White Trash Gospel | A Conversation with Elle Nash

Interviews

By Troy James Weaver

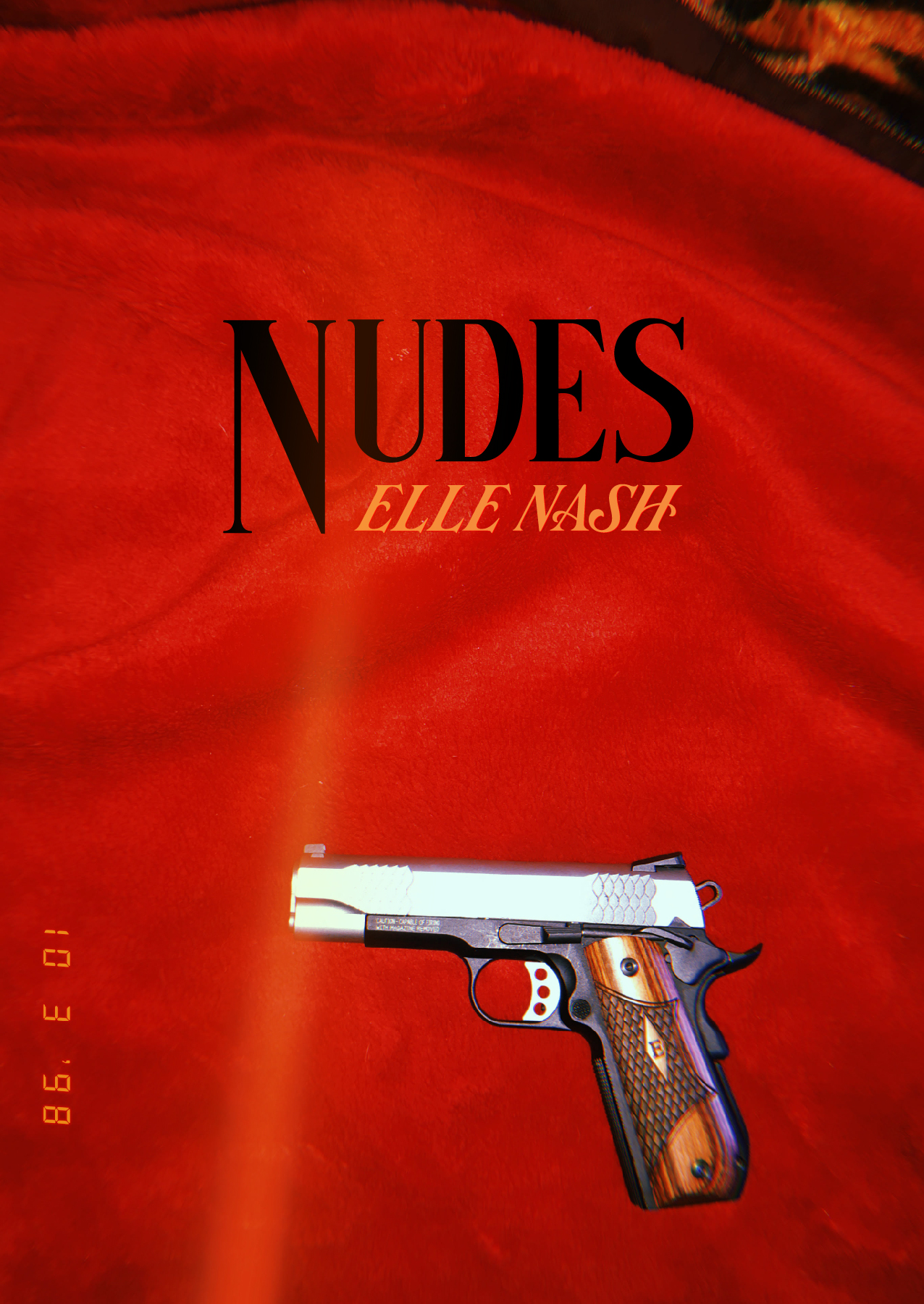

Elle Nash’s new collection Nudes (SF/LD) is chock-full of characters who are fearful, weak, powerful, powerless, and stuck. Broken people trying to find their way, whether it be on the internet or in a trailer park. These are scenes from the other side of the tracks—white trash gospel, pulling us through a haze of bitter cigarette smoke and the sweet fumes of a freshly opened Faygo. There is a strained beauty to these stories. Imagine high winds pushing against stained glass, threatening a crack; imagine that stained glass shattering and reassembling itself on the spot. Small miracles happen here. The prose is minimal, crystalline, multi-colored. Like a transgressive Raymond Carver who listens to Nu Metal, Elle Nash isn’t only a great writer, she’s also someone to watch, admire, and learn from.

