Angela faked the seizure on a Tuesday. She’d meant it as a joke—a bit of post-lunch humor to lighten the mood—but no one thought it was a joke and she could see that it wasn’t funny, that there was no circumstance in which it might have been funny. She blinked her eyes a lot coming out of it, glad she’d put on mascara that morning.

Her coworkers were solicitous, even the ones who disliked her, and Corrin made her a smoothie with blueberries and flax seeds, which was a random but kind gesture. After that, Mr. Kenny insisted his secretary drive her to the ER.

Angela buckled herself into Dana’s hideous yellow hatchback and said, “Take me home please, 214 South Church Street. I’ll call my doctor when I get there.”

“Mr. Kenny said I should take you to the ER.”

“Mr. Kenny can handle his medical affairs and I’ll handle mine.”

“Of course,” Dana said, “right.”

Angela took a sip of the smoothie. She wasn’t going to mention HIPAA, but she could. She doubted anyone in her office knew what was in the law, but they took any mention of it very seriously. They drove in silence. Angela rested her head on the window, and it bounced lightly against the glass, making her headache worse, but it was pleasurable nevertheless. She was hungover and wondered if that was why she’d done it. Why had she done it? It was a terrible thing to do. Perhaps illegal. Like yelling fire in a crowded theater. She wondered what the difference was between theater and theatre. She remembered looking at each of her coworkers’ faces—their big noses and draping hair, how people became unrecognizable in such positions—and thinking how many hours of their lives they spent together. Most of them had been together for years and years and they hardly knew each other but harbored plenty of resentments; it was like a school project where one person does all the work, but it lasts twenty years.

As Dana pulled into her complex, Angela said, “I’m all the way in the back, just follow the road and watch these bumps.” When they went over the first one, she said, “I have got to move,” though she liked the complex, and she liked being all the way in the back where she felt tucked in.

Dana parked and got out. Angela was surprised by this but didn’t say anything. She unlocked the door to her first-floor, one-bedroom apartment—a garden apartment it was called—and Dana followed her inside, helped her get situated on the couch with a pillow and blanket.

“What can I do?” Dana asked. “Can I get you some water? Start a load of laundry?” she chuckled. “Tell me.”

“I’m fine. I appreciate the ride.”

“What about your doctor? Do you want me to call him and make an appointment?”

Angela wished her doctor was a woman so she could correct her. All of her doctors were men, even her gynecologist. Even her dentist, and the guy who checked her moles. “I just want to rest for a few minutes,” Angela said, and she looked directly at Dana, who had perched herself on the arm of her good chair.

They held each other’s gaze. Dana was wearing a fitted bright-blue dress that looked okay but not great. It was fashionable and appropriate for the season. It hit at a weird spot, though, midcalf, where her thick calves were thickest. Her legs hadn’t been shaved in a long time. Dana was in her late twenties or early thirties, and this was more acceptable in her age group. Shaved pits, legs, bush—all optional. Or maybe just the pits and legs were optional. Angela had quite the bush, but she shaved her legs and armpits every other day.

They were opposites but the same. Old or young, women conformed, even if it wasn’t obvious, even if they didn’t let you see it. No one had seen Angela’s bush in years. She thought about the last action she’d gotten—a married guy fingering her in the bathroom at a concert. When the knocks came, they’d gone quiet, looking at each other, waiting for whoever it was to go away. It had been exhilarating, she’d loved every moment of it, but she still wished she’d shaved or waxed. He might’ve called if she had.

Dana went into her kitchen and poked around. The kitchen was a wreck. Angela hoped she didn’t have to use the bathroom.

“It’s gross in there. You shouldn’t be in there.”

“I’ve seen worse,” Dana said.

