Time wore on up there in Alaska, while I—barely half a duo by that point, no longer a Brother to anyone—watched the Fever spread. Though it had eroded both its origins and its nature, to the point where I could say neither how it had begun nor what it had become, I couldn’t fail to perceive its presence in the bleak fishing town I’d washed up in, along with the crimes I’d committed.

I’d done what I’d done, down in California, and there was no denying it, nor even slowing the rate at which it was bound to continue up here, not so much catching up with me as emerging from whatever now passed for my being, as if my entire northward journey had been for no purpose other than to birth the Fever in its mature form. Bodies turned up dead, sacrificed to wax Squimbop statues that would never come alive no matter how hard I, or the dozens of others like me, tried. We did all we could, and more than we should have, but wax remained wax and flesh remained flesh, whether living or not, and we remained alone, sealed off from ourselves and one another, nodding remotely when the ding of the diner door was louder than expected, keeping our eyes on our eggs and burnt toast when it wasn’t. Mouth full of the toast that none of us could keep from burning, as if the heat from the toaster were impossible to resist, I’d drink coffee with more sugar than it could absorb, enough to sicken me, trying whatever I could think of to kindle a buzz inside my khaki coat up there in the pitch dark, under stars that seemed deployed to menace me in particular, portending a strange new chapter that was ready to begin and yet, still, wouldn’t.

There was no question of bringing the Fever to a halt, nor even any serious means of trying. Any officer saddled with the task quickly succumbed to it, as the Fever spread quickest among those who evinced even a modest intention of curtailing its trajectory and living complete unto themselves rather than as half of a sundered Squimbop duo. One officer after another—Pinkertons or Pinkerton impersonators, sent up from Portland and Seattle, or self-deputized, in the grips of a primitive vendetta that amounted to no more than another symptom of the same condition—succumbed as that first, black winter in Alaska gave way to the next and the next and the next, the distinction between them purely philosophical, or even less than that—an idiot’s notion of philosophy cribbed from the kind of Borscht Belt routine that, in another life, part of me still believed my Brother and I used to perform, to rapturous, if ghostly, applause in the function rooms of colossal mountain hotels, so deep in the Catskills that, as I might’ve quipped back then, my accent that of a Yiddish-speaking child who’d learned English at public school in Canarsie, time nearly forgot to forget them.

As the winters passed, more and more of the town’s dark storefronts, whether they’d once been leather goods outlets or antique malls or saloons, grew marquees until, it seemed, every space that could possibly become a cinema had become one. Whether this represented a distortion of the town or the emergence of its true form was another question that the idiot philosopher I’d once played, while my Brother played my endearingly puckish, unteachable pupil, enjoyed pretending to consider while hopping from leg to leg in the freezing dusk before the show began.

In those very deepest of the Alaskan days, which in retrospect I miss almost as much as the Borscht Belt days buried under so many layers beneath them, and yet, along another axis, cloaked in the very same shadow and thus nearly equivalent, I hurried from one makeshift cinema to another to another, many with walls that didn’t quite meet and roofs made of aluminum and fiberglass that rode up in the vicious wind, my patched-together khaki coat pulled tight over three sweaters. If I could get the timing right, I’d catch three or four runs of Brothers Squimbop Classic Era revival shorts in three or four cinemas along the only street of that exhausted, murder-soaked town high up along the coast of nowhere, as close to the top of the world as the living can come without traversing a twilight zone beyond which all events freeze into legend and in that sense cannot occur.

I sat in the dark and watched, over and over again, The Brothers Squimbop in Europe and The Brothers Squimbop in Hollywood, The Brothers Squimbop Burst the Borscht Belt Vol. I and Vol. II, and even rare showings of the nearly snuff-grade Squimbop Fever, probing the snowy footage onscreen—the snow falling outside penetrated the cinema, filling the empty space between me and the screen with soft gray fuzz—for any hint as to the nature of my old face, any clue within the expressions of the actors or documentary subjects that these stories, which I remembered so well, or at least felt that I ought to remember well, were indeed about me, so that I could be certain I had once been elsewhere, and might thus end up elsewhere again.

The films, I insisted, were about me and, of course, my Brother. There were nights when the return of his absence was enough to send me reeling onto the streets before the credits rolled, knife drawn even as the population of eligible victims dwindled toward zero, replenished only by stringy drifters deposited in silence by the Night Bus. On such nights I’d drag them stunned and insensate toward the shed behind the diner where I worked three days a week, just enough to pay for my room out by the gas station and for occasional visits to the glaring white grocery store, on a corner where, even in the daytime, the sky was always black.

Inside the shed, I took no pleasure in going through the Fever’s motions, rote as a nickel-operated roadside attraction, though sometimes, in the necessary heat of the routine, I’d flash back to an earlier go-around, farther down the coast, in Oregon maybe, and, as the hot blood pooled around the feet of that shed’s wax Squimbop, melted and refrozen so many times it looked as muddled as I felt—every shed in town had one, presumably crafted and left there by an earlier Squimbop generation, even more naive than we were in its belief that the Fever could be satisfied through sacrifice—I’d feel a shiver of purpose return, and, for a blessed instant, it would seem as though the insanity I’d long ago consigned myself to wasn’t yet terminal. Perhaps, I’d think, as I locked the shed and dragged the spent body on a hook toward the dump just as the Night Bus pulled back into town, I’m no closer to this story’s ultimate end than I am to its long-forgotten beginning. Perhaps I’m still a sane, strapping dweller of an expansive and even nutritive middle, with much excitement and a little satisfaction still to come, my time outside the clarifying bond of a Squimbop Duo only an interregnum, soon to be restored, so that these long, strange days in the dark will seem to have been no more than a necessary regrouping between one tour of the Inland Circuit and the next, from the Catskills to Lake Tahoe and back and back again, a thousand times over, unto the eternity that my Brother and I, after all we’ve been through, surely deserve.