Troy James Weaver: How long did the stories in Nudes take you to finish? Were you intending to assemble these stories in a collection from the outset?

Elle Nash: Some of these stories I started writing when I began to explore how to write fiction in a more intentional way, as early as 2013 or so. I started taking writing workshops and never thought that one day I would actually have a complete collection of stories. I was just writing. A book wasn’t something that had really occurred to me, even after having written several stories, really, as I’d just been focusing so much on finishing my first novel and then thinking of all these other novel ideas. When [SF/LD editor] Elizabeth [Ellen] asked, I started pulling together what I had, all these loose-linked stories, to see if I could start working on them more intently.

TJW: I’ve been astounded to learn that you hadn’t read Dennis Cooper’s work until recently. You seem like kin, only in different modes. Your work is very interior and so is his. But I feel like your work moves from inside then outward then back in. His moves from outward to the inside and stays there. But there’s a certain similarity that I cant put my finger on. Like you’re both constructing spells, but you each have your own approach to how far you go with the fantasy thing. Are you into Cooper now, having written these pieces before you knew of him? Does the connection make sense? Am I crazy? Don’t answer that.

EN: Oh my god, I know. I don’t know how I hadn’t come across his work before; I read A.M. Homes in early 2020 and was seeking out other transgressive works as I was finishing this novel manuscript I was working on. I think I ran across a Paris Review interview with him—I had known who he was by then, sort of, like I knew he was an author who wrote about particular kinds of subjects, I had known about the George Miles cycle, but hadn’t taken the time to read it. After that interview I felt convinced I needed to and bought like five of his books and just read through all of them obsessively last summer during lockdown. I did not expect to read what I read, I think. I don’t know why. I’m glad I didn’t, it was like the French phrase that describes love at first sight—a shot of lightning. Something about his work begs me to continue, to finish the book in a day if I can. I’m reading My Loose Thread right now and have a million other things I should be doing but I can’t put it down. I think his work just completely rearranges what is possible in a work of fiction, for me anyway. It makes me want to eschew the possibility of ever being mainstream or making a living writing and just say fuck it and write deep into the things I want to explore but am scared of exploring. I appreciate you make even a minute connection between our work. Since discovering Cooper, he’s become like a new hero to me.

TJW: How did the different (but all sexual) names for Nudes’ sections come about? Is that a play on the vulnerability we have in the greater scheme of things, the fetishization of being alive? Like struggle is sexy and dying can be sexy? Dominating, dominated, indifferent, etc.? Is living sexy, no matter how ugly it gets?

EN: I love that you describe being alive as a possible fetish. I am into that. “Being alive is my kink.” Sounds like something a sober person would say. The different names for the sections came about because I was thinking about the cross-section of obscenity and art. Maybe in some ways it’s because I tend to write from the body / about sex and so I couldn’t think of any other way of organizing these sections. “Fluffers” set the scene, “Yuri” is about emotional intimacy, “Pukkaki” is about the fear of rejection, “Moneyshot” is kind of like a climax, “POV” is meant to feel more voyeuristic and observant, and “Snuff” is the natural end. Death. I guess in a way these sections really reflect a kind of dance people have with each other, in relationships or sex or with life in general. Is living sexy? Yeah, totally. It is. Even the worst parts can be good because at least you are feeling something. It’s a clever way to make art, having experiences.

TJW: You explore dark themes—whatever that means, like, we are all dark because we are human—but you do it in so many different ways. How do you do you manage going in so deep in so many different ways: stylistically, with point of view, etc.?

EN: I probably go in deep because I am in my head way too much. Sometimes it’s just easy for me to get overwhelmed with feelings: mine, others, people around me. I kind of feel like a sponge in that way. And maybe the only way to resolve the feelings I have is by exploring facets of them through stories.

TJW: At what point in your life did you realize you wanted to be a writer? When did you realize you wanted to be a published writer?

EN: In high school I solidified my identity as a “writer,” I think. I had discovered poetry, had these dreams of what a writing “career” would look like. But I didn’t really know anything about getting published or how one does that until much later, when I started taking writing workshops and meeting other writers. I didn’t know anything about the indie lit community yet, or how the whole ecosystem really worked; the only books I’d read had been from major publishers. My favorite writer at the time was Chuck Palahniuk, his early stuff. I read about his life online, learned about how he’d taken the Dangerous Writing workshop in the 90s, learning from Tom Spanbauer. It was there, in Tom’s workshop, that I really learned more about independent literature, saw how publishing stuff was possible for me too.

TJW: You have a pretty busy life. How do you find the time to write?