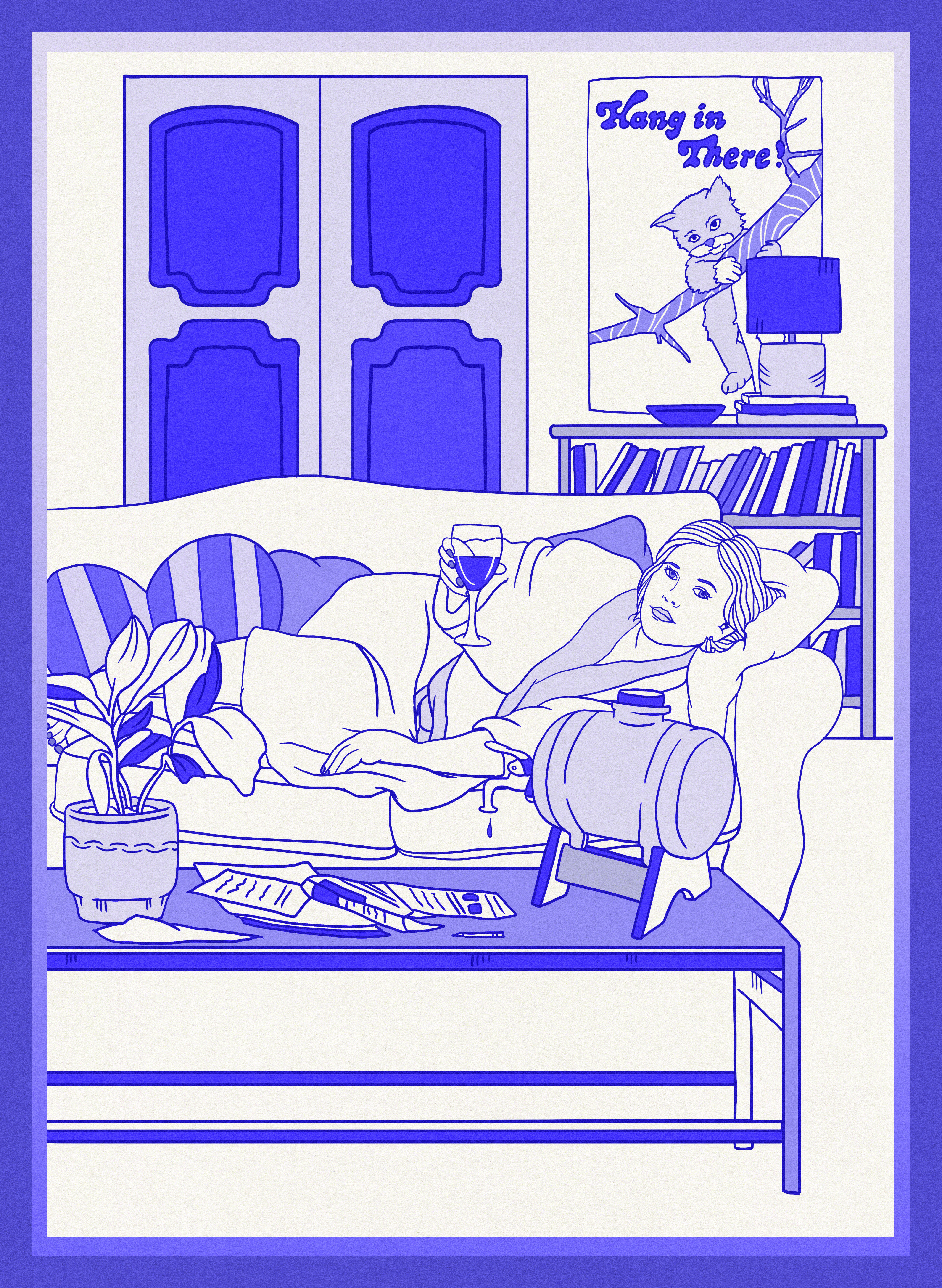

Angela had let the dishes pile up for a week or longer, and it smelled. She’d smelled it as soon as they’d walked in. At first, letting the dishes accumulate had been a way to teach herself to be less rigid, more flexible—to learn to live with the mess of life instead of fighting against it—but it had gotten out of hand. She looked around her apartment and saw that everything had gotten out of hand, and yet she didn’t feel any more flexible. Her rigidity had only shifted. She’d become preoccupied with her teeth, flossing after every meal and going through a box of whitening strips in two days. She had splurged on “the Cadillac of lighted makeup mirrors” so she could check for cracks and discoloration. There were other shifts, too, ones she wanted to think about even less, that she was not going to think about. Like how she only bought wine in a box with a spigot.

