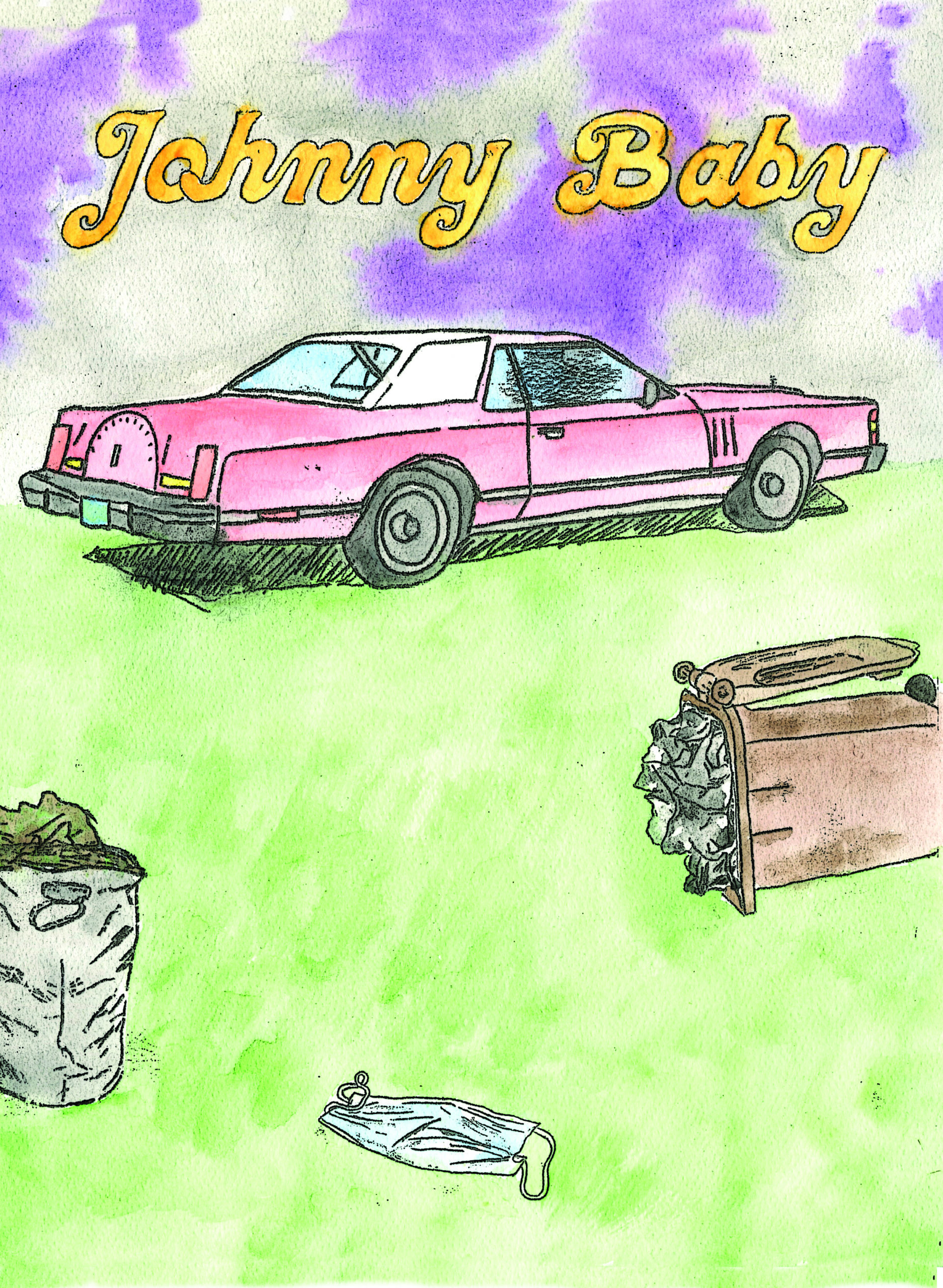

Johnny-baby lies to everybody in Los Angeles County jail.

Goons, bluhs, cuzzos, honeys, angels, bitch-asses, body snatchers, peckerwoods, and palm tree thieves.

Cell to cell, for hours, and days, through transfers and bureaucratic tedium—Johnny rewrites the story of his arrest.

The lie gets sharp as a shiv. A narrative to stick in prisoners who want to make Johnny a punk. Outside, Johnny calls himself a punk. In here he can’t be one.

Johnny-baby sits scheming, not speaking unless spoken to, on a bench between a guy who was supposed to be an NBA shooting guard but shot someone, and a guy who is “totally and completely innocent.”

