McSweeney’s 65 | Ain’t Them Bodies Saints

Web Exclusives

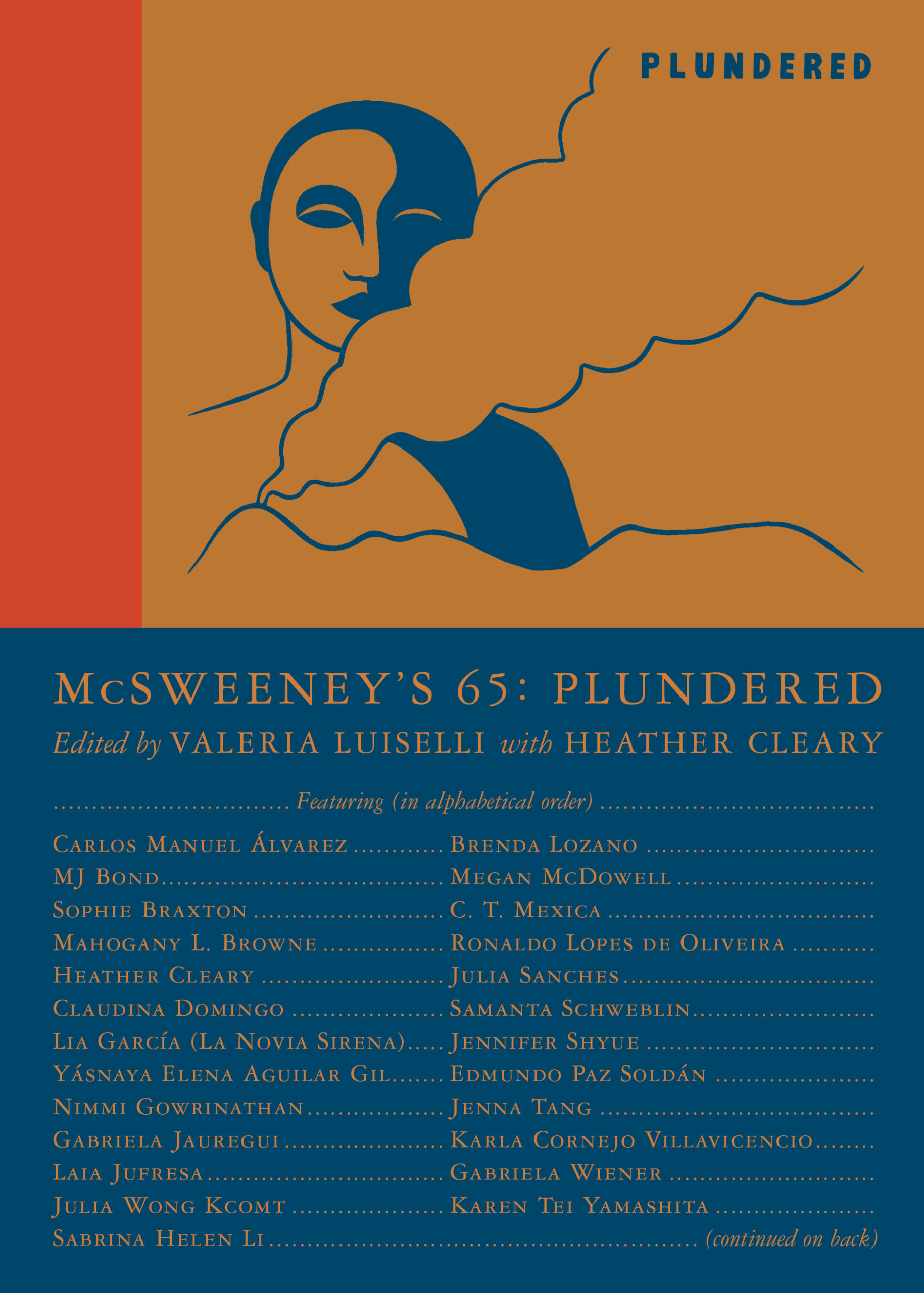

The following story by C. T. Mexica appears in McSweeney’s 65: Plundered, guest-edited by Valeria Luiselli with Heather Cleary. In fifteen bracing stories, the collection spans the American continent, from a bone-strewn Peruvian desert to inland South Texas to the streets of Mexico City, and considers the violence that shaped it. With contributors from Brazil, Cuba, Bolivia, Mexico, Argentina, Ecuador, the United States, and elsewhere, Plundered is a sweeping portrait of a hemisphere on fire.

A child is a lonely thing to put in prison

Without a lover lonely in its parent’s care.

—Olga Broumas, Perpetua

Some vato, in some pinta somewhere, must have unhooped his pedazo and noticed that it looked very much like a chocolate bar, except this Whatchamacallit was hard and hazardous, giving birth to another convict term of art: hard candy. Graveyard humor for the brutal intimacy of a shank reserved for the unwanted of the underworld. And also for enemies both made and inherited. Or for those once considered friends who were now ostracized. Removals and regime change were just part of the ruthless pragmatism of the demimonde. Private codes for a private world.

