Ed Chaney shot Lesser Dunn to death in 1907. This was only a few years after Ed was elected sheriff and his wife succumbed to an affliction of the brain. She had been a kind woman in life, Ed’s Vera, known for her patchwork quilts, but no amount of tongues or hands laid upon her at the Holy Christ Church ever tamed the demon in her skull. Ed’s father, Otis Chaney, who’d sold dry goods across the railroad tracks, was dead a while by then. Ed himself was the father of no children. After Vera was buried, he took comfort solely in the weight of his office, which he bore with the same solemnity and grace as the gold wedding ring he had yet to remove. He never wore a badge, or a gun. But he always wore that ring.

Back then, at the turn of the century, these hills were yet wild and a man could get lost up here and never see home or kin—or himself—again. Back when the ginseng was thick and the water was clear and Lesser Dunn lived in a cave at the top of Black Arrow Rock, or as we knew it, the Bar. We still tell stories about Lesser: How he had a silver mane like a spray of falls down his spine, eyes black as volcano glass. How, if a man was vigilant by light of the full moon, he might spy Lesser creeping out of them trees on all fours to raid some chicken coops. Strip a bird with his teeth, eat its flesh raw. Those kinds of stories.

But this ain’t that kind of story. Not really.

Ed was the only man living in Ransom County who knew the truth about Lesser because Otis Chaney bought whiskey from him when Ed was a boy. Otis took cornmeal and salt pork up the mountain to trade for liquor, and Ed went along at his old man’s heels. Lesser kept mostly in the shadows of his cave during these transactions, venturing out as far as a cusp of shaded rock that overhung the gorge like a swollen lip. There, he just hunkered down, tall and gangly, face overrun by a mossy gray beard. That hair, spilling down his shoulders. He wore overalls smudged with soot and stained in rust-colored patches. His corn-whiskey still, Ed’s father said, was forty or fifty yards up in a stand of spruces, near a running brook. Lesser traded with no one but Otis, who sold the old shiner’s liquor in his dry goods store. I bought a bottle or two myself, back in the day.

Ed was twenty-nine when his father died. Otis was hoeing up a new vegetable garden behind their little clapboard house when his heart just stopped like a clock at three in the morning. Afterward, for a while anyway, Ed kept up the store and the trade with Lesser, carrying bundles of beans and pork and meal all wrapped in butcher’s paper up to the Bar. Lesser barely spoke to Ed, who as a boy had sat on the edge of that great granite slab for sometimes over an hour, waiting on his father to emerge from the dark mouth of Lesser’s cave. Looking out on the land below, hardwoods and hills and meadow balds, marveling at all the things he didn’t yet know.

Once, Ed asked Otis if he and Lesser were friends.

“Much as men like us can be,” was what Otis said.

![]()

In the spring of 1907, a logging outfit moved in and set up its headquarters in Otis Chaney’s old store. The railroad brought strangers in heavy wool coats and fingerless mittens, knit caps pulled down on heavy brows. Soon enough, saws chewed wood in the foothills below the Bar. We all watched from our tin-roofed porches as ancient trees toppled. We mended corn cribs and slopped hogs while the timber cracked. Above us, looming, that bald jut of rock like a knob of gristle and bone. The only part of us that company didn’t want. Somewhere up there was a cave haunted by a creature we prayed the Lord God to loose upon them company men, before the whole of creation fell beneath their blades.

It was a rainy March day, about noon. Ed sat on his porch, tuning up a banjo made from a turtle’s shell. Down the road came a sullen, pimple-faced boy in denim and boots. He pushed through the rickety gate at the edge of Ed’s property and Ed got a look and saw it was the eldest boy of a pig farmer named Spitz. Ed called out a warning as he picked his shell: “My day off.”

“Your sorry-ass deputy sent me,” the boy smarted. He tucked his hands in the bib of his overalls and spat snuff. “I done been to see him.”

“Well, what can I do Ronald Biggs can’t?”