Dana rinsed and scrubbed, began loading the dishwasher.

“You don’t have to do that,” Angela said.

“It’s either this or go back to work.” She turned off the water and said, “I hope I haven’t overstepped.”

“Oh no, you’re not overstepping.”

“At work I’d just be watching the clock . . . Don’t get me wrong, I like my job, it’s a good job.”

“It’s a great job,” Angela said. “I wouldn’t have stayed there thirteen years if it wasn’t, but sometimes you just have to play hooky.”

“I have permission,” Dana said.

Angela thought about explaining herself, how she’d always been the kind of person who wouldn’t leave a cup in the sink, even if it was rinsed, that the mess was an experiment that had gone badly, like so many of her experiments—she wasn’t a scientist!—but she barely knew this woman and didn’t want to know her. Dana had only been in the office for three or four months, and she was the boss’s secretary, didn’t mingle much with the general office population, insofar as they mingled. Angela thought of her as big boobs and bouncy hair inside of a glass box.

“Should I start the dishwasher or will the noise bother you?”

“You can start it.” Angela closed her eyes. She wanted this woman to leave, but Dana had moved into the living room and was folding a blanket. Gathering a pile of self-help books and placing them on the wrong shelf. Once Angela had been reading a book about making friends—something like How to Make (and Keep) Friends for Life!—and had unashamedly shown it to a woman who’d asked what she was reading. The woman had frowned and stammered before walking away, and Angela felt a deep shame, an old familiar feeling but new. Self-help books weren’t as embarrassing as they’d once been, though. Lots of people read them and talked about them, and it was viewed as a positive thing to want to better oneself.

As if to prove Angela’s point, Dana held up one and said, “This is so good.” It wasn’t one of the more embarrassing ones, but a classic: The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz. Angela remembered when she’d first read it, and how it made her brain feel like it was changing shape. Like she could feel her brain making connections that hadn’t been there before. The Four Agreements had led her to other books, and then others, as she searched for more brain-altering ideas, but they were few and far between.

“By the way, are you on any new medications?” the secretary asked. “New meds can trigger a seizure.”

Angela pretended to be half-asleep and mumbled that she was going to close her eyes.

“Or maybe you’re photosensitive?”

“What?”

“You know, flashing lights. You might’ve watched something that triggered it.”

“I don’t think so?”

Dana watched her for a few more seconds—some of the longest of her life—and then walked to the door. “Okay. I’m going to go now, let you get some rest.”

“Thanks again,” Angela said.

“I’m gonna hit the coffee shop on Fortune. Probably sit in there and stare out the window for a good half hour.”

“Enjoy.”

She heard Dana’s car start, reverse, drive away. Angela peered out the window, watching the hatchback hump over one speed bump and another, Dana’s bouncy head bouncing. Then she got a mug of wine from the fridge, the spigot so easy to push, and stripped out of her clothes. She donned a fat robe and put on Grey’s Anatomy. She was late to the party with Grey’s and only started because her sister told her she had to. They hardly ever liked the same things, but the older they got the more it seemed like they might.

In the first episode, there was a teenage girl driving Meredith crazy, paging her because she was bored, because there was nothing on TV. The girl was clearly being set up for something tragic, and then she had a grand mal seizure, and if they didn’t find the reason for the seizures, she was going to die. Time was running out, McDreamy said. What did it all mean? Angela wondered. She refilled her mug.

