Come on Down, It’s Not that Weird | A Conversation with Michael Bible

Interviews

By Ashleigh Bryant Phillips

It’s hard to hear the South anymore unless you’re in a small Southern town or some rural Southern outpost. The Southern accent is dying out. I can tell you this because I’m from a real small town in North Carolina and I’ve been to plenty larger Southern towns and cities where folks don’t really have accents.

A couple of years ago I found myself in Pittsburgh meeting up with some writers from New York City to do a lil Appalachian reading tour. I met the New York City writers at a crowded Italian dive bar called Nico’s. One of them places where you can still smoke inside. And there, ringing clear as a bell, cutting through all the noise, was the sound of back home, the sound of North Carolina and I couldn’t help it, I was instantly drawn in. It was Michael Bible. He was wearing a cap that had the brand name of some kind of fishing lure my daddy used. The next day as we weaved in and around mountains, Bible blasted early Tim McGraw hits, singing them, not missing a beat, he knew every song by heart. But Bible also praised the wonders of New York City, how he ain’t nothing but a subway ride away from three thousand years of culture. It blew my mind, how could a good ole Southern boy like him exist and thrive in New York Fucking City?

“When you get home, you have to read The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter,” Bible said.

So I did and that’s when it all made sense. The alienation of Mick Kelly, obsessed with classical symphonies to the point of tears and not being able to talk to anyone in her small Southern town about it—Mick was interested in so much more than her place could offer. I felt like that growing up. Bible must have recognized it when he met me, because that’s how he felt growing up in the South too.

The more I learned about Bible and McCullers, the more cosmic everything became. Bible was born on Fort Bragg in North Carolina, where McCullers lived for a time. But after leaving her hometown in Georgia, McCullers mostly lived the rest of her life (and died) in New York. Michael Bible was raised in the small town of Statesville, North Carolina. But after school in Tennessee and Mississippi, Bible too, like Carson, left the South for bigger cities. Bible lived in L.A. before landing in New York. But despite leaving their small Southern towns, both McCullers and Bible retained their accents, you can hear the South in their voices but maybe more importantly you can hear it in their work. You see, both McCullers and Bible only write Southern stories, place-based novels about the tiny towns they longed to leave. Forever haunted.