EN: Locking myself in the same room for a few hours a day, early in the morning. Losing sleep, sometimes, to do it. Spending less time living and too much time writing, which I did for like three years straight. I would probably be more present in my life if I did not write. But, I like it. It’s a balance. Probably not everyone in my life likes that. But I don’t know—alone time, that time, is kind of the cost I pay for doing what I want. It’s a complex thing.

TJW: What do you want from all of this? I ask this because it’s a question I ask myself constantly.

EN: I don’t know, some semblance of satisfaction, maybe. Or a kind of liberation. I’m in pursuit of that—liberation, my mind feeling freed from the constraints of normal life, real life. That’s what I want. Understanding, maybe. And of course I want to feel validated the way anyone does.

TJW: Do you have to have an ideal environment where you do your writing? Any rituals? I like to be comfortable, whether in my bed or on the couch. I also like to drink tea.

EN: My ideal environment is usually in silence, early in the morning. With coffee. I like to write until my body starts to get restless, I can’t deal with not eating anymore, or my brain starts to get tired.

TJW: Do you listen to music while writing? If so, what are some of the bands you like to listen to? Do you think it helps the writing in any way?

EN: When I wrote Animals Eat Each Other, I listened to the same songs on repeat. A lot of The Weeknd. For my short stories and this next novel, I usually wrote in silence, mostly because my child would be asleep in the next room, and I didn’t want her to wake up. Sometimes I wrote whenever I could—with kids’ songs blasting in the background, with constant interruptions, in five minute intervals, whatever. I’ve gotten good at tuning out in order to push forward. I love to drive around and listen to the same songs on repeat, thinking about my stories. That whole thing about “doing nothing”—that’s when I have my genius moments. I think songs are great for pulling you back into a specific frame of mind, which is especially helpful when you’re writing a novel. I listen to a lot of the same songs on repeat so much, when I’m driving, to keep that frame of mind at the surface. Thinking about characters or whatever: moments, feelings, scenes. Right now what’s on repeat for me is “Tension” by Vök, a lot of Banks, Ghostemane, Killstation, Lil Peep. Maybe that’s just my excuse to listen to sad music.

TJW: Do you think the small press/indie publishing scene has changed at all since your first book came out in 2018? How so?

EN: I would say one way that the scene has evolved is I feel there are a few transgressive lit spaces that have grown quite a bit. That feels promising. I want to be a part of that.

TJW: Have you ever written a story front to back and been satisfied with the results?

EN: Yes, when I wrote the title story to Nudes. I don’t recall doing too much editing on it; I felt enamored with it. I read it over and over again trying to see if it was the way I wanted it to be and I couldn’t find a lot to change. That was really nice—like a fluke, some kind of post-story glow.

TJW: Do you think where you live—place—is important to what gets put to the page?

EN: I grew up in a military family. We moved around constantly. I don’t have that sense of “hometown” the way most people do. I am always very conscious of where I live, of my space, because I’m so used to changing it often. If I stay in one place for too long I become restless, and I think that shows up in my work. Maybe staying in one place for too long forces me to write more because then I’m spending more time in fake worlds than in the real world, which is where I don’t want to be. I love moving to a new place, though, too, because I get to notice everything new. When I moved back to Colorado Springs at the beginning of 2020, I had already lived here during my adolescence. But because I’d been away for over a decade, it was all new to me. I noticed the mountains’ intensity for the first time, something I never cared about when I was sixteen, seventeen. I noticed the weather on the mountain every single day. I noticed the sun a lot more. I noticed the seasons changing. I noticed the streets, I noticed what people were wearing, I noticed dispensaries and Starbucks and funeral homes. I’m still noticing all of it because I’ve only been here a year and haven’t been out much. I drive to places where I don’t even know what they are. I drive through the parks—here, we have a couple of natural parks that you can hike in, right in the city. I never noticed this stuff when I lived here before. I used to just drive to these places at night to do drugs or go to raves. I never saw their detail. Now I can see them, and the noticing comes through when I write. I think it’s really important.

TJW: Can you list five people living or dead who inspire you and why?

EN: I’m always bad at answering these kinds of questions on the spot. It changes too much. Here’s who inspires me right now.

Elizabeth Ellen, Insane Clown Posse, Manuel Marrero, my dumb teenage self, Jackie Ess.

Troy James Weaver lives in Wichita, Kansas, with his wife and dogs. His work has appeared in New York Tyrant Magazine, The Nervous Breakdown, Lit Hub, The Fanzine, Hobart, and many others. His books are Witchita Stories, Visions, Marigold, Temporal, and Selected Stories.

More Interviews