She watched two episodes and decided she was in. What a pleasure to have something like seventeen seasons to keep her company, which might as well be a million. She texted her sister the good news and napped for an hour. Then she watched another episode and declined a call from her friend Nicky, who almost certainly needed someone to feed her cats for the next week. Angela had fed her cats a dozen times and had never felt sufficiently appreciated. She’d told herself she wouldn’t do it again, and she wouldn’t. Pretty soon Nicky would stop calling. She had been mighty persistent, though. Angela could see her mumbling, becoming agitated as the ringing went on. But this wasn’t Angela’s fault. Nicky should have offered more than a cheap souvenir or a token payment. And to be fair, Angela should have asked, but she didn’t feel like she should have to ask. Nicky should have known she was taking advantage and corrected the issue on her own. Angela wasn’t her teacher, her mother.

On the cusp of drunk, she ate a couple of Thin Mints from the freezer and realized she was ravenous, at which point she drove to Taco Bell for two chicken quesadillas and a Mexican pizza.

She ate while watching another episode and got into bed early. While lying there, she felt some guilt—and buried beneath that, horror—but there was excitement too. Something unusual had happened, she had made it happen, and everyone had been so nice to her; her kitchen was clean, her books neatly stacked. Overall, it had been a good day.

![]()

The following morning, her coworkers stopped by her desk to ask how she was doing or to give her “a little something.” She received a get-well card drawn by a child (wild-haired family of four, a dog, and a snake), a bag of caramels, a tiny cactus, and a gift certificate for a massage. She hadn’t received so many gifts in years. People seldom give a single, childless, forty-seven-year-old woman anything. She felt like crying and must have looked like it because three people stopped to pat her on the shoulder.

Dexter, who’d given her the card, circled back. “I forgot to put this in there,” he said, handing her a Starbucks gift card.

“Oh, that’s so nice. Thank you.”

“There should be at least twenty-eight dollars on it.”

“Great, I’ll enjoy it.”

“Might be thirty bucks . . .”

“Who has the snake—your son or your daughter?”

“Mine,” he said, proudly. He was just standing there, but Angela imagined him with his hands in his pockets, rocking back and forth on the balls of his feet while fondling himself. That was the kind of energy Dexter gave off. “He’s thirty-six years old.”

“Wow,” Angela said. “That’s a long time to have a snake!”

“Almost as old as me.”

“Wow,” Angela said again. “What’s his name?”

“He doesn’t really have a name.” Dexter paused and Angela knew that a name was forthcoming. “I just call him Mr. Snake.”

“Classic,” she said, and Dexter went back to his desk and Angela wondered how old he was. He looked to be about fifty, but maybe he was only in his early forties? Or perhaps even his late thirties? This made her feel worried. How old did she look? Would someone mistake her for a woman in her fifties or, God forbid, her sixties? She looked around at the others and tried to guess their ages. When they had birthday parties, there were never any numbers on the cakes and only three candles, enough to blow.

As she worked, everyone seemed to be sneaking peeks at her, waiting for her to have another seizure. Her workload was half of what it was on a normal day so she scrolled Facebook and ate caramels, marveling at how delicious they were. The gold wrappers were a bonus. She loved everything about these caramels. If she had a million dollars, how many bags of caramels would she buy? She would roll around on a bed of gold caramels. She went to the bathroom and brushed her hair, which was long and graying at the temples. Why shouldn’t she make an appointment at a salon? She didn’t think enough of herself, that was her problem. She had always cut corners unnecessarily.

That afternoon, when her boss called her into his office for her quarterly review, he marked her “excellent” in every category. This wasn’t out of the ordinary, she was usually pretty excellent, but maybe not quite this excellent. Then he asked if she needed some time off and she said she didn’t, but she had a doctor’s appointment Friday and would need to leave early.

“Of course, of course,” he said as he held the door open for her and patted her on the shoulder. As an office, they had decided that pats on the shoulder were okay, though they should be light and infrequent. They had all agreed to this, and no one opted out. Angela didn’t mind being touched on the shoulder. She was born in the seventies, a time of secondhand smoke and no seatbelts, children roaming the streets until their mothers whistled for dinner. Her brother had slept with three babysitters before her parents hired an old lady named Bea.

Dana stopped by her desk to ask how she was feeling. Dana hadn’t given her anything, which was disappointing. Angela put her finger on the tiny cactus, which had a serious lean, careful to avoid the needles. “I’m feeling okay,” she said. “Better.”