Johnny is surprised so many of the men in County jail are definitely not guilty. Say, “Wasn’t me.”

But guilt is a feeling as much as a verdict. Poets like Goethe and Johnny-baby know that two souls dwell in the human breast: the self and what is inside, repressed.

The shooting guard asks, because everybody asks, why Johnny was arrested. The lie is ready. The best lies are truths. The truth is, Johnny-baby really does want to defund the police, economic equality, and no prisons. But a lie is also very different from the truth. Johnny-baby no longer tells the truth-truth. The stupid, stupid, totally stupid truth about why he was arrested. His hippy ex-girlfriend. Subsequently, his cellmates no longer laugh and call him: dumbfuck, dumbass-whiteboy, and puta.

“Little white-ass redhead,” the shooting guard says, loud enough for the whole cell, “outside protesting for Black lives.”

The white-ass is Johnny-baby. He wasn’t exactly protesting for Black lives, but even so.

Someone says, “Respect.” Which means Johnny has it.

Johnny hopes respect will insulate him from the violence in County. Violence is like the cold air pumped into the cell. It keeps everything alive.

Someone coughs.

Someone says, “Motherfucker, shut your mouth, I ain’t tell you again.”

There’s a superbug. But no masks.

“Bullshit,” someone says.

“Death sentence,” someone says.

“Business as usual,” someone says.

![]()

Yesterday, Johnny was on the prestige-green lawn of a research university. Zip stripped, spread-eagle, and face down with his fellow protesters. Skinny-wristed kids, picked up and pushed onto a police bus. Johnny could hear the baying of the laboratory dogs being returned to their cages.

In City jail, Johnny was given a sandwich. He took off the cheese. It was all cheese. In mugshots he said cheese and showed his tongue.

In solidarity, Johnny refused to give his name, so was booked as John Doe 13.

Cool.

In their jail cell, Johnny and the protesters kumbaya’d through the night and in the morning vinyasa’d to greet the sun. Johnny daydreamed of his hippy ex-girlfriend and the stories he would tell her through social media posts about his incarceration as a political prisoner. Not only did he say “Solidarity!”—he felt it. Then he felt alone, as one by one his fellow protesters were set free, or sent somewhere Johnny couldn’t go. Into his solitude entered the sheriffs, who transferred Johnny from City to County.

![]()

“Shoes off,” the County sheriffs say, and search among the men for the largest and smallest shoes.

“Dance,” the sheriffs say, and the squat Guatemalan does, forced to wear the shooting guard’s enormous Nikes.

“La Cucaracha” the sheriffs whistle.

Johnny-baby and the men stop laughing when the sheriffs say, “Strip.” Not laughing when the sheriffs shine a flashlight where the sun doesn’t. On command Johnny coughs to check if contraband comes out.

The sheriffs say the guy who is “totally and completely innocent” was arrested with his girlfriend dead in the trunk. Except she wasn’t actually dead. Only the baby was. To Johnny-baby it sounds like the sheriffs expect something will be done about it in the showers.

If the season was spring instead of summer, Johnny would with boys be in juvie, under the warming jets, washing with delousing soap. But as it is, Johnny tries not to look like he’s looking in the showers with the men.

“I know you?” a man says.

Johnny-baby wonders whether he needs to make a power move for clout. Pick a fight with someone big. But not too.

Johnny has had fights, though he’s no good at them. He pretends to be a pacifist around his peace punk friends, then watches big fights with his father who pays for pay-per-view violence. Except, lately, Johnny and his father—the chicken-hawk, capitalist, cowboys-don’t-cry conservative—do the fighting. Johnny blames his father for almost everything. Except abandoning Johnny’s mother. Johnny would do that too if he could.

Dripping wet from the shower, Johnny is issued slip-on shoes, boxer shorts, and a sloppy suit of jail blues. The bottoms are blue and baggy like Johnny’s mother wears. Even on her infrequent outings outside their apartment, she wears saggy sweatpants made for XL men.

“You look like shit,” Johnny sometimes says, and refuses to drive her to the pharmacy to pick up her prescriptions.

Does Johnny feel guilty for making his mother cry? Yes, of course, but he’s ashamed of her and feels she should be ashamed too.

Some of the prisoners wear yellow bottoms. You don’t want to be seen talking to yellow bottoms, Johnny learns, after he does.

The reason returns Johnny to his mother, her rationale, rooted in girlhood, for wearing bottoms sexlessly. But it’s not safe to think of his mother here. Unsafe to be a boy among men. Men in yellow bottoms.

