Reviews

Lost in a Desert Fever Dream

A Neo-Baroque Carnival

Art Monster

We See What We Want to See

Her Story Must Be Told

The Absence of Choice

Dark Hilarity

Teaching a Wound to Speak

How Do You Desire to Be Haunted?

A Wild Danse Macabre

The Horror of the Quotidian

Of Monsters and Women

What Was Found and Who Was Lost

Birds Are Also Free to Walk

Pure, Entertaining Thinking

Master of the Minimal

In Praise of Messy Creation

Unsafe, Unthinkable You

Pornographic Noir

The Most Dangerous Cudgel

Old South, My Ass

Stories We Don’t Want to Hear

Reaching New Heights

Capitalism and Culpability

The Noise an Object Makes

Semiotics for the Global Damned

Natural Ecstasy

The Glory of Cleaning Toilets

To say that Rodrigo Fresán’s recently completed triptych novel[1] is an ambitious book is to come up woefully short. To say that it contains all his books, themes, songs, and films doesn’t cut it either. Even if these three books are an infinite triptych, where all the books fit (all those he’s written,[2] making cameos with altered titles and characters, and many of the ones he loves and admires) and where the cast, the themes, and the situations mutate in a game of endless variations, these three books also bring their own ghosts, appearing and disappearing, from one part to the next. A haunted house that’s also a beach house, a written house, a museum/time machine, a convent, and a memory palace. A triptych of books that contain one another, that sing to one another, that invent and dream and remember one another.

And the effect is striking.

Because here Rodrigo Fresán—who tends to make reiteration a key element of his style—takes the pirouette to moving depths. Returning to scenes (like “That Night”), to reflections on songs (like “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” or “Big Sky”), to quotations that are repeated and evoked (from Dracula, from Slaughterhouse-Five, from the works of Francis Scott Fitzgerald or Nabokov to name a few), the reader is left with the feeling of always remembering. Because as we read, reading along, we’re also rereading. Even if the reader has never held a Fresán book in her hands (and if she has, the experience takes on immense proportions), in his triptych—with the play of looping references, of recurrent paragraphs, characters, and anecdotes—the author recreates his entire universe and, in that way, turns the act of reading into an act of memory. His use of repetition is also interlaced with an obsession with Glenn Gould’s performances of Bach’s Goldberg Variations and a fascination with childhood, that period when we first get infected with the virus of reading and when readers find more joy in felicitous repetition than in novelty of plot. [3]

The play of echoes is so marvelous (and it reaches an incredibly intricate level of detail/artistry) that even the ending of The Remembered Part—which comes as a surprise, a new kind of song—is also a memory of something that came before.

A memory like a dream.

A kind of ventriloquism.

Maybe a new alien part.

And here we go again.

To review the marvel.

VAMPIRE NOTES

The Parts Triptych is a work of monumental scope (2,001 pages in the original Spanish edition), comprising The Invented Part, The Dreamed Part, and The Remembered Part and written over the course of ten years. It’s a repository of stories (many! so many!) beyond those of its main characters (or of all those its characters might imagine, dream, and remember) and an exploration of the primary materials all writers draw on: invention, dream, and memory (and the close relationship between them) in all their beautiful complexity. But also, in the words of this third volume, this triptych is about “books whose subject was as exhausting as it was inexhaustible. The most transgressive subject of all in times that were dragging along and flying by. Books about reading and writing. About reading and about writing and about reading it all again when you could no longer write, when you became both victim and victimizer of a terminal or interminable block.”

Because in this triptych we’ve got a writer—once a nextwriter, now an exwriter, always a readeriter—who, very much despite himself, can no longer write.[4] Very much despite himself because this exwriter has a lot to tell: because he has a secret that torments him, parents who disappear/disappeared/are always about to disappear, and a sister, Penelope (a reader forever possessed by the spirit of Wuthering Heights and also, in part, by her bizarre in-laws, the Karmas), who becomes the author of bestsellers while he, in part and in some Part, becomes executor of her literary estate; because he has something resembling a disciple-nemesis named IKEA; and, finally, because even though he can’t write, his head—always inventing, dreaming, and remembering—can’t shut off (and in The Remembered Part, in a distinct typography, we read: “And the saddest and most tormenting thing of all: one stopped writing, yes, but one never stopped thinking about writing, about what one would write if one were able to put it in writing”).