The boy’s shoulders slumped. Most likely, he’d been roused early that morning for chores, made to walk the dusty road into town after a long three hours of milking, pitching, planting. He had a half-moon bruise beneath his eye in the shape of his daddy’s knuckles.

“What’s wrong, Elmer?” Ed said. “You and your sister well?”

Elmer Spitz rubbed his nose and shook his head. “Ain’t that. Daddy said tell you them damned loggers done kilt our hog.”

The boy’s words felled something in Ed. A crack like a great pine giving way, crashing forever to the ground. But he only said, mildly, “Well, I am sorry to hear it. Why would they do that?”

“On account of Daddy won’t let ’em cut up above our holler.”

“Don’t seem like killing your hog would persuade you.”

The boy spat again and met Ed’s gaze. “They done bad things to her.”

It was not a quarter hour before Ed’s horse was clipping along the dirt road up into Spitz Hollow, the boy dozing behind him, cheek warm against Ed’s back. A Winchester rifle was lashed with rawhide cord to the pommel of Ed’s saddle. A pair of rutted tracks forked off from the road and wound up to a mud-daubed cabin. Spitz sat on the rough-hewn steps of the porch, ladling water from a cedar bucket over his shoulders, a pair of red suspenders like fallen wings around his waist. Holding the bucket, eyes red and cheeks swollen from hard crying, was a freckled, plump girl in a homemade dress, thirteen or fourteen.

Ed drew his mount up, let the boy get down, then swung out of the saddle.

Spitz threw the ladle back in the bucket and told the girl to get. To Elmer, Spitz said, “Take the sheriff’s horse out to the barn and give it water.”

Ed took his rifle down before the boy led the horse away. He hung there in the hardpan of the yard, eyes traipsing the encroaching woods, where a veil of mist still clung between the treetops. On the breeze, the stink of hogs.

“Well,” Spitz said. He hooked a thumb over his shoulder. “Best see it for yourself.”

Wordlessly, Ed followed him out past the barn and a patch of newly sprouted squash and tomatoes, past plowed rows that would, come summer, be corn, past several muddy hog pens—one of them empty—then beneath a canopy of pines and cedars, dogwoods and white-blooming rhododendrons.

“Right up here,” Spitz said, pushing aside a fistful of branches.

Ed drew a breath and swallowed a rank, metallic stench, beneath it the damp scents of rot and earth. In the next breath, he saw it, and his stomach rose hotly into his throat. He covered his mouth with his sleeve.

Just up the hill, in a fall of dead leaves, a giant sow lay on her pink, hairy side, stomach slit down the middle, insides heaped beside her on a slab of rock. In a litter about her teats, as if they had burst forth and wriggled back to suck, were the slick, curled shapes of six piglets.

“She’s due any day,” Spitz said.

