Interviews

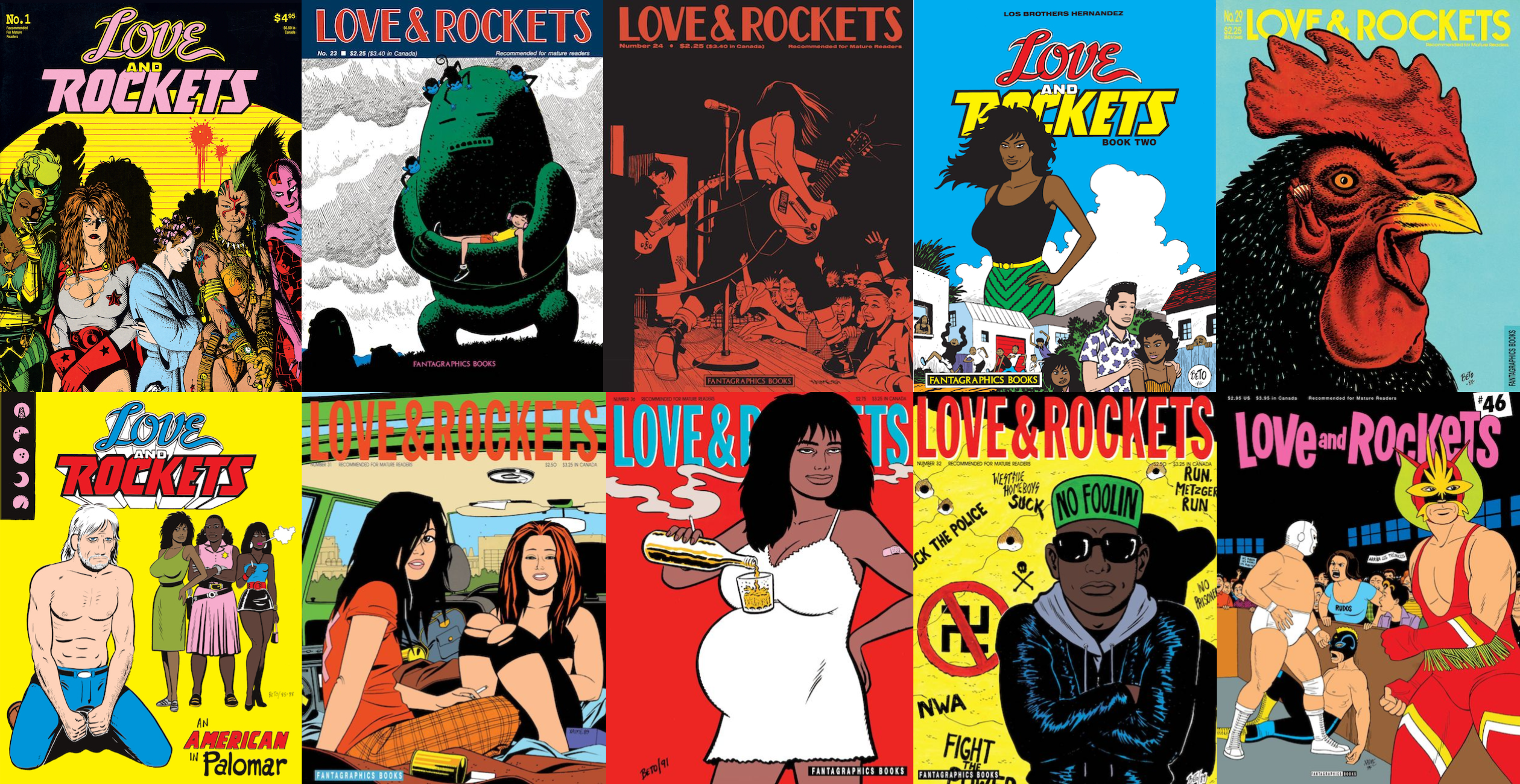

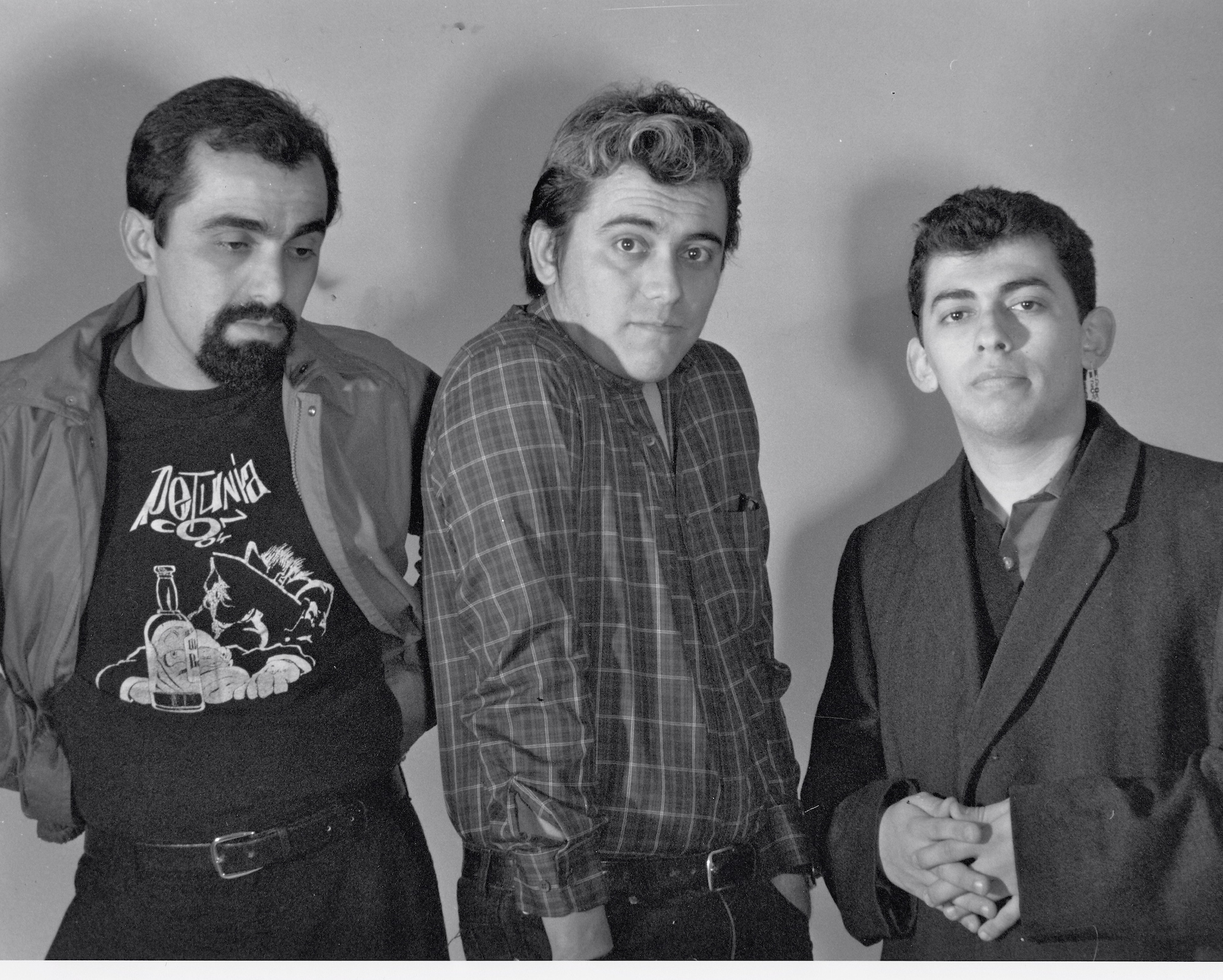

In 1981, three brothers of the Hernandez family (Mario, Gilbert, and Jaime), all in their twenties, self-published the first issue of a black-and-white comic book, titled Love and Rockets. The series, quickly picked up by the fledgling publisher Fantagraphics Books, became a foundational work of the alternative comics revolution of the 1980s, which transformed American and global cartooning by introducing a new narrative and thematic maturity to an art form that had traditionally been ephemeral and geared toward children.

The Hernandez brothers, or Los Bros Hernandez as they are popularly known, are the sons of Santos and Aurora Hernandez, who had six children in all (five boys, one girl). Mario was born in 1953, Gilbert (known as Beto) in 1957, and Jaime in 1959. Santos Hernandez was a working-class Mexican immigrant, working variously as a painter, a traffic cop, and a farm laborer. Aurora’s roots were in the borderland of Texas and Mexico. Both parents had an artistic streak. Santos was an amateur painter, Aurora an enthusiast for comic books who had fond memories of the comic books she read as a youth, which she often imitated.

Unlike many parents of the 1950s, Santos and Aurora indulged their children’s love of comic books, then seen as a disreputable medium. The Hernandez house was awash in comics: the Uncle Scrooge comics of Carl Barks, the Archie comics of Dan DeCarlo and Harry Lucey, the Little Archie comics of Bob Bolling, the Marvel superhero comics of Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko. Later, there were the underground comics of Robert Crumb and S. Clay Wilson, along with the French science fiction stories of Moebius (available in the magazine Heavy Metal). All the Hernandez kids drew homemade comic books, and even in their earliest work they showed an astonishing mastery over visual storytelling, internalizing and synthesizing the styles of the major artists in the field.

