The Point Is Not in Plot | A Conversation with Halle Hill

Interviews

By Kendra Allen

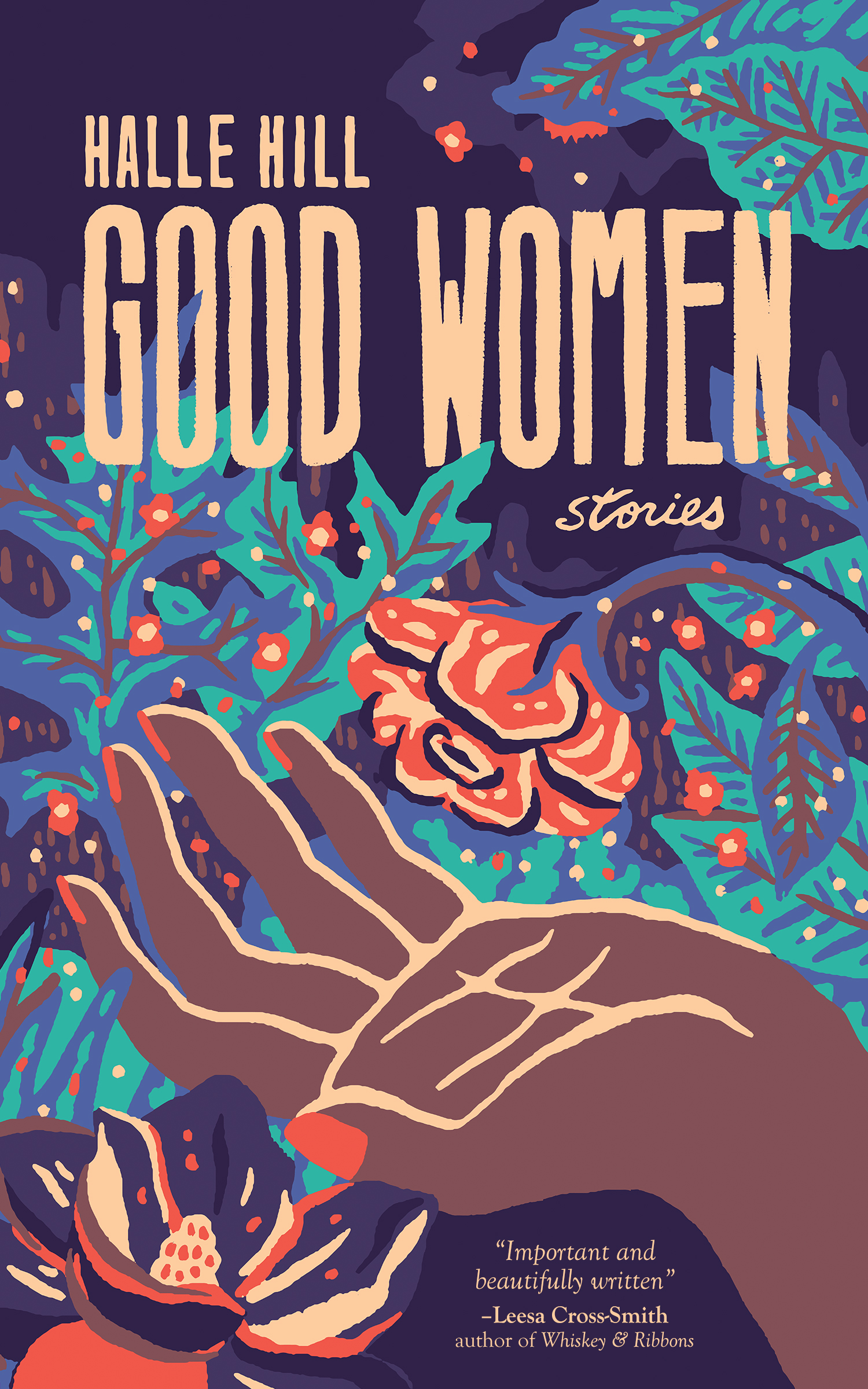

Halle Hill just has to say it. Two minutes into our conversation, she says something that makes me go “That’s a story!” And in Good Women—Hill’s debut story collection from Hub City Press—she tells it all with intention, through the lens of what it means to give birth; to babies, to books, and to self.