When I went to sleep on nights like this, improbably warmed despite the unremitting cold outside, I’d sink into my thin mattress and begin to rock, as if I were already at sea, floating as fast as the waves would allow back out into the world, never to revisit this lonely phase again. I’d lie there watching the terror of my singularity recede as a new shore of restored Brotherhood pulled into view. In other versions of the dream, as fluorescent light from the grocery store across the street filtered into my room, both of our heads would rise from the ocean’s depths, titanic and mossy, mountainous, volcanic, twin Atlantises named Jim and Joe, resurrected from the innermost vault of the world’s founding blueprints. Then, if I couldn’t keep from sleepwalking, I’d find myself back in the cinemas, which seemed never to close—or else to open whenever I turned up—watching Squimbop footage at three and four in the morning, when it appeared raw and unedited, as the northern lights danced in the rocky crags to the east, and the frozen Pacific split the docks in that town’s narrow passable stretch of harbor.

This footage likewise grew increasingly nautical, exchanging the familiar pie-stand and hotel-lobby sagas of the Squimbop Golden Age for new material set upon a colossal turn-of-the-century steamer or, in some instances, a rough but sturdy Norwegian deep-sea fishing vessel, adjacent to but clearly distinct from the ferries my Brother and I rode so many times to and from Europe, back in the Golden Age these films seemed determined to commemorate, as if they’d developed a memory of our circuit while they traced their own, from theater to theater around the continent, before ending up here, at the very end of the line, where no one wanted them back and they were thus free to unspool and drift into dust, hovering in the air that only I was breathing.

I’d breathe this air in and out and in and out until Tommy Bruno, the bald, smiling, tuxedoed usher and concession man who’d been here so long that I could see the cinema going up, board by board, around him where he stood in the snow, ejected me for a between-film cleaning, squeezing my shoulder with a delicacy that indicated he was well aware of my state, having seen many of my forebears grow fragile along similar lines. Still half-awake and fearful of the air outside, I’d then find myself back at the diner, either cooking if it was my day to cook or chewing eggs and burnt rye at the counter if it wasn’t, and then, with a thin paper cup of dangerously sweet coffee in each hand, I’d find myself at the harbor, sitting on a bench, listening to the waves crack and crunch together, watching the horizon for the ship that I was certain would be here soon, emerging out of the static just as it would have if I’d been allowed to remain in the cinema.

Indeed, it was not lost on me that, if I could see myself from afar, the tableau of a fading Squimbop on a bench with two coffees about to freeze would sync up exactly with the last scene from the film I’d watched the night before, and the night before that, and perhaps—nothing, when it came to gaps or eerie continuities, seemed impossible up there in Alaska—every night of my life, slowly developing a naive Squimbop obsession that, I couldn’t help but suspect, had no more to do with me than it did with the billion others who’d happened to see the same footage and latch on to it with the same desperation that, by this point, was probably all that kept us alive.

As I sat there and sipped and waited and watched, feeling myself uneasily housed within an iconic Squimbop Pose, the kind that everyone would’ve recognized years ago, or would come to recognize years from now, if and when the famously scandal-ridden development of the Squimbop Media Center in Cooperstown, New York, was completed, I began to understand, through no force other than what I could sense in the wind, that the supply of stringy drifters would soon run out, and that it would then be time to renounce the Fever, even if I was far from cured, and resign myself to the care of the captain of whatever Ship of Fools finally materialized out of the premonitory murk I could tell it was already sailing through, assuming the pride of place in my imagination that, until now, the Night Bus had occupied.

After all this became clear to me, the run of winters peaked and began to trickle toward spring. The ice in the harbor broke up and ran back into the ocean, and the superabundance of winter cinemas reverted to grain storage and ironworks, until only one remained. It was there that I watched the first half of my final murder, a flickery, groaning scene, the footage much degraded after playing in a hundred towns before this one, in which I scooped up a barely conscious drifter in a slick raincoat, fresh off the Night Bus and huddled on the far side of the otherwise empty auditorium, and marched him down the stairs to the basement restroom, its walls adorned with scuffed maps of the subways of Paris and London, and began to saw mechanically at his throat, back and forth and back and forth, in time to the clattering of the footage overhead, until I could no longer be certain whether I was watching the scene or acting it out, watched by yet more Squimbops in a silent theater—the Real Theater, I thought, home of the Real Squimbops—on the other side of a screen whose existence I could just barely intuit, deeper into a topography that, at times like this, I could feel extending all around me in a precise yet inscrutable design, built as a stage for all that was going to happen.

Admitting this allowed me to likewise admit that I was confused about whether the man I was sawing was a real drifter or a wax statue, and thus whether I was sacrificing him to a sacred Squimbop effigy in hopes of bringing it back to life—thus was the narrative of Squimbop Fever, as best I could recall—or, rather, slaying the last of the innumerable wax idols that had, for far too long, stood between my Brother and me.

I sawed his, or its, head clean off as I deliberated, growing ever more certain that, beyond all that was irresolvable in these questions, some clarity was indeed pulling into harbor; I was indeed making a kind of progress.

When I was finished, I placed the head in the trough of the ceramic urinal, wiped my fingers along the Champs-Élysées, buried the knife in a wastebasket full of ticket stubs, and walked upstairs, picturing myself emerging onto the upper deck of the ship that would sail me to the reunion I was now certain I had earned. As I passed the concession stand for what I considered to be the very last time, Tommy Bruno awoke from a doze, smoothed his bowtie, spread his hands across the warm surface of the glass tank that held the fresh popcorn, and smiled in such a way that made it clear he believed I would soon be back.

![]()

Precisely as I’d foreseen, I emerged abovedeck just as the ship was pulling out of port, icicles forming along the thick coil of rope that held its weed-choked anchor. Whether I surfaced first in the cinema and then proceeded through one last tour of that godforsaken outpost, stopping in my room by the gas station to fill a duffel bag by the light of the grocery store and then at the diner to quit the job that had made possible my stay in that room, taking three limp twenties from the register, or if this sequence was merely implied, seems now, as I watch the Alaskan coastline recede, to be well beside the point.

For the first time since our bleak sojourn in Hollywood, a spirit of newness hangs over me, a sense that the Brothers Squimbop are, at last, soon to be deployed in tandem again. Men clearly in the grips of the same conviction line the edges of the upper deck, keeping their distance, some reclining in hammocks, holding their coats to their sides as the wind shears past, while others lean overboard to watch our wake fan out as we leave behind not just the town where I served my term in purgatory but, I presume, the towns where they served theirs as well, if it’s true that we’ve already been on this ship long enough to gather many souls in my position, or former position, all of us perhaps no more than standard Americans at the ends of our ropes, prostrate inside ourselves as we beg sources unknown for rescue.