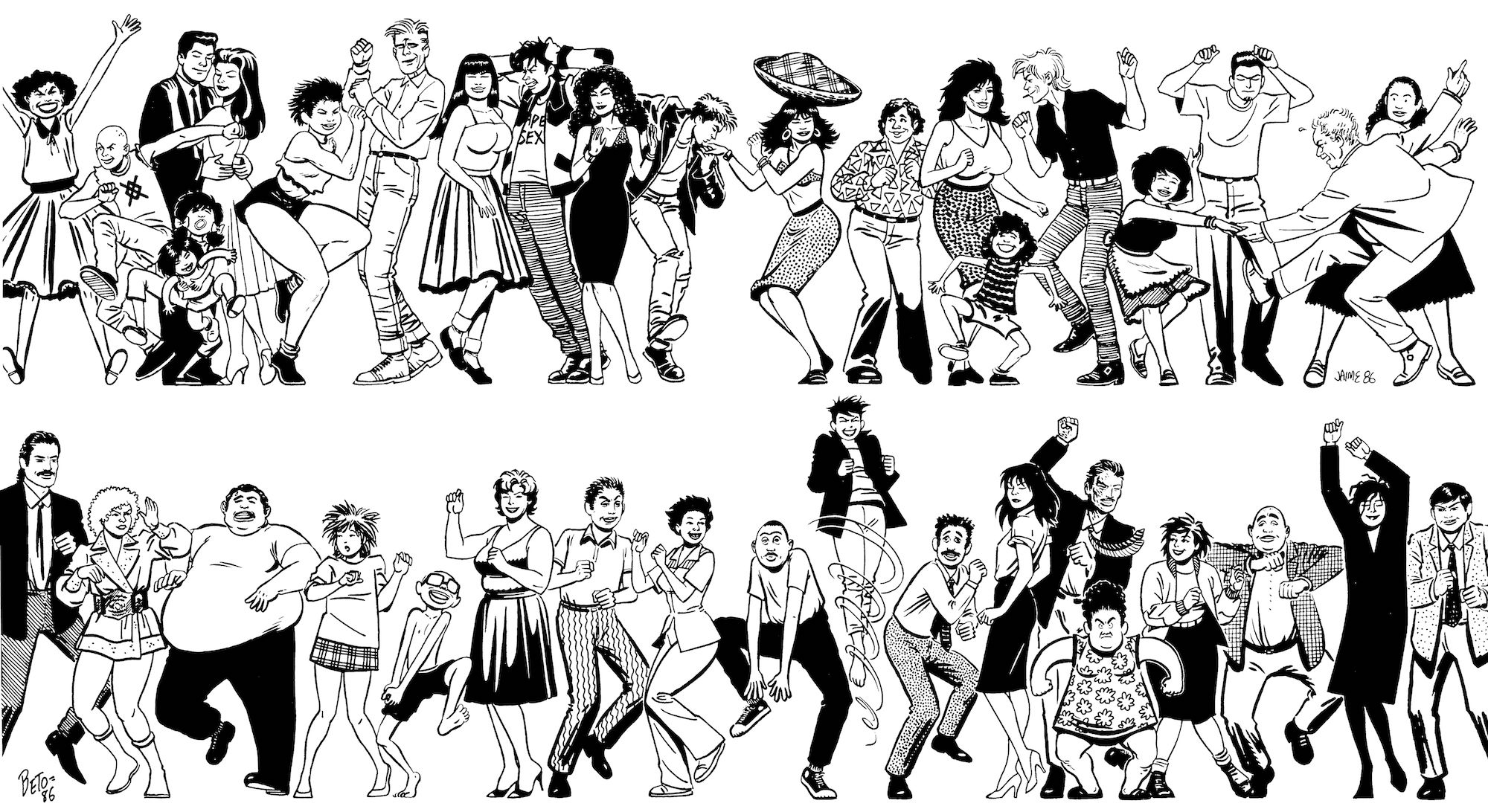

From the start, Love and Rockets was a showcase for Los Bros Hernandez to create comics that presented their personal concerns in the idiom of comics. Mario, the least prolific of the brothers, crafted stories mixing goofy science fiction tropes with political satire. In the first issue, Jaime introduced Maggie Chascarillo and Hopey Glass, the stars of what would become a decades-spanning roman-fleuve now known as the Locas cycle. Latina punks and sometimes lovers, moving through stories that shifted effortlessly from realism to science fiction, and interacting with a multiracial cast that eventually totaled hundreds of distinct characters, Maggie and Hopey were the driving force behind one of the most ambitious narratives ever produced by an American storyteller. Gilbert’s first Love and Rockets story was a witty superhero satire, “BEM,” a romp through the storytelling cliches of Marvel Comics. But by the third issue (fall 1983), Gilbert launched into his own massive graphic novel, now known as the Palomar cycle. Initially centered around the fictional Latin American town of Palomar and starring the hammer-wielding matriarch Luba, the Palomar cycle was as ambitious as the Locas cycle: spanning many hundreds of pages and countless characters, with plot tendrils that extend for more than a century and range from Palomar to Southern California, it is a saga of enormous complexity and emotional depth. Both the Locas cycle and the Palomar cycle are life works that continue to expand page by page and story by story to this day. Love and Rockets is still being published by Fantagraphics, which keeps the graphic novels of the Hernandez brothers in print in multiple editions. To mark the fortieth anniversary of the first Fantagraphic issue, the publisher has just released an eight-volume reprint of the first fifty issues (which includes many articles and interviews with the cartoonists).

Given the anniversary, we thought it would be a good time to sit down and talk to Los Bros Hernandez about how it all started.

Jeet Heer: I want to go back to the beginning, before you guys were even born. Because, in Todd Hignite’s book on Jaime, there’s this amazing photograph of your parents, from 1952, in Mexico. They’re holding Mario. They’re both looking very stylish and jaunty. Even your dad is walking a bit like some of Jaime’s characters, with the pants up. So if you don’t mind, I want to ask about your parents. We could start with your mom. Because your standard comic book story, like Robert Crumb at the back of Zap Comix, has the big fat mom tearing open the comics, saying, “Don’t read these filthy books!” And there are so many cartoonists who have that story, but your mom was different.

Gilbert Hernandez: This is literally how it began. She was taking a message to an office, maybe a doctor’s office. She said she was sitting on a window seat and there were a bunch of comic books laying there, and she picked up a Captain Marvel book, opened it while she was waiting, and saw a three panel progression, very Kurtzman-like, where Captain Marvel is very tiny, then he’s closer, then he’s closer. Which is a comic I’ve never seen, that doesn’t sound like Captain Marvel to me, but anyway. She said she was instantly intrigued. So she kept picking things up. She went to the local market, and comics were a dime then, so it wasn’t like you were poverty stricken if you bought a comic. And that was how she started collecting. She liked the style, the art of it, and the stories. But she did gravitate toward Captain Marvel, the Spirit, Plastic Man, all the better comics, she really liked those. And that was the beginning.

Jaime Hernandez: And this was when she was little? I never heard this story.

Gilbert Hernandez: Oh yeah, she told me. She was twelve or thirteen, around there. Because her drawings were at fourteen. I imagine this was right before.

Jeet Heer: I remember reading somewhere she would draw Doll Man, as well as Captain Marvel. So it sounds like she was really in the weeds, in terms of knowing her stuff. Is it true her mom tore up her comics?

Gilbert Hernandez: Oh yeah. Our mom had to hide hers under her mattress like a Playboy! Her mom didn’t like it. She thought it was crowding the house. She had no judgment toward comic books themselves, just junk in the house. But Mom would swap ’em, do the whole thing.

Jaime Hernandez: Yeah, she’d go to a trading post, regularly.

Gilbert Hernandez: She stopped reading them when she got older and started dating my dad.

Jeet Heer: But she has this history of being a comic nerd. So interesting to have a mom like that. Crumb and others have these stories of their parents telling them not to read comics, whereas your mom was encouraging.

Mario Hernandez: Mom was real supportive with comics. And we got away with a lot of stuff with entertainment. She did her damnedest to keep us all alive after my father died. But they were both inspirational. My dad told my mom, “Hey, give him some of those funny books. These little savages are making too much noise. Get some of those funny books that you used to like.”

Gilbert Hernandez: Mostly, it was to keep us quiet, to calm us down. There were five boys. We’re yelling and wrestling and fighting and going in and out of the house. And Dad just says, “Come on, give ’em some paper and stuff to draw with, and they’ll keep quiet more or less.” It probably was only for a half hour or something, but it felt like all day.

Mario Hernandez: We read these comics over and over at dinnertime. My mom was like, “Get you some comics and shut up and go eat dinner.” And so we’d have a stack, we’d get in line. I’d get a stack of my comics that I wanted to read. Then these guys would come in behind me, and we’d all be there with a stack of comics, chowing down on tortillas.

Jeet Heer: So there are five boys and then a sister. And you guys had cousins next door. How many cousins were there?

Jaime Hernandez: Six cousins next door and then we had cousins in different parts of our town too. Nobody had less than three or four kids.

Gilbert Hernandez: And that was on Mom’s side. On Dad’s side, it was like a billion relatives, we don’t even know!

Jeet Heer: I think that’s a very specific sort of Latino-Hispanic experience. Or immigrant experience. I also grew up with next-door cousins and we had family within a couple of blocks, and my oldest daughter is always saying, “How much family do you have?!” ’Cause there’s always some new uncle or cousin coming out of the woodwork. Whereas I think that, not to generalize, but White people don’t have that experience to the same degree. I feel like that’s left a mark on you guys. You both have these hugely populated universes filled with many characters who all have some kind of connection. Do you think that left a mark?

Gilbert Hernandez: I didn’t even notice until Dan Clowes said in an interview, “If you look at the Hernandez brothers, they grew up with so many people around them, there are always crowds of people in their panels. And me, I have to fight to keep ’em out of the panel!” He grew up a loner, so his stories are all about loners. Whereas we balance so many different characters and personalities on one page or panel. But it was normal to us.

Jaime Hernandez: Also, besides family, the neighborhood we grew up in had plenty of houses with six kids. It was common.

Jeet Heer: Lynda Barry is sort of like that. In the sense that she had this Filipino family, and people living with their grandmother, with their aunt. She also has a very crowded universe. Back to your mom. You said she started dating, and that’s usually the end of comics fandom for normal people. Like once you discover sex, that’s it. But she seems to have an artistic sensibility. At least if she remembered all that stuff.

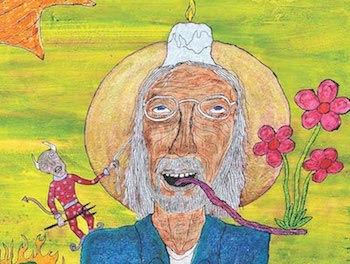

Gilbert Hernandez: She was very drawn to good technique. And like I said, that’s why she gravitated to the better comics in the ’40s. Because she loved how awesome a Spirit page was. And she didn’t know it at the time, but she liked people like Reed Crandall and Lou Fine. She loved that type of art. Jaime can tell you more about it. She would actually copy that style of art. The drawings weren’t exactly panels, but she would take a tiny head and blow it up to an 8.5 × 11, and draw it. And some of those drawings are actually worth looking at. She doesn’t want anybody to see them, but . . .