Good Women most times feels like a bare-boned installation of Black femme wanderings, wholeness, what it means to witness one’s surroundings while making self-informed decisions on where to go from there, and how all of it aligns with perception, vulnerability, and dreaming. It’s almost as if Hill is daring one to be brave enough to not just look but to see, so that you won’t ever forget again. Hill is a writer who takes her characters seriously, instilling them with humor, hope, and a humanness that is both full of clarity and confusion.

Through an astute attention to craft, she has a way of making the reader care to think more critically about the themes presented throughout in ways that feel more like a hug than a lesson. And after spending time hearing her speak about her process, it feels safe to say that Halle Hill also cares about your safety, your memories, and most prominently, your voice.

Our conversation took place over Zoom.

Kendra Allen: First things first: I find it fascinating how you were able to make every woman in Good Women so completely different. You write humans so vastly, which I think is way harder than most might assume it is—to steep each one into their own isolated worlds. I gotta pick your brain about plot because I never know its definition, and/or if it even matters. But I also didn’t study fiction, so I could be completely wrong. Do you outline?

![]()

Halle Hill: Absolutely not. I know very little about traditional fiction plot structures. I’m just gonna go ahead and put that on the table. I’m voice driven. I always think—get the voice right—and you can always clean it up and organize. The fiction I write—at least what I’ve written so far—doesn’t require this robust unfolding of plot. I’m not doing speculative or historical fiction, so plot is not my first thought. But I do think I’m trying to shape every story with intention, so I try to really cut down on wandering around. Everything has to come back to the essential promise of the story. I never want readers to feel like they’re wasting their time.

Halle Hill: Absolutely not. I know very little about traditional fiction plot structures. I’m just gonna go ahead and put that on the table. I’m voice driven. I always think—get the voice right—and you can always clean it up and organize. The fiction I write—at least what I’ve written so far—doesn’t require this robust unfolding of plot. I’m not doing speculative or historical fiction, so plot is not my first thought. But I do think I’m trying to shape every story with intention, so I try to really cut down on wandering around. Everything has to come back to the essential promise of the story. I never want readers to feel like they’re wasting their time.

I’m also always thinking—in my own traumatic experiences of racial prejudice—people really aren’t gonna give me time anyway. Urgency creates a feeling of timeliness, like when you know you’re talking to someone and they’re maybe 40% listening to you so you know you gotta get in quickly, and leave quickly, and maybe that way I can catch you and get you paying attention to me. I mirrored that sense of internal pacing in the book.

KA: So, thoughts, because what you said about having a sense of urgency when it comes to telling Black stories made me sad. Not sad, but somber, because I feel that as well. And what you said is true, but we also know it’s a mirage—it’s just our books are not packaged for the people we are writing books for, but that’s a whole other conversation. Anyways, I think you assist that eagerness with your dialogue. You don’t drag out a conversation or dilute the dialect. Reading, I felt that you knew what to say and when. What’s your approach?

HH: I think it’s personally that I do not care for too much dialogue; I like the idea of “saving your voice” within dialogue. One side of my family literally barely spoke when I would visit with them. They were “speak when you’re spoken to” people. It felt silencing, but also left an impression on me. When I’m writing short stories—it makes sense for people who are having dialogue—that it be essential. You can learn a lot about somebody by writing about them in observation, which is why a lot of dialogue in Good Women is more internal monologue than dialogue between people.

Because I am Appalachian, I get to throw things in that are real to what I heard growing up, and that’s a blast to play around with phonetically. My family talked to me a lot. I heard the same stories over and over again, and then when you’re older you have that epiphany when you’re like, “Oh, that was a warning,” or a really wise story. And although it burned me out, I wish I could hear that dialogue again. I value it now.

KA: Good as an adjective is so subjective, and I think society doesn’t even consider the word good at all when defining Black femmes. It’s typically something vaguely dismissive, like strong. But you chose Good Women as a book title. Could you talk a little bit about why and how it came to stick, what the word good means to you, and maybe what other titles you threw around?

HH: This is such a good question. You nailed it on the head. I’ve never seen good and Black women put together. The title, before I really was able to put the meaning together, actually just sounded good to me. I would say titles out loud in my car or in the shower to see “Does that fit?” Good Women felt nice in my mouth and sounded right to my ear. The other titles I considered didn’t feel helpful. I think you’re looking at a title to help it all make sense—especially in a collection—to give you a thread to follow. I’ll hear a phrase, and it’ll be running around in my head, and something’ll click and I’m like “That’s the title!” I think titles matter—a lot. To me at least. I write around the title. I’m totally title first. It leads me in a way.

