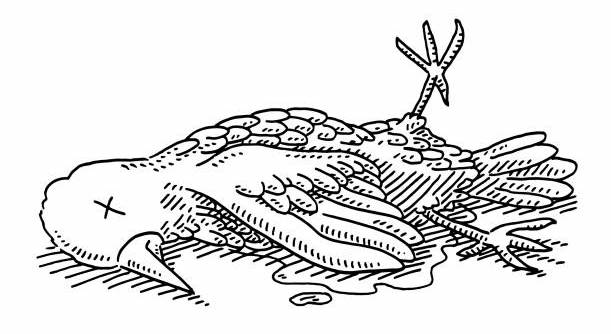

The birds began falling dead, tumbling earthward in great clouds. Millions of them. They fell and fell, and we became consumed with the proper naming of the thing, as if affixing the right name to it might save us. Might stop what was happening.

Large pale heads appeared on television, their foreheads sweat-damp. They regaled us with terminology and facts. We took a grand comfort in it; their words were serious and grave. The fields and streets lay clotted with dead birds even as they continued to fall in inked swaths from the sky, as they tumbled like stones into the chokepoints of chimneys. As they starred windshields blue with impact and a black smear of feathers. The large pale heads gathered on-screen and their words were like incantations against the dark: Zoonoses. Spillover. Cross-contamination. If we named it, we believed, it might become less fearsome. Our torch against the night.

So we became obsessed with the names of things even as the naming did little else. We called on our leaders to take action and some of them issued statements of concern, statements that showed how troubled they were, while others were maddeningly silent—waiting, perhaps, to see what would happen next.

It was an aching, crystalline winter afternoon and you peered up at the sky and said, “Maybe we can catch one before it hits the ground. And then we can rescue it. And feed it, and make it a little birdhouse to live in.”

We were standing out on the deck when you said this, your eyes turned up to the white, featureless sky. You had always been a watchful child. Your caution a thing born of necessity, I imagined, given the nature of your life. That morning we could hear nearby trees crack in the silence, their limbs grown too heavy with ice. I was grateful for the cold—the previous summer had scoured the nation with wildfires; smoke had grown toxic and heavy in the air, casting our days with a strange and noxious pall, days where we could not step outside.

But I recognized in the smoke, and later the falling birds, that the world of my boyhood was dead. I was an old man who could no longer expect the world to behave as it should.

On the deck that afternoon, your breath danced from your mouth in shuddering clouds. Your mittened hand was clasped in mine. I stared out at the backyard, shapes out there softened under the snow: a lawn chair, your grandmother’s wheelbarrow. It would be lunch soon, and Helen would make us all sandwiches and heat up cans of soup and then the three of us would sit at the kitchen table and play Go Fish, Old Maid, Pass the Pigs, until your mother called us. We would try not to flinch if a bird hit the roof, or plummeted, a dark bullet, into the snow before the window. It had happened before, and every time it reached between my ribs and squeezed there at the tender meat of my heart.

“Honey,” I said to you that afternoon, and gave your hand a squeeze. “I think they die when they’re flying. Up in the air. I don’t think they can use their wings anymore, and that’s why they fall.”

I watched you try to understand this. A snowflake fell on your eyelash and began melting, jeweled there, slowly vanishing against the heat and blood of your living. I felt a stutter of fear of what the future might hold for you, for the rest of your unbroken life. The fear was like someone pulling a thread taut. It was not a new feeling in me.

Winter broke loosely, ugly, a drunk spilling change on the floor. Spring brought thawing and floods, tornadoes, states suddenly waist-deep in mud-water. We watched the news, the three of us, saw streets of small towns grow brachial with dark floodwaters, water spread out like the veins of some opened heart. The now-common sight of people moored on the roofs of their homes.

Soon you began having nightmares after watching the news, nightmares in which Helen and I tried to save you from drowning and could not, couldn’t pull you up from those dark waters.

I blamed myself. Who else was there? Your mother was my child; you were the blood of my blood. We should have known better than to let you watch the world’s unraveling. You would cry out at night, and when I came to your room, you gripped my neck, small-limbed and sweaty and weeping, your pajamas soaked in urine. This small weeping child, clutching at me, afraid to let go. You wanted your mother, pined for her. Those nights, I felt a flash of self-pity, quick as a knife-twist: I was an old man who had already raised his child. I shouldn’t have to be the one doing this.