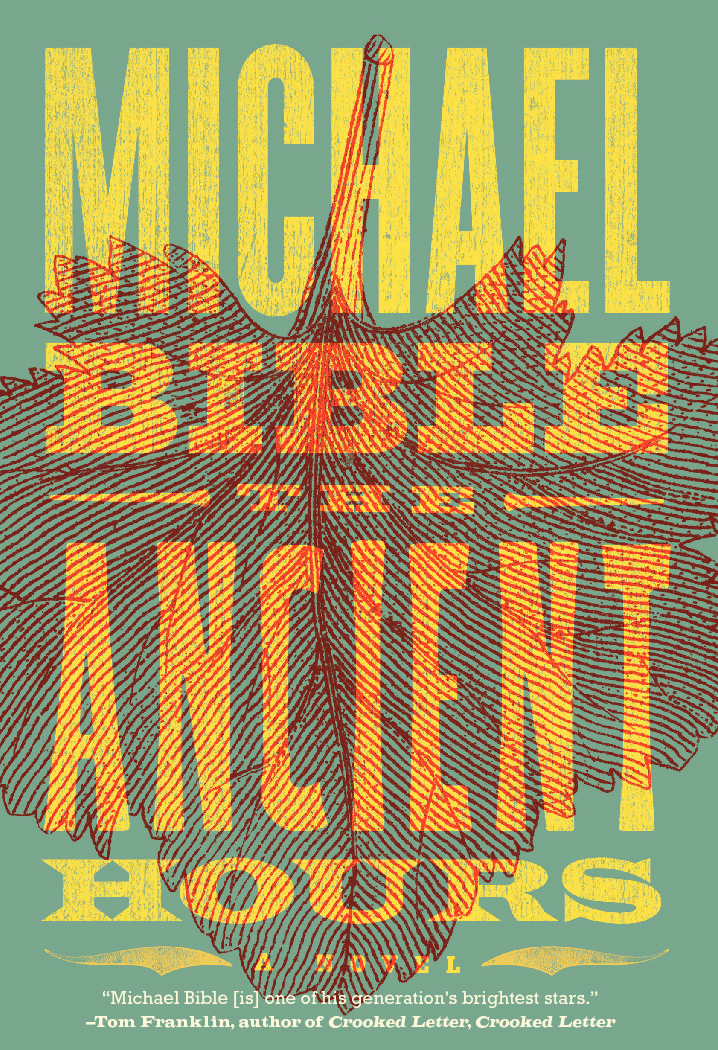

Bible’s latest novel, The Ancient Hours, is told at various times and from various points of view. You hear from the folks of Harmony, North Carolina, after a teen boy lights a church on fire and twenty-five people are killed. Basically how do you alleviate getting eaten away by loneliness and discontent, trauma and hurt? This is a question McCullers explored in her work. But here, Bible gives us a modern novel with his own genius. There’s a prophet, a love triangle, a busking saxophonist, a thesis on Paradise Lost, a whole community grieving. I’ve never read a novel as gracefully disjointed and perfectly imbalanced as The Ancient Hours, one that truly sounds like home:

“Out of the clear blue Joe asked if Trudy would sit next to him at church.”

Bible knows how to write a sentence like that because he’s heard sentences like that his whole life. He even speaks like that himself. I figure that makes Bible one of our last Southern writers.

Anyways, I read The Ancient Hours in two sittings. And then afterwards I sat there and thought, “Damn—how did he do that?” Then I closed my eyes and the first thing I saw was the work of Helen Frankenthaler.

So I called Bible up on his landline phone in New York City one night to tell him how much I loved The Ancient Hours and how he ought to be so proud of it. But also, I needed to ask him if he knew Helen Frankenthaler. And as it goes with Southerners, especially ones that were deprived of outside art and culture for most of their growing-up lives, me and Bible ended up on the phone for two hours talking about all sorts of things. Maybe you’ll find some of it interesting?

Either way, I can tell you right now Michael Bible is one of the best writers alive, not just for the South but for the world. The Ancient Hours looks like this to me:

Maybe listen to Tim McGraw’s debut album while you read this. Back to the phone call . . .

Ashleigh Bryant Phillips: Do you know Helen Frankenthaler? She painted these big canvases with sweeps of color. And there’s no real rhyme or reason to the patterns or what’s going on but looking at it all together makes sense and it’s just so beautiful. Anyways, that’s what I felt with The Ancient Hours.

Michael Bible: I think it’s interesting that you saw an expressionistic painting in it because I’m a huge fan of that type of work. I’m not as familiar with Helen Frankenthaler, but I’m certainly familiar with her contemporaries like Lee Krasner or Milton Avery. Milton Avery was one of Mark Rothko’s teachers and he’s right in that period before painting becomes pure abstraction. There are still some figurative things in there. I was an English major with an art history minor in college. I always liked minimalism in art because if you take away all the representational stuff, it becomes about the organic process of the basics. Color, size, shape, texture. That’s what makes a minimalist sculpture. The same is true for Milton Avery. When you strip away those figurative ideas, color becomes so much more important. Brushstrokes, shapes, and sizes start to matter more. You can still kinda see something in it, but it’s not a traditional thing you’re looking for. It reminds me of when I was a kid in preschool. I was trying to draw a tree and I was terrible. I couldn’t get a tree, I couldn’t get a cat, I couldn’t get a house. It all looked terrible. And my preschool teacher told me, “You know, you don’t have to draw what you see—you can also draw how you feel.” My takeaway from this was scribble whatever you want and then find the house, the cat, the tree in the abstraction. That’s similar to the process of how I tried to write The Ancient Hours. So what you said is exactly how I envisioned it.

Another thing, and I didn’t intend this as I was writing it, but the structure of this book is also like The Gospels.

ABP: I mean, being from small-town Statesville, North Carolina, you were probably forced to come up in a church, right? So hearing all that preaching and all those years in Sunday school are bound to come out in some way. Makes sense!

MB: Exactly. The Ancient Hours is sort of the same story told from four different perspectives, four different ways. Almost as if each section had a different intended audience but talking about the same subject.

ABP: I’m also a big cult person, so I was tickled to see one of the characters in The Ancient Hours get involved in one. Do you have any favorite cults?

MB: So, my mom is in this group of women called the Roosters. Sometimes she’d say, “The Roosters are gonna go up to The Yellow Cafe, if y’all want to come with us.” And I’d be like, “What is The Yellow Cafe?” And she’d say, “This restaurant up in Wilkes County—it’s organic, you’re gonna love it.” I looked it up and I was like, “Oh, this is a cult.” The cult came out of this weird 60s hippie sect of Christianity. In order to join, you have to give them all your money and live and work in this commune, and part of the commune is this restaurant.