At the same time, I was reading Lucille Clifton’s Good Woman while thinking about Good Women. We love her. The opening in the book is a poem from that collection. I’m always coming back to her poems, so I thought that’d be an easy way to mirror that title. But it is about—too—what do we think about: what does it mean to be good; especially as a woman? And I wanted the title to make a point about it being a struggle. You have to fight to be a good person. These women are pushing up against respectability politics, and I wanted to make a point that we all have to wrestle with our own sense of morality. And that’s typically messy, especially if you’re under constraints from any sense of marginalization. That’s why I chose Good Women. These morally gray women who make difficult decisions are at their base—and at their core—good people, even when they’re not doing good things.

KA: Good being a metaphor for human—because we don’t get the chance to do that—mess up and come back intact, or without judgment.

HH: Right. And how many books do we read where we see these types of white women characters and we say she’s “finding herself,” “coming of age,” “becoming.” But then immediately, when it’s Black women, the temptation is there to not have to wrestle with the discomfort of having to see them. If I was gonna write a book, I had to give Black women complexity. I couldn’t put them in the stereotypes. And if I did, I had to play around with why do people fall into these roles.

KA: What other books did you lean on throughout your life that led up to this book being made?

HH: I really loved The Girl Who Fell from the Sky by Heidi Durrow and have read that novel five or six times now. It was a guide for me and the first book that made me want to write. Woman Hollering Creek by Sandra Cisneros, of course. People like to talk about The House on Mango Street, but Woman Hollering Creek is the one.

KA: Get into the catalog!

HH: It’s . . . unbelievable. So, so, good. A staple for me. And of course, we love The Bluest Eye, another I had to depend on to help me understand how to write about children with complicated topics. It’s an untouchable novel. It’s so special. I got the audiobook this year of Toni Morrison reading it to me.

KA: She reads ALL of them!

HH: Different level. The voice. That book is just doing something I don’t understand. It’s beyond. I love anything Danielle Evans writes, and interestingly enough, I always come back to Halle Butler. She wrote these two novels Jillian and The New Me. They are absurd and perfectly wry. Butler’s writing is so smart. So funny. I read those a bunch. Sometimes twice a year.

KA: The Bluest Eye inspiration makes a lot of sense. I thought the way you honored the fullness of childhood was drawing the reader in, but was also devastating—in the best ways. What is your process of writing children vs. adults, and what made you wanna show the realities of what children are forced to see and cope with because of adults who refuse to unmask?

HH: This question got me. One, I think I’m personally in such an interesting place because I’m approaching thirty. I got some time, I’m twenty-eight, but I’m having to accept that I’m a grown-ass woman now, and that makes me reflective of my time as a child. I often wonder, “Where was I at seven? / What was I thinking at eight or nine? / What was I feeling? / What was my day like?” I wish I had known it was tremendously special. I write out of that space a lot. I think honoring children always makes me think of that scripture “out of the mouths of babes,” and their wisdom. I’m always in awe of the gift of children, and yet, we don’t respect children. Even in Black culture—at least in my experience—I feel children are very dismissed. Children are incredibly accurate in their perceptions of the adults around them. They’re aware, smart, and observant. We wonder why people act out as adults, when our culture has destroyed them as children. Even in the reports and studies about doctors believing Black people have a higher pain tolerance gets into this perception of Black girls as not innocent, inherently corrupt. It’s awful, that sense of being robbed of that childhood. I’m thinking specifically about the young girl in “Her Last Time in Dothan.” You wanna let a child in fiction speak in order to honor where they are in their age, but you don’t wanna infantilize them either. I kept thinking, “How do I tell this accurately?” And I sometimes would just sit and remember myself at that age, or think about what my mom or aunts were doing at that age. I’d spend a lot of time looking at my family’s faces when they were children in old photographs. I wanted to give the space for the children in this book to be valued as seers—as speakers—because they’re rich, and they’re right. And sometimes the truth they see is sad.

