A little over a year ago, I moved to San Antonio. Since then, my mama has visited—often, and every time she parks her car at the door, there’s more of everything with her. More people. More bags. More plans. More requests of things like when can I wash and retwist her hair, or when am I gon’ write the book based off the plotline in her head, and mostly: where in the city can we go explore that got access to both kid-friendly activities and alcoholic beverages. Before I moved here, I lived with her in Dallas a lil over a year too. Spring of 2020. The pandemic hit the exact time my lease was up, and my mama had become the guardian of three little girls—my cousins. I decided to make my way back to Texas, finally, mostly because I assume my presence gon’ help since there’s no one else around who gon’ help her, like it’s my daughterly duty, even though I ain’t got no motherly instinct. Reacclimating to living with mine as an adult wasn’t that hard to do—albeit sometimes annoying, after not being there since I was eighteen. And living with three kids wasn’t that hard to do either—albeit sometimes annoying because they feed off each other’s energy considering they were only three, five, and seven at the time. Ironically, this was all happening while I was writing a memoir. I found it very hard to write, and hard to remember, reread, or remedy who I was at their ages. So during my homecoming, I spent all my time orchestrating bath routines, sitting through school days on Zoom, grocery shopping, cooking, playing, reading, picking up, dropping off, hosting movie and dance party nights—you know, parenting.

While living there, I stumbled upon a backstreet like an airplane runway that I would drive back and forth on endlessly whenever I needed to be alone. The road runs uninterrupted, and most people who live up against it own farms filled with cattle and small bodies of water. My mama’s house is blocks over and arm’s length from the next one, but it’s the longest she’s ever lived in the same spot my whole life. Six years. When I was a child, we lived up and down Interstate 635 in Mesquite, Garland, Forney, Pleasant Grove, and basically everywhere in Dallas. By the time I graduated high school, we had moved almost ten times due to rent changes or life changes, or a combination of both, so I never really saw home as a roof. There was never enough time to grow into anything, much less enough space to outgrow it. It was not home. It was a place where I slept. On couches, in her bed, on the floor. By the time I started looking to live on my own again, I hadn’t had a bed of my own in almost four years. Home for me has been a car and a road and sometimes getting back to wherever my mama was. But she’s settled now, and stable in her neighborhood—able to provide my lil cousins with a home, and I’m happy they got one. If there is a home of my own for me to have, I thought, I need to figure out where it’s at and who I am in it.

It’s like the more I attempted to write about my childhood, the more I realized my initial Dallas departure was outta desperation and not the pursuit of a college education. I spent too much time having the same conversation: the one where I try to make my mama understand how our family’s abuse of her kindness makes me start saying I don’t really love the people I’m supposed to. At least not in the way I’ve been conditioned to believe I should. I didn’t know how to explain that without people thinking I was loose in the membrane or trying to hurt somebody’s feelings. So I found other things to say.

I told my mama This what I be talking ’bout. When is you gon’ stop?

I told my mama They got a mama, bro.

I told my mama Don’t tell me ’bout they mama.

I told my mama I can’t take her mouth.

I told my mama You gon’ have to make a decision whether or not you gon’ keep them because letting her come in and out whenever she feel like it is doing more harm than good. If they gon’ be here, it’s your job to protect them.

I told my mama None of this would still be happening if you stuck to a boundary.

I swear, my original plan was to stay. In her house. For a year. And in Dallas, once I moved out.

I spent a month or two researching and touring apartments across the city while carrying out my cousin duties without complaint. I loved being with the kids. (I would love to be close enough to where they could visit me whenever they wanted, but that would never work.) I apartment hunted through Plano and Richardson and downtown Dallas in search of my first big girl apartment. But again, it was a constant reminder that there’s other places to go. I don’t know when flowers are supposed to bloom—all my plants are fake—but I know they ain’t on nobody’s road to be seen like they used to be. The bluebonnets that ran alongside every road in Ennis and even Lancaster done been replaced—or covered—by cement from dump trucks.