ABP: Lord have mercy.

MB: So that was the basis of the cult in the novel, The Yellow Children of God. But there’s another part too . . . did I ever tell you that I went to the Dylann Roof trial?

ABP: Oh wow, no.

MB: Well I went down there to cover it for a magazine, but I’d been interested in the story before I even got the assignment. The story I wrote never got published, but I came across the best piece of journalism I’ve probably ever read in my life. It reads like a painfully beautiful short story. It’s called “American Void,” and it came out in The Washington Post not long after the Charleston massacre. A journalist had gone to the trailer where Dylann Roof was living in the days leading up to the massacre, and she wrote about the people that he was living with. What’s revealed in the article is that Dylann Roof’s roommates basically could have stopped him. At one point he got really drunk and explained to them what he was going to do, that he was going to shoot all these people. His friends hid his gun, and the next day, when everyone was sobered up, his friends thought, “Oh he was just playing around last night.” So they gave the gun back to him. The characters and the place and the stakes of that story really got to me. This was at a time when there were so many shootings, it felt like there was one a day. So I started thinking about what would happen to a town years after a massacre like that happened. How a casual incident—like giving the gun back to him—could change everything. And all the things that could have stopped this from happening and yet didn’t. What would happen to the people? I thought about writing a nonfiction book, but that didn’t feel right. Then these fictional characters started to appear, and it became The Ancient Hours.

ABP: I’m so glad the novel ended up being told the way it did, by the people of Harmony, North Carolina. Those characters there are good storytellers! Reminds me of something Mary Hood said about Southern identity. Mary Hood was a Georgian (as in the state) short story writer. Anyways I’m gonna paraphrase it. Basically if somebody is walking across a field and somebody says, “Who’s that?,” a Southerner would say something like, “Oh that’s Shelia. Her daddy’s the one that got struck dead by lightning on the river bridge. Was in the water a long time before they found the body. Then Jeffrey who lives down the curve there caught a catfish and found Shelia’s daddy’s watch in that catfish stomach. Shelia took that watch to show-and-tell for forever.” Whereas a non-Southerner would say, “That’s Shelia Brown.” To which the Southerner would say, “They didn’t ask her name, they asked who she is!”

MB: The person is a story rather than an “integer in a criminal economy,” as James Agee wrote in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. People are human beings, and there’s an actual recognition of that in the South. And because there’s that familiarity, there’s more acceptance.

ABP: What was it like when you moved out of the South, to L.A. and New York?

MB: When I moved to L.A., I tended to find other Southerners. And in New York I find myself drifting toward them too. I don’t know how many times this has happened to me . . . two weeks ago I was in Brooklyn seeing a friend and we were eating a slice of pizza and this guy from Georgia walked up and sat down with us. As soon as I found out he went to school in Athens, I asked if he knew someone I knew down there and turned out we knew a lot of the same people.

I love living in New York. I’m within walking distance of great bookstores and movie theaters. Any day of the week, I can go see a writer or musician that I admire. But the culture can be saturating too. After you’ve been here a while, you stop going to all that stuff because it’s always there.

But in the South, we don’t have that. So we tend to find entertainment in each other. So whether or not you have a funny story is the entertainment. That’s what passes as the museum or concert or whatever. When I was a child in the 80s, I remember going to Alabama to see my grandparents and I’ve never laughed that hard in my life. They’re smoking and drinking at the table after dinner and my grandfather and dad are roasting each other. Everyone’s telling stories like “You’re not gonna believe this one” and doing impressions. I know every region has some version of that, but in the South we’ve refined it to an art form. I’m always more interested in those kinds of people rather than the people who are celebrated in our culture. The people who are being themselves and have nothing to lose and just don’t care—they’re the real ones.

ABP: Yes, the real ones. I’mma switch gears here. Have you ever had Georgian wine? Like from Georgia, the country?

MB: No, but tell me more.

ABP: Georgia, the country, has some of the oldest grape varietals in the world, and it’s believed to be the birthplace of winemaking. Every lil rural village has their special grape and some old men who make these huge terracotta pots, so big you can stand in them. So they make these terracotta pots and fill them up with their special grapes and then bury the pots underground to ferment. No other wine in the world tastes like it.

