Scribes for the Darkness | An Interview with Mariana Enriquez and Megan McDowell

Interviews

By Sarah Booker

My first encounter with the Argentine writer Mariana Enriquez’s work was in a bookstore in Barcelona in 2017. I was there with the agent Sandra Pareja who pressed Las cosas que perdimos en el fuego (Things We Lost in the Fire in Megan McDowell’s translation) into my hands, assuring me that she was the real deal. Wow, was she right! I devoured that unsettling story collection inhabited with a one-armed girl who gets lost in a house, women who set themselves on fire, and abandoned children sleeping on a dirty mattress on the street. Mariana’s writing grabs onto her reader and does not let go, insisting that these characters and settings linger long after we close the book. As soon as I got my hands on Nuestra parte de noche, which came out at the very end of 2019, I dove into this world of body parts, cults, the occult, and friendship. I was still reading it as the pandemic set in, causing an even more intense emotional attachment to the novel and its characters.

Nuestra parte de noche is a novel about inheritance, darkness, and transcending the body. It opens as a young Gaspar and his father, Juan, travel to northern Argentina. There, Juan will participate in a ritual at the center of a cult called the Order, of which his late wife’s family are high-ranking members. We soon learn that Juan is a medium for the Darkness and is able to conjure it in these rituals. The Order is convinced that Juan’s son, Gaspar, will have this same ability and is desperate to use him. Moving through time and space—from the Argentine dictatorship of the 1970s and early 80s, 1960s swinging London, and the return to democracy in Argentina in the 1980s and 90s—the novel traces the Order’s attempts to control their mediums and the work these mediums do to win their freedom.