So we have an outpouring of stories that could be written, that are thought and hurriedly scribbled in a notebook while awaiting a diagnosis in a hospital, that are recounted on interminable flights, that are hallucinated after drinking the milk of a colossal green cow in a diamond-strewn desert—another double or mirror scene of those siblings described in The Invented Part as continuities/continuations in orbit: “. . . like astronauts outside the space shuttle, wearing a single smile (there was no doubt they were brother and sister) that began on the mouth of one and ended on the mouth of the other.” Stories that might just be refracted in all those crazy diamonds. Inventions and dreams and memories and a profound insomnia in the mind of this precarious writer, this writer who seems to live in his notes, in his biji notebooks, in his favorite books, and with this, the whole apparent, and apparently reliable, order of time ends up coming undone.[5] Because the time of dreams and memories, the time of books, is a different time, or as it says in The Invented Part: “. . . that continuous present where the past and the future pass away. A time that passes simultaneously, and that you enter and exit the way you enter a house where, having once resided there, you still live. A house that looks more and more like a museum.”[6]

ALL TOGETHER NOW

The reading of The Parts Triptych becomes complex and aspires to an impossible simultaneity (the exwriter himself has the harebrained idea of entering a Swiss particle accelerator so he can be everywhere at once and transform himself into the great rewriter of reality). That’s why, I think, in interviews, Rodrigo Fresán refers to these three volumes as a triptych. Not a trilogy that advances, but three parts that function simultaneously: all times at the same time, like the song of his beloved Beatles “All Together Now,” like the Tralfamadorian books of Vonnegut.[7] A kind of Aleph in 3D and Dolby digital surround sound. A triptych—I think of Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, where you can see so much and everything at the same time—where all the stories and characters coexist, like a collage or like the last option on a multiple-choice test, emphatically marked with a brilliant X: All of the above. Or as we read in The Dreamed Part: “A book that was all the books that a book could possibly be.” And also, now, in The Remembered Part: “Because, after all, that is what his books were all about: about the inexact, nonfiction science—but nevertheless increasingly alien discipline—of reading and writing; about another form of interplanetary voyage and cosmic mutation and interdimensional wormhole, but with far subtler and harder-to-discover technology.”

Fresán tends to mock—and in this triptych he does so more than once through the mouth of the narrator—the realist aspirations of realism: its detailed structure, how it explains the world in a clean and coherent way, when reality is far more chaotic, with many things happening at the same time, when imagining other things, other worlds, might just be the realest thing we can achieve. Thus, this particular In Search of Lost Time (another huge reference/obsession of these books) of Fresán’s becomes a vertiginous search for lost times (plural, all times at the same time), and for that reason, it makes for a challenging yet incredibly rewarding reading experience. An alien book written for an alien reader (like the alien films of Kubrick) or a reader who can breathe underwater (we read in The Invented Part and reread and remember in The Remembered Part: “If—as the author of his parents’ favorite novel said—all good writing is swimming underwater and holding your breath, then he liked to think that all good reading was opening your mouth underwater and discovering that, all of a sudden, you could breathe. That’s how he’d liked to think of his readers—as terra-firma and quicksand amphibians—back when he still wrote a great deal to be read by very few”). A reader who could double herself and continue reading The Parts Triptych while running off to read or reread Nabokov’s Transparent Things or Ada, or Ardor, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night, stories by Donald Barthelme, by John Cheever, by Philip K. Dick, and so many others. A reader like the readers who also appear in this triptych, those rereaders who return to the books that have possessed them whenever they can: like the exwriter with Dracula or Tender Is the Night, like Penelope with Wuthering Heights (and how marvelous it is, in The Dreamed Part, when we revisit that novel and that other haunted house, how radioactive that love of books is, how at home, indeed, one feels reading others reread).

A book that could also (and so well) be the best toy.

Because in this triptych, toys abound, in multiple incarnations: Mr. Trip, the defective windup tin traveler who walks backward (and who, in the different stories, is bought, changes size, belongs to different characters, is sold in an airline magazine, and adorns, cool as a cucumber, carrying his suitcase covered with stickers and always with some variations, the covers of all three books), the toy soldiers of the Brontë siblings, the sled from Citizen Kane, the lemur from 2001: A Space Odyssey, the little wooden horse from the new Blade Runner. Which reminds me of a quote from Bento’s Sketchbook by John Berger that I like a lot and that goes like this: “People hold books in a special way—like they hold nothing else. They hold them not like inanimate things but like ones that have gone to sleep. Children often carry toys in the same manner.” And in The Remembered Part, again we see the exwriter as a boy, along with his little sister Penelope and his uncle Hey Walrus, who has given them books that they carry tightly under their arms as they wander a dark city that will only get darker throughout “That Night,” which recurs again and again. “That Night” that the exwriter must fend off by recounting things, more things all the time, like Scheherazade in One Thousand and One Nights, to stave off death. Or as Fresán would say (a variation on Nabokov’s “More in a moment” in Transparent Things): “Details coming up.” Always more details, always coming up.

Or also: we always return to childhood; the world always ends again. Some world.

Sometimes with the sound of a phone ringing in the dead of night.

Because this triptych—which contains so much, saturated in constant references—also hides a sad song.[8] Because this triptych is also an album about absence. An album of long songs divided into many parts. Like Pink Floyd’s Wish You Were Here. An absence that’s a strange kind of all-seeing eye, like in the Kinks’ “Big Sky.”