KA: I think it’s important because kids do experience grief and endings. That’s another thing I wanted to talk with you about: your relationship to endings, because I felt like a lot of these stories explore that. We see kids witnessing the demise of their parents’ relationships and lives; we see the end of sight; seasons ending, metaphorically and literally; and so much more.

HH: I strive to embrace endings when I’m writing, but I also value endings with no resolution. A lot of things don’t have the resolve humans crave, so every story can’t have an ending where somebody feels satisfied. I can’t write fiction authentically if I’m writing it that way.

I think, too, when you’re coming of age, how many of us have so many things that we didn’t understand as we grew? We lose our favorite grandparent but we’re taught in the church about eternal life and these ideals that they’re with you always. Then you lose that favorite aunt or uncle, and nothing you ever do helps you see them or speak to them again. You cope in very true and real ways that make you believe you’re still with their spirit. But on a day-to-day, it’s done. And again, I don’t think adults are always thinking about how a child is coping with that. Think about the first time you see a parent lie, or the first time you see a parent betray you, and you have to grapple with what does this mean about these people who you thought were kind of gods. So I think endings are very important, but rarely ever wrapped up with a bow, and I try to show that in the book.

KA: That’s so real, because the first you time really see your parent, you be like “Oh my god, what is going on, my entire life is a lie.”

HH: You’re like: “You’re acting out. I cannot trust you. You’re scaring me. Here I am taking care of you. I know your schedule better than you. I’m watching your patterns.” What is that? I’m eight.

KA: And in the same breath, you’re looked at as if you don’t have feelings, because you’re eight.

HH: And then the part I can’t stand is that I see you—but I also deeply, desperately, need you.

KA: *loud sigh*

HH: I think a lot of that is in the book too. Sometimes you have to churn through your life to be able to write well. Sometimes I’d be thinking, “Hmm, I sure can relate to some of my characters.” But I also hate how sometimes people think fiction is automatically autobiographical. But what people presume is not my problem. It’s more about a transcending truth for me than a literal one.

KA: For me, the emotional ties I felt throughout all stemmed from the first-person POV. I think it brings a vulnerability to the page and a natural tone to where the reader is both rooting for and yelling at the narrator for not only being in the space, but staying in the space. How did you know where to create nuance in—and for—your narrators?

HH: I play around with it. I wish I had a more systematic answer, but it’s somatic for me. Meaning, I look to my body to give me a response for what’s working or not. Like, “Eh, intuitively, that sounds awful, but this works.” Especially with “Skin Hunger,” which I’m surprised that a lot of people liked. But I feel like the first person is the only way you could have empathy for [the narrator] Shauna because you have to feel like she’s telling you the truth. Third person would make it feel like someone was observing her decisions, which would have made her feel deceitful. I can respect her struggles with truth if she’s at least telling it internally, so I knew first person would build trust.

KA: *whispers* Can I ask you about writing sex scenes? Not even about what you write really, but how do you know one is required? Because there’s a lot of romance in here. It’s a lot of romance with no love. Some romanticization of romance. But those moments where you actually do incorporate sex into those dynamics, how do you make that decision? And is it as cringey to type as it is to talk about?

HH: Ha! I’m blushing. I was having a bit of a delusional time here because I didn’t register that the book has so much sex in it. And the thing is, I rarely write about it explicitly. There’s a couple moments where I’m writing about the action, but a lot of it is implied. I don’t think that I wanna read a whole book with a lot of sex scenes because I think too much saturation loses its impact. But stories like “Skin Hunger” had to have it. And it had to be kind of erotic, a bit awkward, and disappointing, and silly, and realistic; it had to be kind of goofy.

A lot of the sex scenes are also paired with some other frustration or disappointment, and sometimes violence. But some of them are simply ridiculous. When I’m writing about sex, I really need you to believe it happened like that, and I need the reader to trust me. So I have to write about what you never wanna admit sex has been like.

KA: Your authenticity to place shines. Readers move through the mountains, sit on the Greyhound, and even eat something as regional as chess pie. Do you write such visceral details from memory, are you making them up, or are you visiting specific places in order to spark a memory? All of this is to say, is there such a thing as “method fiction writing”?