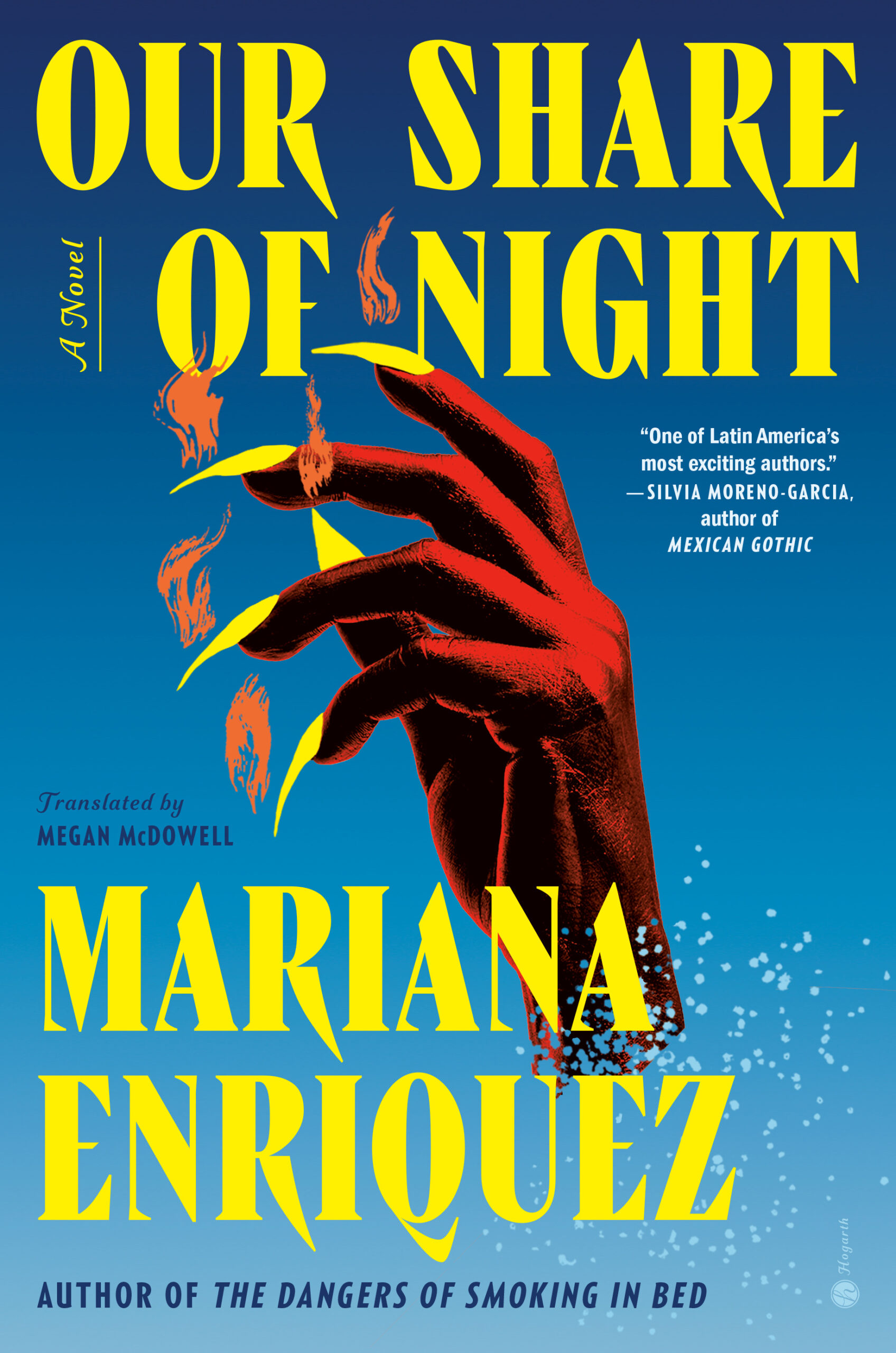

The English-speaking world is now in for a treat as Megan McDowell’s beautiful translation of Nuestra parte de noche—Our Share of Night—is finally available (published with Granta in the UK and Hogarth in the US). Born in Kentucky and currently based in Santiago, Chile, Megan works with some of the most exciting Latin American writers, including Mariana Enriquez, Samanta Schweblin, and Alejandro Zambra. Returning to this book was like returning to a horrifying yet totally engrossing dream, and Megan’s English does a marvelous job bringing these characters and dense settings to life. I’m taking advantage of the US publication of the novel to converse with Mariana and Megan about the book and their collaborative work over the years.

Sarah Booker: Given this novel’s search for origins and legacies, I’d like to start with the book’s inception. Mariana, how did you come to write this book? Is it a project that has been in the works for a long time, or was it a shorter-term project?

Mariana Enriquez: I wanted to write a genre novel for some time but, honestly, I have been writing short fiction and non-fiction for a while and wanted the obsessive and immersive experience of a novel. I started with the (let’s say) supernatural plot because many of my short stories start with an idea. So it was the Order, the God, the Medium, the occult, the folklore. And from there came the story of the characters, and the whole novel became a tale with a lot of levels. I worked on it for two years, but I had been thinking about it for a longer time, years before starting to write.

SB: Megan, this is now your third translation of a book by Mariana. How did you come to work with her? As a translator, how do you understand Mariana’s writing and its unique qualities?

Megan McDowell: I think it happened when Anne Meadows at Granta asked me to write a reader report for Things We Lost in the Fire. I loved it so much that when she bought it, she thought of me for the translation. I just went back and found that report from 2015, and it starts with this line: “Mariana Enriquez is not kind to her readers; she does not coddle or appease them.” I still think that’s pretty true, in the sense that Mariana’s fiction makes us look at things we might rather not look at. I still appreciate her socially aware incarnation of horror and her sensitivity to nuance, two things I also mentioned in that report. But I also think that the heart that beats underneath the horror is a benevolent one, and that Mariana does us, her readers, a great kindness when she gives us these stories. I appreciate not only Mariana’s talent but also the fact that no one else could write what she writes. Maybe that’s how we know a writer has really found their voice. Mariana takes her specific set of influences, interests, obsessions, and concerns and spins them into stories that are very particular yet also implicate us all as readers.

SB: Mariana, could you talk about the character development in this novel? I’ve heard you speak elsewhere about how Juan is modeled on Wuthering Height’s Heathcliff. Why was Heathcliff the right model for Juan? I’d also love to know more about the development of Gaspar. I really connected with his story and felt a lot of sympathy and admiration for him and the choices he has to make. Adela also totally fascinates me. I’m curious why you brought her back from your story “Adela’s House.” What is the significance of this character for you?

ME: I wanted Juan to be uber-attractive and demonic and very sexual, which Heathcliff is for me. Also, Heathcliff is not a villain: he has a point. He is full of resentment. He’s been treated as a servant. The phrase “haunt me” is uttered by Heathcliff to call Cathy, so it’s a very direct reference. I also always thought Heathcliff was not entirely human, if you know what I mean. The mystery of his origins, the way he is adopted into the family. And both Juan and Heathcliff are Gothic heroes.