“Good morning, pseudo-Squimbops,” says a man in a tightly tailored gray suit with an earpiece and a wraparound wireless mic, his eyes wet and blinking as if unaccustomed to the abovedeck air. We all turn to face him, admiring his alligator-skin boots and thick, black mustache, as I pour any dawning familiarity he stirs in me into the rippling pool of Squimbop Cinema that now fills most of what I might otherwise have still considered my self.

“I said,” he repeats, louder this time, hitting what’s clearly a practiced note, his boots glowing in the sunlight, “I said . . . Welcome pseudo-Squimbops!” He raises his hands, as if expecting applause, which we haltingly deliver. I see myself clapping along with the others, all of our attention fixed on this man, who I can’t deny bears a resemblance to the rest of us, but looks—I can think of no better way to express it—more like us than we do.

“I am Professor Squimbop,” he announces, circling his hands like an orchestra conductor in what we take as a sign to gather around. “Much as I obey a Distant Master, you will obey me, for I was once, and not so long ago, a pseudo-Squimbop like you, lost in an Alaska of my own. And aren’t they all the same!” He scoffs, makes a show of recomposing himself, then adds, “but I found a way to become Real. I generated the power to transform and leave the Fever behind, and so, in time, will you. The process won’t be easy, but it will, if you’re willing to follow me all the way there, deep into the subterranean reaches of memory, prove possible. And if you aren’t,” he emits a forced laugh that causes his mic to glitch, “then, well, the Night Bus stops all up and down this coast. It will prove trivially easy to arrange passage for you back up north, and all of you know what happens there. So, let me hear it: who’s ready to become Real?”

I find myself cheering along with the others, at first quietly and then with moderate gusto and then, though I can hardly believe it, it seems I’m chanting and shrieking and dancing around the machinery on the upper deck, whooping and hollering in a circle, first in a voice I didn’t know I had and then in a voice I can’t be sure is mine, with the Professor at the very center, holding us in orbit as he closes his eyes and appears to listen to a yet-stranger voice, coming from much farther away.

As we chant, the landscape seems to melt and simmer, so that, by the time we’re done, the frigid waters we embarked into are a distant memory and we’re cruising through cool British Columbian fog and then southern Californian and then Hawaiian heat. We sail through bays and up rivers that bisect mountainous islands, into turquoise lagoons and mangrove swamps, cutting the engine and drifting for days at a time. Occasionally, the Professor directs the crew to disembark and bring huge drums of sand aboard, all stowed in a lower chamber to which none of us, as far as I can tell, has yet been granted admittance, even as the Professor comes for us one by one, manicured hand outstretched, saying only, “Time for your Past-Life Regression. You and only you. Just as you were conceived once, and then gestated, and then, upon being born, made Real . . . so will you be again now.”

With a wink and a curl of his mustache, he adds, “But for Real this time.”

These pseudo-Squimbops never appear again. Naturally, word begins to spread that they’ve been eaten by the Professor and his crew, or rendered for blubber to fuel the ship, but this causes no major ripple among those of us who remain. Although suspicion lingers as we sleep under the stars and the heavy sun, taking meals of fruit and nuts when they’re given, listening to the Professor’s brief, emphatic speeches when he chooses to make them, none of us attempts to spark the kind of conversation about our shared fate that, as I picture it, would only lead, rightly or wrongly, to mutiny.

We are, it is clear enough, too enervated to turn on one another, or, certainly, to band together against whatever scheme the Professor might be running, although it does occur to me that, in our desperation, we may well have boarded the wrong vessel, thereby forfeiting whatever chance we had at getting the Brothers Squimbop back on the road. At best, I now sometimes fear, this sorry episode will occupy a single side room in the Wing of Aborted Enterprises in an outbuilding of the Squimbop Media Center, if the Cooperstown City Council, in accordance with the bylaws of New York State or whatever shadow charter governs these things, ever manages to get it built.

Musing on an eternity spent in that particular limbo, we swing in the hammocks that used to be in short supply but are now more than adequate to our shrunken number and ask ourselves in silence when the day will come. We feel like lobsters in a tank, bobbing together, angry but impotent, our claws clasped shut, a numbed mass of consciousness capable only of the dullest hope and fear as the inevitable culmination of our boredom draws closer in the form of a single mega-lobster who, claws unclasped, roams the tank floor, reaping us one by one.

This lobster phase drags on, more and more reminiscent of my spell in Alaska. Our self-awareness coils ever more tightly inward as the number of heads it’s distributed among continues to shrink. The we on the upper decks again approaches the state of an I as the mega-lobster, embodied of course by the Professor, summons one pseudo-Squimbop after another, sometimes getting through several in one day and sometimes spending several days with each one, and then taking several days off—days spent gathering sand—until I’m the only one left, a development that I take as evidence that I was indeed the Real Squimbop all along, though I can’t suppress the suspicion that whoever was left would’ve felt the same way.

The Professor emerges onto the upper deck, earpiece and microphone in position, looks wistfully down at his alligator-skin boots, then up at the rows of empty hammocks, then smiles and beckons to me. “I always save the best for last,” he says, with a wink, before adding, “are you ready to be conceived anew?”

I nod, which causes him to shake his head and say, “I require verbal confirmation, my friend. This is a one-way trip to the Dust Bowl, so a yes or a no is the least I require.”

Mind already filling with what feel like ancestral memories of traipsing through the dust of the path that connected the cabin where I was born to the cities where my Brother and I became famous, I nod again, almost but not quite forgetting to add, “Yes,” just before the Professor is forced to drop the nice-guy act he’s barely kept up so far.

After this word is absorbed into or beyond his earpiece, he extends his hand, takes mine, and leads me down a steep, narrow staircase and into the ship’s cavernous interior, full, as I’d suspected, of grayish, dusty sand. He walks me through it, past a model gas station with a single tank and a handwritten sign that reads “For Ness County Farm Collective Members Only,” and a chrome billboard for “Dottie’s Soup Counter & Pie Rack,” and positions me in an armchair deep in the sand, making a “shhh” gesture when I open my mouth.

