Natural Ecstasy

Reviews

By Mila Jaroniec

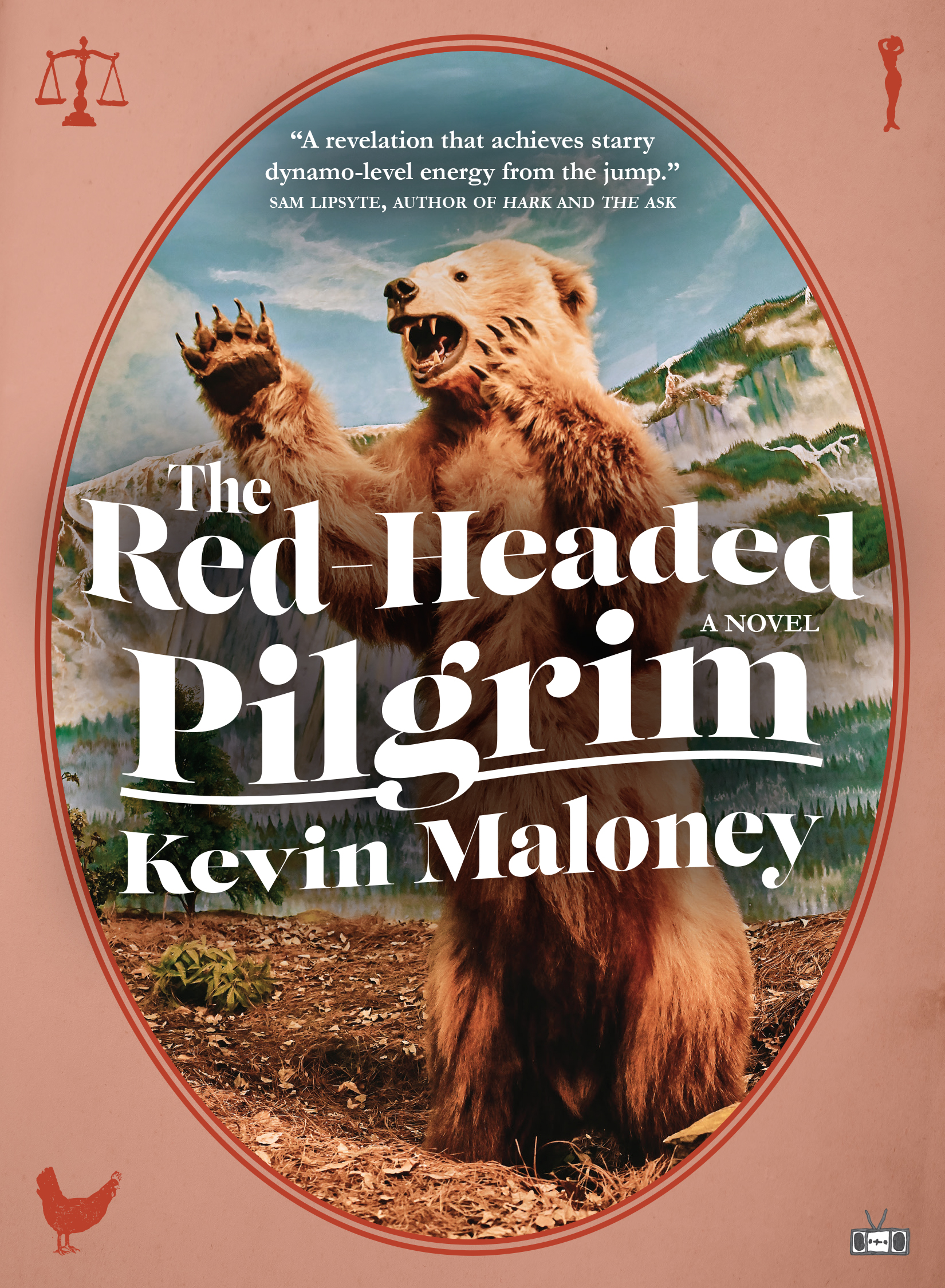

The Red-Headed Pilgrim (Two Dollar Radio, January 2023) by Kevin Maloney is exactly the type of novel with which to begin a new year: wild, heart-expanding, and almost painfully funny, here to reset our sense of freedom and possibility as we once again stare down death from page one of the Gregorian calendar.

The Red-Headed Pilgrim begins with fictional forty-two-year-old Kevin Maloney sitting outside in an office park, watching the trees sway in the wind and having what might be called a midlife crisis. He is simply not where he thought he would be at this point in life.