“Your mother is doing the best she can,” I wanted to say.

“She loves you,” I wanted to say.

But I said nothing like it, held you in silence. We lived in a time, after all, where the naming of the thing counted for nothing.

Spring rains incessant, spring rains torrential. Even on our hill, our basement walls wept water. Your feet sloughed dead skin from playing outside in your boots so much. The birds, so said the pale heads, were dying in smaller and smaller numbers; they were mostly gone now. There would be, they said, devastating repercussions from this, in an ecological sense, and Helen wisely changed the channel when you came into the room now. Your mother lost phone privileges for a while—a fight with another inmate—and Helen and I took turns naming the things your mother loved about you, the things we loved about you. Your long toes. The freckles dusting your cheeks. The way you said “Excuse me?” before you asked a serious question. How you lifted your chin when you laughed, as if informing the world of your joy. Your tenderness, that ceaseless caution. Your kindness toward a world that had been profoundly unkind to you. Your endless, endless resiliency.

Here then, there was no shortage of things to name.

You had a birthday and we invited your schoolmates, and for an afternoon our old creaking house was filled again with the sounds of laughter and yelling and children’s feet thundering up and down the stairs. Parents closed their umbrellas and carefully avoided questions about why a six-year-old—no, seven now!—was living with her grandparents.

Helen’s cake brimmed with candles and the children jostled for a spot next to you, and as you made a wish, your lips silently moving, there came the sound of a window breaking upstairs—the adults exchanged glances—but you and your friends were too enrapt with the cake to notice. You blew out the candles and everyone clapped and I trod stealthily up the stairs, as if to surprise the tiny body splayed out beneath the skylight, its wings fanned on the carpet.

The rain, assured the large pale heads, would be good for the snowpack, even as rivers flooded their banks, as towns became submerged.

Next went the dogs.

Black clouds that dissipated in an eyeblink, clouds where a dog had been, a pet, clouds that left a fine wash of grit where a living thing had been only moments before. Perhaps a chip of bone left, a flinty shard of tooth among the black smear. So many gone, in a span of days! Think of how many millions of dogs there were in the world! We watched scenes of it on television, on Helen’s laptop, our mouths knit in tight, bloodless lines. The way the natural world seemed to be joyously, darkly veering off its given path.

There were reports then. Of unrest, of riots. Guardsmen called in to flank city streets, police firing their guns into crowds of frightened people. Godly ones screaming on street corners.

We shut the curtains and closed the laptop and played Go Fish, Old Maid, Pass the Pigs.

The dogs continued to disappear in their curls of char, their wash of black sand.

I realized then that I must consider that a person can grow accustomed to anything. The world felt as if it had become some strange and malevolent dream. Helen spent an afternoon on the computer—she was always better than me at navigating technology—and came back to the kitchen table looking dazed and frightened.

“There are all kinds of opinions about things,” she said, “but no one knows. Everyone thinks it’s a conspiracy—”

“Of course they do,” I snorted, grateful for the contempt I could muster. Luxuriating in its safety, its distance.

“—but everyone thinks it’s a different conspiracy. Russia, the government. PETA!” Helen laughed drily, pressed her knuckles against her mouth. The rain kept falling. The street was empty, silent. We had cultivated this—this quiet street, this house on a hill, food, clean carpets, ceilings that kept the water out—through decades of sacrifice and hard work, and there seemed no shortage of things conspiring to encroach upon it. First there was your mother (forgive me, it’s true) and her endless hellraising, her drugs and drinking and willingness to place herself in the indebtedness of terrible men. Her willingness to call that love. How she raised you as an afterthought at times, how that killed Helen a little bit, the sometimes offhanded way your mother loved you. Perhaps this isn’t kind of me. The caseworker urged us to view your mother’s trajectory with compassion, that she was locked in the arms of her addiction, and I wanted to tell her that we knew your mother. We’d raised her, after all. We’d known her as a little girl, willful and stubborn and afraid of so many things, so angry, and we’d watched her grow, saw her veer willfully toward paths other than those we’d wished—demanded—for her. So first your mother and her arrest and how you’d come into our lives. We retired years ago, and hadn’t been expecting this. We had cultivated a life and you threw a monkey wrench in it. Helen wanted to see Rome, walk the dusty streets of Pompeii with a camera, before her sciatica got too bad. She wanted to order wine in her terrible French at some busy Paris café. These, I felt, were not unreasonable dreams. We had saved, been frugal. We were selfish enough to think that we deserved such things. But what could we say? To the DHS worker, to your mother? To you? Sorry, dear, but we were planning our vacation?