In this triptych, absences and disappearances abound: in The Invented Part, the writer is missing; in The Dreamed Part, it’s his parents; and in The Remembered Part, it’s Penelope and her lost son. People are missing and missed, for a long time or a short while, and those missing people haunt these stories and notes and references like indefatigable ghosts. Vampire ghosts who speak/write for themselves, interjecting their voices into the text in a different typography. Because throughout the three volumes we have interventions of sentences and paragraphs and pages in American Typewriter, a font that sometimes reads like the comments of the writer or of his sister from the Beyond/Here/Somewhere, sometimes like the ghost of (North) American literature that recognizes itself in so much of what (and of how) Fresán writes, sometimes like the voice of memory, of guilt, of madness, like a writer who becomes a reader to reread and revise himself as he writes or thinks (invents/dreams/remembers), or—the image that always comes to mind as I read—like the murmuring of Glenn Gould that accompanies his performance of Bach’s Goldberg Variations. Some Fresán variations of Nabokov/Fitzgerald/Brontë performed by an omniscient narrator who isn’t content to merely resemble a first-person narrator (and who describes himself as “a narrator in the most first of third person”), but who is—and how could he not be?—multiple possible first-person narrators at the same time, and who doesn’t only know and see everything that happens, but also imagines different possible versions of everything that happened, happens, will happen, or could’ve happened. And among all those possibilities, there are moments of laughter and of dazzling brilliance, and more than one that will break your heart. A DVD/Blu-ray director’s cut with the voiceover of the director and actors accompanying/commenting on the scenes on the screen. A writer and all the voices that he writes and that live in and with him. A writer like a haunted house that sometimes makes us ask: Who is more a ghost than the reader of a book? Who is more a ghost than its author?[9]

In his triptych, Fresán has constructed a time machine inside of which anything can happen: alternatives, plotlines and meta-plotlines, versions and variations. His characters are infected readers who love their books more than anything,[10] whose parents are always getting lost in Farawayland,[11] and who always find new family in oddball characters like Uncle Hey Walrus (who gives the nextwriter and Penelope vital books, takes them to see films that mark their lives, and refers to them as “my little orphans of living parents”) and in the novels that make them feel at home when they open the doors of their lives to them (and we read [and read again] in The Remembered Part: “Literature like that vampire you—dazzled by the possibilities of his power—open the door to and invite in, suspecting all the while that from then on it’ll be impossible to contain him”). Because the exwriter decides to not have a family and to embrace his solitude (though there is Ella, another ghost of so many novels past, perhaps something akin to that “she” Bob Dylan or the Beatles sing to in so many of their songs; but also, as you read in The Dreamed Part: “For good or ill, writers on their own are never really alone: they’re accompanied by other writers who are also on their own”). And Penelope—who is pretty much abducted by the Karmas (that other great alien family-dimension of Fresán’s work, an echo of the Mantra family from Fresán’s novel of the same name)[12]—finally escapes to tell her tale in another way, filtered through her beloved Brontës and her notebook, Karma Konfidential, also written in that same ghost typography.

It’s hard to write about Fresán’s work without falling prey to his referential mania, without filling the pages with parentheses.[13] It’s hard to not want to underline everything and include it in one thousand and one quotes. It’s hard, too, not to feel like a ventriloquist and to speak about the style, plot, and structure of these books in their own words. Because everything is already here. Because Rodrigo Fresán always already wrote himself better, and before.[14] And so all that’s left is to trace the tracks, to follow the yellow-brick road and off to see the Wizard. Because to read a book by Fresán is like waking up inside a library (that, like the dinosaur, is still there, will always be there).[15] In an amusement park for addicted readers, those who not only let in the monster but who are impatiently waiting on the other side of the door, hoping it will come soon. Those amphibian readers ready to dive in over and over, to try to breathe underwater. Because in this triptych, literature is a galaxy or an organism in constant, and sometimes monstrous, expansion and mutation, a party à la Gatsby where there’s talk of the Gaboom, of Masterpieceland, of the Proustophone, of Literature of the I, of Alka-Seltzer novels or novels with training wheels versus no-hands novels. A triptych in which opening a book (or listening to a song or seeing a movie) is a way to transform the world. Some world. Irredeemably.

And The Remembered Part takes us on a dazzling journey through all of that and reveals the answers to many questions while leaving others, happily, cloaked in mystery. Making pilgrimages to Proust’s house, Billy Pilgrim’s tomb, and Nabokov’s office, or revisiting 2001: A Space Odyssey or Martin Eden or Blade Runner, in a time that’s all times and that’s measured in airplanes and in lists and in multiple-choice tests and in long, multi-part songs. A triptych that reminds us that after a devastating expansion comes the contraction; that sometimes the maximal odyssey, after monsters and misadventures, is to return home.