Jaime Hernandez: I own them! I promised her I would never show them. Even though I’ve shown a couple people. But the thing was, when she showed us, she said, “These are drawings I did of my favorite superheroes.” And we’d ask, “Who is that!?” And she’d say, “That’s the Black Terror. That’s Rusty Ryan. That’s Captain Triumph.” And we were like “Who?” But it was amazing because they look like movie star portraits. Like if you bought eight-by-tens of your favorite movie star, but it kind of worked. In my head I was like, “Wow, this is glamorous!” There’s a lot of shadow and she took from Reed Crandall. I was like, “So this guy is Doll Man? He’s like a doll? What the hell?” But it was so romantic!

Gilbert Hernandez: On the one hand you’d have Doll Man and Skyman, and you think that’s just the old days. Then you’d have Black Terror. There’s nobody more modern with a cool name like that! And once we finally saw the comics, they really had a strong appeal for us. I didn’t care to read them, I wasn’t interested in the stories, but I loved looking at them. The covers, they’re fascinating.

Jeet Heer: When I work out the dates, you guys were born in the ’50s, so it’s odd to me that so much of your work is evocative of that earlier period. But your mom was the bridge. There’s that great cover from Matt Baker, Canteen Kate, that Jaime paid tribute to. I was like, how did Jaime see that cover? Or even become aware of it? Because that wasn’t around. Let’s talk a little bit about your dad as well. He was a painter?

Jaime Hernandez: So we’ve heard. We’ve never seen his work.

Jeet Heer: None of that survived?

Gilbert Hernandez: I don’t think so.

Jaime Hernandez: It’s probably in Mexico. But from what we’re told, he was a painter, a traffic cop. He did a million jobs when he was young in Mexico. And Gilbert, being older, would remember Dad clearer than me. Because he died when I was about to turn eight years old. I still remember Dad clear enough, but the memories are starting to become still pictures now. As time passes.

Gilbert Hernandez: Even before he instigated us drawing together on the floor, he encouraged it. I didn’t know he was a painter or had any kind of artistic interest. Our mom—this is like thirty years ago, after Love and Rockets—she’d once in a while start talking about something from the past that we had never heard before. What? He did what? “Oh yeah, he was very good at watercolors. I told him to save them but he didn’t want to.” So anyway, when we were little, we would lay on the floor, and he would tear up a big paper bag and tell us to draw. And if we didn’t know what to draw he would say, “Okay, draw this, a person’s head. And help the little ones!” He always told me and Mario to help the smaller kids. Not that we helped any, because they could draw on their own, except for our smallest brother, he was too small. But that’s how that started. And once we started drawing, we knew this was a good thing.

Later on, I was really into the Myron Fass reprint books, which were copying the Creepy and Eerie books from Warren, and what they would do is add blood to really shitty black-and-white monster stories. I thought, This is insane! This is crazy! So I would draw hacked-off limbs and things like that, and Dad would say, “Why are you drawing all that blood?” And I’d say, “Oh it’s a monster.” And he would say, “Why don’t you draw something nice, like a lake, or trees?” In my head—I was already a stubborn idiot—I would say, “Why would I draw that? I’m drawing limbs severed! And I get to draw blood squirting!” I wouldn’t say it out loud. But then he would say, “Okay, keep drawing, but think about nice things to draw.” He was saying elevate it! Grow up! But that’s one thing a young rebel doesn’t wanna hear: grow up. You wanna keep doing what you’re doing. Anyway that was the last conversation about art that I remember having with my dad. I pooh-poohed him and he pooh-poohed me and that was fine.

Jaime Hernandez: The interesting thing about that, though, your conversations with Dad were very sparse because his English wasn’t that good . . .

Gilbert Hernandez: Actually by then it was decent. He was a lot better toward the end of his life. He could communicate a little better then. We had regular conversations. He couldn’t remember to say “draw” or “illustrate.” He’d say “write,” which meant draw or paint.

Jeet Heer: So the language around the house. Was it Spanish among the adults and English among the kids? A mixture of Spanish and English? Your grandma was there as well. How were you guys communicating?

Jaime Hernandez: Mostly Spanish, with her. But we were taught mostly English, by the time we got old enough to go to school. Dad wanted us to be English speakers, so we wouldn’t be made fun of. My mom said, “Why not teach ’em both?” And he said no, just English. He got a job where he wanted to speak English and impress the boss. So it was hard to go back to Spanish. From what I understand, we spoke Spanish as little kids, but that went away pretty quickly. I can’t prove this, but I remember being really little, like four, and having a conversation with Dad, and I understood him. But I didn’t know Spanish, or maybe I did and didn’t know the difference.

Jeet Heer: I’ve seen that a fair bit. Some of my cousins would spend time in India when they were little, like three or four, and come back knowing the full language and be able to speak to their grandparents. I think that’s totally plausible. It’s interesting that’s in the 1950s, when in 1954 Eisenhower ordered Operation Wetback, which deported around a million people. Prior to that, people were going back and forth across the border all the time. It was more fluid. Did you guys feel that or sense that at all? That there was more xenophobia, or more “Speak English!” in the air?

Gilbert Hernandez: It only came up when we would go downtown with our dad. He loved to show off his boys. It always worked. He was so proud of us. Some guy would stop him and say, “Those your sons?” And he would say “Yep!” And the guy would say, “Oh you’re a lucky man.” He thought we were going to be ship captains or generals in the army. But no! We were just a bunch of artists! I would only get that sense, though, when he spoke to people. He would say, “Don’t say anything, I’m going to talk to this man.” But his English was broken, so he’d have trouble. And I think Mario helped him out a little bit. But that was the only time we had to act differently in the White world. Which we never thought about with our mom. And then you go to school and start to learn about racism, from other students, other kids. You’re like okay, this guy is an idiot. Because from the very beginning, once I encountered racism, anyone who was a racist toward me or anybody else, well, they were just dumb. Because I knew the kind of people they were making fun of. People who were super nice or friendly or loveable. Jaime, did you feel any of that?

Jaime Hernandez: No, nothing really more than, the older I get, I think back on how White kids would stare at me when I was trying to be their friend. Sometimes they would look at me like, “Why are you talking to me?” Or, “This is weird.” Or maybe I was just obnoxious or something.

Gilbert Hernandez: Or they thought, Oh you’re normal. I think that was part of it too, sometimes.

Jeet Heer: The other element of the family, and I think this will help us get into both comics and also punk rock, is the importance of the older brother. The older brother is always the guy, the one who introduces you to things and shows you the world. In a way that your parents don’t quite do. I guess that’s what Mario was like. You were the pioneer—the guy who knew the work Ditko and Kirby did for Atlas comics, and then later underground comics, and then music.

Mario Hernandez: It was anything comics. If I saw a comic on TV, some kid reading one on a TV show, I wanted to know where I could get it because I was always looking at newsstands. Anything that was drawn—Cracked, Mad, even joke books with illustrations. I ditched summer school to go sit in the library and just look at The New Yorker. I became a historian.

Jaime Hernandez: Let me just say one thing about that. In our house, it was trickle-down. Because Mario would teach Gilbert everything, and then Gilbert would teach the rest of us. Or me. And our middle brother. And so I would get it from Gilbert, which I now understand was a little easier than getting it from Mario.

Jeet Heer: So it was like a hierarchy. So what was the order? Mario, Gilbert, and then Richard?

Jaime/Gilbert Hernandez: Ricardo.

Jeet Heer: Then Jaime. And Ishmael, and then Lucinda. Do you remember how old you were when you started to make your own comics?

Mario Hernandez: We were tiny. My dad would tear open the paper bags and give us crayons, pens, or whatever, and we’d just sit there and scribble on those and then it took off. And I remember my first comic. It was called The Fabulous Two. Really rolls off the tongue! I must have been at least six, maybe seven. And it was done on stenographer paper, the only paper I had. So I just folded that in half and made a little comic.

Gilbert Hernandez: Do you remember who the Fabulous Two were?

Mario Hernandez: Captain America and Daredevil.

Jaime Hernandez: And Radioactive Man.

Gilbert Hernandez: Your own Radioactive Man.

Mario Hernandez: Yeah, that was mine. You got to get your own in there.

Jaime Hernandez: I remember that. It was Radioactive Man and Daredevil. But Captain America shows up in the comic and says, “Take that!”—and he’s socking the wall or something.

Mario Hernandez: And I didn’t write dialogue, so I just wrote these lines in balloons to make it look like dialogue.

Jeet Heer: So you did Radioactive Man before The Simpsons?

Gilbert Hernandez: Before Marvel, actually. In the Emissaries of Evil . . . no, that was Daredevil. Or Avengers?

Mario Hernandez: Number six. Like I said, a historian.

Jaime Hernandez: I wanna go back to the Mario thing, about how it was easier to learn from Gilbert. Because Mario was cut off from us little kids. I was part of the little ones. Mario didn’t want much to do with the toddlers. So he would stick with teaching Gilbert stuff. Sometimes it would just stop there.

Gilbert Hernandez: Originally he was forced to do that. Because our parents would say, “Mario! Show him how to do it!” And he’d be all, Ugh. He’s four years older than me, so I can understand it. He was already a kid who wanted to do his own thing, and here’s this little guy who doesn’t know what to do. I’d set up my little army soldiers and just knock ’em down, that was it. And our parents would say, “Well, show him how to play!” So then I learned to set up scenes. I’d have the army, my little soldiers, the troops on each side. I’ve told this story many times: the first issue of Fantastic Four in 1961. Mario looks at the cover and says, “See, there’s a monster coming out of the ground, and there’s a guy made of fire around it, and there’s a lady, she’s invisible, but she’s trying to get away, and then there’s a guy who makes his body into rubber, and he’s tied up but he’s getting out of the ropes.” Then there’s the Thing, flipping over a car or whatever, and Mario says, “That monster there? He’s the good guy!” KA-BOOM! It completely changed my way of thinking about telling stories. Because it’s not like Frankenstein, where you see him murder people in the movie, and then maybe you feel sorry for him. No, the Thing was always good! And that’s what got me, that he was always good.