I drove up Interstate 30 east toward the “luxury” of standard amenities and west toward “extra fees” because in too many ways, the city is building itself into something it’s not. My plans no longer mattered once I realized the people in the neighborhoods I once roamed were getting kicked out of their lifelong homes to make room for high-rise apartments for tenants demanding off-leash hours for their dogs in designer clothes. I assumed my dislike of every layout was a metaphor for something, and that metaphor was: you stay here, you die here—on the inside. Plus, I was in a cloud all day, every day. That, and I was eating a lot of Chipotle. And all of it combined not only shifted the plan but messed with the writing. I was so worried about what was happening to the kids that it was hard to concentrate on myself. Plus, when my mama told me to leave it alone—that I worked myself up too much, as if she wasn’t the one who kept bringing me all the information—the panic attacks recommenced. I spent less time writing because I was mad—at her—mostly for allowing me to be her main source of support. Eventually I started telling her some harsher truths. And only then did she want me to be her child. I said, “Aight,” and looked out the window. If I was a kid, she would’ve said I was being disrespectful and made me turn to face her—stare at her—for the rest of the ride home. But I was grown and didn’t have to do anything. But I couldn’t stay, and it was no longer sad.

I said, “Aight,” and turned my back on it all.

I said, “Aight,” and tried to hold in the bubbles inside my body since we almost back at the house.

Once we were there, I said, “Aight,” and went in the back room. Told her I gotta write, but instead I heaved into an empty Chipotle bag under a blanket on the floor for thirty minutes straight about having to break up with my mama. Once my body stopped spasming, I kinda just stared in silence for a while before eating the Chipotle I’d set aside, and then I Googled an image of the Texas map. One thing I knew to be a fact: there’s a way to get anywhere, even away. I just picked a place, a place where I didn’t know nobody. Then I spent the rest of the afternoon making a list of apartments to tour.

It all happened overnight—I was out the door by five a.m. that morning with a friend who was tagging along for the adventure more than they were tryna convince me to stay.

“I understand that,” she said when I told her the story of how I had picked San Antonio. I didn’t know nothing ’bout it—had no ties to it—other than the few field trips in grade school, so this abrupt decision confused some folk. They asked, “You moving for a job?” I said no. They asked, “For love?” I said no. They said, “Well, can’t you just stay?” I said no. Once outta Dallas and on Interstate 35, we passed through Waco into Austin fairly quickly before entering New Braunfels, which I also knew nothing ’bout as a town other than going to Schlitterbahn once. I made great time. It was barely nine a.m. when we had to stop for gas—at Buc-ee’s—because everybody know that’s just what you do whenever you see one. And after hours of sitting and switching my music between alt sad Cali-girl and substance-abusing Atlanta rapper, I stood outside and pumped gas with one hand while holding an egg, bacon, and potato burrito in the other.

“You got a place you like the most?” my friend asked through the window while I bit into the burrito about forty-five minutes out. She knew if I was making the first step, I’d already overthought and planned a slew of outcomes.

“Yeah,” I said, chewing, shaking the gas nozzle free of its last drops, “the second one is where I wanna really live, I think.”

I knew a decision would be made that day. Out of the five SA spots I scouted, they were all nice, considering they didn’t look all that different from some of the Dallas apartments I had toured. There was usually a well-dressed lady with a fake smile telling us the building was new and the apartment’s appeal was that the building was new, yet something about it felt like a hotel. All the hallways were cold and excessively long; the bedrooms were boxy and small. I wouldn’t fit. We saw another apartment that was in my budget, but it reminded me too much of the time I had spent rooming with roaches in Alabama, so the answer was no. We even saw an apartment with a floor-to-ceiling glass sunroom attached, and it felt like something out of a movie, but it was way too expensive and way too close to Six Flags and US 281. And if I couldn’t get to Target whenever I wanted without a forty-five-minute delay, I didn’t think I could survive. The spot I mentioned at the gas station was also overpriced, but it was perfect because I wanted it. It was perfect because its size made sense. It had an extra room for activities (aka an office) I’d rarely use. A patio. Windows. Lots of windows, for the light I needed to let in. I figured if I was gon’ move for real, it was about time I loved where I stayed. Plus, I’d been doing ok at this adulting thing, and I didn’t give myself enough credit. I mean, my credit was kinda nonexistent and I didn’t even have a credit card, but still: I framed the decision as a reward to myself.