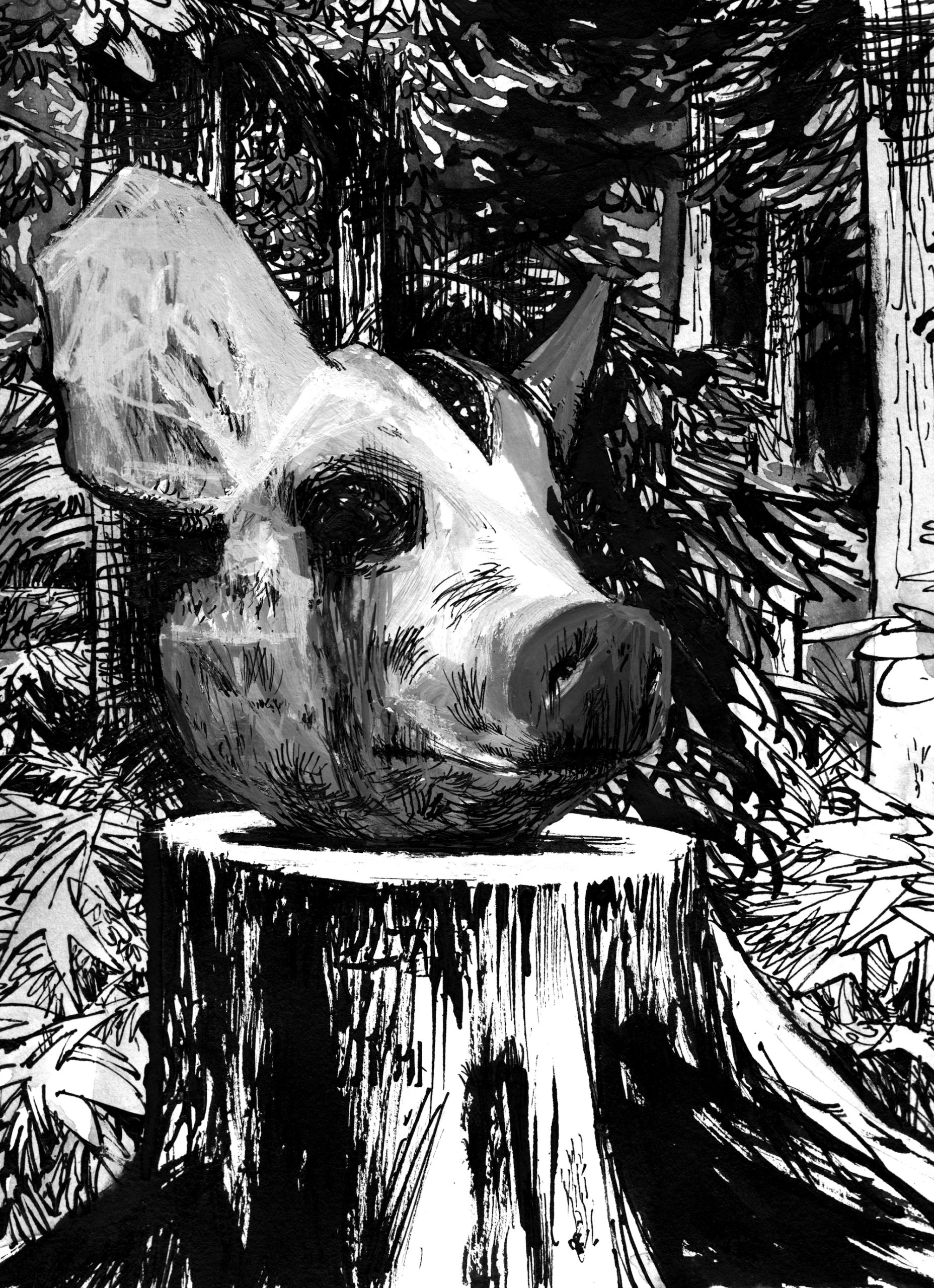

“Where’s her head?” Ed said.

Spitz pointed.

It was set on the rotted stump of a beech tree, a few yards in back of them. Facing its own corpse. Thick tongue lolling out and turning black. The eyes tattered holes.

“Jesus wept,” Ed said.

“So did Alma. She loved this pig.”

“Alma saw this?”

“She found it. Come out here to gather kindling early this morning. Ran back to the house a-hollering. Thought she’s snake-bit the way she took on.”

Ed gave a grunt.

“Inside the head,” Spitz said, “it’s scraped clean like a porridge bowl.”

With a white handkerchief from his pocket, Ed tilted the head back by one of its leathery ears, but the ear slipped from his fingers and the head tumbled wetly from the stump and rolled in the leaves. He squatted, looked up into the neck. “You hear or see anything?”

“Howling. Last night. Elmer heard it, too.”

“Like a wolf?”

“Like a man.”

Ed said, “Like a logger?”

“Could be.”

“They been here almost a month, Jim, ain’t caused any trouble.”

“Took ’em that month to get within half a mile of my property. This is a warning, clear as day, Ed.” Spitz pointed at the unborn pigs strewn on the rock. “They mean to do me and my family harm. Clear as day.”

Ed folded the handkerchief and covered his mouth with it and hunkered down by the carcass. Ran his finger over six purple slashes on the haunch. Each one long and deep and ragged. Another set, on the ridge of the hog’s back. “Ain’t nothing clear here, Jim.”