“Welcome to the Dust Bowl,” he whispers. “Authentic emanation point of the Brothers Squimbop. It is, at last, time to regain that which, over decades and decades upon the road, at large in the flux of the already-wide and ever-widening world, has been lost. Or,” he feigns forgetfulness, “has nearly been lost. For if it had been lost entirely, you would be beyond my help, and I would’ve left you in that frozen harbor you washed up in, waiting with your mouth open for the Night Bus to return. No,” he circles the chair here, covering his face in white pancake makeup and pulling off his sport coat to reveal a mime’s striped turtleneck underneath, no, he mimes, it has not been lost entirely. It remains in the dull bottom of your cerebral cortex, down on the ocean floor where movies seen in the depths of night recut themselves into what they truly are, only and always The True Story of the Brothers Squimbop, which no mortal editor can assemble . . . No, our story is not over yet. Together, we will fit the spool back onto the reel or, he grows giddy, hopping up and down, losing himself in the routine, the reel back onto the spool!

Either way, he mimes, drawing his energies back down to a simmer as he circles my chair one last time and blows sand in my face, let me tell you a story of the Dust Bowl. Your story and my story too, lost but not forgotten . . . and, as such, both my gift to you and your gift to me, as, together, we offer up our bodies to The True Story, so that it might recut itself around us back into its authentic form, at last healing the myriad deformities incurred by years of Squimbop Fever.

![]()

I close my eyes as deeply as the physics of my skull will permit. Behind them is the same Dust Bowl I’d begun to perceive while they were open, but larger now, more all-encompassing, and laden, suddenly, with sound, smell, savor, all the subtle stimuli that together boil into an atmosphere one can inhabit, move through, and, with sufficient force of will and submission to a larger psychic project, begin to consider Real.

Trudging into this project, already weary and parched, I train my eyes on the mime in the near distance as he bounces over dunes and through thorny scrub-brush, leaping into the air and kicking his heels together when the weather’s fine, bedding down in dry riverbeds when tornadoes render us helpless, and otherwise soldiering on for what feels like days, although the sun doesn’t rise or set, only wobbles around a fixed axis in the center of the sky. The landscape wobbles with it, jogging dim memories of the open ocean, but this seems impossibly distant, as far as the West Coast is from Kansas. The destination of a lifetime, I think, squinting to keep the mime centered in my vision. The site of all aspiration, the West Coast, the end of the line. I’ve made it this far, halfway at least . . . surely it will prove possible to keep going once I regroup and get my wits back about me.

I smile and then begin to laugh, unsure if I’ve made a joke or heard one. This uncertainty makes me laugh harder, so much so that I begin to suspect there was no joke before, but there is now, the eternal joke of whether, as I put it to an imaginary audience obscured behind the dust that’s now clotting in around me, the Brothers Squimbop are at root actors or directors . . . indeed, I mug, picking up on the mime’s mannerisms as I step out onto the stage of the frontier opera house in Abilene I’ve kept in mental storage for the better part of a century, the question is really whether we’re reprising a timeworn routine or making it up as we go, reminding all of you gathered here tonight that the Spirit of Adventure is alive in this nation, seeded here before your very eyes . . . and, beneath all this—the audience is in hysterics now after waiting a century in near silence, rolling in the dust, decomposing and coming back together as the plains boil with hilarity—the deeper question is whether there really are or even were any Brothers in the first place, if the legendary duo every existed, or if it’s only ever been me, alone in this wasteland for all time, neither living nor dead, neither near nor far, in relation to nothing at all, blindly following a mime who . . .

The mime swarms me as I begin to rave, pulling the horizon in with him like the thick, dusty flap of a circus tent, closing it around the intimate, candlelit scene inside. Evening falls across the broken porch slats of a one-story frontier cabin in Ness City, Kansas, he mimes. Year of 1934, year of hunger and thirst, the Crash a long way back, the War barely a glimmer up ahead . . .

Yes, we’ll post up here for a while. Here, until history compels our escape, our ship comes to anchor and our horses trudge no farther. We have, have we not, traveled long enough.

Nestled in his armpit, I allow the mime to lead me to the cabin’s front door and extend my arm with its hand attached to rap at the knocker. After a dead spell, a woman in a long black dress opens up and looks us over. When she makes eye contact, first with the mime and then with me, the tiniest glimmer of recognition plays across her face, as, I’m sure, it does across mine. Another life, I think, a dewy forest in deepest Bavaria, a village that, thanks to us, reduced itself to eggshells and cinder as it sank through time, back to the Dark Ages it had only lately emerged from. Another sweltering road, in another country, on another continent, this same woman, in the same black dress, leading a donkey, while my Brother and I, as thirsty then as we are now . . .

“Well?” she snaps, recognition draining from her face as the present asserts its total if temporary dominance. “Did you come to eat or come to gawk? Because I take in hobos for the one but not the other.”

The mime makes an elaborate show of mocking my hesitation, shifting his weight side to side in weepy impatience, yawning and tapping his mouth until, though I only feel more shaken than I did a moment ago, I get a provisional hold on myself and cross the threshold, trying to suppress the overwhelming suspicion that I won’t cross it again.

Inside, the woman induces us to sit around a narrow table, lit by more of the candles that light the whole scene. Our chairs rock with a distant oceanic pulse as she ladles out three bowls of chili and cuts three slices of hard white bread.

When she’s likewise taken her seat, we say a brief Grace in which she invokes the majesty of the Kansas wind and prays for rain. Then we begin to eat in silence as the mime entertains us with tales of the wild, weary Dust Bowl he’s come to know during his journey from Pittsburgh, where, he claims, he’d managed a sandpaper factory until the going got rough. He tells of cannibal hives in Kentucky and a trade in human molars in Tennessee, of telepathic leviathans beneath the Mississippi and a tree that bled sticky, sickening wine in uppermost Arkansas, potent enough to render that very tree hallucinatory in retrospect, so that no traveler could say for sure if it was there. Our chili dwindles and the woman pours us frugal shots of brown liquor as the mime dances around the kitchen, leaping up onto the counters and making a prop of his busted chair as he introduces us to a songster in Olathe who wrote murder ballads for a dollar apiece, the only hitch being that he required the salient events to be acted out before his eyes—and not merely acted out, the mime adds, with a leer—and then he’s onto a pair of ex-boxers who offered their bruised faces as stand-ins for local personal injury lawyers in upward of two hundred Missouri towns, claiming variably to be the Law Offices of Stevens & Sandino, or Lewis & Willmerdorf, or even Fujiyama & Stephanopoulos, and a nunnery in Chase County where all the nuns created cloth facsimiles of themselves in order to trick Death into taking these and leaving their flesh in peace, the only problem being that the facsimiles grew so convincing that the nuns were likewise fooled, so that perhaps this nunnery was, or was soon to be, no more than a cloth museum, sterile as a marble shrine on a mountaintop in Armenia, awaiting the rival cults that would in time form to revere and deny what had happened there.

