ,” Earl said and smiled.

“They had a cashier’s check.”

He laughed. “And your woman didn’t shoot you?”

“No,” Walt said and picked up the first crate.

“Little miracles. You always gotta be thankful for little miracles. You hungry?”

“I’m always hungry,” said Walt.

“I got two chicken-fried steaks, eggs, and hash browns. If you hurry and clean this shit up you won’t miss the start of The Young and the Restless.” ![]()

Willy Vlautin is the author of the novels The Motel Life, Northline, Lean on Pete, The Free, Don’t Skip Out on Me, and The Night Always Comes. He is the founding member of the bands Richmond Fontaine and the Delines. He lives outside Portland, Oregon.

Illustration: Josh Burwell is an artist and illustrator from Mississippi currently living and working in Los Angeles, California. You can find more of his work at jburwell.com or on Instagram @jburwell.