Spitz craned over Ed’s shoulder. “What you make of them marks? Some kind of saw blade?”

“Can’t say for sure.”

“You can’t say.”

Ed met the farmer’s eyes. Stared hard. “I can’t. Say.”

Spitz bit his words and swallowed them.

Ed followed what would have been the pig’s eyeline from the stump to the slab, where black flies lit and crawled. He wanted her to see ’em, he thought. Wanted her to see her babies.

Overhead, buzzards circled black against a tombstone sky.

Ed wondered, briefly, what old Lesser had done with the pig’s brains.

![]()

Ed had not exchanged words with Lesser Dunn for a long time. A week after Otis Chaney’s funeral, he’d taken the old man one of his wife’s nicer quilts, along with a bundle of food and cornmeal. He’d called out several times but got no answer, so he’d left the provisions on the doorstep of the cave. Promised the old man he’d carry on, keep selling his liquor. And he had, for a while. Until a better offer came along from the company. Until the day a farmer shook his hand and said he ort to run for sheriff. Still, Ed had kept on trudging up the mountain each month for the liquor, always finding a crate of jars on the rock, always leaving in its place a crate of meal and food. A bushel of peas, a mess of his own fresh corn. And cash out of his own pocket, too, what he estimated each batch was worth. Some of the shine he drank himself, but most of it he poured out in a pit behind his work shed, where nothing green grew anymore. Inside, the shed was heaped with empty jars.

Now, as Ed made his way up onto the Bar, horse pinioned far below, rifle in hand, he saw sign of the old man’s coming and going: broken saplings he’d cut to cover a new still, droplets of cornmeal along the damp outcropping. Ed hesitated at the cave, though he knew Lesser was up in the woods above it, cooking, for out of the earthy woods a breeze brought the tingling smell of burning hickory. For a moment, he stood at the edge of the Bar. Looked down upon the valley. A mile, maybe two, eastward, the logging outfit advanced. A wide swath of primeval forest now made into stumps and mud. He wanted it to be them. Wanted to bring down trouble on their heads, to step into his father’s old store and ask to see the boss. He wanted it for himself, for Jim Spitz, for all who lived in the shadow of that rock.

But he knew better.

He found Lesser in a grove of spruces. The by-then ancient shiner was bent in his soot-stained overalls and humped over a fifty-gallon wooden barrel. He stood stirring uncooked cornmeal into a stew of freshly cooked mash. He stirred with a long wooden stick. A stone’s throw away, atop a furnace built out of rock and red clay, a dented copper still smoked and bubbled. Lesser stopped stirring and stared at Ed, blinking. He looked at the Winchester in Ed’s hand, its barrel tilted skyward.

“Lesser,” Ed said.

Out of the mash Lesser pulled the dripping mash stick—a shovel handle with six long, rusty nails driven through one end. He stood it against a spruce tree.

Ed’s eyes followed it.

In a voice that sounded like a rusty hinge that had not moved in years, Lesser said: “It ain’t ready.”

Ed said, “That’s not why I’m here.”

Lesser hunkered down at the base of a tree and squinted at nothing. He plucked at the damp morning ground with his fingers. His clothes hung off him like loose skin.

“Farmer in the holler lost a pig last night,” Ed said. Staring, yet, at the mash stick where it leaned against the spruce tree. Six long nails. “She was pregnant. You know anything about it?”

Lesser reached into the throat of his dirty shirt and drew out something that Ed, in all the years he’d known the moonshiner, had never seen before: a bullet, tied to a bit of string that was knotted behind his neck. The old man’s limbs were long, his elbows sharp. He turned the bullet in his knobby fingers and met Ed’s gaze through a haze of woodsmoke, his eyes sharp and clear and green. He nodded once, slowly, and there was the seed of something terrible in those eyes, Ed thought. A flicker of twin flames in a corridor of blackest night.

Gooseflesh prickled over the sheriff’s arms.

Lesser looked off, and his eyes seemed to dim, to fade.

Ed said, “Hate to ask it, Les, but I need you to come down with me. Into town.”