The mime takes a victory lap around the kitchen upon concluding this story, and just as he shows signs of beginning the next, the black-clad woman rises, gathers him bouncing under her arm, and, leaving me alone with my chili bowl, sighs, “Excuse us, it’s time for the Primal Scene.” She doesn’t add again, but her sigh more than conveys that she thought it.

I remain in position a moment longer, jilted surprise on my face as if I were the mime now, wearing an expression that someone else painted on, but when lewd, magnified shadows begin to play across the walls, I tiptoe past the room they’re coming from, more frightened of creaking the floorboards than I have any good reason to be. Frozen just outside the open door, I watch the mime and the black-clad woman perform the Primal Scene, its shadows now intertwined with my own, so that I feel myself being pulled in and, soon, cannot be sure whether I’m in the hall by myself or in the room with them. My attention swivels between the bodies and their shadows, back and forth, until my eyes blur and I sink into another memory, that of my Brother and me on the open road, years ago or years from now, behind a Shoney’s in El Centro, ribbing each other about this very scene, always claiming, to the point of lurid mania, to be the other’s father. A smile spreads across my face, growing painfully wide and wider still, as if extending beyond my head, until I explode in a fit of hysterics that I just barely manage to contain by hugging my sides and tiptoeing down the rocking hall, through ever more vivid shadow play, into what is clearly the Bachelor’s Cell, made up identically to the room I occupied in Alaska, the windows still full of the white light from the grocery store across the street.

The cot in the Bachelor’s Cell squeaks when I collapse upon it and, letting go of my sides, the laughter spills out of me and into the coarse, cigar-burned bedding. I laugh, exaggerating my expressions just as the mime would have, while the cell rocks and the shadows follow me, twisting and twining beyond all geometric sense, projecting every conceivable—no pun intended, I smirk, slapping my thighs—permutation of the Primal Scene that my Brother and I joked about so long ago, and all I can think, as the mad repetition of the shadows dulls my faculties, is that I wish he were here with me now, to see such crude living proof of the routine that sustained us so long, throughout so many dismal teaching gigs along the backmost and bottommost edges of the nation, in which I was his father, much as, of course, he was mine.

![]()

I awaken to a baby’s sobbing, so loud and regular that it seems impossible to attribute to a single source. When does it breathe? I wonder, as I lean up on my elbows in the cot that I only now remember falling asleep in. I yawn and feel the Bachelor’s Cell rock and tip me back to the lost oceanic expanse of the womb, the all-encompassing aqueous eternity that feels at once terribly far away and terribly near at hand, as if I’ve only just now been expelled from it with a directive to ply my trade upon the surface of the planet for as long as anyone there will have me, weaving my saga into the fabric of the nation before—the warning is at once frighteningly direct and maddeningly opaque—it is, once again, too late.

As the sobbing continues, I rise, yawn, pee in a pot, and resolve to creak into the kitchen and face there whatever new turn this episode has taken. I press my hands against the walls of the cabin, making my way out of my solitude as slowly as I can while also miming this same emergence, squeezing my way out as if from the womb, and blinking in what I pretend is the first sunlight I’ve ever seen.

In the kitchen, I surface upon the mime ladling gruel into bowls for the black-clad woman and two small boys, who sup desperately, licking the last meager crumbs of brown sugar from the edges of their too-large spoons. No one admires my routine or even looks my way until I tramp over to the table, feeling my bones thicken and my skin sag, and look down at the cracked wood where no place has been set for me. I tramp out to the shed with practiced heaviness and return with a cracked spare stool, where I sit until the mime has no choice but to spoon what remains into the bowl he’d been eating from, and place it with a scowl before me. He mimes disgust while I mime embarrassment, doing my face up into an impression of a dubious lodger who’s long outstayed his welcome. Though it feels tired, our routine now elicits modest laughs from the woman and the boys, enough that I can’t suppress a blush of pride to know I haven’t yet lost my touch.

Still blushing, I watch the dirty spoon tremble as it conveys my portion to my mouth while my eyes likewise tremble with crocodile tears, and the laughter simmers down and the morning approaches its next phase.

Don’t get too comfortable here, stranger, the mime mimes as he takes my bowl before I’m finished and tosses it into a pail of suds on the counter. He tips the edge of his fedora, winks, and sets off, out the door to, as I imagine it, ply the dusty trails between here and Ransom in search of whatever work is to be found. Back in the cabin, the day stretches ahead of us, the black-clad woman and the two boys and me, all of us straining, it seems, to prolong a routine that’s long since abdicated its claim to relevance without yet nominating a successor.

Save me from this stasis, I beseech the three of them, as they traipse through the cabin and out to the yard in back, the boys whipping each other with wet towels while the mother picks what few scraggly pears protrude from the trees that verge onto a field behind their property, or that which they occupy. Release me, for my Past-Life Regression has only just begun, I wish to tell them, but I know the words, even if I found a way to say them, would fall on deaf ears. So I mime the day away, trying to devise a routine in which I leave this stagnation behind and travel on with my head held high—in the routine, I’m more than able to travel alone, forsaking whatever need for reunion initially compelled me aboard that ship in Alaska—but, although I do manage to walk down the front steps several times, some principle of the larger scenario will not allow me to breech the sidewalk. Indeed, each time I try, laughter rises in the background, the routine growing steadily more ridiculous with repetition as, somewhere in the dark at the edge of my psyche, Tommy Bruno scoops fresh popcorn into a series of cardboard containers and smiles his tired smile while a series of guests makes its way in to behold my leashed circuit in glorious black and white.