“I’m glad. You should probably take that guy home, he needs sun to thrive.”

“Hm, makes sense. They live in the desert . . .”

“Not too much sun, though. Too much and it’ll turn yellow.”

“How do you know this?”

Dana shrugged. She was wearing another breast-showcasing outfit, this time in pink. Angela wondered what kind of undergarments she wore, if she had a full bodysuit under there. She wished she had some younger friends so she could ask these questions, but her youngest friend was Nicky, who was in her midthirties, and she wasn’t speaking to Nicky. There was a chance she would never speak to Nicky again because she wasn’t going to take care of those cats, no way no how, she couldn’t do it, she wouldn’t let herself be taken advantage of again.

“Were you able to get in touch with your doctor?” Dana asked.

Angela tilted her head and squinted, hoping to make clear that Dana should mind her own fucking business. “I have an appointment on Friday.”

“Oh good, I’m glad. I’m sure it’s nothing, a new medication or light strobe or whatever.”

“I wanted to thank you again for taking me home, doing the dishes. That was over and above—over and beyond. Really.”

“Of course.”

Angela bumped her mouse, positioning her hands on the keyboard. She watched Dana’s pink ass as it rounded the corner. Was Dana suspicious or was she trying to be nice or was it something else? Perhaps the boss’s secretary was falling in love with her. That would be unexpected, but Angela had kept up her body—she had a stationary bike and a treadmill and free weights at home, which she used to use regularly and had been meaning to start using again—and she had nice eyes and decent hair and she probably seemed mysterious because she kept herself apart, as if she was something special. She had always been one of the prettier friends in her friend group, if not the prettiest. But no one thought about a woman of her age in those terms. No one had called her pretty in a long time.

She went to the bathroom and washed her hands. One of the claims reps came in, Felicia. They said hello and Felicia went into the handicapped stall and farted obscenely. Angela continued washing her hands. She didn’t say anything, of course she never said anything, made any kind of noise or acknowledgement whatsoever, but she’d always found it curious, this unabashed gas when you knew someone was in the bathroom with you, someone you had just interacted with and would have to interact with again seconds later.

Angela would look at her and know . . . what? What would she know? That Felicia was the kind of person who let loose in a place she was expected to let loose? Angela felt like the world might be divided along these lines. The people who could fart and shit loudly in a public bathroom and those who drove home recklessly, nearly soiling themselves to get there.

She played around on Facebook again, not even pretending to work. She sent a message to one of her high school friends named Katie, asking if she recalled the time they were lost in their hometown, circling the west side for hours in Katie’s stepfather’s truck. They’d stopped and bought a map because they’d wanted to figure it out on their own. Katie was online and wrote that she vaguely recalled the experience, but what had made that day memorable was the man at the gas station masturbating. Angela did not remember this part. She tried to visualize a man looking at them as he went at himself, the two of them peeling out and laugh-crying or perhaps just crying. If this had happened, why couldn’t she remember the most important detail? They hadn’t been lost for more than a few hours. And the two of them had frequently been lost. They were the sort of friends whose general cluelessness multiplied tenfold when they were together. If Angela had been smarter, she would have befriended people who were competent and sure of themselves, but those people had better options.

Her boss patted her on the shoulder, his second pat of the day, and leaned in in a way that made Angela think he might embrace her, but he only rapped his knuckles on her desk and told her to go home and get some rest. She thought about the time she’d been at church and went in to hug an old lady—a distant relative—and the woman said, “Not on the lips,” as if she was going to kiss an old woman on the lips! She would have never, never in a million years, and yet the old woman must have thought she was going to or she wouldn’t have said it. Angela had no idea what her body was doing sometimes, her face, what people thought her body or her face might do. She’d found it hilarious at the time, but had continued to think about it and each time she thought of it, it was less funny. Why would the woman have said such a thing? Angela hadn’t wanted to embrace her at all, had only gone in because it seemed she had no choice.