Lesser tucked the bullet back into his shirt, into a nest of wiry white hair. “Not now.”

Something in the old man’s voice—something certain, something cold—made Ed’s hand tighten around the Winchester. The barrel tilted down from the sky, toward Lesser. Then dipped on, toward the ground, as Ed took a deep breath and calmed himself. He scratched the base of his neck. “I won’t lock you up, if I don’t need to. That’s the best I can promise.”

Lesser stayed hunkered for a few seconds longer. “I trusted your daddy,” he said. He hawked a wad of phlegm into the leaves. “Reckon I can trust you.”

“Sure you can,” Ed said.

So, after the fire was kicked out and the barrels all sealed, the two men walked side by side down the mountain, picking a path over the mossy rocks and rotting logs, Ed stumbling once or twice, the old shiner as sure-footed as a goat.

![]()

An hour before sundown, Ed stood on the jailhouse steps, smoking a clumsily rolled cigarette and missing his wife, whose light touch had always made a firm smoke. How they’d laughed, Ed the only man in the county, Vera reckoned, whose wife rolled his cigarettes for him. Directly, the loggers came and clambered out of their wagons and into Otis Chaney’s old store across the tracks. The sign that hung over the porch now read “Baxter Company Store.” His father’s name had long been whitewashed out. Some of the men were young and loud and whooped and drank from pocket flasks. They fell about one another and held one another up. They seemed to Ed like airy spirits roused from the woods, whiskey-lit and careening nowhere. He finished his cigarette and went inside.

Lesser Dunn sat on a cot in the back cell, elbows on his knees, head of white hair hung between them. Ed’s deputy, Ronald Biggs, had brought a tin plate of steak and potatoes over from Elsie’s before his shift ended, but the food sat untouched on the straw-tick mattress. The cell door was open at Lesser’s request.

Danny Miller was on night duty that week. When Ed walked in, the kid dropped his feet from the desk and stuffed his Western magazine under him where he sat.

“At ease, son.” Ed smiled at the deputy. He carried a wooden footstool into Lesser’s cell and sat on it, trying hard in such cramped quarters not to breathe the old man’s stink of woodsmoke and unwashed skin. The bullet dangled on its cord, out of Lesser’s shirt.

“You under one of your spells last night?” Ed asked.

The old man stared at the rough stone floor.

“If’n you weren’t, what was you doing up there?”

“. . . New still.”

“Up behind Jim Spitz’s property? What the hell for?”

“He got a branch runs off his place. Water’s real clear.”

“And the sow?”

The old shiner’s eyes flicked left and right, as if searching for the why, the how, in the corners of his cell. “Reckon it was rooting in my mash. You know how a pig loves mash.”

“It was in its pen, Lesser. It was drug up that hill. You do that?”

Lesser shrugged.

“I want to help you. Do you believe that?”

“You a honest man.” Lesser looked up, straight into Ed’s eyes.

Ed felt a weird prickle, on the back of his neck: He knows. He knows you empty them jars. He knows you pity him. And it wrecks him, to be pitied. It wrecks us all.

“Why don’t you stay here tonight, Lesser. Where you and Jim Spitz’s livestock will all be safe. What do you say?”

The shiner’s eyes flicked away then, to the open cell door. “Can’t,” he said.

“Seems it’s a hair better than an old damp cave.”

“Can’t do no jail. I told you.”

“We won’t even lock the door, will we, Danny?” Ed called up to the desk.

“No, sir,” the boy called back down the hall.

Here, Lesser’s voice dropped. His hands roamed back and forth over one another, whispering, as was he. “She told me to do it and I did it, Sheriff. But I felt bad after. I wanted her to see her little ones, but it was too terrible a thing to see. I took her eyes so’s she wouldn’t have to look. The other one, the one up there, she didn’t like it. She said I’s weak. And now she’s telling me: I can’t be here tonight.”

For the second time that day, Ed felt gooseflesh burst over his arms. “The other one up where?”

