Dear fellow delinquents,

Because our counselor—Vlad Siren, whose name sounds suspicious to me—asked us to write a bunch of dirgeful crap to be read aloud here in Tophet County Detention about whether we felt ashamed of ourselves, and because Trusty John claimed he suffered from a sudden and severe case of graphospasm (his letter was blank) despite his priapic drawings of genitalia, I’ll make this short letter as insightful and therapeutic as possible. We’re faced once again with the task of having to sit alone under the pressures of confession and guilt and give the staff insight into our thoughts and motivations, no matter how strange or selfish, so that they know where to refer us for long-term treatment, if we even need it, and to help us understand ourselves better with a goal of rehabilitation and self-forgiveness and a whole-hearted freedom from shame, with the primary, predictable, and asinine icebreaker being: What’s a memory of feeling ashamed?

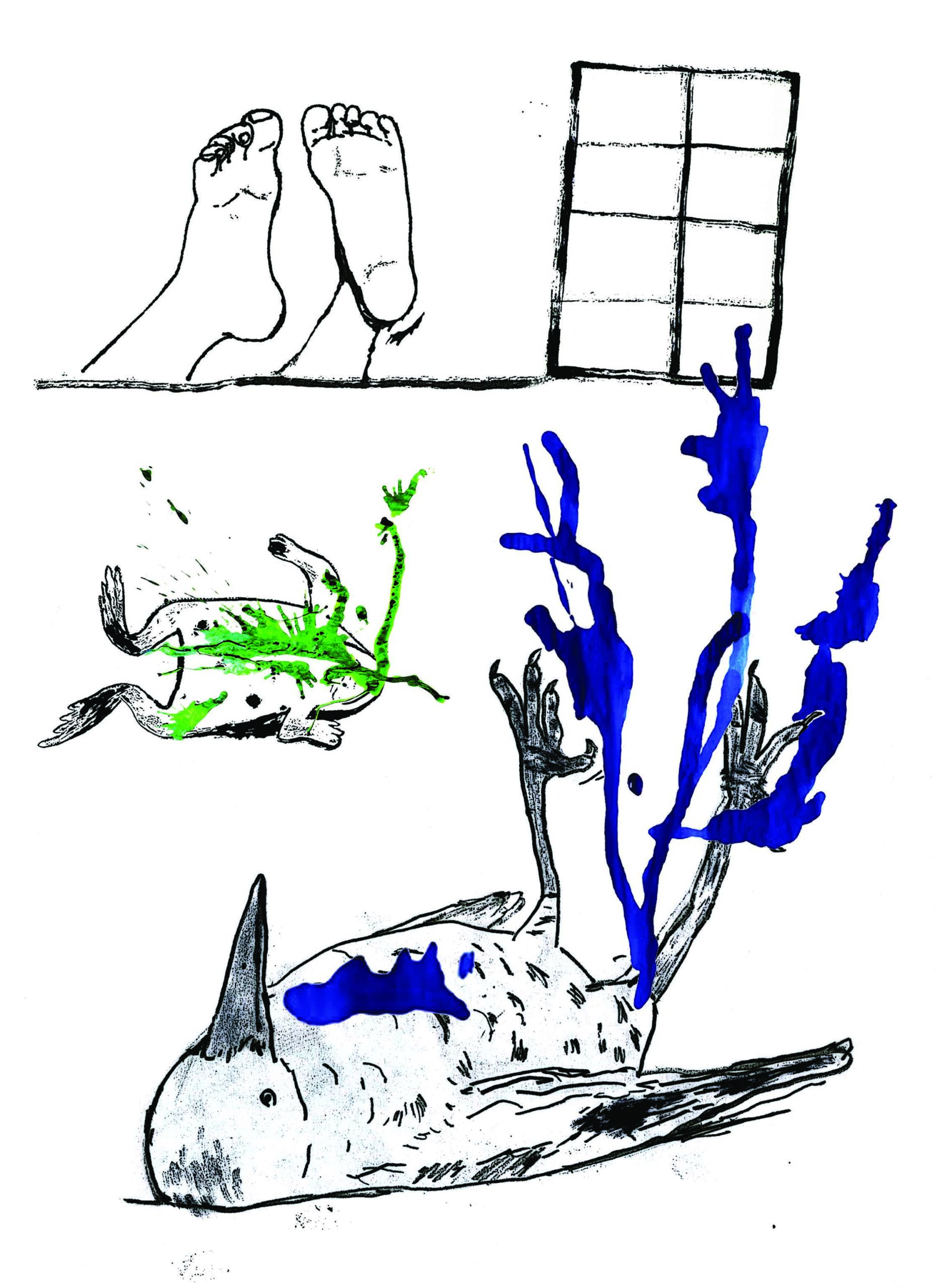

A few years ago, I drove myself to the most horrific visions: I began seeing dying birds. Hallucinations like this, when a room would fill with birds who fell to the floor and twitched in suffering as if they’d been shot, only confirmed the ancient certainty that the strongest feelings of envy, jealousy, and especially anxiety exist within ourselves, in our minds and hearts, and that the people we admire and envy most are the very people who create the fear that lives and breathes inside us. Anytime there was an open window, I would see birds sweep into the room and fall to a slow death. I saw cardinals, blue jays, sparrows, grackles. I saw crows and finches. I saw colorful island birds, twitching, trembling, their wings and necks broken, calling out for help. The visions started sporadically but grew more abstract and detailed the older I got. I saw frogs, hundreds of them, gathering in a room among the dying birds and croaking to their own deaths. Frogs with protruding violet tongues, blinking slowly in the light until their eyes closed and they stopped breathing. I would rush out of the room and tell my dad or mom, who escorted me back to show me there was nothing there, such a sly and evil gesture, playing tricks on me, threatening me with the consequences of demonic possession if I continued to watch horror movies on cable TV, and yet they returned to the living room to sip wine and watch their own movies with nudity and strong language. On occasion I would storm out of the back door while spitting the froth from my stomach bile and stare into the glaucous glow of moonlight and see another frog or dying bird twitching, trembling, suppurating a yellowish custard from their eyes, and because we lived near a river, this fool feared the frogs were arriving from the sleech to seek shelter in our house. They appeared in my dreams, parading in from coastal villages while I heard my father shouting at my mom from another room, several of them crawling into my bed only to die at my feet or on my legs like a wet, heavy blanket. My parents started taking me seriously when I woke them with my screams and they found me cornered in my bedroom at four in the morning breathing the same air as them yet feeling asphyxiated and coughing, kicking at the dead birds and frogs surrounding me. I left a trail of crumbled crackers from the pantry that led from my room all the way out the front door and into the street. For a while I could not find a moment of rest, worried these creatures were invading our home and me specifically for no other reason than mere torture. My parents worried I needed to find a hobby, so my father forced me to watch baseball with him, collect baseball cards, and listen to sports radio. We