Johnny wishes he could phone his mother and say, “Mommy, I’m sorry.”

If the sheriffs ask again, this time will be different, and Johnny will definitely say, “Yes, I do want to make a phone call.”

Johnny-baby is busy belittling himself for adding to the suffering of his mother when the sheriffs come to segregate the prisoners by color. Bottoms and skin. Yellow and blue. Brown and White. Black and everyone else somewhere else.

The sheriffs say Johnny-baby’s permanent cell is a dayroom, but due to overcrowding it’s an “all day, every day” room. The bored men who populate the dayroom play cards, sleep, and crowd Johnny asking questions about why he’s in County jail.

“You don’t belong in here, niño. An old cholo like me can tell.”

“Nah,” Johnny says, preparing the lie.

Since the segregation, Johnny-baby has stopped saying BLM because some of the men ask, “What about Brown lives, we don’t matter?” The men have nothing but time, but they have short attention spans, and as a white-ass Johnny understands he can’t teach them anything about racism that they don’t already know. Johnny has also stopped saying abolish prisons because the prisoners think it’s a bad idea.

Instead Johnny says, “I was protesting mandatory minimum sentencing,” because he’s learned that many of the men are up against it. The old cholo is. The old cholo is on loan from Folsom. The old cholo is awaiting a court appearance for his third felony, which means twenty-five years to life. In the dayroom, three felonies is like being the hero of three wars, and the old cholo moves among the men like he has medals on his chest.

“. . . and the death penalty,” Johnny adds, because he wants to be a hero too.

“You a down-ass peckerwood,” the old cholo says, and offers Johnny-baby the top bunk.

Johnny lies back on the bunk and uses his hands for a pillow. He isn’t exactly sure what a peckerwood is, except that it’s him.

“You’re different, niño,” the old cholo says, and rests his arm on Johnny’s mattress. “I’m different too.”

Johnny thinks the old cholo is very old, probably forty years old, but strong, with the square shoulders of a boxer.

“I was born in Mexico City,” the old cholo says. “Not this peen-cheh city. Remember that.”

Johnny thinks the old cholo looks like the boxer Antonio Margarito, an infamous cheat who fought with cement in his gloves.

“My father’s family are royalty,” the old cholo says. “Emperor Maximiliano, you know him?”

Johnny knows from art history. Manet. The Execution of Emperor Maximiliano.

“Of course you do. You’re smart, niño.”

Johnny-baby doesn’t like being called niño.

“Don’t worry, niño,” the old cholo says, and sweeps his hand across Johnny’s mattress, and the sweeping motion continues into the air, and seems to sweep away everyone . . . “For what you did in the streets” . . . sweeping away the men playing poker for push-ups . . . “I preeciate you” . . . sweeping away the toilet, which Johnny needs to use, where a man lathers the scalp of another man, dragging the razor straight, the way you have to shave, erasing, wiping away everything . . . “In here, niño, I’ll take care of you.”

Dinner comes on a tray and Johnny crawls down from his bunk trying not to look squirrelly. As a vegan he’s learned not to expect to eat. He pokes his spork into stalks of soft-boiled broccoli. Considers the macaroni and cheese. Sips his juice box.

To the men at the table, he offers his brownie. Even as he says it, he regrets it. The old cholo smiles as he bites it.

The old cholo wears blue bottoms, not yellow, but Johnny knows it was a mistake to give up his brownie.

“Gracias, niño.”

After dinner Johnny-baby lies on his bunk and pretends to read a book. The only book in the dayroom. The one book he swore never to read. It’s a dumbed-down version with the big and interesting words truncated. Still, the book is substantial. Johnny closes his eyes and dreams of using the weight of the word of God against the old brownie-eating cholo—

Thmp. Thmp. Thmp. Thwack. Thwack. Thmp.

![]()

Johnny-baby wakes with the name of the Lord in his mouth, and a cramp in his tummy. He crawls off the bunk like something arboreal, careful not to disturb the snoring old cholo. Johnny scurries across the dark dayroom, clenching, cursing the macaroni and cheese, as well as his mother for a hereditary intolerance to lactose.

On the toilet, Johnny-baby sits in contemplation, doing nothing, just listening to his own unfortunate noises. He stares out at the immense darkness of the dayroom—and at something large moving slowly across the floor. Johnny squints. The thing on the floor continues to crawl toward Johnny on the toilet. Johnny lifts a leg out of his baggy bottoms, readying himself to run.

The thing lets out a desolate little sob.