Thus the day goes on, and thus the days go on, the boys growing steadily while I seem to shrink, losing my orientation within the makeshift family that the mime returns to late each evening, launching always into the same hard-luck show as the night before, unaware of or indifferent to the boredom that it now provokes in his supposed wife and children, to say nothing of the strained relationship that’s evolved between him and me, paterfamilias and bachelor uncle, one Brother gone straight, the other back from the past to skew it all sideways again.

![]()

One night, several more years into this arrangement, after the others have retired and I’ve taken it upon myself to scrub the dishes stacked in the washbasin, I hear the mime creep up behind me and turn to see his face painted with violent red streaks and green fanged dentures gleaming in the moonlight. He grins, pulls the washrag from my hands, and motions for me to sit.

I comply. He sits across from me, dancing his legs back and forth on the kitchen floor, warming up for what I can tell will be a routine he’s had planned, perhaps from the beginning, for this precise moment, neither a day earlier nor a day later, as if, seen from a more distant vantage—that of Tommy Bruno, eternally unchanging save for his random alternation of black and white bowties and the nights on which he appears to be drunk on more than cinema—all of this had been a single elongated episode, and now, right on time, we’ve reached the finale, stasis breaking at last not because of any internal development but simply because the appointed moment has arrived, and the theater must be emptied, cleaned, and made ready for the next showing.

Go to your cell and get your things, he mimes. Then—his made-up eyes come to rest on the turkey knife on the counter, with which the black-clad woman slaughtered an ancient bird in the sink—it will be time for you and I to take our walk, as Brothers one last time.

Compelled by the same logic of imminent climax that has just compelled him, I get up with a flourish, turn, and slump down the hall, adding weight to each reluctant step until I’m nearly stomping on the loose floorboards.

As I wind my way toward the cell in this fashion, past the wall where the shadows of the Primal Scene still flicker like a property of the wood itself, something else comes to mind. A final errand to attend to, perhaps my first since the Past-Life Regression began. I check behind me, wary of the mime’s roving gaze, and then steal into the room where the boys are sleeping. I stand in the corner, hidden in shadow, and watch their faces, nearly identical and yet not quite, one already more dominant, the other a shriveled version thereof. Just like, I can’t help thinking, though it feels like overkill, the surest way to neuter a joke, the mime and me.

I hit myself in the forehead and mime a belly laugh at the obviousness of this thought. Then I lean over them, feeling the fullness of my role as their bastard uncle come surging up from my core, and say, breaking my silence for what feels like the first time since Alaska, “From this point forward, you are the Brothers Squimbop. Jim and Joe, blessed and cursed to ply the interior of the nation in every form it has left to take, and to deform it into yet further permutations from there, kneading the land into a bastion of the very forces you embody, so that you will exist always as both destroyers and destroyed, bastards bastardizing the order of things until it—”

Footsteps rush up the hall, a desperate, racing violence coming to purge me from where I don’t belong, the mad pervert uncle loose in the room where the precious boys are sleeping, about to seed in their past a violation so profound that they’ll never quite . . .

Knowing all this because it is in some sense the story I’m telling, I lean over the bed and shout, spittle flying from my lips, “Live on so that we might live on too, so that we all, all of this, the great wheel we roll within, might not stop here, as if it’d never started . . . Roll on, let the legend of the Brothers Squimbop roll into the future and not lodge here in the Dust Bowl, to which I never would’ve returned had I not—”

The mime’s hands are around my neck, the turkey knife stretched between them, realer than anything I’ve ever felt or expected ever to feel.

![]()

The Brothers Squimbop, Jim and Joe, jolted upright in bed as their father dispatched the last of the pervert uncle whose long, lecherous presence throughout the years of their youth accounted in no small part for the dim view they’d already taken on humanity, the viper ethos that would, before very long at all, serve as catalyst for the adolescent exploits that would in turn, not long after that, serve as seedbed for the growing reach of their legend, two damaged Kansas farmboys at large on the high prairie, raising more hell than any pseudo-Squimbop could ever have dreamt possible, magnetizing a torrent of attention and ramifying narrative so colossal that any attempt to encompass it within a Media Center in Cooperstown, New York, would be a fool’s errand of such magnitude that the City Council, when presented with the proposal, would only laugh at the naivete inherent in this most American of all ambitions, still the nation’s greatest asset, after so many centuries of frenzy and flux.

They marinated a little longer, there in bed and then at the table and in the fields out back, scrounging for sustenance as their sweat thickened into a shell around their growing frames. The black-clad woman came and went from their vision, resentful of the burden of bearing them, thrust upon her more times than she could count, even if this time, like every time, was the first, and hence, though the paradox had long ago maddened and then begun to bore her, the only.

Then came a muted Last Supper, in which the black-clad woman killed her prize chicken, fried it in a pan, and served it with honey, butter, and the Brothers’ favorite cornbread, dotted with green peppers and baked in a skillet in the oven. The walls turned to curtains again and blew in close, and the lighting framed the three of them suggestively, as they sat rocking on the precipice of a new era. They could all imagine this very scene rendered into a folk painting on the wall behind them, and, though none turned to check, it soon grew impossible to say it wasn’t hanging there already.

The Brothers’ mother regarded them from across the table that she knew she would from then on occupy alone with the painting, sinking into history as the legend grew and, like all legends, obscured its true origin in layer upon layer of eager hearsay, until she’d be nothing save for what drunken strangers in loud rooms said she was, at least until the mime and uncle darkened her door again, and, buried in memory and half-yearning to surface from it, she again invited them in, provided they’d come to eat and not to gawk.

She looked from Jim to Joe and Joe to Jim, committing their faces to memory and building, insofar as anyone could, a bulwark against the infinite revisions that would soon be relayed back to her, in print and newsreel and painting after painting, and, before very long at all, on the television sets that first one and then all of her neighbors would turn out to have bought in secret, just as the War was ramping up. Then she said a prayer inside her head, admitting to herself that she loved them even if, in some regard that could never be untangled, they weren’t really her sons, only beings who had passed through her on their way between worlds, and then she excused herself, stooped and rocking down the hallway beneath the weight of knowing that she would never be given the credit she’d earned.

