I rest on a bed of fine dust beneath the fridge with my mother and siblings, hidden away from the bright lights and loud swell of music that vibrates the floorboards beneath us. As the moon rises outside, its glow slicing through the open curtains of the patio door at the rear of the kitchen’s dining area, the roar of the people grows louder, more raucous. There are many more of them than the human woman and girl child we are used to sharing our home with, and they have wrapped themselves in brightly colored fabrics and painted their skin or covered their faces with strange masks. Mother says it’s a Halloween party, a rare event that will yield sweets enough to feed us all. Though I am excited by the prospect of such a feast, I know we must be patient.

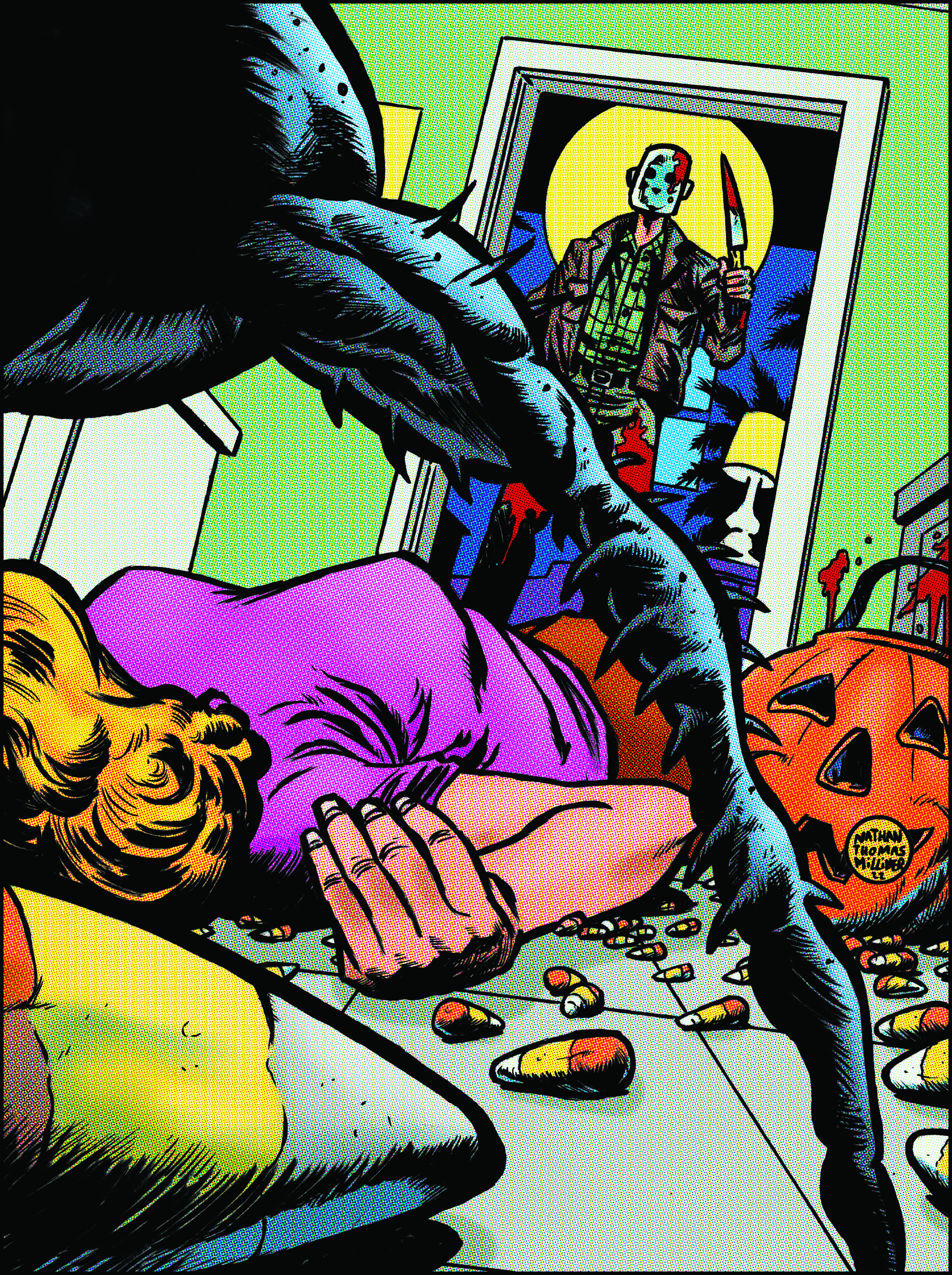

The voices of the partygoers build to a crescendo of shrieks and screams, until they disappear one by one. The repetitive boom underlying the beat of the music finally stops, and the strobing lights go mercifully dim. Mother leads us out from our hiding spot into the cool dark. The only light is the flicker of a dying candle in the carved head of a pumpkin. I survey the room in one look, my eyes taking in three hundred and sixty degrees. Cupboards topped with countertops that often hold valuable crumbs tower beside me, and the dining room chairs that lead to a table potentially holding dishes of half-eaten food sit empty, but I ignore my usual feasting spots. Tonight won’t require climbing.

Mother was right about the sweets, and I follow my brothers and sisters to the scent of the sugary candy strewn across the floor, my six legs propelling me in a soundless scurry. I probe the air with thin antennae and locate a treat unclaimed by my siblings, a banded triangle of pure sugar that gives way before my mandibles. The candy is sweet and nourishing, a satisfying meal, but I scent another, different flavor close by and venture farther.

I step over the half-eaten treat, toward a human woman lying prone before me, the woman who shares our home. I scamper closer, my legs encountering a pool of warm blood that I sample as I move through it. A snarl of hair trails through the blood, and I maneuver across the strands, reaching soft skin. My feet leave footprints like the pricks of a needle across her pale cheek as I make my way toward her eyes, which stare upward, wide and glassy. Her scent and the feel of her flesh is familiar to me. She is a heavy sleeper, unlike the girl child, who tosses and turns, and when there are no food scraps, I feed on her fingernails.

