Naked Wives and Surprising Penises

Reviews

By Kyle Beachy

Maybe it’s unconventional to start with the back matter, but let’s. After paging through roughly 500 photographs taken by Ed Templeton between 1995 and 2012, after reading or not reading the many excerpts from Templeton’s tour diaries that give context to these photos, the reader of Wires Crossed comes across the most unromantic description of skateboarding possible. It comes from an interview with Templeton aimed to provide the non-skating artbook crowd with a few basic inroads to the book’s project. (That project is inseparable from the culture, activities, and business of skateboarding; speaking with Johan Kugelberg, Templeton said, “I needed to not alienate the art world by being too ‘insider.’”)

Essentially, Toy Machine is a marketing company. Because for the most part all skateboards are exactly the same. They’re all seven-ply rock Canadian maple decks with different marketing applied to them. What makes Toy Machine different is our style, graphics, team, and brand identity.

This essential insanity plays out across t-shirts and trucks and grip tape, too, but its locus is the board. The board company is the brand with whom a pro skateboarder is most associated; name a pro skater and I’ll either name their board sponsor or buy you dinner. That remains true even as board brand paychecks have shriveled next to footwear sponsors—and even as the boards themselves have diminished from individually screenprinted art objects to the heat-transferred ad spaces of today.

Given the extremely slim profit margins and lurking threats from unbranded and much cheaper blank skateboards, that there’s even a skateboard industry at all in 2023 is due largely to the success it’s had turning commercial choices into existential ones. Depending on where you live, you can go to a skate park today and find Quasi people and Frog people, Fucking Awesome and DGK and, I suppose, Primitive people, though I’ve never met one myself. From this first-order brand identification follows all nature of clothing and footwear and accessory choices, along with subtler tells like trick selection, down to their very posture.

Even today, in our era of great flattenings, you can spot Toy Machine people. They either have a lot of hair or a shaved head. They skate handrails. They wear work pants and vulcanized shoes and colorful socks. You’ll run into people with prominent Toy Machine tattoos based on a logo that Ed Templeton doodled thirty years ago. This is even more impressive when you consider that no other heritage board brand, perhaps no other skateboard brand at all, has weathered as many or as massive the exoduses as Toy Machine has. As Jason Dill once told Patrick O’Dell, “It was almost like Toy Machine . . . gave birth to other Toy Machine skateboarders, as a way to refill the team.”

This is the particle-accelerated branding landscape out of which Ed Templeton, painter and photographer, emerged. By now, we’ve grown accustomed to artists who, through the aesthetic charm and conceptual simplicity of their work, become brands. Templeton is something of this pattern’s inverse—he’s the brand whose work gradually and determinedly found a foothold in the art world while never shedding the aesthetic and conceptual hallmarks of that brand. Which brand, since 1993, has been called Toy Machine: “I do the graphics, and set the tone, language, and ethos for the company.”

What is that tone, language, and ethos? Suburban California destitution. Bold, primary colors and spiritual malaise—devils with horns and zoinked-out turtle kids. Cigarettes. Naked wives and surprising penises. A distrust of easy happiness and a deep, broader distrust of marketing deployed for the sake of Toy Machine marketing. Contradiction and irony. Fractured bones and broken homes; absent fathers, absent fathers, absent fathers.

“I’m not the most talented artist,” says Templeton in Mike Mills’ 2000 film, Deformer. “I work at it, and try to be consistent with what I do.”

The result is an artist whose work is almost unbearably already known. His website lists twenty-six published books of street photography and paintings, many of which have accompanied solo gallery shows. Wires Crossed is the first of these books to center the subculture of skateboarding explicitly. Templeton describes it as containing “essentially my life’s work,” making it a kind of swan song to his time as a professional skater. The core of this work is what Templeton calls “the enigma of what makes a person a skateboarder.”

As a skateboarder myself, I did not require a large format, clothbound book of 500 photographs to understand Templeton’s project. In fact, I did not even particularly want the book when it showed up at my door. And yet I was moved after my first read and chose to keep it close by. And I have been moved each new time I’ve opened it and waded back into the broad ocean of Templeton’s work.

But moved by what, exactly? Something more interesting than nostalgia. We might ask whether the photos are any good. I am not so sure, though nor am I sure this question is all that useful for the professional-skater-turned-artist. Do these individual compositions and their curatorial arrangement on these pages catalyze new ways of seeing and experiencing a familiar world? Well, yes, but that’s due less to Templeton’s technique than to the ways skateboarding encourages and facilitates oblique ways of looking, doing, and finding meaning. These seventeen years’ worth of photographs are framed as a kind of endless road trip, partially through Europe but mostly along highways through Albuquerque, Tulsa, Davenport, and so on. By one count, barely twenty of the photos from Wires Crossed capture the activity of skateboarding. By another, they all do—the sitting, swimming, shooting, singing, driving, and a hundred other doings contained within that broad, enigmatic gerund.

The best photos are those that tell us something not only about the subject but also about the way the subject is seen. To have an eye for the banal is to have a certain faith in the banal, a sense that there’s something worth looking at inside the mundane. To re-present the banal as art is to make a claim, one that’s not always welcome. Why, exactly, must I be subjected to this banality? Because there’s energy lurking inside even the most routine human scene, some tiny, hidden tension, or potential. The basic tactic of Templeton’s argument has always been repetition. For example, not just a few pictures of teenagers smoking, but two full books. His gaze is both searching and certain because Templeton—we might as well say it—is a believer.