HH: I never thought of it like that, the idea of “method fiction writing.” I can certainly see that being a thing for writing about place, but I definitely write from memory. Which fascinates me. In a literal sense, our memories aren’t that accurate. But with fiction you can focus more on emotional truth, which I play around with. My good friend, poet Megan Denton Ray, taught me about keeping an image journal—something you keep in your bag with you, so when you see something peculiar, beautiful, mundane, plain, write about it in great detail. So I have journals filled with those dry logs that I can borrow and then embellish. I also traveled a lot while I wrote this book. I hopped around different jobs, which was intentional. I wanted to gather: to see as much as I could at this time in my life, including revisiting places.

KA: It comes to you once you get in the flow . . .

HH: Or, in my dreams! Dreams were so special while writing this book, because I would dream and then remember. I had this dream at the beginning of writing Good Women where I woke up in this banquet hall and every single ancestor I had was there for dinner, meeting up. I saw aunts and uncles and all my grandparents I hadn’t thought about since I was a child. I could see everybody and their faces. Dreams like that kept coming while writing, dreams where I’d remember places I had been. I’d wake up and try to write them down, and that really helped with writing place too.

KA: Did you always know while writing that you were writing a book? Or did you just look up one day like, “I got 200 pages of stories that fit together”?

HH: I guess yes and no. I always knew I wanted to write a book. But I totally didn’t think it was possible. I was not the it girl in my MFA, but I wanted to make something of my time in the program, so I pushed myself hard when I wrote my thesis. I knew I wanted to write short stories. I kept working at it, but I also thought maybe there’s a 1% chance this will make something. I sold my manuscript partially, so some of these stories are six and seven years old. It really was about rewriting things that I’d already done to match the quality of the newer ones.

KA: 1%?!

HH: I don’t know! I was nervous!

KA: I get it, I get it. I’m always saying how sequencing a collection is a class that needs to be taught. I think this book could easily be a part of that curriculum on how to do it right. I also listened to your playlist for the book, which is just another testament to what I’m talking about. What was that process like for you to order these stories in a way that organized the chaos—because lemme tell you, you do drama well.

HH: I knew that I wanted to come out with “Seeking Arrangements.” It’s on the Greyhound, and it starts with that knowing of, “We’re gonna take each other somewhere.” I always knew that would open the book. My incredible editor and press really helped, of course.. They had great insight on how to do it, because all these stories are talking to each other. But there has to be a strategy. You don’t wanna front-load it or bottleneck it. You wanna do it to where it flows and fits and pulls readers along. Each story is a patchwork piece of the larger, whole story.

And I didn’t want anything to feel gimmicky. So it’s like, “How do you write with the shock, but not the gimmick?” Because it’s genuine. All of these stories could happen, and probably have happened. So I kept trying to think about how pacing could hold all of these stories right.

KA: Restraint is such an underrated skill. It’s a hard skill to practice, because writing is hard, and we don’t want the words to go to waste. But sometimes your best words have to be eliminated to serve the story, or the structure, or the sequence, or whatever, but you know how to write a lot to get a little.

HH: You don’t have to give everything. Again, that concept of saving your voice. I held many stories back for a later time. Because there’s time. There’s more to write, there’s more to explore, and I think restraint is something we don’t value. I’m constantly frustrated with how much pressure I feel for efficiency and mindless productivity. The banal push for efficiency and immediacy is gonna destroy us all. That’s the pleasure and the pain—I hate that phrase—it’s so goofy, but that was the pleasure, and the really hard part of writing this book: accepting that it was going to take years. It’s really nice to feel that you did something to the best of your ability without worrying about how someone else is gonna receive it, or if it’s good enough. It made me feel good enough to know I put all of my best into trying to do this. And that’s something that is not efficient. Carving the book down led to brevity. I didn’t want there to be a lull in consistency. And I like a short book. Culturally, I feel like the short story was making sense for me as a Black person. I don’t have that WASP, traditional, American thread where I do this, I go here, I did that, I got married, etc. It’s been a patchwork of trying to find my place in life.

And I’m not honoring the women in this book if I’m just stretching it out to make a neat and tidy story. And, at a certain point, the stories are no longer about you. They tap into something else. I’m a Sag, and when I’ve had enough, Ima say it. It just has to be said. But restraint is self-control. I like when I read a book and see a sense of economy: paring down to what’s essential. I had to remind myself, “I don’t have to explain this. The book. The women. None of that here.”