And you finish reading all of this and all you can do is give thanks. Thanks for “those endless days, those sacred days” that we spent reading it. A deeply grateful thanks, sure, but a thanks to which the reader’s mind is already beginning to put a little Oscars’ tune to hurry it along, so she can dive back in. And, yes, remember.

And so, with Fresán, we’re always rereading.

Not to look for answers or to find ourselves.

To lose ourselves.

Happily.

More and better every time. ![]()

[1] This article was first published in the Colombian magazine Libros & Letras in February 2020, shortly after the publication of the Spanish edition of The Remembered Part, under the title “Había otra vez: Las partes de una cancion” [“Once Upon Another Time: The Parts of a Song”]. Almost three years later, this corrected and expanded version is here to celebrate the publication of the final installment of Fresán’s magnificent triptych in English.

[2] To date, in Spanish, Fresán has published twelve books of fiction: Historia Argentina, Vidas de Santos, Trabajos manuals, Esperanto, La velocidad de las cosas, Mantra, Jardines de Kensington, El fondo del cielo, La parte inventada, La parte soñada, La parte recordada, and the most recent, Melvill, published in Spain in January 2022. In English, there are only (I say “only” with regret and hope that more are translated soon) Kensington Gardens (translated by Natasha Wimmer) and The Bottom of the Sky, The Invented Part, The Dreamed Part, and The Remembered Part (all translated by Will Vanderhyden; The Invented Part won the Best Translated Book Award in 2018). Your humble reviewer has read all of them (multiple times) and takes all of them into account (invites them in, opens the door and windows for them) in this review.

[3] As, for example, the protagonist of Kensington Gardens (a novel in which, in a way, children’s literature is a protagonist, a reflection on the life and work of J. M. Barrie, author of Peter Pan, interwoven with the story of Peter Hook, a children’s writer best known for creating the saga of Jimmy Yang, a boy who time travels on his bicycle) says: “Fortunate are those who read as children, because theirs may never be the kingdom of heaven but they’ll be granted access to other people’s heavens, and there they’ll learn the many ways of escaping their own hells with the nonfictitious strategies of fictional characters.”

[4] According to the definitions in these books, a nextwriter is someone who will become a writer, a readeriter is a writer who is a reader who writes more than a writer who reads, and an exwriter is a writer who no longer writes.

[5] In Fresán’s work, orders that disorder the world abound. Like in Mantra, a novel he was assigned to write about Mexico City, in which an entire section is organized into a strange encyclopedia, in alphabetical order, that refracts and amplifies the chaos of the city, of the story being told, of literature and of life, to the delight of readers.

[6] Fresán has mentioned in interviews that writing his body of work—of stories and references in constant conversation—is like adding rooms to a single house. And houses, as well as other buildings (like asylums or memory palaces), abound in this tryptic and in his other books. Here, also, they echo Wuthering Heights (another book about/with houses and named for a house; Fresán calls it a “real-estate fiction”), which functions as one of the big hearts of The Dreamed Part, and they also echo the gesture of inviting a vampire to enter our house, which in Fresán’s work becomes a double gesture of letting a book, or literature, enter our lives.

[7] Vonnegut says of Tralfamadorian books in Slaughterhouse-Five: “We Tralfamadorians read them all at once, not one after the other. There isn’t any particular relationship between all the messages, except that the author has chosen them carefully, so that, when seen all at once, they produce an image of life that is beautiful and surprising and deep. There is no beginning, no middle, no end, no suspense, no moral, no causes, no effects. What we love in our books are the depths of many marvelous moments seen all at one time.”

[8] In Fresán’s books there always appears, mentioned in passing or in a starring role, a mutating city called Sad Songs, which is also Canciones Tristes, Carminia Tristia, Chansones Tristes, Rancheras Nostálicas, Melancholy Rancheras, and Cánticos Sombríos, depending on the novel. A displaced homeland where the author’s obsessions—childhood, memory (and, with it, memories of film, music, and literature), and death—wander and plant their flag. A city that sometimes we never even arrive at, because the events transpire just “on the outskirts.”

[9] This footnote comes from the future. The future of Fresán’s next (for all of you) book that I hope reaches your hands soon. Because in Melvill, Fresán repeats the gesture of ghost voices that are modified and erased and rewritten. The voices of a father and a son. And Melvill, or at least the idea or note about this novel about the father of the writer Herman Melville (whose surname didn’t initially have that final e), first appears in the pages of The Remembered Part. So again, with Fresán, when we read, we remember.