Jeet Heer: The genius of those Kirby and Ditko comics is that they took the monster comics, but then made the monsters into sympathetic figures. It’s so interesting that Mario figured that out right from the start. Another interesting thing, and the only comparison is maybe Crumb, is you guys were never just into superheroes. You were picking up Archie, Little Lulu, Uncle Scrooge, Carl Barks’s comics. And, to me, that’s very evident in your work. The way you internalized the basic vocabulary of comics. Can you talk about that? About how thanks to your older brother, all these comics were around the house.

Gilbert Hernandez: After a while it became the medium. We loved superheroes, and the characters, and the comics, and the drawings. The colors. Everything! But the medium was what drew us. Especially Mario. He was even into looking at the ads in comic books and figuring out who drew it. There was a back cover with Roman soldiers that was around forever. It took us a while but we figured out it was Russ Heath. It was like a game, trying to figure out who did the drawings. And sometimes we couldn’t figure it out. Like Neal Adams is easy to spot, because of the style. There was a Schwinn commercial, with a kid smiling, and it’s so Neal Adams. I didn’t know that cartoonists could be ad men as well. But it was the technique and medium that really drew Mario. That’s who we learned it from. And that’s what our mom was into. The drawing, basically.

Jeet Heer: I think that’s a very distinctive thing. A lot of cartoonists talk about Kirby, about Ditko, but as far as I can tell, you guys are the only ones talking about Dan DeCarlo and Harry Lucey. How is it that you were aware that there’s something here that artists can use, and no one else was?

Jaime Hernandez: To me it wasn’t so much a discovery as the fact that I like those comics, and I guess I unconsciously took from what I liked about them. Every year Mom would bring out this bag of comics in the summer and we would read the Archies and Dennis the Menace, and the older I got, I kept going back to the comics that I liked more than others. I didn’t know who Dan DeCarlo was, I didn’t know who Harry Lucey was. But I liked how they did Betty and Veronica annuals, and Archie. And there was a comfortable feeling with these comics. I didn’t look at them from an artistic point of view, like studying them or drawing them. It was more how they made me feel. With [cartoonist Bob] Bolling, and Little Archie, it was like, “Wow, this is full of mood and feeling.” That was the main thing that I got from them. Besides that, they were good storytellers. So I tried to put that in my comics. I want people to feel good when they read my comics, no matter how mean certain characters are.

Gilbert Hernandez: They allowed us to project. Whereas Marvel and DC were already set up with where they were going, what they were doing. Archie comics were so simple and funny and breezy. I felt that I was in Riverdale, with them, hanging out, oddly enough. It has nothing to do with my life, but the way DeCarlo and Lucey, and maybe even the writers—it just gave me a feeling of being there, more than any other comic. Turns out that this was good storytelling from the artists. It goes back to that. There are some Harry Lucey splash pages, and DeCarlo splash pages, they’re the masters of opening a story, up there with [Will] Eisner and Kirby. They’re just damn good artists and storytellers.

Jeet Heer: There’s also a sense that they’re dealing with non-fantastical characters, everyday people. And those Archie cartoons, I guess Kirby was a little bit attentive to fashions, but those Archie cartoonists, they really paid attention to what young people were wearing. The other element I want to talk about, and this also speaks to Mario and his role, is music. You guys grew up on the stuff that everyone did in the ’60s, like the Beatles, but punk rock was the thing that scrambled your minds, like in 2001: A Space Odyssey. That seems like the monolith, what you touched and what made you something different. Can you talk about how that music affected you?

Gilbert Hernandez: It started with Mario and I sharing a room. He was a teenager in the late ’60s, so he was listening to underground stations, the FM stations. He would bring home albums and talk about groups. And I was completely bored. To me, it was just a bunch of farmers playing rock. And something like Jimi Hendrix was just too offensive, it was just too noisy, it wasn’t pretty singing. So I didn’t really gravitate to it until I heard Sly and the Family Stone, and I thought, I like this. So I started listening to music. But it wasn’t until he bought a T. Rex record that was so warped we couldn’t listen to the first songs. So we just listened to the middle of the record on both sides. We made fun of it at first, because it was so simplistic, and we were listening to more sophisticated bands like Yes and ELP, groups like that. But we eventually came around to T. Rex and thought, This is kinda cool! Then we sought out the other glam bands—Slade, Mott the Hoople—those bands made an impression on us. We liked that better than the regular rock on the radio. Later, when it came back as punk, it was dirtier, more political, it had more to say. But it wasn’t that strange to us. We thought, Oh, it’s that music again, but it’s all revved up and crazy and loud. We were at the right age. I was twenty-ish, Jaime was in his teens. The freedom of it. The arrogance. That’s what got us going.

Jeet Heer: What about you, Jaime? Because, for you, punk is the music, but it’s also a whole milieu, a whole culture, the people and the attitude. Like Gilbert said, it seems to have made such a powerful impression.

Jaime Hernandez: I had graduated high school before I heard any punk. Or most punk. You know, I’m out of school, I have no idea what to do with my life, but I was ready to do something even if I thought my life was over. And punk came at that time. It was also a time when I was rediscovering old comics and putting my spin on them, but I didn’t know what to do with them. So I was at a pivotal moment between high school and Love and Rockets, and the music was just there. Gilbert saw some bands, and he tells me, “We gotta go to L.A. We gotta go check this out. This is fun.” And when we finally got into it, it was like, “Okay, I don’t want to do anything else.” Then I got into the fashion, the whole style. But the fashion, coming from a working-class background, I would try to find straight-leg pants at K-Mart. But it was the first time I was part of a “thing”—a whole revolution. I wasn’t thinking about the rest of my life, about feeding myself or whatever. I was just like, this is fun as hell! So I started to create characters to fit that world. I didn’t know if I was going to do anything with it. But it was something I preferred to draw, more than anything else. I liked my little punk Archie world. And I don’t mean Archie, like the characters go on dates. This was more like my experience, my real life.

Jeet Heer: It also seems like there was this attitude, which is important to understand for people, in terms of this whole idea of where doing your own comic comes from. The punk attitude is that music doesn’t belong just to professional bands with managers and record companies behind them. You can make your own music, and go on stage and do it yourself. Punk seems like it’s the crucial element that makes you guys take that step in the first issue, as a self-published thing. It gave you this DIY attitude.

Jaime Hernandez: Yeah, by then it was like, okay, let’s do this. What the hell? If we fail, we fail. We don’t have far to fall. But it was like the world was ours to do whatever we wanted.

Gilbert Hernandez: It inspired us to move forward. Because we’d seen fanzines before. There were comic book fanzines and science fiction fanzines. But we mostly read the comic book fanzines. Then fanzines showed up in the punk scene, but we already knew about them from comics. At first, we figured our comic would be a fanzine. We told ourselves, “Oh it’s a fanzine, we’re not professionals.” Covering our asses if people didn’t like it. But luckily, it was seen differently. What was fortunate for Jaime and me was that we had been drawing since we were kids. So by the time we got to Love and Rockets, we could put out the book ready to go. Not a lot of people could do that.

Jeet Heer: There’s that, but there’s another element. I’ve seen a lot of fanzines from the ’70s, and most people’s idea of a fanzine is Wally Wood and witzend. Let’s have barbarians, but you can see their tits, and let’s have spaceships, but you can see their tits! Whereas, even in the very first Love and Rockets, it’s coming out of that fanzine world but it doesn’t seem like the same thing at all. There’s an added element, which is that you aren’t just guys who are reading comic books and science fiction or in that world. There’s something different.

Mario Hernandez: By the time we were starting Love and Rockets, we were already tired of superheroes and science fiction. We just used them as stepping stones to make it a little more popular. So people would look at it, and when they’re sucked in, then you hit them with the real stuff. Like these guys did and then they just took it from there.

Jeet Heer: I want to get to the underground comics. It seems like Mario was on the ground floor in terms of Zap Comix. How did that stuff hit when you first saw it?

Mario Hernandez: Are you kidding? I loved those cartoons from the ’30s so much, the Fleischer cartoons. Then all of a sudden, here it was in a comic book. That style knocked me out. Crumb was funny and original. It was another one of those “Hey, you can do whatever you want” moments.

Gilbert Hernandez: Underground comics had a whole different attitude, a whole different kind of freedom.

Jaime Hernandez: Another part was I could see, maybe punk helped, I don’t know, but I could see that there was always something bigger than us, something bigger than what we had, our little world. That no matter what I did, no matter how I much stuff I tried to put in my work, I knew there was a bigger world that didn’t care. That helped me think about the scope. And make the work better. Like I want to reach those people that don’t care.

Jeet Heer: In the late ’70s, the situation with mainstream comics like DC and Marvel was bleak. So much so that a top artist like Kirby moves to animation. What was your sense of what the underground scene was like in the late ’70s? Was it a vital path forward? Or something that just had happened before?

Gilbert Hernandez: I was aware of it before. As a kid I wasn’t allowed to look at those comics, but Mario would sneak them in. And I thought they were horrible! I thought, This is vile! But I did like the freedom, that grown men could do these stories. Then I realized it’s all humor and satire. When I started getting older, I thought, Okay, this makes sense. Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, Robert Williams, S. Clay Wilson—all these artists were making crazy good comics! And they were popular!

Jeet Heer: A lot of people talk about how they first heard Dylan, and they realized they could sing themselves. Or they first heard punk rock, and it convinced them that they could do music. And you hear that from a lot of cartoonists. The first time you see Crumb you think, I can do that, I can draw what’s on my mind. And that’s a liberating thing. Was that your experience? You see that and think, I can do anything.

Gilbert Hernandez: Well, only because they were doing it. Because I knew nobody could draw like him. He’s Crumb! And nobody could draw like Gilbert Shelton or Robert Williams or even S. Clay Wilson. They were individuals. They were powerhouses. So it was more just the spirit of “Yeah, they’re doing it! See what I’m gonna do too!” I tried to make early underground comics, but I had no feel for them. They were just awful. Just lousy. They were one-pagers. I was trying to be outrageous. And I realized those guys made crazy stories because they had crazy thoughts. I didn’t have those crazy thoughts, I had my own crazy thoughts.