The Brothers left soon after she was gone. Finishing the drumsticks that were already in hand, they wiped their fingers on their corduroys and packed modest satchels from the ill-fitting clothing strewn about the room they’d been fledged in, laced up the boots that had served them well enough so far, even if they’d soon be outgrown, and walked down the road that led, in the direction they’d begun to travel, away from the cabin that the Past-Life Regression had seen fit to provide, and out past Ransom, Kansas, crossing a county line they’d never crossed before.

As they sallied forth, each Brother began to work to solidify what he was leaving behind, adding details where details were missing—a stifling country schoolhouse where he’d been taught the rudiments of Greek and Latin along with Eliot, Hopkins, and Poe by a saintly schoolmistress whose belief in the education of minors was a godsend unlikely to be repeated later in life; an almost-chaste summer romance lit by fireflies and a moon full to bursting, though shadowed also with the heartache of knowing that in September her family was moving to Lincoln; a sinister yet charismatic uncle who, although he’d done unforgivable things in the night, had also revealed the secrets of card counting and the power of suggestion—and guarding these against the inevitable discrepancies in whatever account his Brother was forming in the same sacred moments. More than anything, they worked to clear space in memory, opening as many spare rooms as they could find, suddenly aware, as they put one foot in front of the other toward the West, that only in the Media Center of these spare rooms would any of what had happened and was about to happen achieve any cohesion at all.

They began to suspect one another as the night wore on, each keeping more and more to himself, a hand clamped over his lips for fear of muttering any part of his ruminations aloud, and thus they trudged, increasingly out of breath, through lunar canyons and beneath sharp outcroppings of glinting limestone, across open tundra and fenced-in paddocks dotted with sleeping horses, only just beginning to gain a sense of how large the world they’d spilled out into, in search of the future, truly was.

It wasn’t until the first light began to flicker in the distant East, lapping at their heels and then the backs of their legs, that they were forced to stop, take water, and gnaw the drumsticks they’d packed. As they did, still wary of making eye contact with one another, a rustling in the creosote a few feet from where they stood stole their attention, so that they had no choice but to amble over to where it was coming from, drumsticks dangling by their sides.

By this point, the sun had risen high enough that they could see the tableau in all its ramshackle, rustic glory: the mime slitting their pervert uncle’s throat with a turkey knife, while the uncle groaned, “Boys, never forget, I’m your real father, sent here from deepest Alaska to seed you. To thread the legend back onto the spool so that it might not terminate in blackest arctic gloom, where Tommy Bruno will only ever . . . But—” he spluttered as the mime dragged the turkey knife back and forth, graceful as a cellist bowing out Bach, “you mustn’t tarry, lest you end up like me. There are thousands, perhaps millions of murders to your names. A Fever precedes you that nothing can describe. You won’t outrun the forces that are seeking you, even if it’s not altogether you they’re seeking. The crimes occurred and it is you who must pay.”

The tableau stopped, and the Brothers began to figure that the cycle was restarting, when, instead, the pervert uncle gasped, “Let nothing stop your approach to Dodge City. Trudge on, no matter how vastly they swarm you, but make haste, for others are trudging the same path as we speak. Other iterations, other Past-Life Regressions, pilgrims on the road, too numerous to reckon, and only one biopic will be made. See to it that it’s yours, pledge yourselves to cinema and you will never pay for what you’ve done, you will never—”

Here the tableau stopped again and a voice from behind them, sudden enough that they both jumped in unison—perhaps their first coordinated motion, a harbinger of great things to come if, as the tableau urged, they made it to Dodge City before the law caught up with them—said, “Speaking of paying, that’ll be a nickel, boys. Pay up and you can pull the curtain back for free.”

They turned to regard a farmgirl who stood all of three feet tall, holding a power cord that stretched between her and a distant tin shed beside the farmhouse she surely inhabited, if she inhabited anyplace on earth. The length of the cord corresponded to the length of time they stood there, insofar as neither Brother felt compelled to respond until his eyes had traced the cord all the way from where they stood to its distant terminus, and back, and, though they could sense that this was pushing their luck, back and forth a second time as well.

After this was complete, they resolved to regard her—she’d gone nearly as still as the mime-and-uncle show whose power she’d cut—and, clearing their throats with a confidence they’d never expressed before, said, “Show us the curtain.”

She snapped back to attention and bundled the cord more steadily in her arms, nearly vanishing behind it so that only her head appeared above the coil, with her feet peeping out below. The Brothers followed in her dust, past discarded pieces of the mime-and-uncle show—broken turkey knives, cracked dentures, weedy bald spots—as, in the distance, the footsteps of other duos on the Road to Dodge City begin to boil, like locusts about to make landfall. The Brothers hurried toward the shed where the curtain was housed, at once fearful of losing time and determined to get their money’s worth, even if they hadn’t paid yet.

Following the cord, the farmgirl led them past the rest of the equipment, over a metal grate that traversed a pit of fur and manure, and into the shed, within which a holographic wizard hovered in nervous anticipation. “I am the great and wonderful Wizard of—” he sighed, as Joe Squimbop, even more confident than a moment ago, reached past his Brother to yank the curtain open, revealing a small, bespectacled man behind a typewriter-sized console.

He peered out, startled, and said, “Gina, have they paid yet?”

The farmgirl shook her head and the room contracted, growing clammy as the mist the wizard had been projected through began to condense on the floor. “You watched the mime-and-uncle show?” the man asked, rubbing his forehead and sighing, like he was already near his emotional limit for the day.

The Brothers nodded in unison, and then, also in unison, joined suddenly by clarity of purpose, said, “Dodge City. We’re on our way there, to sell our life rights. We’re the Brothers Squimbop. Famous outlaws. Drifters, hooligans, gypsy tricksters. Call us what you will, we have millions of murders to our name. The biopic must get this right. Which way is quickest?”

The man sucked his face into a grimace, then exhaled in what was almost a laugh. “You’re the Brothers Squimbop!” Now he laughed outright. “You know how many times I’ve heard that today? And I can still taste my breakfast! And this is just one shed-show of dozens!” He laughed so hard the Brothers couldn’t help laughing too, while Gina stood back, fidgeting with the cord.

