I Wake Up Streaming: August 2021

Movies

In this edition of “I Wake Up Streaming,” novelist William Boyle rounds up his top streaming picks for the month of August. The column’s name is a play on the 1941 film I Wake Up Screaming, starring Betty Grable, Victor Mature, and Carole Landis. While the film’s title hits a pleasing note of terror and despair, changing that one letter speaks to the joy of discovering new films and rediscovering old favorites, as well as the panic that comes with being overwhelmed by options.

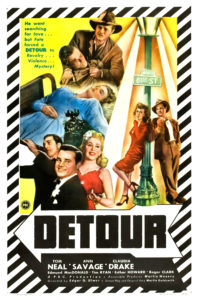

Detour (1945) (Criterion Channel, Kanopy, Paramount Plus, Tubi, Prime Video, YouTube)

I was twelve years old in 1990 when I saw Edgar G. Ulmer’s Detour on television. It played on PBS, one of only seven stations we got; its grittiness and its stripped-down, relentless desperation drew me in. I didn’t know who Ulmer was. I liked old movies and books. My tastes ran dark. But this, this was something else, something old that felt new and dangerous. It was a knife thrust of a movie, anchored by Ann Savage’s supporting turn as Vera, “a role as much ferally attacked as performed,” to borrow a phrase from director Guy Maddin.

I was twelve years old in 1990 when I saw Edgar G. Ulmer’s Detour on television. It played on PBS, one of only seven stations we got; its grittiness and its stripped-down, relentless desperation drew me in. I didn’t know who Ulmer was. I liked old movies and books. My tastes ran dark. But this, this was something else, something old that felt new and dangerous. It was a knife thrust of a movie, anchored by Ann Savage’s supporting turn as Vera, “a role as much ferally attacked as performed,” to borrow a phrase from director Guy Maddin.

This past weekend, I talked to the great Walter Chaw for his Denver Public Library Saturday Matinee series. When Walter invited me to be a guest, he said I could pick whatever film I wanted to discuss (the only restriction being that it should preferably be available on library streaming service Kanopy). I didn’t hesitate at all before I chose Detour, the film that switched my brain and established so many of my obsessions: narrative detours, unreliability, identity, coincidence, lack of polish, studies of people on the margins, doom. Detour was a gateway drug to noir for me, one that I’ve returned to often over the years and still return to. I was beyond thrilled when Janus/Criterion put out a stunning restoration a couple of years back. Even though the film looks better than it’s ever looked, I still marvel at the eternal rawness of it. In preparation for my conversation with Walter, I revisited Martin M. Goldsmith’s source novel, as well as Noah Isenberg’s excellent BFI Classics book on Detour and his biography of Ulmer. I also rewatched the film several times. Writing about it here is an act of utter selfishness—my mind has been preoccupied with all things Ulmer and Detour-related these last several weeks, so it would’ve been a challenge to discuss many other films.

Detour is knotty and difficult. On the surface, it’s a sort of elemental noir. Ulmer had a small budget and shot the film for his Poverty Row studio in two weeks (or possibly less). The runtime is sixty-seven minutes. It’s a road movie, but it’s never really on the road. Rear projection dominates. Artificial fog covers up for the lack of sets. This all leads to a haunted, claustrophobic quality. Other than cars rattling through a projected desert, we’re mostly in dive spaces: diners, motels, shabby apartments. Tom Neal plays Al Roberts, a classically trained pianist who has been working in jazz clubs and is now thumbing rides across the country from New York to Los Angeles, hoping to get back to his girlfriend, Sue Harvey, who skipped town with the dream of making it big in Hollywood. Things don’t go well for Al. He gets a ride from a big spender named Haskell, who’s carrying around his own troubled past. Call it coincidence or fate, but Al winds up in a corner when Haskell croaks. Figuring people will think he killed Haskell, Al assumes the stranger’s identity. Making off with Haskell’s car, he decides against his better judgment to give a ride to a hitchhiker he meets further on up the road. This is Ann Savage’s Vera—who, as Noah Isenberg writes, puts the picture in a headlock from the moment she enters it—and she’s got her own history with Haskell.

