I Wake Up Streaming: February 2022

Movies

In this edition of “I Wake Up Streaming,” novelist William Boyle writes about one of his all-time favorite films that is now available streaming for the first time. The column’s name is a play on the 1941 film I Wake Up Screaming, starring Betty Grable, Victor Mature, and Carole Landis. While the film’s title hits a pleasing note of terror and despair, changing that one letter speaks to the joy of discovering new films and rediscovering old favorites, as well as the panic that comes with being overwhelmed by options.

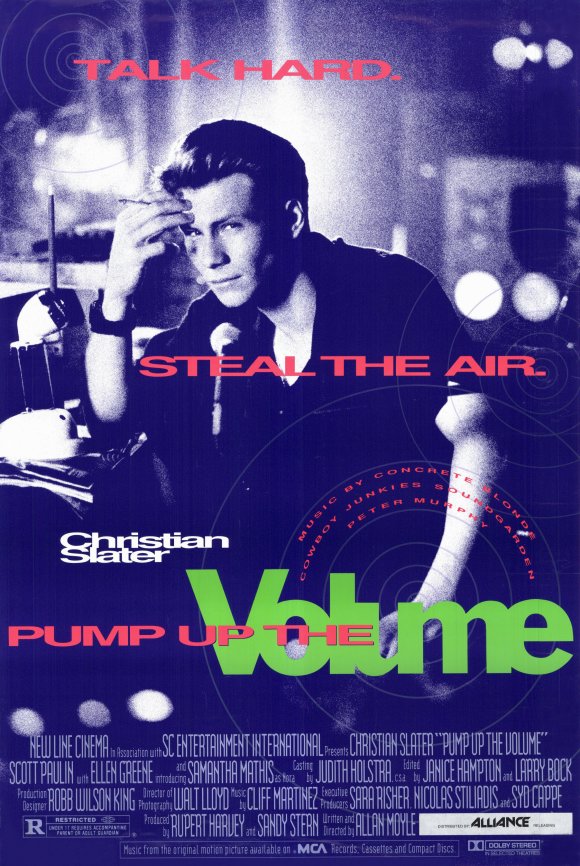

Pump Up the Volume (HBO Max)

I was in seventh grade when I first saw Allan Moyle’s Pump Up the Volume. I went to a Catholic school in southern Brooklyn called St. Mary’s. We’d get out early on Wednesdays, around noon. Kids would linger in the schoolyard or duck into bodegas for Swedish Fish and quarter waters. There would be games of Kill-the-Man-with-the-Ball in Shady Park or the P.S. 101 parking lot. Part of my tradition—whenever I eventually headed back to my grandparents’ house—was stopping at my neighborhood video store. The place didn’t have a name—I mean, it did, but it was something bland like International Video. The guy who owned it was Russian and had the hairiest hands. Hair just seemed to be flowing from his sleeves all the way over his knuckles. Maybe it was exactly like that, but maybe I’m remembering wrong. Either way, I called him Wolfman. I was a regular in that joint, usually renting three tapes for the price of two from the non-new release section, unless there was something I really wanted to see that had just come out. Between Gleaming the Cube and Heathers, I was already a big Christian Slater fan, so I rented Pump Up the Volume when I saw the box sitting there next to the register. Wolfman didn’t have a reaction one way or the other, no matter what anybody rented. He was never impressed and never disgusted, not with the normal renters anyway. He did, however, look with disdain on the old men who pushed through the saloon doors into the porno room and came out with big plastic cases.

Pump Up the Volume had been released in theaters in August 1990 and had been on my radar because I’d read a positive review in the Daily News. This must’ve been early 1991 when it was released on VHS. I took it back to my grandparents’ house, where I stayed until my mom got home from work around six or seven. They had a VCR, a workhorse top-loader, and that’s where I watched many of my movies. I inserted the tape. My grandfather was in the basement working on a TV. My grandmother was in the kitchen, playing solitaire and drinking instant coffee. They usually left me alone while I watched movies.

I was sucked in immediately to Moyle’s tale of an outcast trying to make sense of the world. Slater’s Mark Hunter is a transplant to suburban Arizona. By day, he’s a shy high school student, a loner, smart but reserved. At night, he broadcasts an anonymous pirate radio show from his parents’ basement, using the name Happy Harry Hard-on. Fellow student Nora Diniro, played by Samantha Mathis, sends letters to his private mailbox, and tries to find him out. Others from the high school call in with their problems. Tapes of his show get bootlegged and passed around. The administration rebels. Mark is backed into a corner and must act. I identified with him—he was quiet in real life but could say things on his show. I was quiet too, but I loved to write, and I could really say things on the page that I could never say in real life. I was also in love with Samantha Mathis’s Nora; she played the part with such coolness and vulnerability.

