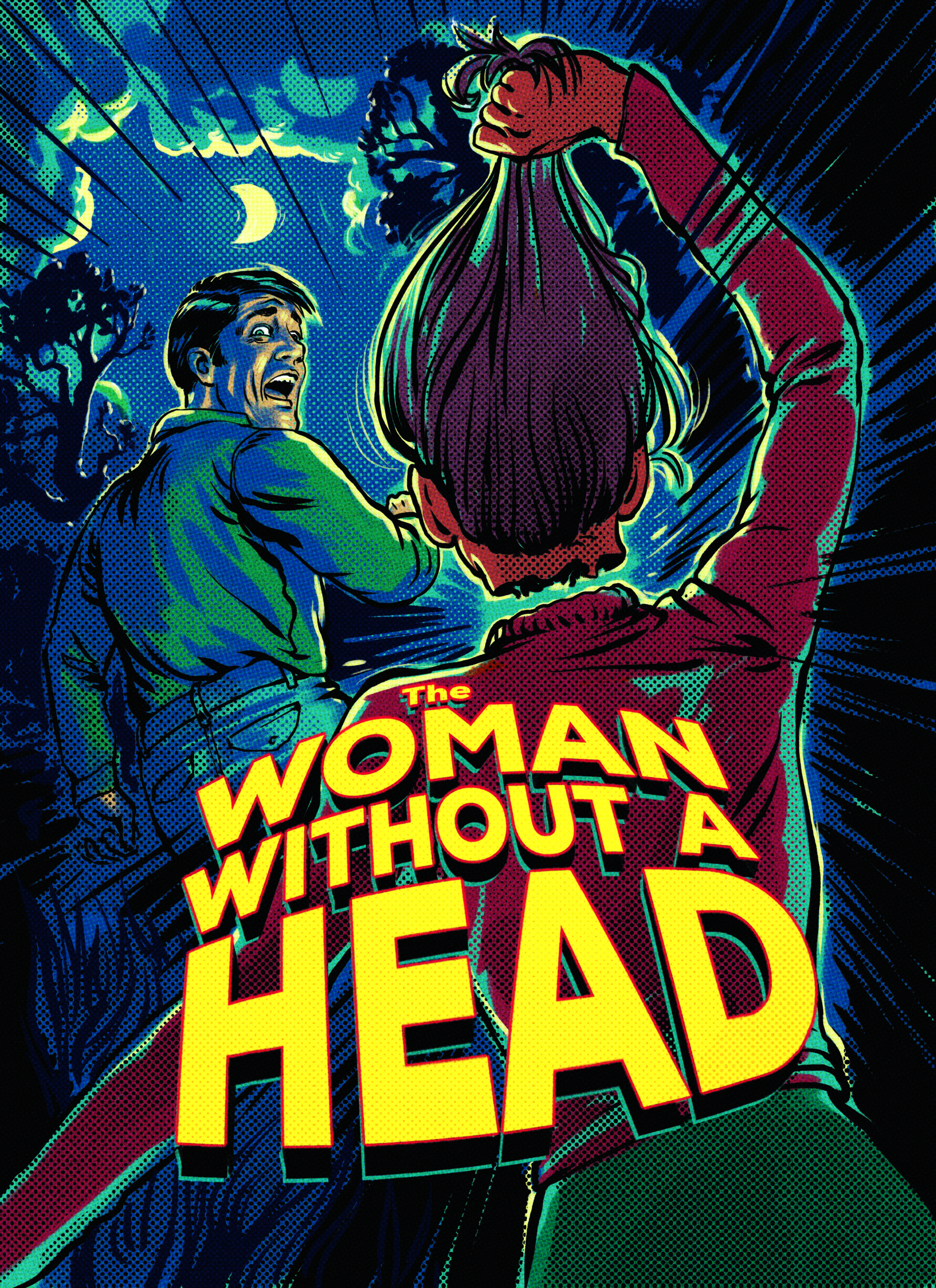

The wáay’s—the sorceress’s—head detached from its trunk, jumped out of the family home, bounced around, and moved down the streets in the middle of the night. It strolled through the village among the pitiful howls of the dogs and the quick steps of the surprised passersby outside at this evil hour.

Night was catching up with dawn, but the insomniac grandmother shucked her story amid an audience of gaping children. I clearly remember her white hair, her serious countenance while she talked, and her thin legs with which she rocked lightly in her hammock, her feet on the ground.

The husband didn’t know his wife was a sorceress, explained the grandmother.

Every night the wife silently got out of bed, uttered certain mysterious words, and moved her hands in the air, above her husband’s face, so that he would sleep more deeply.

Once her husband was fully asleep, she went to a corner of the house where she settled in and the impossible happened: her head detached itself from her body and bounced to the ground. It went to the door, opened it—I don’t know how—and went out into the street for its nighttime jaunt.

Who knows if it did evil deeds to other people? Be that as it may, the fact that a human head went for a jaunt alone in the night when the village was asleep was in itself horrific. Have you heard the pitiful howling of dogs? Barks at first, then yelps mixed with howls, and in the end only baying, as if somebody were throwing rocks at them. The scariest dog desperately scratched at the door to get in. When they heard this, the elders used to softly say: “Je’e’ ku taal le wáayo’,” or “Here comes the wáay.” If any children are awake at that time, their parents immediately hush them. And the neighbors can sometimes clearly hear the ku taal u kilin—the thunderous tread—of the thing.

With this kind of incident, one might expect that the terrorized villagers would organize and search for the origin of the events until they found the house from whence came the head.

One day, a man chosen by the families spoke with the wáay’s husband: “Something strange is happening in your home. I shan’t tell you what because you wouldn’t believe me. But so that you see it with your own eyes, tonight go to bed as usual and pretend to be asleep. Put a little pepper in your eyes so you don’t fall asleep.”

So it happened, and the poor husband verified that one never knows one’s wife well enough.

“You’ll do as we say,” they told him the next day. “Tonight, when she goes out, put a handful of salt on her neck where the head comes off. She won’t be able to do anything.”

When the head went out for its nocturnal jaunt, the heartbroken husband got out of bed, sprinkled salt where the head had come off, and sat down to wait.

Very early in the morning, his wife came back, and when she went to put herself in her place to reawaken, she found she couldn’t fit on her body.

She tried several times but couldn’t return to her place. Then she began to cry, asking her husband what she’d done to him and imploring him to help her, but she got no answer.

She told him that she loved him, that she’d never done him any harm, and asked him to take pity on her, but she still received no answer. Heartbroken, she left the house and wandered around until, perhaps finding she was lost, she threw herself into a well. She never came out of it.

The body was buried, and the husband left the village forever.

Years later, in a village in the eastern part of the state, I heard a nearly identical story, though this one concerned a man, not a woman. The man without a head? a friend who had been affected mockingly asked and then launched into a speech about the nervous system, referring to the sympathetic and parasympathetic, in which he made an argument about the impossibility of a man surviving without a head. ![]()

José Natividad Ic Xec was born in Peto, Yucatán, and lives in Merida, the capital of the state. He worked for the newspaper Diario de Yucatán for many years, then became independent and created his own editorial project, Elchilambalam.com. He also teaches Mayan and Maya literature.

Nicole Genaille is a French honorary professor of classical languages and a specialist in the Isiac cults. She now studies Mayan and Maya civilization. She is a friend of José Natividad Ic Xec and translated his book into French as La femme sans tête: Et autres histoires Mayas (Presses de l’ENS, 2013) with notes and a postface.

Illustration: Sam Hadley