Since reading Isenberg’s Ulmer bio for the first time about six or seven years ago, Ulmer has become an artistic hero of mine. He was able to do so much with so little, to make magic out of dust and dirt and shadows. He was on fire with creativity. Andre Gidé famously said that “art is born of constraint and dies of freedom,” and Detour—a small miracle of a movie, a gift from the gutter—is proof that’s true.

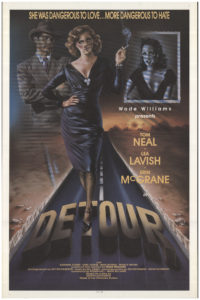

Detour (1992) (YouTube)

Given my deep dive on Ulmer’s Detour, I also rewatched Wade Williams’s little-known 1992 remake. Most notably, it adheres to Martin Goldsmith’s original script and his novel (Ulmer had to excise some of the story because of time and budgetary constraints). Detour ’92 isn’t conventionally great or even very good, but it’s beyond fascinating as an artifact of cinematic devotion and obsession. Williams seems to want to get utterly lost in the grimy world of the original. But an early-’90s low-budget movie with a cast of C actors—as Walter Chaw observed in our talk—winds up feeling more like a sad porno without any skin. I’d still take this sincere amateurish cheapie over most remakes or reboots. Tom Neal, Jr. lacks real enthusiasm, but he’s a dead ringer for his old man (with maybe a dash of Audie Murphy mixed in there). Though no one could ever live up to Ann Savage, Lea Lavish makes for a pretty solid (and haunting) Vera—kind of a soap opera riff on Savage’s wrecking ball of a performance, an act of devout mimicry. I like the attempts to bring back Sue Harvey’s Hollywood thread, something totally cut from Ulmer’s version. I also like that they stuck with the original ending (the Production Code forced the very last moment on Detour ’45). Vibe-wise, it has a lot in common with Maggie Greenwald’s 1990 Jim Thompson adaptation, The Kill-Off. Well worth watching. Definitely feels true to the spirit of the original. Raw (if not revelatory), earnest, crummy, melancholy, and weird. It’s like an ambitious community theater production of Detour (I mean that in the best possible way). “Who wants to live like real people?” Sue Harvey asks her jilted cowboy actor boyfriend late in the film. Who indeed?

Given my deep dive on Ulmer’s Detour, I also rewatched Wade Williams’s little-known 1992 remake. Most notably, it adheres to Martin Goldsmith’s original script and his novel (Ulmer had to excise some of the story because of time and budgetary constraints). Detour ’92 isn’t conventionally great or even very good, but it’s beyond fascinating as an artifact of cinematic devotion and obsession. Williams seems to want to get utterly lost in the grimy world of the original. But an early-’90s low-budget movie with a cast of C actors—as Walter Chaw observed in our talk—winds up feeling more like a sad porno without any skin. I’d still take this sincere amateurish cheapie over most remakes or reboots. Tom Neal, Jr. lacks real enthusiasm, but he’s a dead ringer for his old man (with maybe a dash of Audie Murphy mixed in there). Though no one could ever live up to Ann Savage, Lea Lavish makes for a pretty solid (and haunting) Vera—kind of a soap opera riff on Savage’s wrecking ball of a performance, an act of devout mimicry. I like the attempts to bring back Sue Harvey’s Hollywood thread, something totally cut from Ulmer’s version. I also like that they stuck with the original ending (the Production Code forced the very last moment on Detour ’45). Vibe-wise, it has a lot in common with Maggie Greenwald’s 1990 Jim Thompson adaptation, The Kill-Off. Well worth watching. Definitely feels true to the spirit of the original. Raw (if not revelatory), earnest, crummy, melancholy, and weird. It’s like an ambitious community theater production of Detour (I mean that in the best possible way). “Who wants to live like real people?” Sue Harvey asks her jilted cowboy actor boyfriend late in the film. Who indeed?