My grandmother must’ve heard something in the movie she didn’t like because she came in and sat down and watched on the recliner for a bit, her elbows on her knees, a look of disgust on her face. She was a sweet woman, the best, but that day I didn’t like her. She told me to shut the movie off. I did. I figured I’d watch it on the sly somehow, which seemed appropriate given the subject matter.

My mother and I had a VCR in our apartment too, and I managed to watch the movie about four times before returning it to Wolfman’s. After that, I developed a plan. If I could get our VCR and my grandparents’ VCR together, I could dub the movie. I’d done it a few times before.

The plan came off without a hitch. The trick was bringing my grandparents’ VCR to our apartment because it was my grandmother who’d taken offense to the movie. My mother didn’t like movies, but, to her great credit, she never tried to stop me from watching anything. Pump Up the Volume felt dangerous because I was seeing a movie that felt true, not because anyone was trying to censor or control what I watched or didn’t watch. I bought a blank Maxell tape at the drugstore up the block, rented Pump Up the Volume again, and dubbed it on SP so the quality was better.

I’ve never watched a movie as much as I watched Pump Up the Volume, and I never will come close. The numbers are astounding. I engaged with it in a way that’s particular to youth. It became part of my routine. I watched it almost daily for years. We’re talking maybe four or five times a week from seventh to tenth grade. It carried me from junior high into high school. Usually, when someone says they’ve watched a movie thousands of times, it’s an exaggeration. Maybe, if someone really loves a movie and shows it to all their friends, they see it fifty times or a hundred. That would be a ton. Pump Up the Volume was more than a comfort movie to me. I used it to combat my loneliness, sure, but it was—and remains—a text that helped the world make sense to me. It became as necessary as breathing.

Part of that sense derived from the soundtrack. It was a life changer, another overused term, but true in this case. Through the movie, I first heard Leonard Cohen, Camper Van Beethoven, the Pixies, MC5, Soundgarden, Sonic Youth, Concrete Blonde, Cowboy Junkies, and more. I bought the cassette at Sam Goody at the mall and wore out my Walkman listening to it. It represented a seismic shift in my music taste. (Before that, I’d mostly listened to hair metal bands. Guns N’ Roses, Skid Row, Tesla, and Cinderella were my favorites, but I also made room for Winger, Kix, Slaughter, White Lion, Warrant, and others.) Many new roads developed from my exposure to these artists. Many new ways of seeing and being.

Pump Up the Volume got me through the early part of high school. I watched other movies, of course, but it was one I continued to return to. That dubbed copy (which I still have somewhere) played like a transmission from another planet. The tracking couldn’t be fixed because the tape was tired. As I got older, I watched more and more movies and watched more widely. I didn’t leave Pump Up the Volume behind—I referenced it often, bought Black Jack gum when I could find it, hung on to the soundtrack even after I’d dumped most of my tapes in a garbage can in Bay Ridge when a record store refused to buy them for credit—but I’d watched it enough to last for a long time.

The movie got a DVD release in ’99 but then faded out of circulation. It fell into that peculiar limbo that so many movies have fallen into—I’m guessing it was a music rights thing. But it remained a marker for people of a certain age, late Gen Xers, and if I was ever around folks who knew and loved it, I knew I’d found my crew. A couple of years ago, a bootleg rip of it appeared on Prime Video but was quickly taken down. Last year, Warner Archives finally put it out on Blu-ray, a cause for celebration (even if they digitally scrubbed the cigarette from Slater’s hand on the cover). Now it’s on HBO Max, its first legal appearance on a major streaming service. Hopefully, this means it will find a new audience, and a new generation will connect with its portrayal of despair and healing.

I’ve rewatched Pump Up the Volume a few times during the pandemic, allowing myself to be rescued by it yet again. It’s a work of great empathy. As Walter Chaw notes, it “shines in its exploration of depression and trauma.” It’s simultaneously sad and invigorating to exist in the headspace that I existed in thirty years ago, when I felt lost and alone and was fighting for something to believe in, something to hope toward. The movie’s proven to be prophetic, too. Slater’s character might’ve paved the way for every mook who has a podcast, but don’t make the mistake of thinking that he’s a prototype for a certain kind of white male claiming voicelessness and trying to avenge his loss of status or purpose. Mark has a good heart, and, as Chaw writes, the movie is ultimately “a prayer that we remember what it felt like to take a stand.” Talk hard.

William Boyle is the author of the novels Gravesend, The Lonely Witness, A Friend Is a Gift You Give Yourself, City of Margins, and Shoot the Moonlight Out, all available from Pegasus Crime. His novella Everything Is Broken was published in Southwest Review Volume 104, numbers 1–4. His website is williammichaelboyle.com.

More Movies