“Living here might be tight,” I said, although I’d already been emailing about submitting an application.

“Yeah, but you gotta take a risk,” my friend said. “Figure it out later.”

“Yea, you right.” I nodded once we were back in the car.

Looking out at the surroundings between apartment stops, I thought San Antonio seemed isolated enough. It was full of people, clearly. But as I drove into the city more, all I could think about was finding the longest road I could drive down. I spotted obscure roads and anticipated exploring them and it soothed me—the thought of all the windows down in the nighttime. “You right,” I said again, already plotting who I could become in this pending seclusion. It’s how I’d found all my empty roads. I had found the backstreet by my mama’s house because I was always searching. Some days I’d plan out what time of day I’d drive down it to feel the wind at its height, and sometimes I’d bring the kids along so they could hang their heads outta the window and watch the cows. Other days I’d just end up there whenever I needed to get out of the house. In the daytime, the road was usually hollow. At night—eerily calming, mostly because it was desolate and lacked streetlights. I’d drive to its edge just to turn around and go back the way I had come. I felt out of place everywhere I would land, probably because I was scared of everything. But driving down this backstreet revealed my desire to feel placed. Sturdy. Open to more than one dream—a place where I could take my time. A place where I wouldn’t always be fighting the desire to leave.

“Leaving ain’t gon’ do nothing, bro,” my friend said. “You still gon’ feel the same way because you care about them kids, and you care about how people treat yo mama. You really all she got.” I didn’t agree about the leaving part because I hadn’t fully accepted maybe I was a runner, but I got what she saying. “I already know how you is though,” she finished. “Bye.” She laughed. “I’ll see you in six months. I’ll come visit.”

Two and a half months after that trip, I was living in San Antonio. Originally, I thought the move was the breakup and all it would take is a toll tag and a seventy-five-mile-per-hour speed limit. Something like that. But I was always speeding then. The three years I lived in Alabama, I drove nine hours back home to Dallas as often as I could to get away from my depression. When I moved back in with my mama, I’d drive around aimlessly for hours to get away from my anger. When I drove around the city limits of San Antonio, I realized this city was also changing into something big-city adjacent with all its pending construction, fusion taco spots, and Starbucks on every corner. But it didn’t bother me, because it wasn’t about the place—it was about how I felt in the space. I changed cities with nothing but boxes of books and some clothes, and yet I never felt as content as I did with myself in a half-empty apartment. I loved figuring out what I wanted to do in each room of my space, where I was the most comfortable and safe I’d ever felt in my body.

My mama and my lil cousins helped me move in, and when she left, she texted me: in line at Starbucks which I will probably stop drinking so much of once we get back home. Speaking of home, make yours what you want and need it to be. In this same text, she also said: Keep in mind—family is forever and when we get to heaven it will be more of us. I finally accepted that she will never get it, or me.

I worked on my book nonstop from the moment I moved in, and almost eight months later, it was finally formed into a shape I wasn’t too ashamed to share. And although working on the book was the most devastating and stressful process I’ve ever endured, working on it made me fearless. Working on me is how I got here in the first place.

Now, I am alone. Even my dog is dead. I don’t know a better way to put it. I’m not complaining; this is the exact way I like it, the exact way I’ve always wanted it. I love not knowing nobody in this city. At a year of living here, I’ve stopped feeling unsettled, because I’ve stopped excusing my inability to face myself for freedom. This is the proudest I’ve ever been of me, even when it hurts. Even in those moments where my existence feels overwhelming, I don’t get the urge to run. Or throw up. I just lie down. In my bed. And say thank you. ![]()

Kendra Allen was born and raised in Dallas, Texas. She loves laughing, leaving, and writing Make Love in My Car, a music column for Southwest Review. Some of her other work can be found in, or on, the Paris Review, High Times, the Rumpus, and more. She’s the author of a book of poetry, The Collection Plate, and a book of essays, When You Learn the Alphabet, which won the 2018 Iowa Prize for Literary Nonfiction. Fruit Punch, her memoir, is out now.