Gaspar was easier to create in many ways because he doesn’t need the grandeur. My objective with Gaspar was always: he’s a good kid, damaged but noble. It’s not just that he’s nice; he’s also responsible and attentive. How he got this with a father like Juan, I don’t know, but I wanted him to be like those kids who, no matter how harsh their upbringing, stay decent and fair. That’s where all the decisions come from, always with that in mind. Luis is a bit like him, too, as a grownup. When it comes to Adela, I never wanted the girl, just the house. This being a novel about heritage and ownership, houses were very important. In the second long part I needed a certain kind of house: a facade for a place that eats you. I realized I had written it already in a story. Since this was the early stage of the novel, I thought, “Why don’t I bring the girl in, too?” So, I brought both. And Adela opened the novel up a lot, in terms of plot and decisions and even explanations of certain things that happen. But it’s not the same character. I just kept the name and the house, but it’s a different person.

SB: Megan, I’m curious about your relationship with these characters. How do the references to other literary texts and Mariana’s previous stories inform your translation process?

MM: I’m always a little thrown off by that word “process.” I’m not really sure what it means or if I actually have a process. Process sounds so systematic, and I’m not sure I have a system, I feel like it just kind of flows. But I know that’s not really the question. I’ll focus on my relationship to the characters. I think that Juan, in particular, is a towering literary achievement. Mariana manages to imbue him with so many contradictory characteristics. He ends up being a character of extremes who is anything but black and white, but full of shades of gray: virile and strong but deathly ill, victim (of the Order) and victimizer (of Gaspar, to name one), powerful and powerless.

I’m particularly drawn to the bond between Juan and Gaspar. The opening section includes scenes of Juan tending to Gaspar when he has a crippling headache, and of six-year-old Gaspar talking Juan through a nearly deadly heart episode by telling him stories. These scenes illustrate the tenderness and care between them, making the moment when Juan hits Gaspar especially brutal. Later in the book, when Gaspar is older—and he and Juan have an even more fraught relationship—there’s one scene in particular where father and son go to scatter Rosario’s ashes that epitomizes what Mariana is able to do. It involves a ritual of letting go, and, as Juan and Gaspar renew their bond for a moment, they help each other and revert to almost a primitive state. It’s a beautiful scene. This is a fantastical book, yes, but the relationships in it are human in the best possible way.

SB: Mariana, thinking still about literary references, I’m curious about your relationship with the Gothic, especially the British tradition of the Gothic. You clearly draw a lot from the genre in this novel, including the significance of architecture, the presence of the supernatural, and death. I think the Gothic has been a really useful approach for a lot of contemporary Latin American writers, and I’m curious about how you’re applying and adapting the genre specifically to the Argentine context as a way of exploring Argentine history. Is this something you see yourself as doing?

ME: Yes. And I think there is a bit of a Gothic tradition in the twentieth century in Latin American and American literature: Ernesto Sabato in Argentina with Sobre héroes y tumbas, almost everything the Chilean writer José Donoso did, but the Obscene Bird of Night especially, and Juan Carlos Onetti, from Uruguay, who was a huge fan of Faulkner, as am I. So Southern Gothic, Latin American Gothic, and the Brontes are my canon. Also Anne Rice! Of the British, yes, I’ve read a lot. But let’s say I’m more influenced by the weird of Arthur Machen than Ann Radcliffe. Still, Frankenstein was important to me even in the making of Juan. Another body destroyed that turns cruel when rejected.

SB: I was fascinated by the constant sense in the novel that the dead are all around us. Obviously, this is a reality for Juan and occasionally Gaspar. But it also has implications for us as readers, making us think about how the dead always haunt us. Indeed, the English term “haunt” is key to the narrative in both Spanish and English, as articulated by Juan early in the novel:

He couldn’t find her. He could see that poor pregnant woman at the hotel, he could see hundreds of murder victims every day, and yet he couldn’t reach her. He had said to her once when she was alive, as a joke, imitating a character in a novel, Please don’t leave me alone, haunt me. He’d said it in English, “haunt me,” because there were no words in Spanish for that verb, not embrujar, not aparecer, it was haunt. She had laughed it off. He was supposed to die first—it was the most logical thing. It was ridiculous he was even still alive.