“Her,” Lesser said. He cut his eyes up high, at the narrow window, through the iron bars, beyond which the sky was purpling into twilight and the moon hung full and round like a piece of crosscut bone.

An uneasy feeling crawled around inside Ed. He thought of the day of Vera’s funeral, when he’d gone up the mountain in the rain, same black suit he’d worn to his father’s grave now drenched, hat brim dripping cold water. How he’d stood outside the maw of the cave and called for Lesser, begged him to come out, but there was only the sound of his own voice hollering back down the long throat of the rock. That, and the rain, a curtain of silver shimmering over the mouth of the cave, like a veil separating Ed Chaney from the last great mystery. There, he’d sat in the rain and wept, high above a world forever changed, a wilderness made remote.

“Lesser,” Ed said. “I’m locking you up tonight. To keep you safe. From yourself. Do you understand?”

The old shiner never moved as Ed crossed the floor of the cell, carrying the wooden stool with him. He pulled the heavy iron door shut. He told Lesser that Deputy Danny would see he got breakfast in the morning. Then he turned the key and the lock clicked, and as he turned away, he heard Lesser say, “May not be a chance later, so I’ll say it now.”

“What’s that?”

“Your daddy’s was the only kindness I ever knew. I’m sorry.”

“Sorry for what?”

“For him. For your wife. For whatever happens tonight.”

Ed stood watching him. He told himself he was doing the right thing. He had been telling himself this, he thought, for a very long time.

Lesser stuck a finger in his mouth and dug at something between his teeth with his nail. He looked at his tray of meat and potatoes, set it gently on the floor, and lay back on his side. He tucked his knees up to his chest and lay on his cot with his eyes open, staring up at the narrow window of his cell. At the moon.

![]()

Ed Chaney slept fitfully that evening, troubled by dreams of his father and his dead wife and the dark cave at the top of Black Arrow Rock. He dreamed he was eating something red with his fingers out of a human skull. He sat at a fire and across the fire was his father, and beside his father was Vera. And when he passed the skull to his father, Otis Chaney looked into the bowl and stared back at his son as if he did not know him, and that’s when a pounding on the front door jerked Ed awake. He kicked off the sweat-soaked covers and strode in his long johns into the vestibule. For a reason he couldn’t immediately figure, he reached for his Winchester where it leaned beside the door. He’d never done this before, and he’d answered many a late-night call at his porch. The dreams, he told himself. “Who is it?”

“It’s Danny, sir,” came an urgent voice.

Ed set the gun aside. He cracked the door. “Danny, what’s—”

The door opened on the lean, boyish face, pale and frantic in the moonlight, his short red hair plastered to his forehead. His horse stood snorting in the yard. “Sheriff, you gotta come. I’m all alone down there and—”

“What the hell are you up to, abandoning your post?”

“The old man’s acting plum weird, Ed, and I don’t think I should be the one—”

“What’s wrong? Is he sick? He has fits, sometimes.”

“I don’t know. I don’t think it’s like that.”

Ed took a breath. “Fine. Ride out to Ronald’s. Bring him back. I want you both there in a quarter hour.”

Danny turned and ran for his horse.

Ed shut the door and went to find his pants.

![]()

He’d just drawn up to the hitching post outside the jailhouse when an inhuman cry froze Ed in his saddle. His horse danced back, into the street. The sound shot out from the narrow alley between the jail and the post office, from Lesser Dunn’s narrow cell window.

The moon above was huge and yellow.

Ed dismounted, calmed the horse, and hitched it.

Inside, the shiner was on all fours in his cell, scuttling back and forth across the concrete floor. His mouth drew down in a rictus of pain. He made snarling, trapped sounds. Mewled. His cot was upset, mattress and blankets flung across the bricks.

Ed only stood and stared.

He almost hollered when, behind him, Danny said, “It started about nine. Ronald’s on his way.”

Lesser slowed his pacing and began to whine up at the window. He reached up toward the bars with crooked, gnarled fingers. His hands shook.

“He say anything?” Ed asked.

Danny scratched the side of his nose. “Yeah. Called me a shit-eating pig fucker.”