He had two pedazos in this situation. His captors knew that biology cannot be denied, and he’d eventually have to extract whatever he had hooped. The authorities were hoping the evacuation would produce any pedazo, clavo, or huilas that he’d gangstered up there. That is how he ended up in that dry cell. The toilet in a dry cell is essentially a toilet atop a fish tank, designed to recover any contra- band inserted or ingested. In the private language of the imprisoned, inserting has evolved from keistering to hooping and gangstering.

For hygienic purposes, he had already trained himself to handle his business first thing in the morning. He’d seen men bludgeoned for farting among bona fide convicts. Same goes for those picking their Paris Hiltons. He liked to be light and clean, so he evacuated both his dookshoot and snotlocker way before breakfast was served. All shit, showered, shaved, and shined for the morning slop.

A snitch’s accusation landed him and a few others in dry cells, and, as he was known to always be armed, the staff were waiting for him to evacuate whatever he had. And he would, but by then he had gotten into the habit of carrying two pedazos in his person. He’d give them their treat and keep the other. He still had a few hours to go until dawn, his self-trained routine, so he went about situating himself in that cold, bare cell and ignored the staff member sitting on the other side of the cell’s observation window. As he became institutionalized, he began to appreciate the clarity of an austere cell. It reminded him that his courage must remain constant and that he must never abandon himself. He had long ago come to see punishment as a painful honor for bringing his enemies sorrow.

In those dry cells, he always thought of water, especially the flow of a river beginning in the floating lakes that nourished the rocky peaks of a high wilderness. Like his ancestors, he and his family were always on the move. The ancients followed the weather and were guided by mountains, all the while weaving their humanity into the cosmos of two continents. Over thousands of years, they filled those immense landscapes with vast localisms anchored in their dreamscapes.

His family eventually found a brave and grand river that became the special country of their hearts. His father’s people would find themselves on the upper reaches of the grand river, where plateau cities abounded. His mother’s people would find themselves in the sultry sea plain of the lower reaches of the brave river, where it freed itself from its long journey into a large basin of murky salt water.

Though once it was a brave and grand river that ran free and wild, now it was drowned by the acceleration of newcomers with lustful spirits. The newcomers blocked the river with barricades and boundaries. On the upper reaches, this hastening cultivated mutiny in the hearts of many who were eventually confined on reserves. Later, many of their children would be sent to schools where the dreams of their ancestors were either quieted or extinguished in the name of acceleration. His father told him that those children and all Indigenous children that followed were born prisoners of war. These confinements caused many to die of broken hearts. The lower reaches would be just as contested and would come to have men with guns on both sides, with families seeking relief from the cruelties of its lower bank. These families were halted and separated, and many of the children were put into cages in camps of saints bereft of tender mercies. Some of the unbroken among them would later find themselves in dry cells con sólo la melancolía de ese río.

In time, he came to think of it as a river with two kinds of pain. One was a steady, malevolent pain that felt like an abyss—an energy vampire feeding on an open wound. The other had a bridge that could quiet some of the pain of a journey where the way was long and the roads were bad.

His mother’s gente were from inland South Texas, and he grew up running through that caliche dirt and brush country all the way up to the vaporous waters on the coast. When he was a child, he would listen to his elders talk in low, gentle voices about violent things. “What they did to us,” some would say, “let their god repay.” They talked about obras desalmadas and other evils visited upon their gente and against the land. One of the most recent cycles they called “the Hora de Sangre,” on account of countless attacks and lynchings on real American dirt where periwinkles bloom.

His father’s gente did not fare any better among the chamiso and piñon pine of northern New Mexico. They were last in Arroyo Hondo, home of a failed populist insurrection against another wave of expeditioners, who spoke a florid language that the locals would soon make their own. His father, like he, was state-raised in gladiator schools. The son knew his father mostly through jailhouse letters. His father wrote in a fine longhand that the son emulated and that was once praised by a sweetheart as sinisterly elegant. She said it must have been the way Dracula wrote.

He was a prison baby whose institutionalization began in the maximum-security visiting room where his parents first met. That was his father’s house. Long before he ever set foot in a detention center, he grew up in the prison cultures that the men, and later the women, brought home. When he was just a child, he could already hear tractors paving new routes to new prisons. Small-walled villages where criminal children came of age. Places where dreams were extracted and extinguished while childhood hid its departure from them. Places for good boys who did some awful things to bad people and bad boys who did awful things to one another. Boys who couldn’t always hold the dark and came up in cells that gave their pain the dignity of privacy. The things many of them felt, they would rather have felt alone. Because much of life hurt, their fun included a lot of hurting. For every joy there were a hundred pains.