Jeet Heer: The other thing out there at the time is Heavy Metal. What did Moebius represent to you guys?

Gilbert Hernandez: He was a terrific artist. What he did was make science fiction funny again. It wasn’t stiff and boring. He made it a goof. You had a character going through a science fiction world who didn’t take it too seriously. There’s so much humor and fun in those comics. We took his way of doing things and brought it to our way of doing things.

Jeet Heer: That’s an interesting point. When I think about Moebius in Jaime’s early work, especially in that first Maggie and Hopey story, the way things are drawn, I remember seeing a little pattering of dust behind a scooter that looks exactly like Moebius. But you’re saying it was more than drawing licks. It’s a sensibility.

Jaime Hernandez: Well for me, since I was younger than Gilbert, a lot of the undergrounds passed me by. Until I was old enough to buy them myself. I knew Crumb, I knew Wonder Wart-Hog. But Heavy Metal was the one where I was like, “Oh these guys are doing what they want.” Even if a lot of it was just space adventure. By the time I was a teenager, like fifteen or sixteen, I remember thinking, Okay, this is the way I draw, I can draw anything I want, if I put my mind to it, I’ve arrived at who I am as an artist. But then I started to learn pen and ink, because my brothers told me, “You know, they don’t use ballpoint pen in comics.” Now they do, but I remember thinking, Oh shoot! Now I gotta learn how to do this dip pen! And it took me a while. It was like I was drawing with a twig. But I was influenced by different artists because of their ink styles. Before Moebius, I was really into Barry Windsor Smith’s style. So I would try to do my own versions of that. But what you see in Love and Rockets number one is the end of me experimenting with my Moebius phase.

Jeet Heer: But you also did a bit of figure drawing in college. And your teacher was Bernard Deitz.

Jaime Hernandez: Yeah, Deitz. A real asshole.

Jeet Heer: But he taught you something!

Jaime Hernandez: No he did, he brought something out of me I didn’t know I had. So that was helpful. The whole time I was in art class, my whole fucking life I was in art class, I would sit there and say I just wanna draw comics! None of this is gonna help me draw comics! It did, but I didn’t think that at the time. So I waited all that time until I was allowed to. And that’s why Love and Rockets took off like a shot. Now I could do exactly what I want. I don’t have to listen to what my teachers say. I don’t have to listen to what other artists are telling me. And that was the best thing in the world for me.

Jeet Heer: That helps explain a lot of the energy in that work. I was rereading that first story, and it’s crazy how much is already in there. Not just Maggie, and Hopey, and Rand, but there’s a reference to Izzy. And I think there’s even a reference to Speedy. So a punk universe that you’re going to expand into thousands of pages is already there.

Jaime Hernandez: That first issue was my whole life. My first twenty-one, twenty-two years on earth. That’s why that’s all there.

Jeet Heer: With Gilbert, I wanna talk about his evolution. Because you’ve also been an artist who’s done a lot of different things. In the first issue you have “BEM,” but also a lot of stuff that in some ways you return to later. The underground, the fantastical, surrealism. But then, what issue was Heartbreak—’83, ’84?

Gilbert Hernandez: ’83, yeah. There’s a section in “BEM” that’s very Palomar-like, even though it’s pretty surreal. I don’t know. I just was screwing around. I was already a little cynical. I was thinking about what kind of comics I could do. I didn’t want do Spider-Man. I didn’t even want to do underground. I didn’t want to just copy Moebius. So I decided to use my personality and draw science fiction stories in different styles. “BEM” was laying around for six months, and then it was time to put up the comic. It was the closest thing I had finished. That was how it started, but once we did the first Fantagraphics issue and we had more pages to fill, I went to the Palomar part of the story. There’s a festival, kids running in the street, people getting drunk, sexy women, people yelling at each other, and I thought, That’s where I wanna go. Screw the monsters! Even though monsters are so much fun to draw.

Jeet Heer: The thing with “BEM” is that stuff is so formative, in the sense that you come back to it. You do a lot of playing with genre. Obviously that first Heartbreak Soup story is a kind of breakthrough. We’ve talked about your family. You had a lot of uncles and aunts and a grandma. Did you grow up with stories about the old country? How did these family stories feed into your work?

Gilbert Hernandez: Directly, I think. Our mother and her sisters were born storytellers. And they loved telling stories to kids. We would be home from school and sometimes our mom would take a break from the housework, and she would talk about her childhood. And it was so fascinating to me, a different world. To her these were fond memories. To us it was like a movie! There were so many surreal elements, at least in our heads. So we built a story about these folks, her uncles and cousins and aunts. The way she described them, she was very loving toward them. I brought a lot of that to Palomar.

But what Jaime did was free me. He did Maggie and Hopey with a little science fiction, and I was sort of in that same boat. Not quite as accomplished as Jaime, because he was already doing it. But I had thirty-some pages to fill with issue three. So I dropped all the other stuff and did the Palomar story. Which had science fiction elements in it. But then I kept dropping more of it. I wanted it to stand alone as a story without those crutches. The science fiction, a little bit of magic realism, I kept just enough, like a good old movie. I used movies as an editing device. I said to myself, Okay, they wouldn’t have this in a real movie, but they might have this surreal ghost story, that might be in a movie. I was making this stuff up. That’s how my brain is—a hamster in a wheel, you can tell.

Jeet Heer: Well I’m glad! The point you made about how Jaime freed you up. Also maybe pushed you to do more personal work. You’re brothers, you’re working on this comic series together, doing your own stories, for such a long time. From the reader’s point of view, it seems like you’re egging each other on. I think about Picasso and Braque, working together in a studio. They were like two mountain climbers, each pulling the other one up and going higher. Is that true for you guys? Maybe Jaime can talk a little bit about having Gilbert as an inspiration. What that might’ve opened up.

Jaime Hernandez: Besides that Gilbert taught me everything I knew since we were little. I liked that Gilbert was there because I had a partner to say, “Alright, we’re making comics! Cool!” He was someone I could trust. And when Gilbert would take off telling a really good story, I would say, “Oh, shit. I better pick it up!” Not saying, “I’m going to do a better story than him.” More like I had to keep up with the quality that he was doing, and I had to make sure I was gonna still have my place.

Jeet Heer: On that point, you’ve mentioned before that you think Gilbert has a wilder imagination, and it feels like, from the outside, Gilbert will often go to fairly dark places, in terms of dealing with really tough things, like sexual abuse. But you’ve gone in that direction as well. Is there some inspiration to take from Gilbert’s bravery, in what he’s willing to work with?

Jaime Hernandez: Yeah, I would say so. But it’s also in the sense that I better think more about grown-up things. Because I could be pretty lazy. As in I don’t wanna do a whole story about real life. But mainly it’s about keeping up with the level of the work.

Jeet Heer: I want to talk about the church a little bit because one good thing about Catholicism is it gives you an imagination. And in both your works there’s a whole mythology. Not just science fiction or the Marvel mythology, but the mythology of religion. A sense of demons and things like stigmata.

Gilbert Hernandez: The reason there’s so much in our comics is that we grew up Catholic. In church you’re bored with the sermon. So you start looking around at all the religious imagery. What is this, a Sam Raimi movie? It’s crazy but still cool looking as far as images go. Then we’d go to a market and see the same thing. We saw that stuff a lot growing up, especially being Mexican American.

Jaime Hernandez: We believed in the devil more than we believed in God. The devil is going to get you. God’s not going to do anything, but the devil . . . he will do something.

Jeet Heer: That comes across in the comics. The classic story “Flies on the Ceiling,” where you don’t necessarily know what God is, but we know what the devil is. This goes back to something you guys have been saying. This part of your life—your family, your stories, the religious imagery that you saw in church and in even the marketplace—you put it in the comics. On one level that’s common sense. But there are a lot of people in the history of comics who didn’t bring their life into their comics. Or some did, like Kirby, but in an allegorical form where his working-class background is in the Thing. “We’re going to put our world into a comic.” That seems like such a key decision.

Gilbert Hernandez: What it is, we’re so self-absorbed, we simply wanted to do our story instead of Bruce Wayne’s. That’s all. And nothing against Bruce Wayne or Peter Parker, because we love those comics. But we’re just so full of ourselves that we thought the way we perceived things growing up was more interesting. So we absorbed them in our comics. Our brains work better when we’re telling our own stories.

