“We’re going to win Sunday. I guarantee it.”

—Joe Namath

by Ryan Ridge and Mel Bosworth

1.

THE SUNDAY WE FISHED THE CANAL

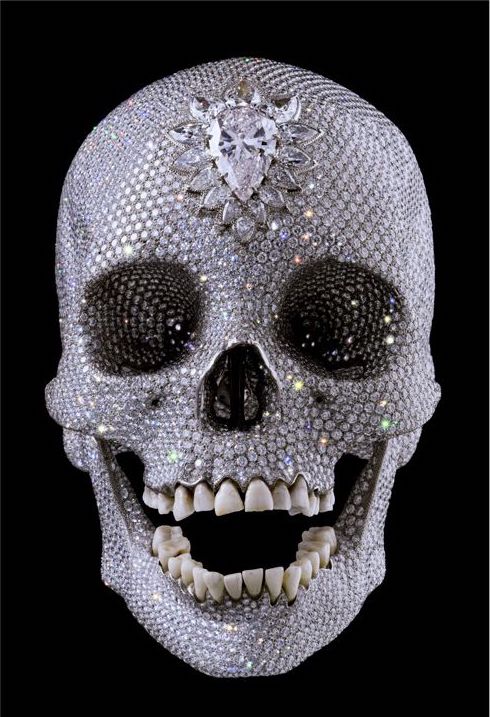

We set up behind the old mill with two lawn chairs and a jug of my experimental moonshine that I’d nicknamed Robert Ford. A single shot could take down Jesse James. Steam rose from the broken concrete as the sun burned off the moisture and warmed the backs of our necks. My neighbor, Ned, dropped his line and set his pole against the railing so he could roll a cigarette. Not a second later the line was racing out and his pole threatened to go over. He tossed aside his smoke and said, “I’ve got something here.” I sipped some outlaw juice and said, “Get it.” And he got it. He reeled it in and said, “Uh-oh.” I took a small boost from the bottle and as soon as I saw what Ned had on the line the moonshine shot through my nostrils and onto my shirt. “Oh shit,” I said, “is that human?” Ned unhooked the skull from the line and said, “It’s covered in diamonds. And these teeth! Look at them. They’re whiter than West Virginia.” I didn’t know what to say so I didn’t say anything. Instead, I watched Ned set his pole against the railing while he stowed the diamond skull in the Styrofoam cooler. Not a second later the line was racing out and his pole threatened to go over. He closed the cooler and said, “I’ve got something again.” I sipped some outlaw juice and said, “Get it, again.” And he got it. This time he reeled in a man in a wetsuit with a scuba mask. I said, “Is that a person?” The man removed his mask and unhooked the hook from his cheek and said, “I’m not just any person. I’m Damien Hurst. I’m an artist. I seem to have misplaced some of my art.” “And what does this art look like?” asked Ned. “Well,” Damien said, “it’s a platinum cast of an 18th-century human skull encrusted with almost 9,000 high-end diamonds, prominently featuring a pear-shaped, pink stone located in the center of the forehead. It’s an extravagant reminder of our own mortality.” Ned said, “Sure, a memento mori. How much is it worth?” Damien thought about it, said, “It’d fetch 50 million pounds, or about 100 million dollars at auction.” Ned laughed and I laughed, too. Just then, the cooler exploded into a million Styrofoam bits and the diamond skull was laughing, too. “There’s nothing funny about art,” Damien said, but we weren’t listening. We were too busy laughing, laughing ourselves to death.

![]()

2.

HOLLOW EARTH SUNDAY

“Come on,” you said. We took the ladder down into the hollow earth. There was a second sun down there that never set. There was an evil legion of retired CEOs sunbathing naked—except for their evil cock rings—on a beach of dinosaur skulls. There was a zombie circus, and all the animals were zombies, too: zombie elephants, zombie zebras, zombie unicorns. The carnival barker was the ghost of Walt Whitman. “Come one, come all!” he said. “Come sing the body electric and the dead body electric! We have electrified zombies on tightropes!” There was a city of smoke with great, quivering high-rises that tickled the underbellies of airplanes, and there was a town of glass where neighbors spent their days naked doing what they normally would—cooking, cleaning, making love—because there was nothing left to hide. Through it all were long and winding streets of ebony. We stopped at the food cart of a vendor who had thick arms and kind eyes. I stuffed my cheeks with chocolate covered pretzels. You winked at me over your fried dough. Just up the street, an argument broke out between two motorcycle mutants. Then a fight broke out. They ripped at each other with chainsaws. The vendor rolled his fingers into fists and took a step toward the melee. Then he stopped and looked back over his shoulder. “You two better go back the way you came,” he said. “It can get pretty wild down here.” We backtracked through the town of glass, stopping for a moment to fog a window with our breath. With our index fingers we rubbed in our initials. A puppy on the other side lazily lapped at our markings. In the city of smoke, we passed swirling versions of ourselves who seemed to smile beneath dark and pluming haircuts. At the circus, the ghost of Walt Whitman floated through our bodies and haunted our hearts with poetry. On the beach of skulls, the CEOs had rolled over onto their stomachs and were snoring loudly. The sun, high and powerful, punished their skin as they slept. We climbed the ladder to the surface, to our bedroom. We sat on the top bunk, smoked a joint, and listened to Dark Side of the Moon. I fell asleep while you braided my hair. I enjoyed that the most. I think I miss that the most. How good you were to me.