Mariana, could you expand on this notion of haunting and how you thought about it as you constructed the novel?

ME: Well, the interesting thing is that there’s no word for “haunted” in Spanish. The nearest would be “embrujado,” but that is bewitched. “Maldito,” but that implies a curse, although it’s nearer as it’s also rebellious. We also use “encantado,” but that’s enchanted. “Fantasmagórico,” another word in Spanish that is near “haunted,” is not exactly it either. It’s, well, phantasmagoric or ghostly. So yes, it’s a very important word and notion, but I think that importance speaks about how I work with the genre, which is to translate it. Not what Megan does, of course, but translation of a tradition and its lexicon that doesn’t necessarily mirror Spanish words or even descriptions.

SB: One striking thing to me is the way blood appears throughout the novel, as with the question of family heritage (blood ties), the role of blood in many of Juan’s rituals, and HIV. Mariana, could you talk about how you thought about blood as you wrote the novel?

ME: I thought about blood a lot, and the center of it is Juan’s heart disease. The blood pump that is almost broken, a family broken, sexuality menaced by blood and disease, also the vampiric idea of blood and contagion—family as a sort of contagion, as a virus, and the disease in the blood. Also, I wanted to write about AIDS because it was just the pandemic of my youth and a great source of real fear and discrimination that I feel is sometimes kind of forgotten.

SB: This question really is for both of you. Do you see translation as playing a role in the novel? Elements such as the use of Guaraní and English (in the Spanish version), Juan’s role as a mediator between worlds, the translation of messages (as with the demon), the notion of inheritance, and messages passed from one generation to the next all recall translation for me. I’m curious how you both thought conceptually about translation throughout this project.

ME: Yes, the Darkness that speaks in many languages and that nobody seems to hear the same way. Of course, Juan is the person who mediates but cannot translate. He is also part of a generational translation and distortion of what’s passed on. To me, writing in a genre that doesn’t have an extensive tradition in Spanish (yes, the fantastic, but I’m talking more about horror and the weird; they exist, but there’s no tradition, you can just name isolated writers or texts) implies a translation.

MM: One of the most fascinating instances of translation in the novel involves the scribes. During the ceremonies when the Darkness is channeled, a few people claim to hear its voice, and they write down what they hear. The Darkness’ words are then compiled in the Order’s holy book. The scribes are essentially translating the Darkness for posterity. But, throughout the novel, there is the question of whether they actually hear anything at all or whether they’re just writing things that come from their own minds. During the description of one ceremony, we’re told:

The scribes were writing, Tali saw them, but she didn’t hear anything, nothing but panting and that flapping of wings. What did they hear, those who heard the voice of the Darkness? Juan had told her once that they didn’t hear anything, it was all in their heads, that what they wrote was a kind of automatic dictation from their own minds.

What a metaphor for translation. How many of the words we translators write come from us, and how many from the author? Obviously, it’s impossible to quantify, and even asking the question seems to make readers a little nervous. If you take a negative view, you’ll get uncomfortably close to implying the futility of translation and, consequently (if looked at a certain way), of any communication at all.

Of course, no translation happens without the participation of the translator—I mean, without the translator’s interference. And anyone who has translated anything, I think, starts to feel how slippery words really are, how any word could be different, and no word really means only what we want it to mean when we use it. You start to feel like the idea or possibility of communicating something real is so remote and unreachable that it might be better just to stay silent. Words can be misinterpreted and misused, especially if the people listening don’t know how to listen well. And we want to avoid being scribes for the Darkness. Can we really trust the voices in our heads?

SB: Along those same lines, Megan, this is a multilingual novel. The use of Guaraní is fairly straightforward to keep as is, given it will more or less have the same function as a foreign term for Spanish and English readers (though, of course, Guaraní terms will mean something different to a reader in Argentina, Spain, and the United States). English language and culture, however, also play a significant role in the novel. How did you maintain the linguistic difference and foreignness of Guaraní while translating? For one thing, you use italics, which effectively creates a visual distinction. How did you come to this approach? Are there other techniques you employed?

MM: One character in particular, Florence, switches back and forth between English and Spanish. I used italics to set off the phrases she says in English. (You did the same in your translation of Jawbone by Mónica Ojeda.) I’m not sure it’s obvious to readers that Florence is speaking English; some people might read the italics as emphasis, but that’s fine too. It’s helpful to signal a kind of unevenness in her speech.