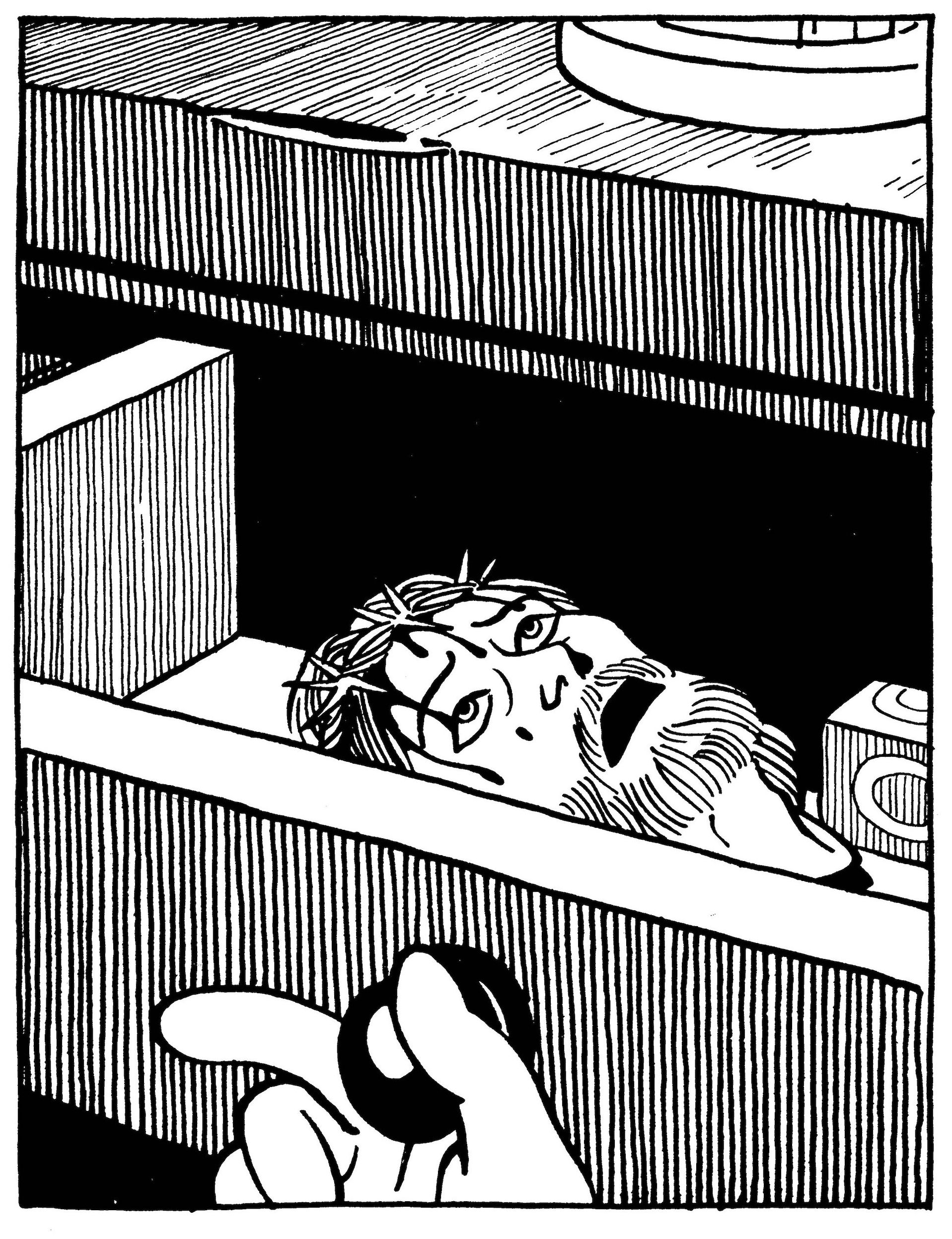

Mario Hernandez: There’s a part in one of Jaime’s stories where Izzy opens a drawer and finds a Jesus head in the drawer. That’s true. In my mom’s drawer. When you go sneaking in Mom and Dad’s drawers, you know? She had a statue in there and I remember not wanting to touch it for years.

Jaime Hernandez: It had this crown of thorns and one time I went to pick it up and it pricked my fingers.

Mario Hernandez: When I saw that in the story, I thought, Geez, he knows how to scare the crap out of people!

Gilbert Hernandez: You know that scene in Carrie? When she’s looking at Jesus and his eyes are lit up? We never made it that far, but I wish we had because it’s scary in the movie. That’s what we grew up with—Jesus, staring at you.

Jaime Hernandez: I remember that scene in the movie. And then later in punk, Exene [Cervenka] from [the band] X. She was obsessed with Catholic imagery. I remember thinking, This is from our childhood. So that kind of helped me get back into that stuff.

Jeet Heer: A question you guys get a lot and I don’t know if there’s a standard or pat answer, but the women characters are very realized. Especially, rereading Jaime’s stuff, it’s very much the case that at least early on, the women characters are much more plausible and fully imagined. And it took a while to introduce a similar complexity for Ray and the other male characters. How were you able to do that when so many others couldn’t?

Gilbert Hernandez: It’s just wiring. Jaime and I are wired similar in that way. In the comic books we read, besides the superhero stuff, the girls were the heroes. Archie Comics and Harvey Comics, Lois Lane comics. Personally, I gravitated to those, and I liked that the women characters acted differently in their own comics. Plus I like drawing women characters. Why would I draw a guy if I could draw a woman? And my job is to make that woman a character as interesting as any guy that I would write. It got so bad that guys were almost eliminated from Love and Rockets. So we had to start bringing them back in. Jaime writing Ray, and I started bringing in male characters because otherwise it was going to be an all-women planet.

Jeet Heer: It’s something in the culture that you guys broke with and I don’t know if there’s any good explanation. I think somebody once said that Jaime is more in touch with the female part of himself than other any man is.

Jaime Hernandez: It doesn’t hurt my manhood to hear that. If I am, then good. I’m one up on the other guys. My ex-wife said that I was just really tuned in to it. If a woman tells me that, then I know I’m doing something right. What’s interesting is that, when Gilbert actually told me to draw women, I was too scared because I hadn’t drawn a woman since I was a little kid. I thought my mom was going to get mad or whatever. But I wanted to draw them. I mean I was a boy, thirteen years old, going, Ooh, look at those curves. The same as any young boy, but it was something that I just couldn’t do because I didn’t know this person. And it was important for me to know the person. So I think that’s where it started, when I was like, “Well, I can’t just do these drawings. They have to be characters.” I didn’t have a take on how men act or how women act. It just turned out that way because it had to be more than just drawing.

Jeet Heer: It’s interesting the way you said it. You draw these characters and then you think, What is their story, what’s their personality? In comics it seems like the writing and drawing go hand in hand. And when you draw a character, there’s so much that’s already implied in it. Even in that first drawing of Luba, which isn’t even a Love and Rockets story, it’s a “BEM” story. There’s something with that character that seems like you investigated it. Is that usually the process? You draw somebody, you start asking questions like, Who is this person that I just drew?

Gilbert Hernandez: Well, for Luba, I was simply drawing the type of science fiction-y, exploitation pinup girl that was in a lot of the European comics. It was normal to have a character like that. But once I started writing her, since she was in the story and she was a villainess, I got to draw her as bitchy as I wanted to. Then I found I could build on that. The end of the story, where she starts a revolution, was a minor throwaway thing. But I thought, That’s more interesting than the thirty pages that I drew because it was fun. So I took Luba and put her in the Palomar story, and it was a small connection from “BEM.” That’s another weird way our brains work. We take something that we did before and then make an entire graphic novel collection with it.

Jeet Heer: That’s also true in the first Heartbreak Soup story. I was rereading it recently and was struck by how many characters you introduced that you later pursued after you finished that story. Did you start thinking, I want know more about this character? What was the process of building the world out?

Gilbert Hernandez: I jump ten years in the next Palomar story. Luba’s dating this guy, and as I said, I like writing Luba because she’s such a contradiction all the time. And the more people were reading, the more people asked, Why does she have to look like a pinup? And I’m like, ”You come from a mainstream where it’s all pinups. So what are you talking about?” There was a weird prejudice toward what we were doing in Love and Rockets because people were feeling, especially through Jaime’s stories, that this story is their story. So when they would see somebody that bothered them, they would say this doesn’t belong in my world. I took that as a challenge. I’m going to keep her and I’m going to make her better and make her the most important character in the whole series. That was a conscious decision. You can’t tell me I can’t draw her like that. You can’t tell me that if a woman down the street looks like Luba, she’s a lesser person. She’s just as much of a person as any of the other characters. And for me, that’s how it works. For each and every character I put on the page—no matter what they look like, the guys with balding heads or paunch bellies, the girls putting on weight, whatever it is—they’re a person first.

Jeet Heer: Want to talk more about the prejudice against Luba as a character? Is it an ethnic thing? Like she’s too much of a Latina woman? Why do you think there’s such a resistance to that?

Gilbert Hernandez: It’s just personal prejudice. Those people wouldn’t like someone like that in real life and they sure as hell don’t want them representing them in their comic. I think it’s that simple. I don’t think a lot of people are aware of it. They just get a bad feeling. And right away it’s “Oh, well, this is bad. This is a cliche. This is a male fantasy.” But after a while people backed off because I de-glamorized her by having her be a mother to a bunch of kids. It wasn’t a big deal. It was my artist’s interpretation of how to do something like that. You tell me not to do something, I’m going to do it more.

Mario Hernandez: Jaime said every time somebody asked when are you going to have Maggie lose weight, he’d put another ten pounds on her.

Jeet Heer: Some artists might feel oppressed by having such passionate fans that are also trying to tell them what to do. Out of my insanity, I occasionally leaf through old issues of The Comics Journal, and I was looking through these interviews from 1980 and ’81, with Gil Kane and Dennis O’Neil, and I was reminded that you guys were doing a lot of spot illustrations for the magazine back then. This is my only claim to fame: I was at least aware of you guys before the first issues of Love and Rockets.

Jaime Hernandez: That was interesting ’cause they really liked Gilbert’s, but they didn’t like mine. And it was because I kept sending them superhero drawings. And they were like why are you sending superhero drawings. I was like, “That’s what your fucking magazine is!”

Gilbert Hernandez: Magneto was on the cover!

Jeet Heer: Jaime did that illustration for The Comics Journal of Robin as a girl. Which had a huge influence. I’m pretty sure Frank Miller is on record saying that inspired him for Dark Knight Returns. So spot illustrations are also a part of the history of comics. They finally figured out how to solve the problem of Batman and Robin being gay. You just make Robin into a girl.

Gilbert Hernandez: Or bring in Aunt Harriet.

Jeet Heer: That’s right, bring in Aunt Harriet. This is a bit of a self-indulgent question for Gilbert, just because of my interest in Gasoline Alley. In a couple interviews you mention Gasoline Alley as an inspiration, and I’ve always wanted to know more about that.

Gilbert Hernandez: Frank King—he was the man. Well, actually, Dick Morris ends the story. Mario would read books on the history of the comic strip, and I was fascinated by it. That’s how I caught on to Gasoline Alley. It was just about this guy and a gas station. The main character [Walt Wallet] finds a little kid, a baby on the doorstep [Skeezix]. He has to take care of this baby over the years, and that’s how the strip changes. That little kid grows up, and as a man, Skeezix says, “I’m a forty-year-old man and I haven’t done anything with my life.” He laments it. My head exploded. Oh my God, I thought, this is awesome. But the thing is it’s not a time jump or a flashback. And that’s important. Nobody ages in a Marvel comic, because they have to be cartoons and toys. Frank King, he earned that, making Skeezix grow to be a man and then Dick Moore taking it over. That was mostly the thing. That it was earned.

Jeet Heer: That’s true for both the Locas cycle and the Palomar cycle. Just the fact that these characters have been around for so long and have aged and gone through these experiences. That’s such a powerful thing and it’s something that you were thinking about fairly early on when you’re doing these stories. “I’m going to be with these characters for a long time.” Was it the same for you, Jaime?