In this commotion, Joe dropped the edge of the curtain he’d still been holding. As soon as it fell between them and the man at the console, the wizard reappeared, green and garish in the stillness of the shed, bouncing with the kind of jagged energy that only flares up in moments of extreme exhaustion. “Dodge City?” it boomed, swelling so that its head alone filled all the space between the Brothers and the door, backing Gina into a rake-strewn corner. “Behind this curtain lies the road, it’s the shortest way by far, but be warned, you won’t be on it alone. I owe no special favor to you, nor do I have any reason to imagine you two, alone among the thousands, are the Real Brothers Squimbop. The ranks of pseudo-Squimbops, as your progenitors knew and you will soon learn, are nearly infinite, and the culling they are bound to suffer will be gruesome beyond imagining.”

The head shook in silent laughter, boiling in a loop while the Brothers deliberated, torn between soldiering on along the hot, dry road they’d set out upon last night, charged up and ready to commit the legendary crimes it now seemed they’d already committed, and peeling the curtain aside a second time, thereby taking their chances on the shortcut.

“Pay us that nickel,” Gina said, from the corner, “or you’re going to bear a curse that—”

If only to be free of additional threat, Jim reached past his Brother, grabbed the edge of the curtain, and hauled it aside again to reveal a dusty path choked with duos, so thick it was impossible to distinguish one from another. Some had fallen on the yellow-brick road, while the rest laughed and bickered and chattered as they sped along, speaking in high tones of the redemption they sought on the backlots and in the gilded cinema palaces of the world-famous Dodge City Film Industry. Some acted out satires of this road scene with hand puppets and marionettes, while others formed harmonica and ukulele bands to sing folk songs about the bloody, bloody Road to Dodge City, many of which the Brothers found they already knew.

Suddenly fearing the loss of their last tether to the Real, they recoiled and even fought, for an instant, to remain on the near side of the curtain, with their memories of the cabin, the mime-and-uncle show, and the life of crime they’d embarked upon last night. But Gina, who’d surely seen this same hesitation many times today and could tell she’d never get her nickel, leapt behind them with a rake, prodding first Jim and then Joe over the threshold, beyond the curtain and into the sweat of mummers and the clang of war drums, along the bloody, bloody Road to Dodge City. ![]()

David Leo Rice is a writer living in New York City. His books include A Room in Dodge City, A Room in Dodge City: Vol. 2, Angel House, and Drifter: Stories. His next novel, The New House, is forthcoming.

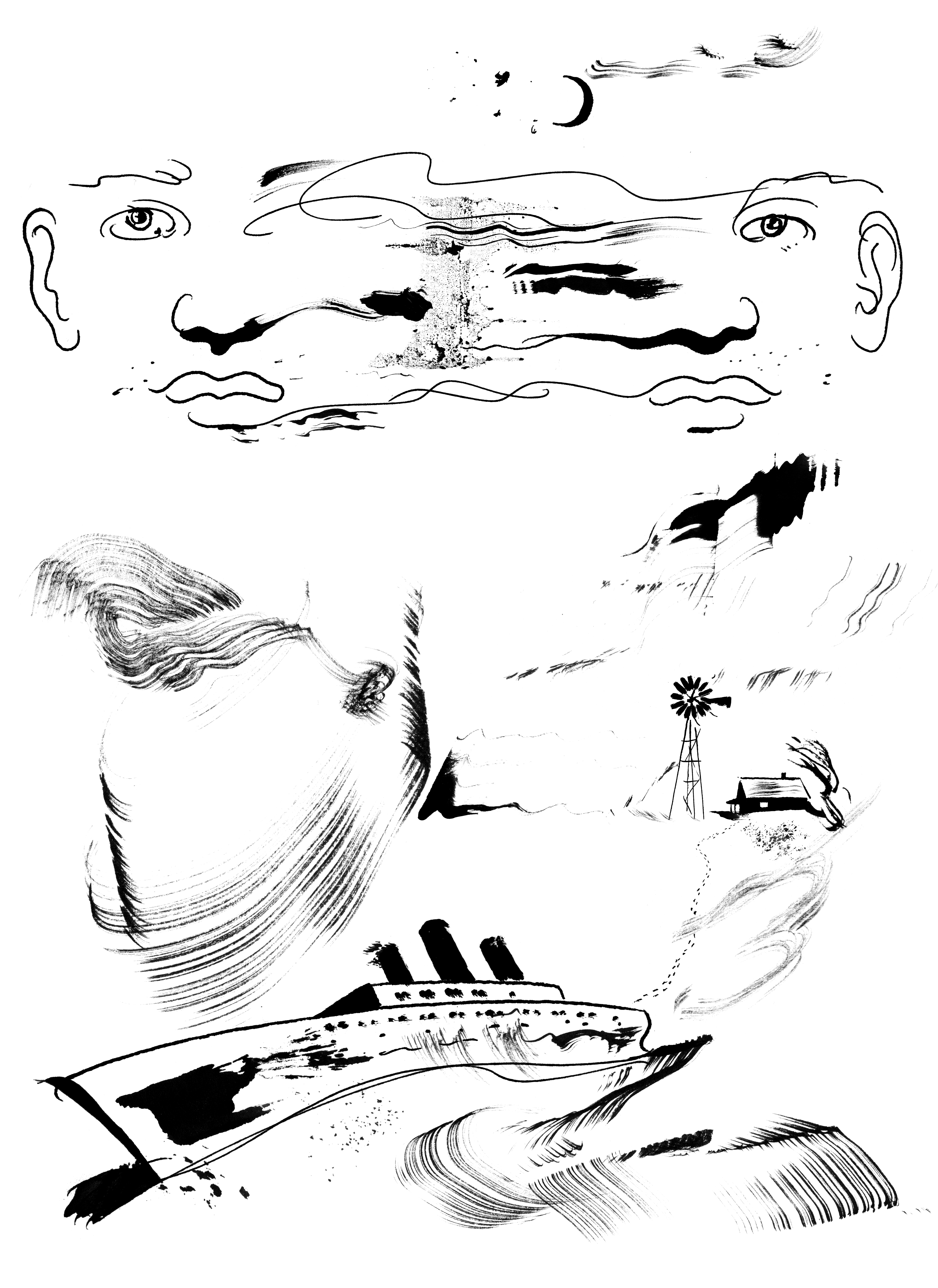

Illustration: Jan Robert Duennweller