There was a point when I really wanted to include a glossary in the book. I’m very much opposed to footnotes, but I thought it would be good to define certain words I wanted to leave in but didn’t think readers would understand. Here are some of the words I might have included: mitaí, che, tereré, mate, angá, promesera, chamamé, Ka’aru, Nde tavy, chipón, chamiga, San la Muerte, payé, jangada, manguruyú, duende de la siesta, chipá.

A lot of those words appear in Tali’s section in Part 1. I thought a lot about creating Tali’s voice. I see her as free spirit, a little rough, down to earth, and very kind. She uses a lot of appellatives or terms of endearment, like “che,” which is Argentine and can be used for anyone, or “mitaí,” which is Guaraní and is more like “sweetie.” I sort of pictured Tali’s English as southern, and I had her use words like “honey” when she talked to Gaspar, in addition to “che” and “mitaí.” There’s a sort of music there, and my hope was that readers would understand the intention behind the words and hear the voice that said them, even if the words themselves were unfamiliar. I also had Tali curse more than any other character, I think. I wanted her to seem wild and exuberant but kindhearted.

SB: I’m interested in the scope of this novel. It’s significantly longer than Mariana’s shorter fiction. Mariana, how did you use this length to build this world and create such complex narrative layers?

ME: I needed the length. Some people think there are too many tangents and that it could be less arborescent, but I needed the length to make it believable. The novel is quite crazy. I needed a lot of description, time spent with the characters, even repetition. (A long novel can be Hemingwayesque.) When the layering started to happen, I gave in and said, “Let it be long.” So I think the length is justified. You know, I’m not the kind of writer or reader that thinks that a book should “work.” I think that’s totally a consumer point of view. I’m going to be pretentious here and say this is art, and you should try and experiment and fail because that’s how literature builds itself, not with a nice pretty, well done piece on top of the other. It builds with slim, great books and mastodonts and whatever the writer felt was needed to tell the story.

SB: Megan, were there techniques you used to navigate and contain such a long project?

MM: I had a very useful strategy called COVID lockdown, which forced me to spend a lot of time alone in my house. I don’t know if I could have gotten the book done so “fast” (that sound you hear is our editors laughing) if it hadn’t been for COVID.

In spite of my mystical ideas about process, I do have concrete time management practices I use in all my translation projects, not just epic ones. Translating a book, like any long-term project, can be daunting, and anything you can do to break it up into manageable pieces helps a lot. I keep track of how many hours I work every day and every week, and I keep checklists of pages and files where I jot down notes and questions as I’m working. All of that is useful for keeping up consistency and making projects more manageable.

SB: Megan, what sort of reading did (and do) you do alongside translating Mariana’s work?

MM: I had actually never read Wuthering Heights before. Can you believe it? So I read that during the time I was working on the novel. I also remember watching Paris is Burning and reading Larry Kramer’s Faggots. I think I did pull a few words from both, which is ostensibly what I was looking for, but interacting with those works was useful in getting a feeling for gay culture in the 80s during the AIDS crisis. I also dipped into some of the many poets Gaspar and Juan read, plus Eliphas Levi’s Dogma and Ritual of High Magic. You know, light reading.

SB: What is next for each of you?

ME: I’m writing three things now. I don’t know what happened; it’s like a fountain or something. A short story collection that is almost ready, a novel, quite Gothic but more contemporary (it will be from the 90s, not ending there, and probably a bit end-of-times but in a very Gothic, non-Last of Us or Mad Max way). Also, an essay on being a fan of a band, Suede. So I’m quite busy.

MM: I’m working on a translation of Juan Emar’s collection of short stories, Ten, to be published by New Directions (they also published his novel Yesterday last year). Emar was a Chilean writer from the early twentieth century, who was influenced by the Surrealists, and is kind of a cult author who never really got his due. I’m also finishing up a translation of La encomienda by Margarita García Robayo for Charco and working on some stories and essays for various outlets.

Sarah Booker is an educator and literary translator working from Spanish to English. Her translations include Mónica Ojeda’s Jawbone, Gabriela Ponce’s Blood Red, and Cristina Rivera Garza’s New and Selected Stories, Grieving: Dispatches from a Wounded Country, and The Iliac Crest.

More Interviews