“I am tired all of a sudden,” she said. He smiled down at her. He was a preacher on Sundays, and he liked to smile down at people. She dropped the bag of caramels into her purse and held the cactus with two hands.

At home, she set the cactus in a spot where it would get sun throughout the morning and early afternoon. She would have to watch to make sure it wasn’t turning yellow. She checked Facebook again and Katie said that another memory had come to her: the time Angela got drunk and fell down the stairs at Scrooge’s and her skirt flipped up.

Angela remembered this well because her panties had been oversized white ones—the most unfortunate kind of baggy old droopy things. She hadn’t been wearing a skirt that day, but a dress, one she would never wear again, not once, even though she’d loved it. Every time she opened her closet and saw it hanging there, it all came back: the gravel in her busted knee, the boys laughing and even some of the girls, her friends, before they’d helped her up. The boys called her “granny panties” for weeks to her face, and behind her back they called her “big gran,” likely for years.

Angela wondered why Katie would bring up a cruel memory when she had brought up an innocuous one, one that she’d thought was humorous, at least without the masturbating man, and Angela didn’t remember a masturbating man. She was pretty sure this had happened to Katie on some other day. Had Katie been mad and this was her way of lashing out from hundreds of miles away? Angela tried to remember a humiliating experience about Katie but couldn’t come up with anything. She tried to recall the humiliations of any of her friends—someone bleeding through their pants, a naked Polaroid circulating around school—and couldn’t recall anything, not a thing. Angela had plenty of humiliations that haunted her. Who had access to them, and why couldn’t she recall any of theirs? She cried until her eyes were red and her face was puffy.

That evening, after three episodes and a bowl of buttered noodles, Angela googled “seizure.” She read about the four types of seizures. She learned that if she had another within a short period of time, it would be considered epilepsy, and she didn’t know if she wanted to be epileptic. She would have to be willing to commit, which would be a fucked-up thing to do. Now it was a one-off, a lapse in judgment, an odd but brief break from reality or whatever. Even as she was telling herself all of the reasons she shouldn’t do it again—that if anyone found out, she would be ruined—she knew it was a question of when, not if.

![]()

She started seeing seizures everywhere. In every TV show and movie, in every article she read, people were having seizures. Had the seizures been there all along, or was it like the car thing? Like you buy a white Volvo and all of a sudden you notice all the white Volvos in the world. Angela’s brain was making connections it hadn’t made since The Four Agreements. Also, she had written Katie a dozen fuck-you messages but hadn’t sent any of them, which was curious.

At work they were watching her, waiting, and Angela was watching herself. She could do it at any time. She had a lot more information, and if any of them were seizure experts, she figured she would do better this time around. She had always thought she could be an actor.

On the following Tuesday, her brain and body knew it was time. She was hungover again. Why she liked to get drunk on a Monday night—the whole week ahead, the worst day of the week to do it—well, it just seemed to happen. No foaming at the mouth, but she let a few globs of bubbly spit run down her chin and pool on her shirt. Dana assumed the role of caretaker. Dana was her girl, whether she wanted her to be or not. On the one hand, she wanted her to be. Dana was an unknown entity within the office. Angela believed she was from Iowa, and she had never met anyone from Iowa. On the other hand, Angela didn’t know what was on the other hand, but she had come to the conclusion that Dana was smarter than the rest of them combined.

Her boss handed her a Subway napkin and she blotted her mouth. She looked to see if it still listed all of the subs and their calorie content and was pleased to see that it did. She missed those chocolate chip cookies, three for a dollar back when she was frequenting her local shop.

Dana drove her home. Angela told her to watch the speed bumps. Dana looked at her and Angela turned her head to look out the window.

Dana took the keys and unlocked the door as if she was in charge. She moved the cactus to a place where it would get the perfect amount of light, or so she said. Then she sat in her good chair while Angela reclined on the couch with a blanket and pillow.

“You think you could make me a smoothie? It made me feel better last time.”

“Sure, what do you want in it?”