Sorry, dear, but we are tired?

This is how love works—it snares you in spite of your intentions. If it weren’t for Helen and me, where would you go? Where would you land, in a world where birds plummet from the heavens and animals turn to smoke? Love is an anchor, dear heart. Love is a debt endlessly paid, repeatedly negotiated.

It’s impossible not to blame myself in a situation like this. I felt that I had failed your mother in some intrinsic way, though I never told Helen this. That she had come to rely on weak-chinned, hurtful, violent men, men that used her—what did that say about me, as a father? The caseworker talked about addiction as a disease and Helen and I nodded in sympathy, but I didn’t believe it. I knew that I had failed her. I had not been strong enough, loving enough. Disciplined or flexible enough. Some combination of things.

And now: we took care of you and the world filled slowly with smoke and floodwater and death. And then the rest of the animals began perishing in the strangest ways, the hands of some terrible clock moving faster along.

Tigers—rare enough in the world—turned to glass, frozen and blue.

Sharks hardened to ceramics and tumbled spinning into dark and unseen waters. Perhaps shattering on the ocean floor, perhaps coming to rest gently in the silt like a shopkeeper laying a precious gift in tissue.

The brains of gorillas turned to shards of crystal; the animals fell in a collection of limbs, brainpans shattered and filled with treasure.

Ants became grains of sand.

And then: the buds of fruit trees turned to stone, stones that clattered to the ground.

Insects disappeared in small puffs of frenzied air, minute cyclones.

The world was quickening, leaning, wounded.

Summer. Riots. No electricity. Money had become valueless. The supply chain had broken down. Stores burned to the ground. Libraries robbed of their paper. The roofs of churches bristling with guns, their floors slicked in blood.

A dead man lay face down in the road at the bottom of our hill, grown huge with gasses.

We had taken as many precautions as possible, stockpiling and whatnot, but hunger still carved the fat from us. Cabinets bare, I walked the house hollow-eyed, a revenant. Clutching my service pistol, a thing untouched for forty years before this.

Your head, dear, was like a skull with the skin wound tight. We were all so hungry.

Helen fed you her rations—vegetable broth, a knuckle-sized potato—and then, with a look both baleful and shocked at my reluctance, bade me to give you mine as well.

And I did. And you ate. And love was a debt navigated and incurred and paid a million times a day.

Then, that summer day, we stood out on the deck, you and I. Hot outside, hot and still. Helen was in bed upstairs.

Sand riffled in eddies down the hill, sand that claimed the dead man now. No birds, though, to pick at the flesh of him.

You and I, we stood and stared at the backyard. A hot wind blew across the yellow grass. There was the lawn chair. The overturned wheelbarrow. Somewhere someone rang a bell again and again. I remembered the way the snowflake had fallen on your eyelash and melted there, back when it was only the birds that were dying. Back when we believed we were impervious, that nothing terrible could truly happen to us. That this collapse was something separate from us, something to marvel at.

I held your hand and I felt something fierce and brutal within me, some animism that raged against the walls of the world. A rage that I had again failed at protecting someone, that the world had made me small again.

And then I felt a lightness in my hand. I looked down and saw that I cupped a handful of vapor. Mist. Mist that held your shape, and then you blew away on that heated wind, an outline of you on the worn planks of the deck.

You were gone.

You were gone, and I felt fear, and a yawning chasm, and a hidden, animal relief.

I saw the water droplets on the deck—the shape of you—disappear in seconds beneath the sun.

I called your name. Timidly at first.

Then louder, screaming it, needing the ache and rasp of your name in my throat. Finding at last a territory of belonging in your vanishing. Finding a sick, hateful succor in the fact that I had failed to save you. I screamed again, a pure animal sound. Something in my throat threatened to tear, and I wanted that.

I screamed and screamed. I would do this, I decided, until the diminished world began forging itself back together again. ![]()

Keith Rosson is the author of the novels Smoke City, Road Seven, and The Mercy of the Tide, as well as the story collection Folk Songs for Trauma Surgeons. His short stories have appeared in PANK, Cream City Review, Outlook Springs, Phantom Drift, and others. He is also a legally blind illustrator and graphic designer whose clients include Green Day, Against Me!, and Warner Bros.