[10] People often say that Fresán always writes about writers, but to tell the truth, it strikes me that in his books, the writers are, above all, awed readers. Readers who become writers who’re always rereading the same books (Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night in The Invented Part, Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights in The Dreamed Part, and Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey in The Remembered Part, to name a few). A body of work that turns the reader into the protagonist and in which characters are defined, first and foremost, by what they read. And what they read marks them, deforms them, inundates them. Yes, because to read Fresán is always to reread. In his books, his characters are never alone. Or not really. They all come loaded with their own books, their own, exceedingly personal, house of ghosts that allow them to read their reality (or, as it says in The Dreamed Part: “Rereading is like seeing real ghosts. Generous ghosts who believe in us”). Fresán’s characters are readers, and they love their books more than their families, maybe even more than themselves. With a furious love that transforms everything in its path and that’s the only thing that appears not to change, in a world where everything changes. More than fiction, infection: characters infected by stories—their stories and the stories of others that feel like their own. Because when reading, they might discover that someone else has written them better than they ever imagined themselves. Because if they learn their favorite novel by heart, maybe the hurt of their reality will finally leave them in peace. Thus, for example, the protagonist of Kensington Gardens says: “This, I think, is always the function of our favorite books, our bedside books, the books we read to help us sleep, the books we pick up again as soon as we awake: discovering in them that someone’s written us much better than we could ever write ourselves. And knowing that this book—a book that many might’ve read but that was intended for just one person—is waiting for us somewhere, that all we have to do is go in search of it and find it.” And the thing is, in novels where parents always disappear, or die, or go off globetrotting, or are about to abandon their children, books become a new form of family. And, also, a new form of reading family.

[11] In The Remembered Part we read: “Farawayland was the kingdom where parents went to think and fantasize—to invent and to dream—that they didn’t have any children, to forget that they had children. Farawayland was the magical realm where their parents didn’t remember that they had been and continued to be parents.”

[12] The Karma family, in this triptych, functions as a rewrite of the Mantra family. A clan of extravagant characters, intersecting on more than one occasion with historical events and personas.

[13] In Fresán’s work, parentheses function like other worlds inside this world. Like the parentheses we form with our hand when we want to tell a secret. Or as we read in Melvill between parentheses: “(one of my favorite orthographic marks, I don’t think there’s any need to point it out at this point; those parentheses that let you take some distance closing in a little bit more, one on each side, like hands in prayer and containing the space in which, together and at the same time, sin and repentance commune).”

[14] Some examples of this, in The Invented Part: “. . . one of those books that, with time’s passing, time’s running, charges you the entrance fee of learning everything all over again: a brand-new game with rules and—you’ve been warned—a breathing all its own, a rhythm you have to absorb and follow if your goal is to climb up on the shore of the last page.” In The Dreamed Part: “Three books configuring a trilogy, not linear and advancing, but horizontal and happening simultaneously (all times at the same time, like the time of that cosmic voyager untethered from time).” In The Remembered Part: “A book that, in practice, would contain its theory and whose plot would reside in its style. A book whose main character would be none other than the language the book spoke (one language but with linguistic variations and rhythms and phrases that distinguished what was invented and what was dreamed and what was remembered).”

[15] Reference to the story “The Dinosaur” by Augusto Monterroso, supposedly among the shortest stories ever written: “And when it woke up, the dinosaur was still there.”

María José Navia is the author of two novels, four collections of short stories, and one children’s book. She holds an MA from New York University and a PhD from Georgetown University, and currently works as an assistant professor at Chile’s Pontificia Universidad Católica. Some of her work has been published in English in World Literature Today, Latin American Literature Today, and The Brooklyn Rail.

Will Vanderhyden has an MA in literary translation from the University of Rochester. He has translated the work of Carlos Labbé, Rodrigo Fresán, Fernanda García Lao, and Juan Villoro, among others. His translations have appeared in journals such as Granta, Two Lines, Slate, The Arkansas International, Future Tense, and Southwest Review. He has received fellowships from the NEA and the Lannan Foundation. His translation of The Invented Part by Rodrigo Fresán won the 2018 Best Translated Book Award.