played dominoes, chess, checkers, and board games for many nights in a row. “Learn to be great at something,” my father said. Like so many other children I was told, after all, that I could grow up to be whatever I wanted to be, no matter what the circumstances, and that as long as I worked hard my dreams would come true; it was the American Dream, my father continually told me. Work hard and you find success. You can be anything you want. Hard work builds character. I was certain, even at that young age, that I wanted to be famous, and my parents took it seriously enough that my mom often accompanied me to the public library and let me pick out art books. I was particularly drawn to surrealism—Salvador Dalí, Frida Kahlo, Leonora Carrington, Joan Miró. At night I studied their work, emulated it, and wrote stories to accompany the drawings. My first story I ever wrote, age six, was titled “The Sad Roach,” about a roach who wants to be a bird so he can fly but instead drowns in a pot of stew. The more I painted, and the more I wrote, the more I felt at ease, less anxious, and happier. I eventually learned to dismiss the visions of dying birds and frogs, even though they continued, because I knew I was safe and they were harmless, but I still kept my guard up anytime I saw them near my bed at night or twitching in my closet. My parents, in strong denial of any mental illness, dismissed these delusions as hyper imagination and encouraged me to use that anxiety and energy toward my art.

Around this time, I first experienced the panic. It was something that led to great shame, mostly due to my own puerile nescience as my father lay drunk in bed after his brother’s funeral while the rest of the guests mingled quietly in the living room with my mother. I found him mumbling something as he rolled over in bed and hung one arm off the side, which was the first time I had seen him that drunk. I sensed the struggle in his body and dizzying mind, heard his throaty cough and groan, and thought the best thing to do was to help my mother with the guests in the living room, but as soon as I entered, everyone stopped talking and looked up at me at the same time. To say this moment was terrifying is an understatement, because all the sudden attention on me felt like I was suffocating, or having a heart attack and needed to vomit. I was certain everyone was staring at me because I had disappointed my family, the dark sheep if you will, always getting in trouble at school and at church, and somehow I felt responsible for my father’s drunkenness that day and felt like everyone knew it.

While the burning pain hit my chest, I was able to retrieve my inhaler from my blazer pocket and take two quick pumps before losing my breath, thankfully, but it didn’t help. The cads who gambled and drank in secret with my father lurched toward me just as I blacked out and fell forward on the hardwood floor, bloodying my nose and cheek. I woke on my back to them breathing down on me with pimento cheese breath, their jowls sagging and cold hands on my jaw and forehead. “Breathe,” they told me. “Are you OK? Breathe.”

The panic attacks continued after that, and every one of them grew worse, so that soon enough I wasn’t able to walk into a room with more than three people in it, which is one of the reasons they put me in the alternative school in North Creek. Try getting dizzy anytime a group of people look at you, or vomiting in church or at the mall. Sixth-grade graduation gave me the stomach cramps, but my father blamed it on the Frito chili pie and Kool-Aid I’d had for supper. I won’t tell you how strong my antianxiety pills are, but it took three different times for me to black out before my father agreed to get me put on meds.