Like me, Kevin Maloney also tries to write at work when possible. I have just spent my morning scheduling paid posts on the company’s social media accounts and covertly working on this review. Both of us are worried about having to spend the rest of our lives in a depressing office, trying to write books that enough people will want to buy so we don’t have to work in depressing offices anymore. Given this, it’s clear that The Red-Headed Pilgrim will resonate with a wide audience. If there’s one thing we all have in common, it’s the certainty of an existential meltdown.

The fictional Kevin Maloney’s spiritual pilgrimage begins in high school after he suffers a psychotic break on the football field and runs into the forest. There, the tree branches look to him like dendrites stretching up into the great universal consciousness. For the first time, he becomes intimately acquainted with the singularity of life and the inevitability of death. After he eventually gets himself together and goes home, his parents send him to a therapist. Instead of prescribing him some sort of mood stabilizer (a big indicator that the setting is not the hyper-medicated present day), the therapist suggests that Kevin is on a spiritual journey.

This diagnosis is more than just validating—it gives Kevin a project.

Back at school, Kevin forms the Inevitable Death Brigade with a handful of like-minded morbid teenagers and meets a girl he likes, but then decides to kill himself when she makes out with his best friend. Before the attempted suicide, he writes a poem so good he forgets to kill himself.

Writing, he discovers, is the way out and the way in.

After he forgets to commit suicide, Kevin shows his poems to his English teacher, who congratulates him on his self-awareness and introduces him to Brautigan and Burroughs and Hesse, other writers who have faced the void. Something like a portal opens up. Others have felt the hugeness of existence and the lavender mist of death on the horizon. Others have responded to time with their own versions of the riddle. There is an immediacy to it, this need to experience the whole of life the way it was meant to be experienced—insatiably, radically, with a handle on the pulse of its absurd and consuming beauty.

Over in Death Claims, my coworker answers the phone: “Are you calling to report a death?” Every day, there it is: death, the final punctuation mark. Some days it helps me feel grounded; other days, it’s panic-inducing. When I start to buckle under the weight of small agonies, I remind myself that none of it is forever. No matter how stagnant things feel, there’s always a choice.

When Kevin feels the world closing in, he picks up and moves across the country, not once but a few times. Guided by the spirits of Ginsberg, Kerouac, Walt Whitman—and possibly John Wayne—he undertakes an ongoing mission to search for god, work as little as possible, read as much as possible, lose his virginity, and do his best not to get frightened out of his natural ecstasy. But then, about halfway in, his girlfriend gets pregnant and the second part of his spiritual awakening commences.

Like Kevin Maloney, who found himself a young parent in a precarious situation, I grew up before I was ready. When my son was born, it suddenly became important to have a steady paycheck, a home in a decent school district, a savings account. In other words, everything Kevin initially eschews to avoid becoming like his father: working a 9-5, driving back and forth to and from work, caring about insurance, all the trappings of adult life we’ve been taught to fear by the infamous Trainspotting poster hanging in every high school stoner’s bedroom.

But it’s not that reaching for anything more than what capitalism wants us to want is inherently stupid and leads to spiritual failure and a soft-bellied retirement. It’s that worldly responsibilities, as stifling as they can feel in the moment, anchor the journey. The point of the spiritual journey is not to transcend this realm so fully that we disconnect. It’s to get closer: to ourselves, to each other, to what makes us human. The trick is not to sacrifice all meaningful love and connection for the sake of burning for the ancient heavenly dynamo in the machinery of night. It’s to figure out how to keep stoking those fires and still pick up the kids from school on time. Beyond that, it’s to give the kids a safe and happy home base where you can transmit that insatiable hunger for wonder and transcendence. To avoid becoming one of those stuck, depressed adults that horrify children by showing them what enough time on earth can do to the unprepared.

It’s hard to write an honest book. It’s even harder to write an honest book that is charming, hilarious and doesn’t make the author sound like a crusty, tower-dwelling sage. If the character Kevin Maloney were a Tarot card, he would be The Fool, card zero, the starry-eyed hero on the first step of his beautiful, terrifying journey, the whole of life unspooling before him in an endless cosmic thread. Cross Tom Robbins with Richard Brautigan with Evelyn Waugh, add a touch of Umberto Eco, and you have the writer Kevin Maloney, one of the last remaining holy fools willing to undergo a soul’s journey and write about it, honestly and ecstatically, with no moralistic lesson save one: the lesson is the journey, and we don’t have a lot of time. It’s worth it.

Mila Jaroniec is the author of two novels, including Plastic Vodka Bottle Sleepover (Split Lip Press). Her work has appeared in Playgirl, Playboy, Joyland, Ninth Letter, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, PANK, Hobart, The Millions, NYLON and Teen Vogue, among others. She earned her MFA from The New School and teaches writing at Catapult.

More Reviews