If Memory Serves

Our Eternal Debasement

An Islander with All Her Muddles

We Only Do What We Must

A Massive Living Mural

A Surreal Delight

The Workshop of an Iconoclast

Weird, Bloody Magic

The Bitter Perfume of Mystery

A Special Kind of Rage

The Art of Stealing

That Weird and That Good

Portrait of an Unknown Artist

A Hybrid Literary Beast

Waiting for Mario

Lunatics and Lost People

A Portable Solitude

Portrait of a Creep

Authors Behaving Badly

The Horror of the Inexplicable

The Whole Twisted Thing Is True

The Costs of Paying Attention

Red Dust: A Novel by Yoss

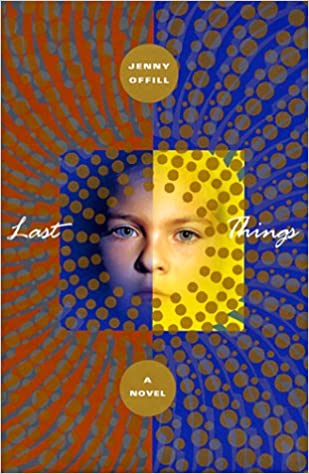

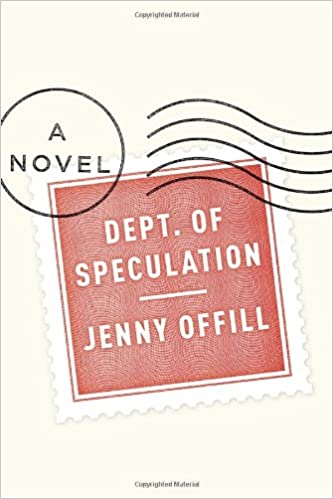

Jenny Offill is the rare contemporary writer for whom my five-year-old son and I can share an appreciation. That’s because, in addition to being a widely praised novelist, Offill has authored a handful of picture books that meet the standards set by a half-decade’s worth of pre-bedtime reads. While there are plenty of (adult) novelists who also write for YA and middle-grade audiences, the list of those who dabble in picture books has to be shorter, I reckon. Offill is the one of the few I’ve come across in my time browsing the aisles of the children’s section of my local library trying to find something, anything, please, to break the spell cast by Supertruck and Goodnight, Goodnight, Construction Site. Any parent knows it’s as difficult to pin down the secret to a successful picture book—one enjoyed by reader and audience alike—as it is to pin down the secret to a successful novel. But when one works, it’s immediate and obvious. Offill’s are like that. While You Were Napping (illustrated by Barry Blitt, of New Yorker cover fame) and 17 Things I’m Not Allowed to Do Anymore (illustrated by Nancy Carpenter) are our particular favorites. These titles, like all of Offill’s picture books, share two key elements: vivid illustrations (although one might take this as a given, it’s not always the case that a good picture book has, you know, good pictures) and humor that has both adult sophistication and juvenile appeal. For example, 17 Things I’m Not Allowed to Do Anymore has its narrator, a spunky elementary-age girl, list some of her ingeniously naughty ideas and their resulting prohibitions: “I had an idea to glue my brother’s bunny slippers to the floor. I am not allowed to use the glue anymore . . . I had an idea to freeze a dead fly in the ice cube tray. I am not allowed to make ice anymore.” As the parent chuckles at the narrator’s crimes, the child laughs at both the setup and the punch line. In While You Were Napping, a devious older sister sows jealousy in her younger brother by describing a series of outlandish events involving pirates, robots, and a dinosaur skeleton that just happened to have occurred when he was taking his afternoon siesta. With scenarios that grow ever more absurd, the book is a testimony to the power of a child’s imagination as well as to the everyday cruelties of sibling rivalry.

One way to think about how picture books work is to view each as presenting the author’s particular vision of what childhood should be. This idealizing tendency results in a lot of sentimental schlock, because we all want our kids’ lives to be blissful cloud dreams populated with talking teddy bears and anthropomorphic automobiles. Offill is certainly not the first children’s author to push against this tack by celebrating more frowned-upon, yet no less crucial, ingredients to a well-rounded childhood, namely mischief and lying (Shel Silverstein and Kay Thompson, creator of the Eloise books, come to mind as forerunners), but it’s interesting to consider how the vision of childhood presented in her picture books affects an adult’s experience of her novels, all of which, including her latest, Weather, examine, in various ways, the problem of making a family in a dangerous, uncertain world.

Offill’s first book, Last Things, is the only one of her novels to be narrated from a child’s point of view. It tells the story of an eight-year-old girl, Grace, who is caught between the competing universes of her larger-than-life parents, Jonathan and Anna. Jonathan is a chemistry teacher who carries around a copy of the Constitution—the embodiment of rational, reality-based living. Anna is an ornithologist who works at a bird sanctuary, but who also believes that there’s a Bessie-like monster living in the lake near their home in Vermont. Anna likes to spin fantastical yarns in the tone of sober scientific explanations:

That night, my mother told me about the hyena men of Africa who have two faces, one in back and one in front. If a hyena man meets a young girl on the road, he shows her his first face, which is handsome and human. In back, he hides his terrible face, which has powerful teeth for crushing bones. Sometimes a girl falls in love with a hyena man, never realizing what he is. She leaves her family and marries him. Then one night the man comes home hungry and shows his true face in the dark. He takes his wife in his arms and tears her to pieces with his sharp teeth.

Since she spends most of her time with her mother, Grace feels herself drawn to the mythical side of the divide, but the narration is cleverly understated so that we never know how many of Anna’s tall tales Grace actually believes. As Anna’s behavior grows more extreme, and the reader realizes that Last Things is actually a book about mental illness, Grace defects to the patriarchal country of pure rationality by betraying her mother. Yet, even as we empathize with Grace, and pity her for the strange, disturbing situations she finds herself in, the disappearance of Anna’s perspective from Grace’s life feels consequential and tragic. The book presents a kind of thought experiment on upbringing. How do you prepare a child for the world, if you largely disapprove of what the world has become? Is the solace of intimate family life enough?