A howl, like a rupture of the spirit, deep inside the old man’s chest, and then he collapsed into a corner and began to tug at the neck of his shirt and grunt and heave. His whole body arching as if in the throes of some galvanic current. He began to tear at his overalls and shirt. He threw them into a corner of the cell and rose upright from hands and knees, then ripped away his undershirt and stood half clad, bullet bouncing against his chest. He raked his fingers down his face, even as a bright yellow circle began to spread on the crotch of his long underwear.

“Damn, Ed,” Danny said. “He’s just pissing.”

Raising his big hands and skinny arms above his head and arching his crooked back, the old shiner drew in a deep breath and let out a gut-wrenching scream. He continued to scream, over and over, even as he tore at the cotton of his soiled undergarments, until finally he stood naked before them, arms thrust heavenward, as if caught up in some horrible state of religious ecstasy.

Danny backed away, toward his desk. He wore, Ed noticed, his Colt revolver.

Ed himself held his Winchester. Held it so hard his knuckles were white.

The old man’s cries ceased suddenly, the ensuing silence tomblike.

It was then that Deputy Ronald Biggs, who’d been standing waxen-faced in the open jailhouse door, made his presence known by saying: “God a’mighty, fellows, would you look at his pecker.”

Surprised, Ed and Danny turned to Biggs, who pointed.

Indeed, they looked and saw that Lesser, who was sniffing the air and grunting now, had an incredible erection. His liver-spotted penis jutted from its nest of pubic hair like an angry rhinoceros horn. “COW HUMPING TITTIES!” the shiner cried, dropping to all fours.

Ronald Biggs threw back his head and laughed.

“God,” Danny said.

“TEAR YER SHITTIN HEADS OFF AND COOK YER BRAINS, YOU SONS A BITCHES!”

Suddenly, Ed remembered his dream, his father holding a skull by firelight.

Lesser’s forehead struck the iron bars of his cell as he threw himself against them. He licked at the blood as it coursed over his mouth. Again, he hurled himself at the bars.

“Stop that, Lesser,” Ed said. His voice trembled.

Lesser grinned, backed away, gathered his legs beneath him, and sprang again. And again.

“We’ve got to stop this,” Danny said.

“Let him knock himself out,” Biggs said.

“He’ll kill himself trying,” Ed said. He threw his Winchester across the desk and snatched a heavy ring of iron keys from a hook on the wall. “Get me that rope from the cabinet, Ronald.”

When he saw Ed coming with the rope and keys, Lesser scurried to a far corner of the cell, crouched down, and pressed his weight on his knuckles. He hissed: “That’s right, ballsuckers,” then gave out a higher-pitched howl, one that was pure animal.

It made Ed falter, key in the lock. “Danny, you cover us now.”

Danny drew his sidearm.

“He’s just an old man, Ed,” Biggs said.

“Not right now he’s not. Right now he’s something else.”

The key turned, the lock clicked, and the door popped open a fraction of an inch. Ed swung it wide and the two men entered. In the second that Biggs was locking the door behind them, Lesser sprang, quick and low, to the deputy’s side. Ed held the rope in both hands, tried to wrap it around the old man, who instead wrapped himself around Ed’s leg and bit down. Ed cried out, trying to get the rope over Lesser’s shoulders, even as Biggs grabbed the shiner around the waist, trying to pry him from Ed’s leg. Lesser let go and he and the deputy went tumbling, and as they went, Ed heard that gentle, easy sound of a pistol leaving its well-oiled holster and had time enough to blink and see Ronald Biggs’s sidearm in Lesser’s big-knuckled hands before the old man put the barrel to the deputy’s temple and squeezed the trigger.

The top of Ronald Biggs’s head blew apart.

The explosion drum-bursting.

The next bullet caught Ed high in the shoulder, hurled him back against the bars.