Tonight, though, the woman is not sleeping, so there is no need for me to be gentle as I feast on her eyelashes, tugging them from her lids and nibbling on the mites that call the follicles home. This treat rivals even the fun-sized candy peppering the floor. A current of air stirs the cerci on the underside of my shell at the same moment that a brilliant light spoils the darkness. I turn to flee and glimpse a man in a mask, smooth and featureless, raising his booted foot and bringing it down on my fleeing mother, my brothers, my sisters. Their exoskeletons crunch beneath his weight, their creamy insides spurting out to mingle with spatters of blood.

Our numbers are our only advantage, there are too many of us. We scuttle over candy and prone bodies, back to the darkness of our safe place beneath the fridge. I savor the remnants of sugar that stick to my mandibles and front feet as I watch the man. He crouches on the floor beside the woman and removes his mask, then strokes her face. He is familiar to me, this human man who used to live in our home, too, and would disturb us with his shouts and broken things. But then he was gone, has been gone.

He uses a long, serrated knife to dismember the woman’s body, wrapping each piece in plastic. Next he moves to the girl child, who isn’t tossing any longer, isn’t sleeping tonight either. There are other dead humans, ten at least, and he handles each of them more quickly, with less care than the woman and child. My own family litters the floor among the spilled candy, but I don’t mourn them. I only wait and watch, knowing that darkness will fall again and there will be plenty left to eat. ![]()

Angela Sylvaine is a self-proclaimed cheerful goth who writes horror fiction and poetry. Her debut novella, Chopping Spree (2021), is an homage to 1980s slashers and mall culture. Angela’s short fiction has appeared in various publications, including Dark Recesses, Places We Fear to Tread, and The NoSleep Podcast. Her poetry has appeared in such publications as Under Her Skin and Monstroddities.

Illustration: Nathan Milliner