Dept of Speculation entered the world in 2014, fourteen years after the publication of Last Things (Offill’s turn to picture books came in the interim, a means, she has explained, of paying the bills). The novel applies a fragmentary, epigrammatic style to a familiar story of domestic turbulence. The protagonist, a novelist and writing teacher, and her husband, a sound artist who has a day job scoring commercials, live in Brooklyn with their daughter while suffering the financial pressures common to the overeducated, underpaid urban bourgeoisie. Offill has described the book as “a bit of a ‘fuck you’ to the way novels about domestic life are usually treated . . . I wanted to write a philosophical novel that was set in that often-trivialized realm [the family].” Indeed, one of the book’s chief charms is its ability to switch between asides on philosophy, religion, and science and descriptions of the events of the characters’ everyday lives—all without provoking whiplash or boredom in the reader. One reason this works is Offill’s liberal deployment of line breaks and white space; the slim, small novel has the feel of a book of aphorisms. More important is the book’s sparklingly dry humor. Reading it, I was reminded of the deadpan delivery of the standup comic Steven Wright.

The line breaks, the Buddhist koans, the jokes—all this results in a sense of playfulness absent from Last Things, even as Dept of Speculation grapples with many of the same problems. In the wake of the novel’s seminal event, the husband’s affair, the wife is forced to confront the question of what she wants out of family life—in essence, her own life—in a way that she has never done before:

The wife wants to go to the hospital. But she does not want to have gone to the hospital. If she goes, she might not come back. If she goes, he might use it against her. But when she is alone, the objects around her bristle with intent. This is fascinating to her but it must remain a secret. She packs her daughter’s lunches and reads her to sleep. On the playground, she impersonates a reasonable mother watching her child play in a reasonable way. She goes to work, hovers above herself as she speaks about all manner of things . . . She stays up half the night, her brain whirring and whirring. She looks up school calendars in other cities. She investigates the cost of cars, of heat, of health insurance. She makes a plan a, a plan b, a plan c and d and e. Of these, only one involves the husband.

Like Anna in Last Things, the wife in Dept of Speculation is keenly aware of the injustices and compromises that hang over her domestic situation. (A passage on how difficult it is for a woman to live the life of an “art monster” informs Claire Dederer’s excellent Paris Review essay on the work of Woody Allen and other “monstrous men”). Unlike Anna, though, the wife is mentally stable, and she’s able to find a way to continue within the family unit. In the final pages of Dept of Speculation, the textual intrusions from philosophy, science, and religion all but fall away; it’s as if all of the wife’s desperate attempts to find meaning, manifested in the noise of secondary sources and spiritual anecdotes, have finally ceased. The book ends on a note of tentative hope.

Weather presents itself as a successor to Dept of Speculation in style and themes even if it is not an outright sequel. Again we have a family of three, living modestly in New York City. This time the wife and narrator, Lizzie, is a librarian at a local university, and her husband, Ben, is a classics PhD who has taken up writing code for video games. Their son, Eli, is in first grade. The morsels from science, philosophy, and religion appear as well, although not as frequently. The differences between the two novels quickly begin to reveal themselves. At one point in Dept of Speculation, the narrator muses that “the reason to have a home is to keep certain people in and everyone else out.” In Weather, the walls have come crashing down, and the world has intruded upon the domestic sanctum. Where the earlier book keeps the focus on its unnamed central characters, as if to maintain a sense of allegory, Weather is populated by a Dickensian abundance of minor figures: Mohan, the guy who works at the local bodega; Mrs. Kovinski, a nosy neighbor in their building; Tracy, a bartender and Lizzie’s friend; Sylvia, Lizzie’s grad-school mentor—the list goes on. In its early pages, the book reads like a kind of fragmentary diary of a neighborhood, enlivened by Lizzie’s nimble observations and searching empathy. The plot, which arrived like a gun blast in Dept of Speculation with the revelation of the husband’s affair, emerges more slowly. In addition to serving as a sounding board for library patrons and neighbors (“I wish you were a real shrink,” Ben tells her. “Then we’d be rich.”), Lizzie acts as a kind of guardian for her brother, Henry, a recovering addict and continuing source of worry for her. She attends to him often; they go on walks in which they contemplate such subjects as whether Henry has sold his soul to the devil:

“What if I sold my soul to the devil when I was a kid?”

“You didn’t sell your soul to the devil.”

“What if I did but I don’t remember it?”

“You didn’t sell your soul to the devil.”

“But what if I did?”

“Okay, but think, Henry, what did you get for it?”

