Of Monsters and Women

Reviews

By Jude Burke-Lewis

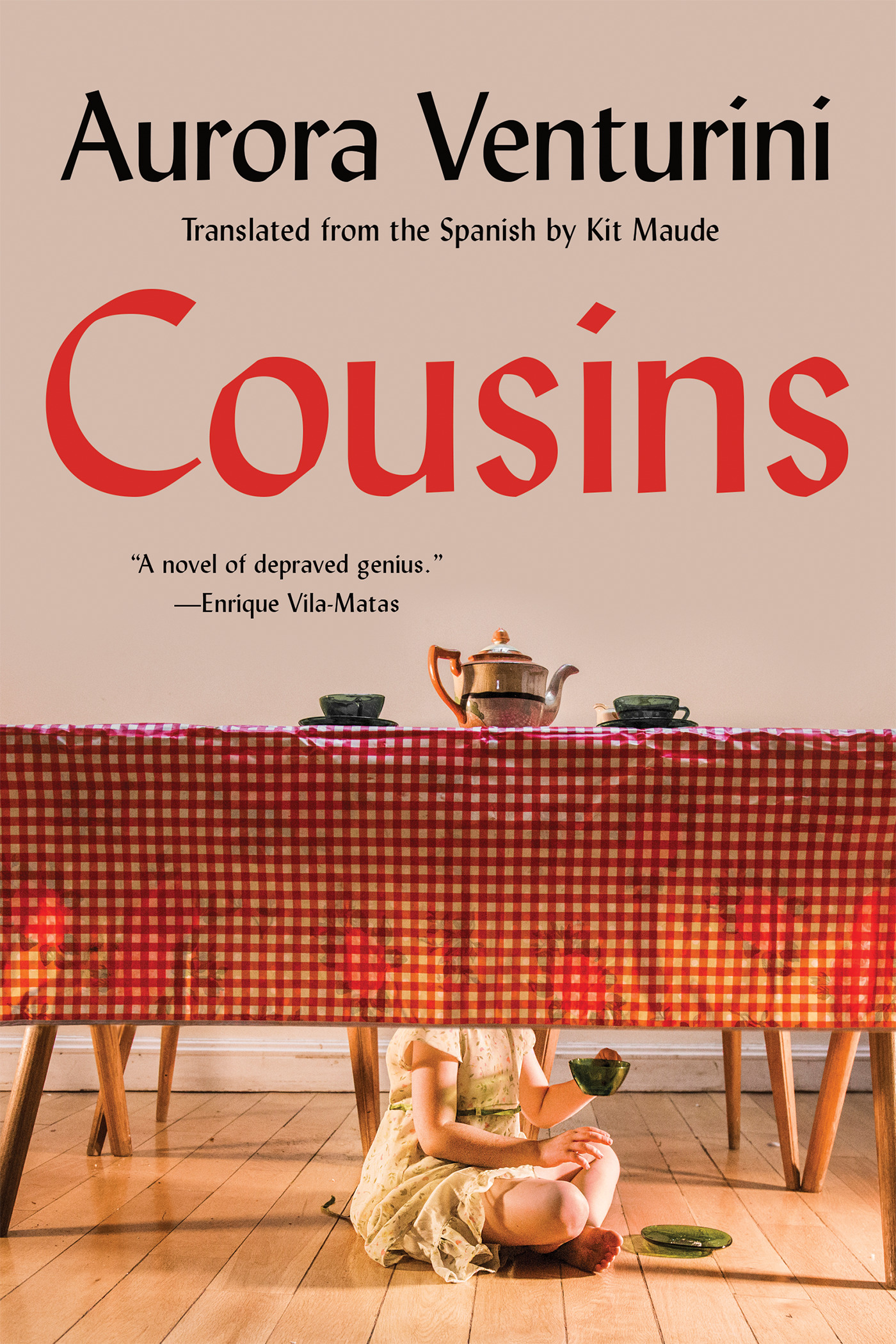

“We were unusual which is to say that we weren’t normal.” This is how the narrator of Aurora Venturini’s extraordinary novel Cousins describes her family in its opening pages. The same could be said of the work itself. Darkly funny, grotesque, often disturbing, and infused with antipathy, misogyny, casual violence, and political incorrectness, Cousins is also a brilliant coming-of-age story that turned its eighty-five-year-old author into a literary star in her native Argentina. First published in 2007, it’s now available for the first time in English thanks to a masterful translation by Kit Maude.