Johnny knows the thing on the floor is a person, not a thing, but decides it’s safer to think of it as a thing.

The thing’s eyes, white as milk, rise to meet Johnny’s.

“Whas up,” the thing whispers.

Johnny lets out a big one.

“My bad,” the thing says.

Johnny is this close to wiping, flushing, and walking away—but the thing crawls into a ray of LED light that illuminates its red hair.

“What happened to you?” Johnny says, to this redhead on the floor whose face is badly busted.

“Don’t call nobody,” it says.

Johnny wasn’t going to.

“I’m Eddie.” The thing coughs. “They call me Twenty.”

Johnny doesn’t like the sound of it.

Twenty coughs again. “You keep a secret?”

Johnny thinks of his own secret. All his lies.

Twenty’s smile is white, brace-straight, but it’s his red hair that makes Johnny want to trust. Johnny knows firsthand the stigma of being born with red hair. Recently Johnny read that in religious paintings, Judas is often depicted with red hair to make the traitor pop on the canvas among the other apostles of Jesus. Johnny believes this painterly trick has caused centuries of negativity toward redheads.

“Real talk,” Twenty says. “Sheriffs sayin I be slanging yayo to kiddies.”

“They what?” Johnny says, suddenly worried about what the sheriffs might say about his own arrest.

“Bunch a bitch-asses in my mod merked me. But I ain’t even. Like how old is you, Johnny?”

Johnny says.

“That’s what I’m sayin, my customers, same age as us, bruh.”

According to Twenty, drugs should be legal, and the government has no right to tell anyone what to do with their body. He says the war on drugs criminalizes poor people. Johnny wants to add that people of color have it especially bad, but Twenty has already moved on to telling Johnny about essential aspects of morality, theology, and botany. Usually he starts with “Listen” and ends with “think about it.” For example, “Listen Johnny, cocaine is made by God, shit literally grows out the soil, so can’t be bad, think about it.”

Johnny hates when people talk like this.

He doesn’t think Twenty’s crime is serious enough to grant him so much wisdom. In fact, at Johnny’s high school, he was the number two biggest supplier of LSD until his father sent him to rehab, where he met the hippy girl.

“What you in for, Johnny-baby?”

The hippy girl. She had shown him so many injustices.

“What?” Twenty says.

“Oh . . .” Johnny says. “Protesting the war on drugs.”

“Thas whas up.”

Does Johnny feel guilty for lying to Twenty? Maybe. But Johnny needs an ally.

Johnny helps Twenty up to an empty bunk. Boosts him to the top.

“G’night,” Twenty says, and rolls to face the wall.

“Goodnight,” Johnny says, lingering at the foot.

![]()

Through the long night, Johnny’s dreams are troubled by visits from his hippy ex-girlfriend, who made him promise never to use her name in the poems he wrote for his community college classes. In the dream Johnny says what he did for the laboratory animals was also for her, but she simply walks away from him, holding the hand of the trans-rights activist that she dumped Johnny for during her first semester at the university.

In the morning, the dayroom is different. Twenty struts shirtless, slapping hands with his cellmates, forming relationships. Is Twenty ignoring Johnny-baby? When the eyes of the two boys finally meet, they both quickly look away.

For most of the morning, Johnny lies on his bunk and watches Twenty peacock, smooth chest puffed like a super featherweight. Johnny squints, trying to read the cursive on Twenty’s breast, the blue ink, bold on his cadaverous whiteness: Chris.

There is another person in Twenty’s life. That other person has a name. Their name is Chris.

Johnny considers his own body, unmarked, unremarkable, unnamed, and feels ashamed of its cleanliness. He won’t even allow himself to write her name in a poem.

“Yo, Johnny-baby,” Twenty says.

Johnny sits upright, grateful to Twenty for remembering.

“We about to shave these noggins.” Twenty ruffles his own red hair. “Let’s go!”

A bald man at the toilet waves a razor, “Ándale, pelo rojo.”

Twenty walks backward, pointing at Johnny, “You next, dawg.”

Johnny wants to join, to show solidarity, and not feel so alone.

“Don’t do it, niño,” the old cholo says, from the bottom bunk. “Don’t be going in front of no judge, looking like a pelon.”

The word sounds like felon, but means “penis.”

The old cholo rolls out of bed. Johnny reaches for the Bible he’s been using as a pillow.

“You go to court looking like a convict,” the old cholo says, “that’s what the jury gonna do, con–vict.”