Offill peppered Dept of Speculation with references to poets like Rilke and Ashbery, and so I have to wonder whether Henry, with his dark thoughts and pathological helplessness, represents a nod to the protagonist of John Berryman’s Dream Songs (“bitter Henry, full of the death of love, / Cawdor-uneasy, disambitious, mourning / the whole implausible necessary thing”). An important bit of background, revealed late in the novel, is that Lizzie left her PhD program to take care of Henry during one of his vulnerable periods. With help from Sylvia, she later landed the gig at the university library. Lizzie’s constant minding of Henry is another source of tension in her marriage.

Sylvia is a frequent public speaker and host of Hell or High Water, a popular podcast about environmental and social catastrophe—imagine a cheerfully busy public intellectual in the vein of Steven Pinker or Martha Nussbaum. She asks Lizzie to be her part-time factotum, serving as her assistant on the road and answering listener emails. Often focused on imagined scenarios resulting from climate change, the questions and Lizzie’s answers are woven into the text of the novel and help fuel Lizzie’s increasing survivalist paranoia. Roving the aisles of the library during her lunch breaks, she picks up tips on things like how to make a candle from a can of tuna and compiles a list of prepper acronyms:

GOOD = Get Out of Dodge

DTA = Don’t Trust Anyone

FUD = Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt

BSTS = Better Safe Than Sorry

WROL = Without Rule of Law

YOYO = You’re on Your Own

INCH = I’m Never Coming Home

For a book that begins with not a lot of action, Weather soon becomes crowded with incident. In addition to the travails with Sylvia, there are happenings related to Eli’s school, the driver of the car service Lizzie uses although she cannot really afford it, the meditation classes given in the basement of the library. When Henry’s wife becomes pregnant, Lizzie worries that fatherhood will upset the delicate balance of his life and threaten his sobriety. She and Ben continue to be at odds. And then Donald Trump is elected president.

It now seems inevitable that every American novel set after 2016—perhaps whether it describes current events or not—will face the question of how it addresses the “new normal” of living in a society faced with existential threats of creeping authoritarianism, state-supported bigotry, and flagrant public corruption, not to mention the coming global climate disaster. (As Will, Lizzie’s war-correspondent almost-paramour, tells her, “Your people have finally fallen into history . . . The rest of us are already here.”) In Weather, Trump’s election represents not so much a break from the status quo as an accelerant for everything the characters were already afraid of. In the second half of the book, Lizzie’s personal life unravels alongside the nation’s sense of normalcy. Ben takes Eli on a three-week road trip that threatens to become a more permanent separation; Lizzie flirts with a neighbor and tiptoes toward the line of having an affair; Henry relapses, beset by morbid visions of causing his infant daughter’s death. In its final pages, the book is harrowing, gorgeous, and tender. As in Dept of Speculation, the novel’s conclusion sees the main character grasping for hope but under completely different circumstances and for completely different reasons. Where the wife in Dept of Speculation looks inward and to her immediate family for solace, Lizzie is forced to find it in her friends, coworkers, and neighbors. If one agrees that a well-crafted novel can have a lesson, however implicit, there is one here—namely, about what sort of community it will take to overcome our present and future obstacles.

One of the best things about reading a book to your child is that it’s impossible to check Twitter while you’re doing it. Nothing scary can happen during that time; the world is at bay, however temporarily. In Jenny Offill’s picture books, childhood occurs as a carefree frolic within a protected world. Actions have consequences, but those consequences are contained and limited by the boundaries of the family. Her picture books remind us of what is special about being a kid, the innate sense of trust and creativity that allows someone to do something like walk backwards all the way home or imagine eating a meal of French-fry sandwiches alongside a giant, friendly robot. But in recent years, the United States government has shown that once-sacred family bonds can be broken in service of nativist immigration policy. Climate change has fundamentally altered the way we think and talk about the future our children stand to inherit. (“Do you really think you can protect them? In 2047?” Sylvia asks Lizzie in Weather.) And now, as I complete this review, daily life around the world has ground to a halt in response to a rapacious pandemic for which we seem woefully unprepared. Even before the present crisis, I had often found myself wondering, when sitting down to read a book about crayons or mallard ducks in search of a place to build their nest, whether we’re doing our children any favors by inculcating a sense of the world as a just, fair place when so often it seems that the opposite is true. Henry is the extreme embodiment of this darker view. He is debilitated by fears of what the world will do to his child. “Do you ever think it’s weird that we even have families?” he says to Lizzie at one point in the novel. But while Weather doesn’t explicitly disavow Henry’s point of view, it doesn’t condone it either. There is such a thing as a healthy amount of fear: anyone who isn’t scared by the facts of climate change, for example, shouldn’t be trusted. But you shouldn’t live your life according to fear, and you certainly shouldn’t raise your children in an atmosphere of fear. Weather shows how the family can never be a fully protected or separate unit, anyway, but is more like a porous skin through which we interact with others, form relationships, let outsiders in. And now, during these lonely, seemingly endless days of shelter in place, the book is a reminder of all we have to gain from the other lives in our local orbit. ![]()

Wilson McBee is a staff writer for SwR.