I’m not always in agreement with what Templeton believes is a compelling photo. There’s a fundamental ostentation to his faith-based approach, a Look, Look Here!-ness that succeeds much more on the cumulative than individual level. In Wires Crossed, this accumulation is furthered by written texts that serve as captions and echo the images’ semi-documentary approach. “Because Arizona doesn’t do daylight savings time we were early to the shop so we skated a nearby college,” starts one entry. These plots do not escalate, nor do any of these stories quite end. “Ate a veggie pocket I got at a health food store this morning while everyone ate at I-Hop. Got some rooms at Travelodge they suck & it’s hot. Talked with Elissa & went to bed.” They’re wonderfully unvarnished accounts of hangovers and autographed breasts and cops and fireworks and inflatable boats. The events stack and merge into a kind of wall of happenings, none interesting enough to distract from the larger, holistic project Templeton has undertaken.

Which project is further served by the book’s brilliant merger of chronology and total timelessness. As we dutifully advance through annual trips across America, each section seeming to announce itself with an illustrated map of our route, the photographs within each of these presumed sections adhere to no obvious organization, least of all a timeline. This nonlinearity undermines any narrative meaning we might hope to find. Instead, the book turns away from linear time and chases after several other frameworks, space and embodiment among them.

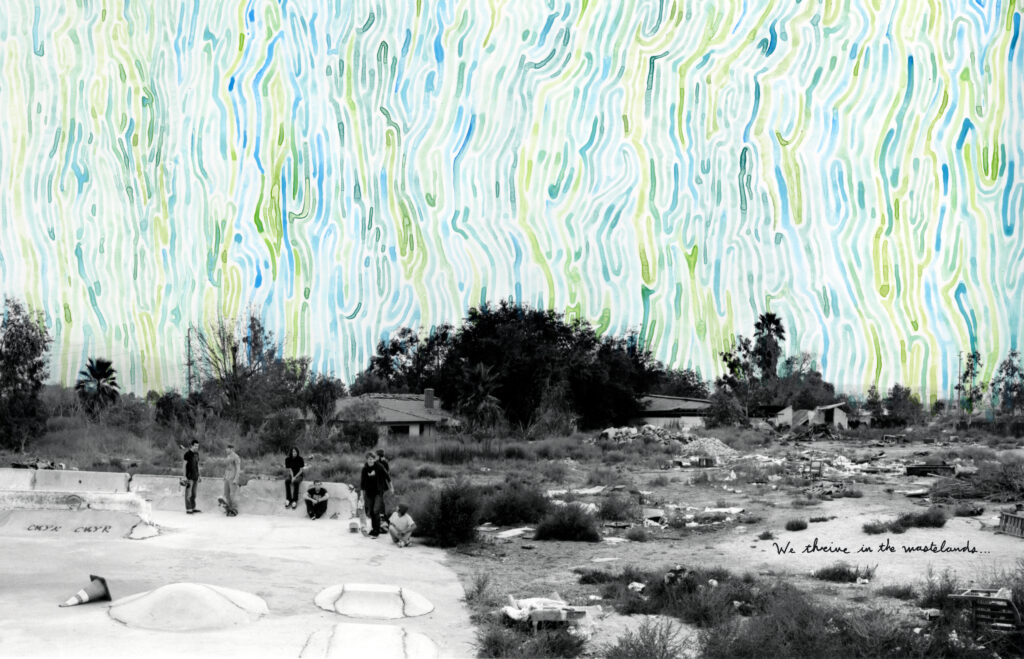

The early pages of Wires Crossed function to shape the world via a hundred pointillist jabs—here are young people in hotels and vans and sleeping bags, traveling as units while insisting on their individuality. Like Nan Goldin’s subjects, these skaters are a kind of chosen family. They are also, technically, Templeton’s employees, sitting with dice and beers, sweating in the heat. There’s destruction and friendship, bathroom haircuts and bridges to jump off of. And from this world, contours emerge to establish themes. A sequence of photos featuring police and security gives way to photos centering sex, which give way to drugs and alcohol and eventuate in a haunting series that documents wounds, concussions, and concern. The book concludes with a turn to the hinterlands, or wastelands, closing with an apparent nod to the emptiness at the heart of Templeton’s enigma: its ongoing-ness and basic inscrutability.

![]() A career that began with emulations of Larry Clark and Egon Schiele has come, it would seem, full circle. Skateboarding has always been marketing. The art of desire, then—the enigma of what could possibly compel a young person to drive hours through cornfields to catch a glimpse of pro skaters in Davenport, Iowa. And to shape their identities around this particular skateboard brand over all other brands. Maybe, suggests Wires Crossed, it could be anyone. Maybe it’s just that Toy Machine was the company willing to show up in Davenport. Maybe it’s a matter of being there and indulging the romance, even as you know well the romance’s limitations and contradictions. Maybe making art is as simple as being honest about desire. Maybe that’s what’s got me so moved.

A career that began with emulations of Larry Clark and Egon Schiele has come, it would seem, full circle. Skateboarding has always been marketing. The art of desire, then—the enigma of what could possibly compel a young person to drive hours through cornfields to catch a glimpse of pro skaters in Davenport, Iowa. And to shape their identities around this particular skateboard brand over all other brands. Maybe, suggests Wires Crossed, it could be anyone. Maybe it’s just that Toy Machine was the company willing to show up in Davenport. Maybe it’s a matter of being there and indulging the romance, even as you know well the romance’s limitations and contradictions. Maybe making art is as simple as being honest about desire. Maybe that’s what’s got me so moved.

Kyle Beachy is the author of The Most Fun Thing: Dispatches From a Skateboard Life, one of NPR’s best books of 2021, and a novel, The Slide.

More Reviews