![]()

3.

THE SUNDAY WE LEARNED OUR LESSON ABOUT DEMOCRACY

The bus broke down on a lonely stretch in Kansas. The driver stood up and assured us that everything was going to be all right. “Everything is going to be all right,” he said. But after an hour of sitting in the same spot on the same sad highway with the insane storm clouds congregating in the distance and the increasingly irate passengers all sulking and sweating from the humid afternoon air, hey, it was clear that nothing was all right. But, then our savior appeared in an unlikely form when this really dirty guy wandered out of a nearby cornfield and introduced himself. “Hello,” he said, standing at the front of the bus. For some reason, he was holding a propane torch. “My name’s Squeaky. Squeaky Clean. But you citizens can call me Mr. Clean.” He offered to help. He said he was a mechanic. The woman with the faux-hawk in the seat in front of me pointed at the man’s white outfit and said, “That’s a cool costume. Are you some sort of karate instructor?” “No, no.” Mr. Clean said. “I don’t know karate, but I do know crazy. Like I said: I’m a maniac.” “I thought you said you’re a mechanic,” faux-hawk said. “Look, lady,” Mr. Clean said, “I like the fact that you don’t look like a lady or act like a lady. I respect that. I do. But you need to dial it down. You’re at a ten right now and you need to take it to a two. It’s my turn for questions. First question: Do y’all want to live or die?” He gave his propane torch some gas and let a little fire fly. “Let’s take a vote,” he said. “Show of hands. Who wants to live?” I raised my hand along with the bus driver and a couple others. “Okay,” he said, nodding and counting. “Four of you. Now who wants to die?” No one raised a hand. “Hmmnn,” he said. “All be damned! This is like a real election. Only a handful bothered to vote. I tell you what. An observation from a maniac: It isn’t drugs and isn’t poverty. It’s apathy that’s killing this country.” “I thought you said you’re a mechanic,” the woman with the faux-hawk said again. “Lady,” he said, and made a twisting motion with his free hand to silence her. “I’m a mechanic. I’m a maniac. I’m a maniac mechanic!” “That makes you a mechaniac,” she said. “That doesn’t make any sense,” he said. “Come on, let’s do another vote. You folks want my help or not? Show of hands.” Everyone showed their hands. Mr. Clean showed us a pistol and said, “Driver? You mind popping the hood and accompanying me yonder?” The two men left and thunder arrived on cue. Lightning a second later. Rain. A few minutes after that, Mr. Clean and the driver returned wet. “See if it starts,” Mr. Clean said. The driver put the key in the ignition and it started right away. Mr. Clean put the pistol to the driver’s head and told him to go. “Let’s go,” he said. “Where are we going?” the driver asked. “I don’t know. Let’s put that to the people,” Mr. Clean said. “That’s where democracy lies. What do you think, people? Should we head west or south? Show of hands.” The hands showed south and away we went—straight into the storm. And soon enough we weren’t in Kansas anymore. And soon enough we got what we voted for.

![]()

4.

THE SUNDAY HE PAID TO WATCH A MURDER ON THE DARKNET

He’d seen it all or so it felt. He felt bored to death, so he paid to watch one live on the darknet. He transferred the crypto and waited for the webcam to start, but before it started there was a knock at the door. “Who is it?” he asked. “It’s Stephanie,” came the reply. An old girlfriend. He let her in, handed her a beer. They sat beneath a too-honest light at the kitchen table and he asked what brought her to his door tonight. She had nothing but bad news about old friends they’d shared who were either dead from drugs or who were dying from drugs or cancer. About a baby they’d had that he’d never met that drowned in a hotel pool. About our country. Our poor country. They had sad sex right there in the kitchen. He stood behind her at the sink and stared off into the bricked-up window, and then she stood behind him at the sink and stared off into the bricked-up window, each of them reaching a pitiful climax while pressing plastic sporks to their own throats, then she left. He went back to the room, shut the door, shut off the lights, and huddled up with his laptop on the bed. The webcam was live. A death was well underway. Torture. Real slow. Young kids all—killers and soon to be killed. Awful stuff. He tented a blanket over himself and the laptop. His stomach soured. The back of his head grew heavy with murk. He wanted this bad feeling all for himself. He got what he wanted. Monday morning—if it came—would offer different flavored monsters.