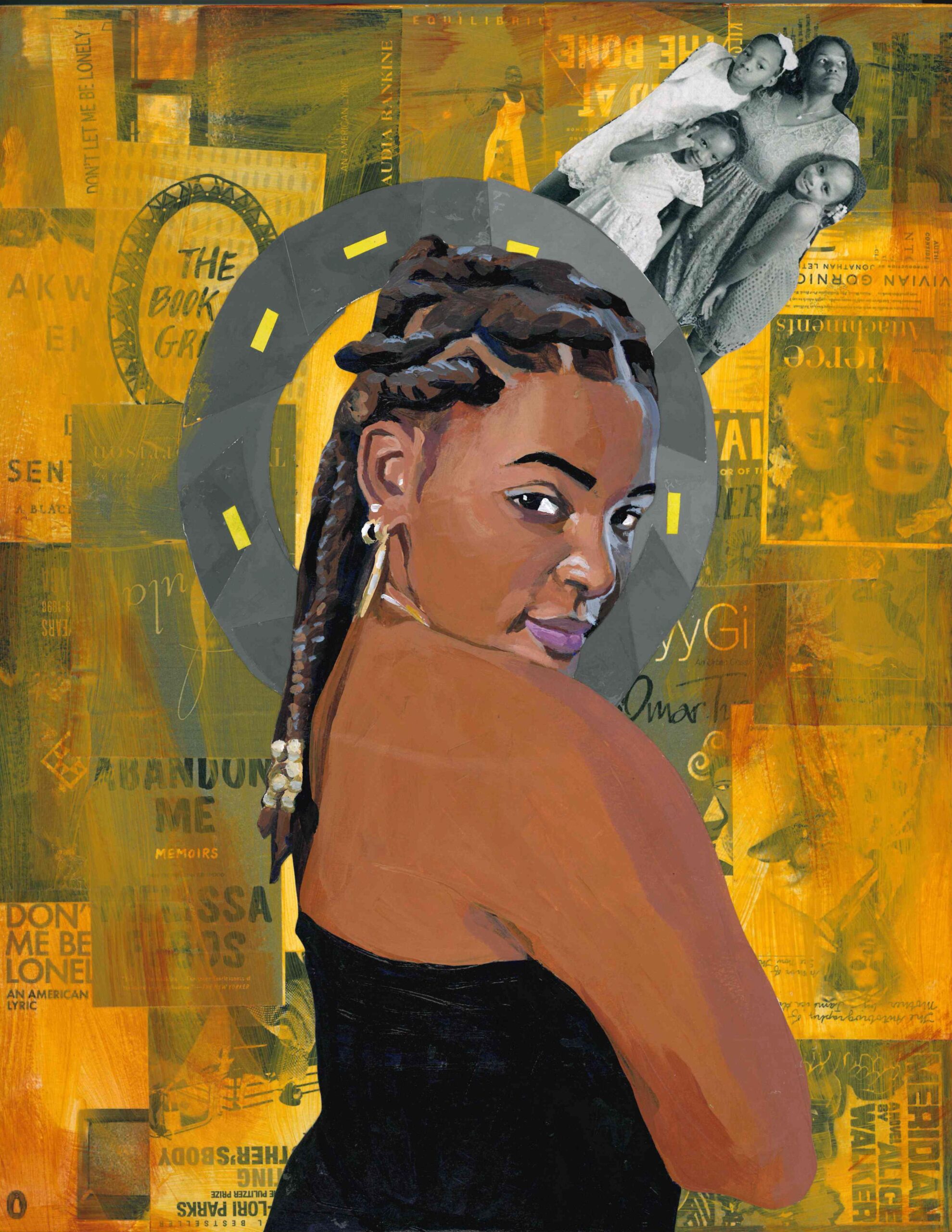

Illustration: Vitus Shell