And now Lesser Dunn was up and leaping at the door and Danny was firing at him, but the old man was moving too fast. Danny’s bullet sparked the iron and ricocheted into the brick, where it remained until the old jailhouse was torn down in 1933. The pistol bucked in Lesser’s hands and Danny skipped backward onto the desk, scattering adventure magazines. Ed’s Winchester rifle clattered to the floor. The sheriff himself slumped against the cell bars, shoulder on fire, as above him Lesser snarled, twisted the key where it still hung in the lock, and threw open the door of his cage.

He leapt on Deputy Danny, still sprawled on the desk.

Lesser howled.

Danny screamed.

Ed scrabbled across the floor to his rifle. He seized Lesser from behind and hauled him off his deputy, then threw him to the floor.

Flat on his back, Lesser brought up Biggs’s pistol. Spittle flew and he snarled: “SHITHOLE!”

Ed shot him in the chest. The Winchester bucked and blasted Lesser Dunn’s life onto the stone floor. He was dead before the deputy’s pistol had slipped from his hand.

It was said, by some, that Lesser did, in fact, shrink before the sheriff’s eyes, diminished from the wild thing he had become. Just an old man again, that strange bullet yet around his neck. Naked, dead, nothing more.

Ed knelt beside him, heart a runaway carriage in his chest. He followed Lesser’s glassy gaze heavenward to the jail’s beadboard ceiling, the wood there warped and water stained. What do you see? he wanted to ask. What do you see?

Danny moaned. The boy’s left eye was gouged into its socket. Blood pooled there, trickling down the deputy’s cheek.

Ed got moving, ran all the way to the doctor’s house.

![]()

In the days that followed, with his right shoulder and arm in a sling, Ed Chaney went up onto Black Arrow Rock with an axe, a gallon of kerosene, and a box of matches and destroyed Lesser Dunn’s still. He poured out barrels of fermenting mash and hacked them up as best he could, burned them, then broke apart the rock furnaces and copper cookers. He smashed all the jars of liquor he found—all but two—and buried the shards.

He went into the cave and looked around by the light of a kerosene lantern. The rock rose up sharply on either side and glittered with minerals and damp. Quickly, the ceiling became too low to stand upright, until finally it opened onto a narrow chamber, the floor of which was littered with the pale, gnawed bones of tiny animals. A few of these were bigger, one the length of a man’s shin. Scattered among them, a pack of nudie playing cards. Far overhead, an oculus of stone through which a fattening moon shone out of the bright blue sky. Finally, in the farthest corner of this den, Ed Chaney found his dead wife’s quilt, worn and wet, but folded neatly on a slab of rock.

He took the quilt and wrapped the last two jars of shine in it and carried them off the Bar. Then he rode out to the doc’s house near the sawmill, where he found Danny Miller sitting on the porch, sporting a black eye patch and a splinted leg. They sat together and drank the moonshine until nothing made sense and everything was clear.

A few months later, we weren’t all that surprised when Ed Chaney left the office of sheriff. The woods all around were gone by then, the Baxter Company had moved on, and his father’s old store was empty again. Some folks said Ed went south, down to where the trees were sharp and spiny and the air was warmer. Others said he went west and crossed the Mississippi, took a job with the US Marshals Service in Fort Smith, Arkansas. Others said he went north, into the Smokies, where he married a half-Cherokee woman in the business of making pottery. It’s said, on the night they wed, after all the lights were out and husband and wife had made love in the dark, the bride woke to find the groom’s side of the bed cold and empty. So she slipped from the covers and walked barefoot through the cabin until she saw her husband through the screen door, silhouetted on the porch at the rail, naked. She stepped outside and pressed up against him, ran one hand over a pale white scar—a camellia bud—on his shoulder.

“What, old man,” it’s said she asked, “do you see, out here in the dark?”

And Ed Chaney, the people who remember him say, pointed to the full moon in the sky, touched the bullet that hung around his neck, and answered: “Her.” ![]()

Andy Davidson’s most recent novel, The Boatman’s Daughter, was listed among NPR’s Best Books of 2020. His debut novel, In the Valley of the Sun, was a 2017 Bram Stoker Award nominee. Born and raised in Arkansas, he makes his home in Georgia with his wife and a bunch of cats.

Illustration: Matt Rota