KA: Yes! It’s like a type of mothering—to always accept the onus of over-explanation. I think something else powerful that you do is create characters who come to the conclusion that they don’t want or need to be a mother. At least not in this “birth a baby and raise it” way. Yet they also accept forms of mothering from outside sources, such as sisters. Both of these things we see in “Skin Hunger” —which, the stress—but it’s one of my favorite stories in the collection. What stood out most about it is the foreshadowing of blatant racism that takes place in a sort of if you know, you know kinda way. These markers you write throughout to show harm being performed as help. It’s very gentle. Very subtle.

HH: I think what’s interesting about Shauna thinking she shouldn’t be a mother is that she admires her sister, who had power in her choice. Or at least it let Shauna know she couldn’t be a mother in this environment, because it would destroy her child. There’s also a fetish point here for a biracial child. These different layers being asked of: at what point is a Black woman desirable? Because there’s also these adopted Black children toted around with bows in their heads to show off money. International adoptions are extremely expensive. I’m not making any claims about people who engage with these really expensive adoptions, but in this specific story, it’s also clear that these people are looking at Black people with varying degrees of desensitization. There’s a ranking, even in her marriage, and even with the “fling” preservationist man who appears later in the story. I wanted Shauna to get her lick back, but it just was not possible. I couldn’t beat the reader over the head with it; I just had to let the story show itself. I think the reason the story is so uncomfortable is because everyone knows it’s true. So Shauna makes a bad decision—but when are we gonna let a Black woman mess up?! When can they be complicated? When can they be “bad”?

KA: Which is a heavy theme throughout the whole book. I keep thinking of the word endurance when I think of these characters. But not in the way we use it to dilute a plight. I say endurance as in like a haunting, or a war within oneself. Which we see culminate in the final story, “How To Cut and Quarter.” What did that feel like for you to write through the endless forms of mothering we receive throughout our existences, and did you ever fight against this theme’s appearance throughout the writing of Good Women?

HH: Forever I thought this book was about fathers. And then I got smacked upside the head. Had to wrestle with it being a lot about mothers. But I also think sometimes the mothering here is in response. To brutality. To fear. Response as preservation. But also, some of it is mothering out of protection, out of inspiration, out of love, out of care, out of gentleness. There’s some tender times, where I feel like I see these women be so subtle and gentle with their love— which is one of my favorite types of love. How do you make space for that, and show mothering that way? I’m not a mother, but that doesn’t mean I haven’t done my own mothering. I’m fortunate to have a strong relationship with my mother, but I also deeply empathize with people who have struggled with their relationships with their mothers. Even the archetype of “mother” is prevalent in everything.

So I had to draw on that, and I think a lot of these women are trying to mother themselves as well. It’s makes me think too—because so much of the world is really excited about therapy-speak, we’re always like, “mother your inner child,” “boundaries with your mother,” “how to heal from the mother wound.” Or like—“I Cut My Mother Off: 10 Ways to Deal With a Toxic Family Member.” I think a lot of that is actually pretty powerful, and it’s important in order for some people to move forward. But I also wanna see a healing journey for a woman where we see the delicate space between accountability and annihilation. Where’s the story for the women who love their moms and also struggle with how they were raised? Or where’s the one where we can talk about people who we know didn’t have the tools but wanna make some kind of quiet space to say, “You could’ve done that differently.” I need to see that nuance. I don’t need ten tips to deal. That’s not the way life goes, and I think a lot of the women in this book are navigating that through whatever mothering season they’re in. But I also still believe mothers are our greatest gifts in this life, so I needed to figure out how I could write about that with reverence.

KA: You definitely did. I can’t wait to share this book with so many people. Ok, last question: Are you proud of yourself?

HH: I am! You don’t wanna get a big head, because I’m still blown away that this even happened, but I am proud of myself. Because I know I put the work in. You know what I mean? Actually. I know you do.

Kendra Allen was born and raised in Dallas, Texas. She loves laughing, leaving, and writing Make Love in My Car, a music column for Southwest Review. Some of her other work can be found in, or on, the Paris Review, High Times, the Rumpus, and more. She’s the author of a book of poetry, The Collection Plate, and a book of essays, When You Learn the Alphabet, which won the 2018 Iowa Prize for Literary Nonfiction. Fruit Punch, her memoir, is out now.

More Interviews