My father is a nondenominational pastor with a love for baseball. He played high school and junior college baseball and had high hopes for me to be a great baseball player, possibly the best since southpaw pitcher George Little Bird, who had made our town proud. I’m aware most of you know who George Little Bird is. His son is here locked up with the rest of us. I wasn’t a pitcher, but my father taught me how to throw a curveball and a fastball. He helped me lift weights in the garage and took me to the park down the street to throw baseballs at the backstop. I wanted to be a catcher, like Johnny Bench, but he insisted I try out for pitcher and stood on the mound with me every Saturday and after church on Sundays and some days after school, even in winter, showing me a good windup and form and reminding me of what I kept doing wrong. He would stand with his hands on his knees beside me as I pitched, his face swollen and pink from coughing his lungs out (he was a closet smoker but a heavy one, at least one or two packs every day), trying to distract me on purpose by making grunting noises during my windup because he said his distractions would help me block out other distractions, like crowds during games, which ultimately would make me a better pitcher. He made sure I threw with my right hand always, even though I’m technically left-handed. I’ve been ambidextrous thanks to him, able to write with either hand, bat left and right, and throw the ball especially hard with my right.

However, I had no interest in being a pitcher. On that cloudy day in the last light of a late afternoon winter, when I finally admitted this to him and said, “I don’t want to be a pitcher and I don’t even like baseball anymore,” my father kicked the dirt and sent me to the car, where I sat in the backseat and stared out the window while he lit a cigarette and collected the baseballs. His silence in the car on the drive home was expected, but when I was in bed that night in the darkness and my bedroom door opened and he entered, a tall, towering presence standing in the light from the hallway, he said he was grossly disappointed in me and saddened by my decision not to play baseball, and that there was no use going to the park anymore, what was the point, and that it had all been a goddamn waste of time, which on one hand pleased me but on the other hand his words “I’m grossly disappointed in you” ran through my head all night and for several days afterward, a moment that I would think about every night in bed for weeks, even months, and sometimes I thought about it at the dinner table when my father stabbed his meat with a look of weariness and regret instead of satisfaction and happiness. He was a man who kept to himself at the table, even at restaurants, rarely looking up from his plate, never conversing with my mother and certainly never with me, belching into his fist, staring watery-eyed at his food and chewing with a slow orgasmic intensity that appeared almost theatrical. I watched him eat this way for years. How is eating such a dead and lonely experience? After I told him I didn’t want to play baseball, he used his silence to dismiss me, not speaking to me for days. Even weeks. This was only a few years ago. When he finally spoke to me, he told me he didn’t care whether or not I chose to be left-handed. “The devil is a southpaw,” he told me. “He wants you to rebel against my wishes.”

I didn’t say anything for a while, and in the silence tried to figure out why he believed that. But I felt ashamed of myself, for not loving baseball, for not respecting him, and for disappointing him. My head felt dizzy every time I was around him after that, and I grew angrier and more hurt. I’m not worth much, I guess. I’m not trying to gain your sympathy, but right now I like this place better than I like living at home.

I’ll end by saying that even though many of you delinquents have done terrible things, I have done nothing that wasn’t in the name of justice, an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, and in fact all my good deeds would be way easier to list here than talking about my early memories of shame. For instance, I have tried to understand what it means to love and to be in love with someone, that loving a dog is no different from loving a person, and that with love comes obedience and discipline, which is to be learned if we are to love. Our elderly neighbors once owned a yellow dog. While they were at church on Sunday mornings, I would sneak into their yard and feed the dog, whose name was Honey, and she was a dog who loved honey, crackers, slices of bologna, and even plain bread, which I would keep in my coat pocket for her. Honey appreciated my gifts but growled at me sometimes, and I tried to teach her the importance of trust and affection in a private way without the elderly neighbors finding out.

Understand: soon enough, Honey accepted me, so do not ever say I’m not an empathetic, loving person the way I have loved animals, especially Honey (and later other dogs in my neighborhood), because I love those animals, I really do, I love them deeply, the way the python loves the pig under the deep red moon. ![]()

Brandon Hobson’s most recent novel is The Removed. He is the recipient of a 2022 Guggenheim Fellowship, and his novel Where the Dead Sit Talking was a finalist for the National Book Award, winner of the Reading the West Award, and longlisted for the Dublin Literary Award, among other distinctions. His short stories have won a Pushcart Prize and have appeared in The Best American Short Stories, McSweeney’s, Conjunctions, NOON, and elsewhere. He teaches creative writing at New Mexico State University and at the Institute of American Indian Arts, and he is the editor in chief of Puerto del Sol. He is an enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation tribe of Oklahoma.

“Letter to Residents” is an excerpt from a novel-in-progress.

Illustration: Josh Burwell