![]()

5.

THE SUNDAY THE FIREHOUSE BURNED DOWN

The captain stubbed out his cigarette in my oatmeal. He said, “What do you think of that, chickenshit?” I frowned. He was referring to an incident during a recent run where I’d puked and almost passed out after seeing a teenager’s decapitated head on the dashboard during a Jaws of Life extrication. The thing that spooked me was her eyes. They were wide-open and she had these bright green irises which were illuminated in short bursts by a combination of the cold moonlight in conjunction with the rotating LED lights from the police cruisers behind us—and we had to pry apart the passenger door and pull the drunk driver out from the sunroof on account of the other side of the Honda Accord was an accordion and somehow this dude was drunk enough and loose enough to live and so we yanked him over his girlfriend’s headless torso and out of the car and then the paramedics hoisted the bastard into the ambulance which screamed instantly into the night and the entire time the girl’s green eyes stared me down from the dash and that’s when I keeled over in the emergency lane and lost the pancakes I’d had for dinner on the side of the road. I wiped my mouth and steadied myself against the guardrail. The captain appeared, patted me on the arm, and said: “Get it together, chickenshit. Do your damn job.” I did my best, but the rest of the night I kept picturing her eyes, unflinching, and her long, thin neck leading to nowhere and even now, days later, staring dumbly at my breakfast-turned-ashtray, pondering the fragility of the entire endeavor and worrying about the randomness of everything and the genuine possibility that none of it really matters, I stood up and poked the captain hard beneath his badge and said, “I’ll tell you what I think about that. I’ll do you one better and tell you what I think about everything. I think: burn it all down, motherfucker. Torch it.” I walked out and didn’t look back. That night, I started a fire in my fireplace and then I decided to set my house on fire. For an encore, I set the neighborhood on fire. Then I drove over to the firehouse and set it on fire, too. I was in the firehouse when the firehouse burned down. I slid down the pole as the flames rose up to greet me.

![]()

6.

SUPERSTAR SUNDAY

Around midnight I stumbled to the club and stood in line in my best suit. Once inside, I ordered a coffee and the bartender ordered me to pipe down now. After three coffees he cut me off, but I didn’t cut the bastard any slack. I said, “Look, man, I’m a coffee man. I like my coffee hot, and I like my coffee when I want it. And I want my coffee, man, you understand?” The bartender pointed to the door with his chin because he had a huge chin. You could fit at least five cups of coffee on that chin. “Shove off,” he said. “It’s high time for pie time. There’s a slick pie bar around the corner. Find yourself a seat. Find yourself a treat. I recommend the pie.” I slammed my palms on the bar. “I don’t want pie, although that sounds pretty good right now. They got coffee over there, too?” Suddenly I lost my wind because my windpipe was cut off by my shirt. There was something big and strong behind me, and it was twisting my shirt at the back of my neck. Next thing I knew I was floating toward the door. “Byeeee!” said the bartender, but I couldn’t talk back. Bastard! Then I was on the street, then the sidewalk, then at the pie bar around the corner. The place smelled like a giant key lime pie and everywhere I looked was a window. It must’ve been dawn because black night was cupped in deep purple with lacy pink light. “Give me some pie!” I shouted. “And a black coffee!” They brought me what I asked for and I said to the waitress, “You’re a star!” and she said, “No, you’re a star!” Then the big star of our solar system made its grand appearance and the windows glowed and swelled. Photons shot like arrows through every part of me and my heart fell open like a good book.

![]()

7.

THE SUNDAY THE SNOW FELL BACK INTO THE SKY

We were buried beneath two feet of the white stuff. I was on my sixth beer and my second marriage. We were still in our honeymoon phase. Bridget went to grab another board game when something caught my eye through the picture window. It was a sicko in a ski mask. I closed the curtains, but the pervert knocked on the window anyway. I poked my head through the curtains and told him to go to the door. The doorbell rang. Bridget said, “I’ll get it.” I said, “Don’t answer it.” But it was already too late. The pervert was standing in our foyer now. He removed his ski mask. It was our neighbor Ned. Ned said, “You’ve got to get out here and see this. Something’s happening. Something strange.” We followed Ned into the yard and sure enough it was weird. The snow from the ground had somehow reversed course and now fell backwards into the sky. For a few moments, we stood there like dominos before we also fell upwards into the clouds. Drifting away from the earth, I watched my neighborhood disappear. I waved goodbye to my town, my country, my life. I felt a sudden surge of nostalgia and a little lightning in my heart—a warmth despite the intensely cold air. Gone altogether were my myriad anxieties and my extended list of regrets. Gone, too, were Bridget and Ned. It was just me and the half-full can of High Life in my hand. I took a sip and I choked and coughed and coughed and choked, saw stars. Then there was light in my eyes and light all around. Beyond that, mystery. Pure mystery. And for once, I felt fine.