Jaime Hernandez: Yeah, but I was taking it one step at a time. I didn’t have a long-term plan and it wasn’t until I started thinking about Maggie having a family, that she had a mom and dad both still alive. And she’s got a sister. When you start adding family members, the world grows and their world becomes real and so aging is part of growing up, period. The past and the present leading into the future. I started to know them better. I know Maggie’s story before she was born. Like Gilbert said, these people are real, you know?

Jeet Heer: One of the most powerful stories you’ve done is when we find out Maggie has a brother in Browntown. At some point you said that you know what Maggie’s life is like and you can imagine what she’s like at forty or fifty. But you didn’t know what Hopey was going to be like. Then you figured it out. What was the process of figuring out what Hopey was going to be like when she’s fifty?

Jaime Hernandez: When we were punks, we had all these friends. Then we fell out of touch. But twenty years later, out of the blue, they started coming back, appearing in our lives again. I started to understand what happens to punk rockers later in life. They either stay punk or move on. Hopey was one of those characters who I couldn’t imagine living to old age, until I saw it in my friends. That’s basically it. I couldn’t imagine some of the characters growing up. But now I can picture them all growing old.

Jeet Heer: Most of your story is set on the American side of the border. But you did a Mexico story in “Flies on the Ceiling.” Have you ever thought about doing more on that side of the border?

Jaime Hernandez: The only thing I can think of is Izzy goes back to Mexico. I have a plan for a new Hopey/Izzy story. Izzy befriends the little boy that was in “Flies on the Ceiling.” He’s a grown man now and his dad has died. The man that Izzy fell in love with. But that’s it. So far I don’t have an actual story.

Gilbert Hernandez: I’ll help you out, Jaime. That kid’s name is . . . Beto! ![]()

Jeet Heer is a national affairs correspondent for The Nation and host of the weekly Nation podcast The Time of Monsters. The author of In Love with Art: Françoise Mouly’s Adventures in Comics with Art Spiegelman (2013) and Sweet Lechery: Reviews, Essays and Profiles (2014), Heer has written for numerous publications, including The New Yorker, The Paris Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, The New Republic, the Guardian, and the Boston Globe. With Chris Ware and Chris Oliveros, he has coedited the Walt and Skeezix series reprinting Frank King’s Gasoline Alley comic strip. He has also written introductions to many books of comics, including the works of George Herriman, Harold Gray, and Milton Caniff.

With older brother Mario and younger brother Jaime, Gilbert Hernandez cocreated Love and Rockets #1 in 1981. It may have been a very small, black-and-white affair, but forty years later, the series is considered a modern classic and the Hernandez brothers continue to create some of the most startling, original, and intelligent comic art to be seen since the 1960s underground boom. Gilbert lives in Ventura, California, with his wife and daughter.

Together with his brothers Gilbert and Mario, Jaime Hernandez cocreated the ongoing comic book series Love and Rockets in 1981, which Gilbert and Jaime continue to this day. Love and Rockets has since evolved into one of the great bodies of American literary fiction, spanning four decades and hitting countless high-water marks in the medium’s history. In 2017, Jaime (along with Gilbert) was inducted into the Will Eisner Comic Industry Hall of Fame. He lives in East Hollywood, California, with his girlfriend and two cats.

With younger brothers Gilbert and Jaime, Mario Hernandez cocreated and self-published the first Love and Rockets zine in 1981. The Hernandez brothers’ anthology title became Fantagraphics’ flagship comic in 1982 when the independent began publishing it, and Love and Rockets has since become a long-running, internationally acclaimed comic book series. Mario drew and wrote the occasional story for Love and Rockets, such as “Somewhere in California,” and still contributes writing, story ideas, and dialogue. In 1993, his one-shot solo comic, Brain Capers, was published, and he worked on projects such as Mr. X, Citizen Rex, and the anthology Real Girl. He won an Inkpot Award in 2012 and lives in Portland, Oregon, with his wife and children.

All art by Love and Rockets

Photo: Carol Kovinick Hernandez

Show Me Your Shelves | Theo C. Van Alst

In October 2021, Diane Williams published her tenth book of fiction, How High?—That High (Soho Press). In 2000, she founded the independent, not-for-profit literary annual NOON, which she continues to edit and publish each year with the help of a small team of dedicated editorial assistants. Her personal literary archive, as well as the archive of NOON, was acquired in 2014 by the Lilly Library.

NOON is one of the last print journals to accept only submissions sent by mail. The address of a Manhattan postbox—care of Diane Williams—is provided on the journal’s website, along with instructions to include a stamped, self-addressed envelope for reply. No cover letters or previous publishing credits are necessary for consideration, and Williams reads every submission that comes in. NOON is also one of the few print journals that fully earns its physical existence—it’s a carefully designed, handsomely produced object, with full-color reproductions of visual art alongside its elegant pages of text.

Like her books that came before it, How High?—That High is challenging, surprising, unsettling, and very funny. I’m convinced that Williams—as a writer and as an editor—has access to some hidden, ancient source of energy and inspiration. Reading her work, and the work she publishes in NOON, unfailingly encourages me to write my own: it’s like a little lever has been cranked in my head. She gives attentive readers the sense that anything in life can be written about in a dynamic, heroic way. The horizon expands with limitless possibility—the most sublime gift.

Williams and I spoke by email in September 2021.

Kathryn Scanlan: When did you start writing?

Diane Williams: I could say that the inaugural year was 1965, when I studied with Philip Roth at the University of Pennsylvania. I had a story in The Pennsylvania Review that I was proud of, “The Goddess,” in 1967.

KS: In an interview with John O’Brien, you mention studying “English literature, and sculpture, and drawing, and many ‘ologies’” at the University of Pennsylvania. Did you have the idea at the time that writing stories was something you wanted to do, or was it a surprise to discover your interest in it? Had you read Roth’s work prior to signing up for his course?

DW: I thought of myself as a dancer during those years. I also loved life drawing and creating likenesses of family and friends. I do not remember measuring my interest in writing. And it may be difficult for you believe just how empty of ambition I was back then.

Prior to studying with Roth, I had likely read Goodbye, Columbus, and then following the course, was keen to read all of his books during the sixties and seventies.

KS: Do you still think of yourself as a dancer? Because I remember that from other interviews—that you were a gifted modern dancer who began practicing at the age of eight—and it’s pleasing to me to think of you as a writer who dances but also as a dancer who writes stories. Your work has the poise, discipline, physical grace, and sudden, disruptive turns I associate with demanding, rigorous dance—something like the Martha Graham technique, which has been described as “powerful, dynamic, jagged, and filled with tension.” To me, the compact, expressive, irreducible quality of any story by you suggests a completed movement, a piece of performance art.

DW: You can’t know how much I appreciate your finding the presence of vigorous dance in my writing—and I wish I could think of myself as a dancer. I love to feel ready to dance, and certain music makes movement impossible to resist and certain stories do too.

Here’s the chance to offer a wonderful quote from Martin Buber on the subject (from Tales of the Hasidim):

A rabbi, whose grandfather had been a disciple of the Baal Shem, was asked to tell a story. “A story,” he said, “must be told in such a way that it constitutes help in itself.” And he told: “My grandfather was lame. Once they asked him to tell a story about his teacher. And he related how the holy Baal Shem used to hop and dance while he prayed. My grandfather rose as he spoke, and he was so swept away by his story that he himself began to hop and dance to show how the master had done. From that hour on he was cured of his lameness. That’s the way to tell a story!”

KS: I love this and I think it speaks to the sort of madcap struggle toward vitality, deep feeling, engagement, and stimulation that I find in your storytelling. Thinking about your characters, I picture a heavy sleeper, roughly roused, running headlong into her day on earth, pursuing pleasure, love, and meaning in a manner sometimes manic, frantic, even desperate, and often without a clear view of her object—but there’s the sense, as with the rabbi’s grandfather, that animated, agitated, emphatic speech can cure her (our) condition. Do you consider the act of writing to be curative? What about the act of reading or listening to stories?

DW: Well, I hope that some of what you say could be true, and I identify with that provoked character on the loose that you describe, except that I don’t ever sleep deeply.

I do think that the act of writing is curative. It is for me when I can yank the wrath or pain out of myself and put it over there, after having stabbed or stirred it to suit my purposes and whims. Reading and listening to stories—the great ones—is soul-preserving.

KS: Do you think you understood that early on, and that’s why you returned to writing later? I ask because given your talent and interest in other artistic mediums, I wonder what it was about writing stories that brought you back to it—and with so much ambition?

DW: No, I never understood art’s curative powers early on. I knew that I could write while at home taking care of my children. So my choice was merely practical. And it was clear to me I needed another difficult challenge beyond childcare—but the outsized ambition that soon over-whelmed me? Where did that come from?

I have a rehearsed answer that I have given, but I am still moved to ask myself this same question, while waiting for more clarity, as the demands and the character of each era of my life change—and especially these days when I feel especially whipped or emptied.

KS: For whatever it’s worth, from my perspective it seems like you’ve always been ambitious, even as a young person when you say you were “empty of ambition,” . . . I imagine it being thwarted or suppressed instead. I think about your dance teacher encouraging you to pursue your practice professionally, and your parents forbidding it, for example.

DW: Well, I was aware of feeling pride and I was quite startled by my parents’ dramatic and negative response. Was I ten or twelve? My dance instructor at Penn, Malvena Taiz, also pressed me to become a professional dancer, and my writing teacher, Jerre Mangione, encouraged me to pursue graduate work with John Barth at Johns Hopkins. Apparently cowardice intervened—or my indoctrination—that I should study instead to remain a shadow figure in my own life.

But I realize that I do not have a well-clarified concept of my own ambition. I tend to think of ambition as thrashing effort fueled by thoughts at the forefront of my mind, of the kind I experienced during the eighties, when I harried myself with slogans to keep on at the impossible task. On the other hand, if ambition can be described as the quiet acceptance of an obligation to work doggedly at difficult work, even the work of being dutiful—then, yes, I have always been ambitious.