From Johnny’s perch on the top bunk, he watches the old cholo and the other men gather at the toilet to witness the shaving of Twenty. Every man in the dayroom—except the DUI with the rough cough, who will get his ass beat if he leaves his bunk again—congregates at the toilet to see the razor scrape across Twenty’s scalp.

There’s no more soap. No hand-washing.

“Yo,” Twenty says, and wipes the blood from his eyes. “Easy, ese.”

Tufts of red hair fall over the laughter of men.

KA-KLNG-KLNG. Heads turn to the door. The sheriffs shove a scabby, sunburned thing into the dayroom.

It’s a thing Johnny recognizes. The thing whose crime of stealing a palm tree—felony theft, his third felony, potentially twenty-five years to life—gave Johnny the original idea to lie. Don’t tell the stupid, stupid, totally stupid truth. But only after Johnny did, did he learn not to. The sunburned palm tree thief knows Johnny’s truth. A truth as stupid as stealing a palm tree. Maybe more. Yes, more. Love is the most stupid truth.

Johnny-baby is wondering what will happen when his cellmates learn the truth—

“John Doe 13,” the sheriff says.

The junky palm tree thief smiles at Johnny.

![]()

The sheriffs put a mask on Johnny-baby because of the superbug. Put him in a short bus. Out the window he watches traffic on the freeway heading south toward the suburb where he lives with his mother. The bus stops downtown at the criminal court building.

“Two felonies,” says his court-appointed lawyer. Loose necktie, brown loafers with worn-out soles. “Felony vandalism. Felony inciting a riot.”

Johnny doesn’t like his lawyer’s negativity. He wants the old white-ass to treat him like a son.

The sheriffs lead Johnny-baby handcuffed into the courtroom. At first he doesn’t recognize his own mother: standing, waving, in a mask and dress. No baggy bottoms. The dress, floral as a Fantin-Latour painting. The dress, it’s roses, thorny in Johnny’s throat.

But where is Johnny’s father? No, of course his father isn’t here. Stupid of Johnny. Dumb, Johnny. Johnny is busy feeling like a dum-dum and barely hears the date of his trial. His bail. An impossible amount. The judge’s gavel.

![]()

Johnny-baby does push-ups. Sit-ups. Shadowboxes in his holding cell, preparing for what awaits him in the dayroom—the palm tree thief, the old cholo, and his other self.

But before the dayroom, there is the routine bureaucratic tedium of County. The boredom of being transferred, cell to cell, hour after hour. His fellow prisoners sigh, rap freestyle, fart, blame someone else, do jumping jacks to stay warm.

Finally, after midnight, Johnny is moved to a cell where a man says, “First thing I’ma do is feed my dog. Just, you know, watch her eat with thankfulness.”

The other men in the cell say what they will do. Who. What positions.

The men are being released. Johnny is among the men. Bail is posted. Johnny is pulling on the legs of his Levi’s. He is walking fast through the corridor, forcing himself not to run. Not running with the other men through the security doors and into the night.

Johnny glances back at the jail. Sensing he shouldn’t. That he should never look back. What had happened in the jail? Had Johnny really . . . Had he . . .

He is walking on the sidewalk through the crowd of recently freed men, baby mamas, and babies. Johnny hears tribal drums and sees protesters, dogs on ropes, under the light of a streetlamp. He wonders where he is in the city.

“John.”

What had Twenty called him? Johnny-baby.

Again—“John.”

And there is his father.

Johnny takes a step in the direction of the protesters, the drumming, and the hand-painted signs. But then his father is hugging him. And the hug feels inescapable. And he doesn’t want to be released.

Johnny is climbing into the passenger seat of his father’s car, moving aside the sleeping bag his father used while camping in the parking lot awaiting Johnny’s bail bond. The vegan food in the Styrofoam box is cold and day-old, but so good Johnny licks his fingers. Johnny lied to Twenty, lied to the men, and left them all behind. He would never go back. He would go back every day. Would he ever escape the lies.

In his father’s car, merging onto the freeway headed toward the suburbs, Johnny wonders what has changed. The lights of downtown Los Angeles appear the same amount of beautiful. He looks at his father. Older. Somewhat smaller. His father looks at him and transmits something silent. Something that passes through Johnny, who feels that he is, finally, truly seen.

“What were you thinking, dummy?” his father says.

Johnny turns toward the window and coughs, and the cough fogs the glass, obscuring anything beyond. ![]()

Jon Lindsey is the author of the novel Body High. His writing has appeared in NY Tyrant Magazine, Muumuu House, and Forever Magazine. He lives in Los Angeles.

Illustration: Josh Burwell