Heat Lightning (1934) (Watch TCM)

Sticking with the theme of detours, this pre-Code gem from Mervyn LeRoy is one of my favorite film discoveries of the year. Olga (Aline MacMahon) and Myra (Ann Dvorak) are sisters who run a desert gas station. Trouble comes in the form of a couple of fugitives who have just botched a bank heist and are on the lam. As if that weren’t bad enough, Olga—having run away from a life she wants to leave in the past—has a history with one of the crooks. LeRoy shot Heat Lightning on location in the Mojave Desert and—despite its one setting—manages to make it feel big and open but also trapped in a cage. Some shots through the gas station windows are simply stunning, figures unspooling darkly against the vast landscape. Though there’s a play-like quality to the proceedings, it never feels stagey. At an economical sixty-three minutes, LeRoy lets MacMahon’s face reveal her backstory without getting lost in the weeds. She’s brilliant as Olga, haunted and mesmeric and vulnerable. Heat Lightning is ambitious, unorthodox, subversive, slangy, and electric. I can’t believe I’d never seen this masterpiece until now.

Sticking with the theme of detours, this pre-Code gem from Mervyn LeRoy is one of my favorite film discoveries of the year. Olga (Aline MacMahon) and Myra (Ann Dvorak) are sisters who run a desert gas station. Trouble comes in the form of a couple of fugitives who have just botched a bank heist and are on the lam. As if that weren’t bad enough, Olga—having run away from a life she wants to leave in the past—has a history with one of the crooks. LeRoy shot Heat Lightning on location in the Mojave Desert and—despite its one setting—manages to make it feel big and open but also trapped in a cage. Some shots through the gas station windows are simply stunning, figures unspooling darkly against the vast landscape. Though there’s a play-like quality to the proceedings, it never feels stagey. At an economical sixty-three minutes, LeRoy lets MacMahon’s face reveal her backstory without getting lost in the weeds. She’s brilliant as Olga, haunted and mesmeric and vulnerable. Heat Lightning is ambitious, unorthodox, subversive, slangy, and electric. I can’t believe I’d never seen this masterpiece until now.

Carnival of Souls (1962) (Criterion Channel, Kanopy, Shudder, Tubi, HBO Max)

A tweet from Walter Chaw comparing Ulmer’s Detour to Herk Harvey’s disorienting and terrifying Carnival of Souls sent me back to the film for the first time in many years. In fact, it does have plenty in common with Detour. Both are relentless, desperate, and purgatorial. It was also shot on an ultra low budget and traffics in narrative detours. Candace Hilligoss plays Mary Henry, who—at the start of the film—is in a car with two friends in Kansas. Another car, this one full of boys, pulls up next to them, and Mary’s friend agrees to a race. The race takes them over a bridge, and the driver of Mary’s car loses control. They plummet into the murky river below. Mary emerges some time later, the sole survivor. Attempting to leave the tragedy behind her, she takes a job as a church organist in Utah. Meanwhile, visions of a pale man plague her. She moves into a rooming house and is drawn to a deserted carnival on the edge of town, which seems to hold some answer she’s looking for. It’s all very unnerving and shot through with nightmarish elegance.

A tweet from Walter Chaw comparing Ulmer’s Detour to Herk Harvey’s disorienting and terrifying Carnival of Souls sent me back to the film for the first time in many years. In fact, it does have plenty in common with Detour. Both are relentless, desperate, and purgatorial. It was also shot on an ultra low budget and traffics in narrative detours. Candace Hilligoss plays Mary Henry, who—at the start of the film—is in a car with two friends in Kansas. Another car, this one full of boys, pulls up next to them, and Mary’s friend agrees to a race. The race takes them over a bridge, and the driver of Mary’s car loses control. They plummet into the murky river below. Mary emerges some time later, the sole survivor. Attempting to leave the tragedy behind her, she takes a job as a church organist in Utah. Meanwhile, visions of a pale man plague her. She moves into a rooming house and is drawn to a deserted carnival on the edge of town, which seems to hold some answer she’s looking for. It’s all very unnerving and shot through with nightmarish elegance.