MB: Sounds amazing.

ABP: And then when they drink the wine, they sing these old polyphonic a cappella songs. Anyways, after I learned about Georgian wine, my boyfriend gave me this short story collection by a Georgian writer. She’s from Tbilisi, the capital. And her stories are incredible. They sound like some stranger you’ve never met just telling you the craziest shit. They’re so voice-driven and alive and honest and real. And if they were workshopped over here in America, folks would say, “These aren’t short stories.” But what I love about them is that they’re so authentically of place, of Tbilisi, of Georgia. And even though I don’t know Sam Hill about Georgia, I know these stories are real. I can feel them.

MB: What’s this writer’s name?

ABP: I’m not going to say it because I’m going to butcher it to hell, but I’ll email it to you later.

MB: Yes, please do. Isn’t that great though? There’s a real power in art, crossing divides like that. And when we talk about place and the South, that’s what I hope to do. Because I’ve encountered people who say, “Why would I want to go down there?” And I get that. But I hope that my work can build a bridge that says, “This is a way in.” It’s sad that even within our own country we can’t bridge the divides. Jesus Christ, come on down and eat at the Waffle House—it’s great! It’s not that weird!

ABP: Hell yeah. Now look, I’ve been wondering about this since I met you, but I’ve never asked. Is Bible your real name?

MB: It’s my mom’s maiden name. I use that name because I was very close to my mom’s dad and he had two daughters so the Bible name would have died because they’re weren’t any boys. Also it’s just weird. I went with my family a couple of years ago to this old graveyard and found out that many Bibles were proudly Southern but also fiercely anti-Confederacy. They fought for the Union. It’s an interesting story, that there are pockets of resistance within the main narrative. The South isn’t an ideologically flat region.

ABP: People love to make it that though, especially folks who make them shirts that say KISS MY GRITS. There’s another thing I’ve always wanted to talk to you about and then I’mma let you go. I want to talk about Carson McCullers.

MB: Well, have you got another two hours on the phone? We could be here all night. Basically there’s not another writer who cuts that deep for me. She speaks directly to the experience I had growing up in a small town in the South. That sense of alienation. It’s so fucking heartbreaking. And her style too. People compare everything to Faulkner because he’s the Nobel winner and rightly so. But there’s Faulkner’s maximalism and then there’s McCullers’s minimalism. Carson could take a book like Absalom, Absalom! or The Sound and the Fury and reduce it a novella of 100–120 pages. That minimalism is what I like.

ABP: When did you find her?

MB: Not that long ago. I don’t know why and that’s the frustrating part of it, that it wasn’t introduced to me in school. I knew Harper Lee and Faulkner, and then Padgett Powell, Barry Hannah, and a slew of others like Mary Miller—who I’m in absolute awe of—but Carson somehow fell through the cracks.

ABP: Nobody was talking about her in graduate school?

MB: Maybe they were, but it was always just a name. I remember The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter being an amazing title. But it was one of those “I’ll put it on the list, I’m sure it’s good” books. I thought of her as like Eudora Welty, or just another Georgia writer, someone I’ll get to at some point. Then I read The Member of the Wedding and immediately read all the others. I was like “What the fuck?” I was mad no one told me to read her before then. I was talking to a friend about this recently, about how in all my books there is a love triangle involving a best friend and I always connect that back to Carson. Like in The Member of the Wedding, the “we of me”—I’ll chase that idea in everything I write.

ABP: Well damn, Michael Bible, I sure wish we were hanging out in real life. If we were hanging together right now, where would we be?

MB: We would get a case of Georgian wine and we’d go down to my friend Jane Rule Burdine’s house in Taylor, Mississippi. We’d be on her back porch because I don’t believe in heaven but if I were to envision one, it would be her backyard. We’d bring all the homies down there and get real weird and wild and start howling at the moon. I think we’d all have a really good time.

ABP: That sounds like a ball. And one day, it will happen. Thank you so much, Michael Bible!

MB: So good talking to you, Ashleigh. And don’t forget to send me the name of that Georgian (from the country) writer.

(I emailed Michael after we hung up. Her name is Ana Kordzaia-Samadashvili.)

Ashleigh Bryant Phillips is from rural Woodland, North Carolina. Her debut collection, Sleepovers, won the C. Michael Curtis Short Story Book Prize. Stories from it have appeared in The Paris Review, the Oxford American, and others.

More Interviews