The Noise an Object Makes

Reviews

By Elizabeth Gonzalez James

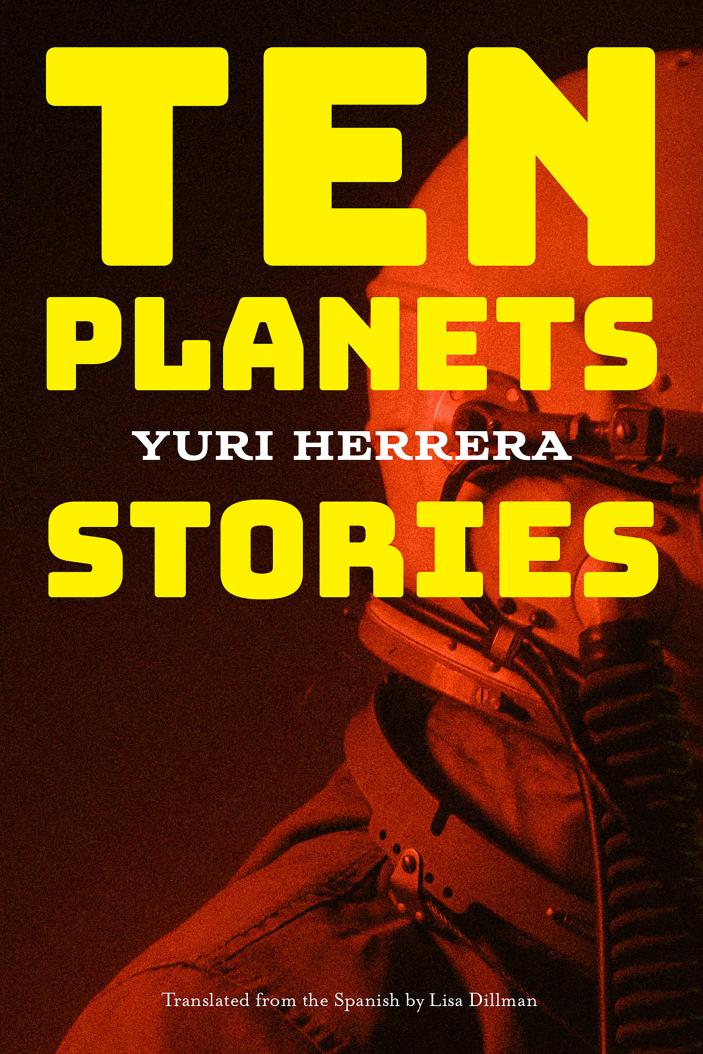

A mother follows GPS through empty streets, vainly searching for her daughter. A man can’t escape the tyranny of his corporate overlords, even in his dreams. A bailiff tasked with collecting art made by abused monsters wishes he could suffer for creation too. These are some of the subjects of Yuri Herrera’s latest story collection, Ten Planets, newly translated from Spanish by Lisa Dillman and published this month by Graywolf Press. Herrera’s characters are disconnected and dislocated, beings existing without a homeland and frequently without others as they try to make sense of what meaning a life lived alone might hold. Each story seems to comment on the insularity of modern life and posit what that insularity could turn into if taken to its logical end.

In “The Obituarist,” the protagonist’s job is to eulogize the recently deceased by taking inventory of the things they’ve left behind—a vital task once we learn that people in this plausible near-future spend their entire lives cocooned inside buffers that render them publicly invisible. These shells effectively reduce people to their function (delivery person, plumber) and meager possessions. An interesting escalation of the way people live now, walled behind a screen name and an avatar, the story asks whether our visibility to others is the source of history and perhaps even existence. One could imagine Herrera asking us to turn Descartes’ cogito, ergo sum on its head: “I reflect, therefore I am.”

Human life perverted by technology is one of Herrera’s recurring themes. In “House Taken Over,” a smart house punishes a family for having phony intentions; in “The Objects” (one of two stories in the collection bearing this title), a mother follows dots on a device called a Miniminder as she tries to catch up with her daughter and husband. It’s an eerie scene: a woman alone at night running, seeking her family but chasing only blinking dots that recede further and further. The dot, a poor representation of a living being, also represents the unknowableness of other people when mediated through a screen (and perhaps just in general), especially when closeness seems so tantalizingly achievable. A dot is not a person any more than a screen name is, yet how often do we conflate the digital presentation and the person?

Herrera is also very concerned with how our roles in life can become terrifyingly inescapable. In the second story entitled “The Objects,” people spend all night in a sort of lucid dream state where they become animals according to their social status. Corporate bigwigs transform into sharks and lions while the story’s protagonists, who spend all day laboring for their bosses, live all night as a rat and a louse, unable to escape the bonds of their employment and caste even in their imaginations. In “The Monsters’ Art,” hairy creatures are kept chained underground and forced to create music and art, presumably for consumption by people living above them. In one scene, a bailiff beats the creatures without mercy while stealing their precious works. The monsters are allowed no life beyond their utility as creating machines—a not-too-subtle metaphor for the creative process and a nod to Karl Marx’s theory of alienation. A person separated from the full life cycle of their labors, a person limited to being one cog in a churning machine, is deprived of their ability to direct their fate. They may as well, Herrera seems to say, be imprisoned in a dungeon.

Ten Planets also invites readers to trace the parallels between Herrera’s work and that of other postmodern fabulists. Like Jorge Luis Borges, Herrera is concerned with the uncanny, the strange, and the outsized impact Cervantes has had on modern writers. Dragons appear at the edge of a flat earth to swallow unwitting sailors, only to reappear several stories later as disheveled explorers mistaken for monsters. Dragon, in this case, becomes a name applied to anything frightening and unidentifiable, inflated like Quixote’s windmills into terrifying proportions. Quixote himself appears in a short story written by an alien named Zorg, who offers this beautiful quip: “A character is nothing but the noise an object makes when it’s touched.” Are Quixote, Zorg, and the dragons merely objects arranged and poked? Is the author (Herrera) simply the person recording their reactions? It’s certainly an arresting image.

Herrera’s collection is also reminiscent of Italo Calvino’s classic Invisible Cities, wherein the explorer Marco Polo attempts to explain to the emperor Kublai Khan all the fantastical cities he has encountered in his travels. He describes cities suspended among trees, cities that are labyrinths, each fanciful vignette building to the realization that Polo has been describing his beloved Venice all along. The ten planets of Herrera’s title could also exist in this way, each bizarre world shining a mirror on our own. In “Living Muscle,” a planet of tissue and muscle beats alone, suspended in the cosmos, simultaneously vulnerable and powerful. When explorers attempt to probe it and learn its secrets, the planet vibrates so intensely that it destroys their probes. And when the explorers decide to discontinue their mission and leave the planet alone, the reader cannot help but be touched and thrilled at this profound act of mercy inside what is otherwise a vast and uncaring universe.

Throughout the twenty stories that make up this slim volume, Herrera invokes aliens and monsters throughout space and time, in galaxies near and far. Like Marco Polo, the author brings back his findings to us, asking that we listen with ears wide open and accept the prospect of worlds beyond our reckoning. Herrera writes to this climax, then beyond: to the chill of familiarity that passes over us when we realize that the one telling these tales has never left the Earth.

Elizabeth Gonzalez James is the author of the novels Mona at Sea (SFWP, 2021) and The Bullet Swallower (Simon & Schuster, 2024), as well as the chapbook, Five Conversations About Peter Sellers (Texas Review Press, 2023).

More Reviews