Seven Men from Now (1956) (Criterion Channel)

In the late 1950s, director Budd Boetticher and star Randolph Scott teamed up for a string of westerns referred to as the Ranown cycle after Scott’s production company. The great Burt Kennedy wrote all but two. You can’t miss with the Ranown Westerns collection that’s just gone live on the Criterion Channel—all six films are excellent—but Seven Men from Now, the team’s first collaboration, remains my favorite. (It’s also been the most difficult of the bunch to see for some time.) Scott plays lawman Ben Stride, who is on the hunt for the seven rogues who murdered his wife in the process of robbing a Wells Fargo freight station. While tracking the killers, Stride encounters a pioneer couple from the east on their way to California (played by Walter Reed and Gail Russell), as well as his old nemesis, Masters (a sweaty, villainous turn by the legendary Lee Marvin early in his career). At seventy-eight minutes, Seven Men from Now is lean, muscled up, and rife with tension. The film was shot in WarnerColor, often called “a poor man’s Technicolor,” but it’s gorgeous to look at, bright and brilliant, with lush cinematography from William H. Clothier.

In the late 1950s, director Budd Boetticher and star Randolph Scott teamed up for a string of westerns referred to as the Ranown cycle after Scott’s production company. The great Burt Kennedy wrote all but two. You can’t miss with the Ranown Westerns collection that’s just gone live on the Criterion Channel—all six films are excellent—but Seven Men from Now, the team’s first collaboration, remains my favorite. (It’s also been the most difficult of the bunch to see for some time.) Scott plays lawman Ben Stride, who is on the hunt for the seven rogues who murdered his wife in the process of robbing a Wells Fargo freight station. While tracking the killers, Stride encounters a pioneer couple from the east on their way to California (played by Walter Reed and Gail Russell), as well as his old nemesis, Masters (a sweaty, villainous turn by the legendary Lee Marvin early in his career). At seventy-eight minutes, Seven Men from Now is lean, muscled up, and rife with tension. The film was shot in WarnerColor, often called “a poor man’s Technicolor,” but it’s gorgeous to look at, bright and brilliant, with lush cinematography from William H. Clothier.

The Lady in Red (1979) (Tubi)

Somehow my first time watching Lewis Teague’s The Lady in Red. A knockout John Sayles script. Subversive, political, smart as hell, streamlined, brutal. Has the genuine feel of an early-’30s pre-Code gangster movie mixed with scuzzy ’70s exploitation fare. Incredible pacing—at war with bloat. Pamela Sue Martin is terrific as Polly Franklin, the farm girl turned prostitute who went on to become John Dillinger’s girlfriend. Great supporting turns by Louise Fletcher (her “coins in my mouth” speech is the best scene in the movie), Robert Forster, Robert Conrad, and an eerie Christopher Lloyd as the terrifying mobster Frognose. It’s pretty wild and perfect, if you ask me. Not sure how I missed this one for so long. Just got a Blu-ray from Shout! Factory (on a Corman double bill with Jonathan Demme’s Crazy Mama), and it’s also available on Tubi.

Somehow my first time watching Lewis Teague’s The Lady in Red. A knockout John Sayles script. Subversive, political, smart as hell, streamlined, brutal. Has the genuine feel of an early-’30s pre-Code gangster movie mixed with scuzzy ’70s exploitation fare. Incredible pacing—at war with bloat. Pamela Sue Martin is terrific as Polly Franklin, the farm girl turned prostitute who went on to become John Dillinger’s girlfriend. Great supporting turns by Louise Fletcher (her “coins in my mouth” speech is the best scene in the movie), Robert Forster, Robert Conrad, and an eerie Christopher Lloyd as the terrifying mobster Frognose. It’s pretty wild and perfect, if you ask me. Not sure how I missed this one for so long. Just got a Blu-ray from Shout! Factory (on a Corman double bill with Jonathan Demme’s Crazy Mama), and it’s also available on Tubi.

William Boyle is the author of the novels Gravesend, The Lonely Witness, A Friend Is a Gift You Give Yourself, and City of Margins, and a story collection, Death Don’t Have No Mercy. His novella Everything Is Broken was published in Southwest Review Volume 104, numbers 1–4. His writing on film has appeared in Oxford American and CrimeReads. He used to have a blog about ’70s crime films called Goodbye Like a Bullet. His website is williammichaelboyle.com.

More Movies