KS: Even when you started at Doubleday after college, you’ve talked about how there were separate tracks for men and women who wanted to be editors: men were given editorial assistant positions but women had to be secretaries first. To resist the indoctrination when you did—later, after you had a family—seems to me even more impressive and heroic. You say “cowardice,” but in my view your path as an artist is the exact opposite! And it seems like this struggle contributed to the urgency and intensity of your work—its bottled-up energy and the sense the author is writing to save her life.

DW: Your description is very generous, but I remember viewing competition with other avid people as an ugly option and it made me feel afraid.

But later on, in mid-life, the bottled-up energy—rage?—was undeniable, and yes, I did feel as if I was writing to save my life.

KS: This makes a lot of sense to me—there can be that grim aspect of competition and it seems reasonable to want to avoid it. Do you think of ambition and competition as necessarily related or joined?

DW: They are certainly related, but not necessarily joined. NOON is the product of the pleasure I take in featuring my colleagues’ strong work, and I am always touched by how the other NOON editors, all of whom are ambitious writers, rejoice when we hear of a contributor’s success and notice. Yours!—for instance.

KS: I think one of the achievements of NOON—in addition to its crucial support of work that might not otherwise have a platform—is the sense of community it builds among its contributors and editors. I’m always hoping and cheering for the achievements of NOON fellows. I’ll ask it tongue-in-cheek because I doubt it has an answer, but how did you cultivate this? From my view, it has a lot to do with your strong editorial presence.

DW: I doubt there is a clear answer. You may be right about what you surmise—I just don’t know. I will also add that our NOON staff is a remarkable team of brainy and exceptionally bighearted people.

KS: I keep thinking about something you said in a recent podcast for the London Review of Books: “I think of myself often as she. What does she think? What will she do? And I pay tribute to her, or I find fault, and I see that I have these exorbitant goals and I’m very surprised, more often bewildered, because it’s very hard to do what she wants me to do.” This feels like an accurate description of the ambivalence and exhaustion of ambition, and it makes me think of something you’ve said about dance that also feels applicable to writing: “I loved choreographing and improvising, and pushing myself beyond what I thought I could physically endure.” Are there things you do to sustain or replenish yourself in order to continue your difficult work?

DW: There is the employment of habit. I am a writer—I write. I wake early these days, 4:00 a.m., and I write six days a week.

Oh, I know what I do. I goad myself—I will buy a prize for you if you finish this book.

Long ago, I told myself I didn’t care what the goad was—tawdry and base, too shaming to share here, or dignified and lofty.

KS: I wondered if looking at art might be something you do in this way, as reprieve or refreshment?

DW: Great art enlarges the spirit, I know that. Another refreshment I can count on is a day spent without specific intent.

KS: “A day spent without specific intent”—that makes me think of the sewing you’ve taken up in recent years and talked about elsewhere. From an interview with Annie DeWitt: “I bought colorful spools of thread . . . and I just started to sew every which way. I know nothing about doing this in the prescribed manner . . . I tell myself that it is not possible to make a mistake. This is perfect:— no plan, just stitch forward, playtime.”

DW: Yes, that still is exactly my view of my needlework—where in the evenings I can take refuge.

KS: Yet your writing—while being deliberately, meticulously worked—also has this feeling in it: playful, abrupt, unplanned, very free. It’s a lot of fun to read and I get the sense you have fun composing it. Do you ever make yourself laugh out loud while writing?

DW: I am very glad you find my fiction fun to read! It is a high compliment. And yes, I may laugh while composing—but this is not necessarily a sign of triumph. The next day I am often baffled by the very same passage and it needs to be stricken.

My novella, though, On Sexual Strength, when I reread it, can get me laughing. I find absolutely everything that Enrique Woytus does or says hilarious.

KS: I do too! The form of that novella—broken into short, titled sections or chapters like “Both Were Busy with Their Penises,” “I Knew I Liked Sex,” and “I Was Actually Horribly Weakened,” for example—is perennially exciting to me and I think it amplifies the hilarity. You first used this strategy ten years earlier, in The Stupefaction. How did you arrive at this approach? Was it a way to maintain the energy of your stories in a longer work?

DW: I arrived at this approach because it was the only tactic I could think of to sustain the project . . . I would have to fool myself into believing that I was writing stories. I discovered—and it was a delightful surprise—that the chapter titles in The Stupefaction create, when read on their own, a sort of parallel narrative or chorus.

KS: Would you be able to talk about your first collection, This Is About the Body, the Mind, the Soul, the World, Time, and Fate? I’m interested in how it came to be published, how long you worked on it, how you felt about its publication . . .

DW: This Is About . . . took three years to write, and a big bunch of these stories appeared in Gordon Lish’s Quarterly, but nonetheless he did not opt to sign up the book at Knopf.

He said my fiction was just too eccentric and he did not want to jeopardize the many other books he planned to put forward. (In later years, he claimed to never have said this, so his decision remains mysterious.)

He also predicted that I would “crumple up” with all the rejection I’d be sure to receive. I have not ever forgotten his exact words crumple up.

Kim Witherspoon, who was just beginning her career, agreed to be my agent—said she loved the stories—and then wrote to say she needed to withdraw her offer because she feared she’d be unable to sell the book. So I pleaded with her to reconsider. She agreed on the condition that I would not blame her if we were unsuccessful.

This was an easy bargain to make and we quickly sold the book to Mark Polizzotti at Grove Weidenfeld!—which was the outcome I had prayed for.

Everything about that publishing experience was stellar, was thrilling, and the book received a wide and positive critical response. But unfortunately Grove then underwent considerable upheaval, as it acquired new owners, and its staff was all changed out.

I was assigned a new editor, and the company was still eager to publish my second book, but Grove was sold yet again and there was more chaos.

And even though my second book—Some Sexual Success Stories, Plus Others in Which God Might Choose to Appear—fared even better than the first, the new editors were not interested in my next book, The Stupefaction, which Gordon Lish was then delighted to take on at Knopf. But before this book launched, Lish was fired.

So there was no open road forward. The Knopf staff that took on The Stupefaction made it clear to me that they would do absolutely nothing to support the book or to promote it.

KS: Terrible! But not that surprising. Do you think the book suffered as a result, in terms of its visibility and reception? Do you have a sense of why Lish was keen to publish your third book after passing on your debut? How did you come to be published by Dalkey Archive after that (Excitability: Selected Stories and Romancer Erector)?

DW: Somebody commented then, I can’t remember who, during that period, that Knopf liked to create Fabergé eggs and then crash them. As for Gordon Lish’s change of mind—he is and was notoriously mercurial. I didn’t wonder too much about his turnabout. Also, he had been consistently—throughout those years—supportive of my fiction, and he continued to publish it with frequency in The Quarterly.

I was a great admirer of Jack O’Brien—his mission and his courageous independence—and he had a high regard for my fiction. I was very lucky that Dalkey Archive Press was in the world and that Jack came to my rescue.

KS: When you were writing your first collection, did the fact that you were raising small children give you a sense of renewed or increased appreciation (or reevaluation) of language—witnessing their learning of it, teaching them how to speak and write?

DW: I have never thought of this before! What an interesting question. Raising children certainly brought extra drama, dilemma, joy, boredom, and continuous interruption.

I taught myself to work under all and any conditions. I do think my language was more naturally lyrical in those days, though I cannot be confident why.

KS: I often think about what a rare privilege it is to be able to send work to an editor who also happens to be an important, groundbreaking contemporary writer—and she will read it! Do you feel like the work of editing and producing NOON—every year for the past twenty-one years!—is a way to take a break from yourself, from your own writing, or does it feel closer than that, like a relation to or extension of your fiction? Does working on NOON influence what you write?

DW: Well before inaugurating NOON, you know, I edited StoryQuarterly for twelve years, so this vocation has become second nature.

I use the same timeworn, straw African carryall—which holds the necessary accoutrements for the job—that I have been using for thirty-plus years. It’s where I keep the blue folder for the rejection slips, the pouch that secures the Scotch tape, and the miniature silver knife—a letter opener—that was gifted to me by Gordon Lish, as he said offhandedly, “Here! You need it more than I do.”

As I weekly take up the stacks of submissions, this ritual brings to mind other earlier times when I read stories alongside Anne Brashler for StoryQuarterly—we had fun. And NOON has been so lucky to have had succeeding teams of brilliant and dedicated editors.

But evaluating submissions is a difficult and grave responsibility, and as an author who has submitted my own fiction for years and years, and who undergoes profound apprehension while waiting for the verdicts, I feel keenly the obligation to read these submissions right away and to respond right away.

Does editing influence what I write? Likely it does. I am inspired by the fiction we publish.

KS: There’s a feeling of coherence or unity in every issue of NOON that’s a testament to your vision and your sensibilities as an editor. There might be a conception among some that everything in the journal is heavily edited by you, but I know that you also publish work that has received very little in the way of edits. How do you view your role as an editor?

DW: Editing NOON offers me the opportunity to be in conversation—sometimes extraordinary communion—with other writers whom I admire. I consider this a great gift and a privilege, and if we can deepen effects, enhance the power of a piece, we aim to do this.

KS: Laura Sims wrote this about your work: “Can we allow ourselves the freedom she offers of beginning at the physical end? Some readers may not be able to accept this and similar challenges inherent in Williams’s work.” And in an interview for The Paris Review, Iris Murdoch says, “You have the extraordinary experience when you begin a novel that you are now in a state of unlimited freedom, and this is alarming.” If freedom is the ideal of art, why do you think it can be so challenging and frightening?

DW: Freedom feels like a fine thing if one also feels safe, but what about vertigo, which is certainly related? I loved to feel dizzy when I was a girl. Did you ever spin around in order to fall down dizzy?

As an adult, of course, for me, dizziness foretells physical or mental trouble, the exception being those stunning and positive psychological reformations that I have experienced, that have initially caused loss of balance. This sort of untethering—if it occurs at the end of a tale, I find it invigorating.

KS: I don’t remember trying to make myself dizzy, but I loved the exhilaration of swinging too high on a swing set or riding a horse too fast, or a bicycle, which gave me the thrill of possibility and danger I think you’re talking about—the invigoration of untethering. It makes me wonder if fiction is a way to actively pursue disorientation.

DW: Yes, I can agree with that!