At the first detention center he was sent to, the juveniles were lined up in front of their cells before getting locked in for the night. This was the nightly ritual in which they removed their elastic-waisted tramos and canvas kicks and placed them outside their cell doors. The Bob Barkers were color-coded by waist size: green for the pip-squeaks, blue for the moderately inclined, and khaki for waves of confidence. The slip-on shoes were called winos by the boys with oblique eyes and high cheekbones. The boys with skin that don’t crack called them croaker sacks. Some were there only in passing. Those were the juvenile delinquents. A smaller group was becoming impervious to the deprivations of incarceration. They were training themselves to endure hardships without complaint. Those were the true believers, who earnestly began their criminal apprenticeships. Children of adversity whose paper trails led to the joint, the criminal children who never intended to know any life other than that of banditry. They would grow up taking pictures in prison yards where they archived albums of outlawry. Those were the young convicts—a term of honor distinct from inmate. They inherited the convict code and adapted it for their generational circumstances, then passed it on to the next wave of true believers. No matter the variations, it would always be based on three prohibitions: no snitches, no rapos, and no chesters. Wherever bona fide convicts are warehoused, they will not program with those undesirables. Puros vatos felones who were honor-bound to create brave spaces for themselves wherever they landed.

His age group was the inaugural generation of mass incarceration. Their class years ranged from the late ’80s to the early ’90s. Some of them would skip grades and go straight into institutions of higher punishment. But first there were the gladiator schools. No graduation robes, just jumpsuits of varying colors. When he was seventeen, his high school diploma was unceremoniously slid under his solitary cell door, and he placed it on top of a neat stack of official paperwork until it disappeared in one of many cell searches. Ni modo. It be’s that way sometimes, bro. The peer reviews he valued came from righteous convicts who let others know of his stellar underworld credentials. His reputation got to each facility long before he did.

When he was first sent to the institutions, he quickly learned that incarceration is more about what you have to become than what you want to be. That becoming was the emotional numbness on the face of an expressionless convict. It was unbecoming of the song his mother put into his heart. It was a gaze that prepared him for the tragedies to come. A resting face fed by prison’s slow drip of adrenaline. He did it because he had to, then because he liked it and became good at it, and one day he came to believe he was meant for it.

What he had wasn’t new. He first sensed it in the older men he grew up around. The men in his family were only unquestionably together in prison and in war. It was only in violence that they were ever truly refined and resourceful. Some of the older ones were sent to Vietnam to “win hearts and minds,” but what they really did was steal the dreams of people who had never disturbed their peace. Those irreclaimable acts would haunt their sleep long after that war was forgotten at home. A war they brought home to their loved ones. And, after they returned, many of their sons became undone in prisons and later in deserts and mountain ranges that were worlds away. Invisible wounds festered and became a terror to the loved ones they would not let in, or to those they pushed away.

He would often think of these afflictions whenever he went back to the basics of a dry cell. But that night, he heard something other than his thoughts and memories. First, it was the sound of death, which he immediately recognized from Oliver Stone’s Platoon.

It was Adagio for Strings. The scene where Elias is shot down with his arms stretched out in the crucifix pose. Went out like a G on a double-cross. It was coming faintly from a portable tape recorder that a staff member was listening to. He knew about the melancholy of borrowed time, but didn’t know that sorrow could sound so good. He tapped on the observation window and respectfully signaled for him to turn up the volume. This request was denied, but he did turn on the cell’s mic to pipe in the music.

Next he heard movement. It was Antonín Dvorˇák, and it was a sound that his heart would forever covet. The sound that he would later hum to himself in tens of dozens of other cells. The sound that would help him imagine new worlds. Music had always been important, since his days in juvie when the other little gangsters sang a capellas to one another. If freedom had a sound, it was the songs they sang to one another the night before each one was sent away. They sang to one another because their lives were too short and their sentences too long. They sang to one another to create moments of happiness in the saddest of places.

Later, he would learn that when Dvorˇák was the director of the National Conservatory of Music in New York City, he went on a tour of the US, and when he returned to New York and was asked what he thought was the original American music, he tied it back to the drums and chants of Native Americans and Negro spirituals. Colonial cousins of the colonial wound of indignity. The country’s original sins committed against those who continued to weave the cosmos even when they were drylongso. The man his children affectionately called “the Moor” found himself back in Prague shortly thereafter, but Dvorˇák did presage rock and roll. Songs with morsels of sorrow that nourish satisfaction. They gave the world their pain to give it some joy, and ain’t them bodies saints.

C. T. Mexica is a reformed gangster and former prisoner with a doctorate in comparative literature. He is a 2018 Art for Justice Bearing Witness Fellow and a 2019 PEN America Writing for Justice Fellow. He plays tiddledywinks competitively and is currently writing a memoir.

More Web Exclusives