“I’ve got some bananas and frozen fruit, the blender’s on the counter,” Angela said. “Are you a good smoothie maker? Do you need me to look up a recipe? There’s almond milk and regular. I like almond milk in my coffee and cow milk in my cereal, but I’m not sure which I’d prefer in a smoothie.”

“I don’t drink cow milk.”

“A lot of people don’t anymore.”

Dana opened and closed the freezer, opened and closed the fridge. “Do you have honey?”

“In the pantry.”

Angela hoped she wouldn’t ask any more questions. She wanted the smoothie that Dana would make for herself. Angela knew what kind of smoothie she would make, and she didn’t want that. She closed her eyes and listened to the blender, listened to the clack, clack, clack of Dana’s high heels.

“I hope you’re thirsty,” Dana said, so close Angela could feel the fabric of Dana’s pants brush against her arm. Polyester. She opened her eyes to a green-colored smoothie.

“I put spinach in there.”

Angela sat up and took a swallow. It was just like she imagined. Dana sat in the chair and watched her. After a while she said, “So these are the first seizures you ever had?”

“Yes,” Angela said, wiping her chin. She hoped she didn’t get a pimple. Sometimes, even though she was old, she still got pimples on her chin.

“How have you felt otherwise?”

“Okay. Like normal, though I’ve been more tired than usual.”

“You haven’t been sleeping well?”

Angela acted like she was considering the question. “Not really, no.”

“What’d the doctor say?”

“My bloodwork’s fine . . . He’s going to run some tests next week.”

Dana did the dishes again, which were smelly and stacked up. She ran the dishwasher. Angela imagined Dana taking off her clothes, one item at a time, dancing for her, moving her hips in a slow circle. Propping one high-heeled foot on the coffee table. Angela had never been with a woman, couldn’t remember ever thinking about a woman in this way.

“Do you mind if I use your bathroom?”

“Go ahead,” Angela said. She had planned for this, to some extent, and had cleaned somewhat, put away her embarrassing things, somewhat. She listened to Dana’s piss hitting the bowl, the flush. How awful it was to be human.

Dana emerged from the bathroom picking at something on her blouse, a piece of thread or a flake of dandruff, and let it drop to the floor.

“It’s too bad you’ve been stuck taking care of me like this. Like it’s part of your job now.”

“It’s no trouble,” Dana said. “I actually like this part of my job.”

“I don’t really need your help.”

“I know, like I said. I like doing it.”

She didn’t have a crush on Dana. She didn’t want Dana to be her friend or her girlfriend. What might they possibly do together? Garden? Yoga? Go out for brunch and get excited about bottomless mimosas?

“My sister’s epileptic,” Dana said.

“Oh?” Angela said.

“Runs in my family. Not me, I’ve never had one, but my mom and sister and one of my cousins.”

“I’m sorry to hear that.”

“Yours are different from any I’ve seen,” Dana said, “but I’m not an expert.”

“Don’t shortchange yourself,” Angela said. She imagined Dana recording their encounter, pressing a button on her phone to hear Angela admit she was a faker, a malingerer. Playing it for their boss. “I think I should get some rest now.”

Dana left. Angela closed her eyes. Then she opened them and drank her smoothie. There were people she felt ugly around and people she felt pretty around and people she felt neutral around, neither ugly nor pretty, not conscious of ugliness or prettiness, fatness or thinness, anything to do with looks—they might as well be plants, some that had been watered a bit more and others that had been watered a bit less, but that was the rain’s fault. Those were the people she wanted to be around most, the people around whom she could forget her body, forget about having a body, being a body. She didn’t want to have or be a body, didn’t want to think about her body, everything she put into it, the harm she was doing to it, the things she swallowed, all of it nonstop, always ingesting and purging, in and out.

She composed a note to Katie that began, “Dear Katie, you always were a fucking cunt.” She didn’t hesitate this time before hitting send. ![]()

Mary Miller is the author of four books, most recently the novel Biloxi. Her stories have appeared in The Paris Review, McSweeney’s Quarterly, and American Short Fiction, among others.

Illustration: Jess Rotter