In interviews at the time of the novel’s publication, Venturini described Cousins as autobiographical, saying that her own family was “very freakish.” Information about Venturini is sparse (in English at least), but like the narrator, she grew up in La Plata, Argentina. She was born there in 1922 and died there in 2015. In between, Venturini spent several years living in Buenos Aires. She was close friends with Eva Peron and met Jorge Luis Borges, who presented her with an award for an early work. After the fall of the Peronista government, she moved to Paris, where she befriended many influential thinkers and writers, including Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Albert Camus. In a career that spanned over sixty years, she published more than forty works as a novelist, short story writer, poet, and translator. But none has made quite the same impact as Cousins.

Set in the 1940s in La Plata, Cousins is told from the perspective of Yuna Riglos, a young woman and gifted painter. Although she struggles with reading, writing, and speaking, she also has no filter. Nothing is off-topic for Yuna: not bodily functions, not sex, nor anything else that might be considered taboo. Her narration lurches wildly from subject to subject, reflecting both her unique viewpoint and the peculiar situation in which she grows up.

The women in Yuna’s family are nearly all as broken as she is: each of them “was missing something or had some other failing.” Yuna’s younger sister, Betina, is severely disabled: incontinent, almost non-verbal, and requires the use of a wheelchair. Yuna describes her as a “mistake of nature.” An aunt, Nené, has a breakdown following her mother’s death, with macabre consequences. And then there are two “imbecilic younger cousins.” Carina has extra toes, becomes pregnant at fifteen, and dies after a backstreet abortion. Petra, a dwarf, starts having sex at the age of twelve and practices “the oldest profession.” She is also Yuna’s closest ally.

This is not a loving or nurturing family. Yuna’s mother, a school teacher, regularly metes out discipline to her daughters using a pointer, while her aunt Nené calls both Yuna and Carina “retarded.” Yuna is merciless in return. She taunts Nené, at one point stealing her false teeth and flushing them down the toilet. And while she laments that her mother is “burdened with both abandonment and freaks,” she admits, “I never felt sorry for her because I didn’t love her.” Neither woman is supportive of Yuna’s art. Her mother even dismisses it as a “childish phase” that she’ll soon get over.

The only character who does encourage Yuna to keep painting is her professor, José Camaleón. He gives her private lessons after she completes her diploma at the School of Fine Art, buys her paints, and arranges her first exhibition. When she becomes successful, he appoints himself her representative. But he is as much a predator as he is a benefactor, a fact which is obvious to the reader if not to Yuna herself. Early in the novel, when Yuna is just fourteen, he kisses her, telling her that she is “very pretty” and that when she grows up, “we’d court and he’d teach me things just as nice as drawing and painting.” Just how much of a monster he is only becomes apparent as the novel progresses.

But Camaleón is far from the only predatory man in Cousins: almost everyone in the book is affected by violence and cruelty, particularly of a sexual nature. Carina’s pregnancy results from her being raped by an older married neighbor whom Yuna calls “the potato man.” And although Petra uses sex as a weapon—in fact, she uses it to exact a fitting revenge for her sister’s death—she is also its victim. Watching Petra bathe, Yuna remarks on the “bruises darkening the skin of her sorry little body and one or two bite marks and scratches or something similar” that her clients have dealt her.

Yuna is driven to improve herself, to “triumph over all that awful excrement and deformity” that she grew up alongside. Her art allows her to do this. Throughout the novel it has been her only true means of self-expression. She pours all the “feelings doubts and strange speculations regarding life, destiny and death” that she can’t express in words into her paintings. These works become her ticket away from her upbringing, and by the end of the novel they are “wanted by important galleries and exhibition venues.” But success comes at a cost, and the reader is left wondering whether it has been worth it: “An enormous melancholy flooded into my paintings and it made them worth more because people find consolation in seeing their sorrows.”

Despite all this violence and trauma, reading Cousins can be a mind-bending and, occasionally, laugh-out-loud experience. This is largely due to Yuna’s distinctive voice. Disarming in their directness, her freewheeling thoughts gush forth onto the page without structure or much standard punctuation. Commas and periods cause her head to go “buzzbuzzbuzz.” Vulgar references—“my meals were, you might say, accompanied by the perfume of my sister’s poo and showers of piss”—sit alongside commentary on Yuna’s efforts to improve her speech and vocabulary, the nature of existence, death, art, and family, often in the same sentence. This disjointedness can sometimes be both dizzying and disconcerting. In one of the novel’s later scenes, Petra begins to complain about Betina’s medical treatment. Yuna stops her “because we’d already had too many funerals and there was no doubt that the thing floating in the laboratory jar was worthy of being on our heraldic crest and look at the impressive vocabulary I’ve mastered thanks to the dictionary.”

Such literary inventiveness and experimentation helped Cousins win the New Novel Award from Página/12, one of Argentina’s most popular newspapers, in 2007. In her introduction, Argentine author and one of the contest’s pre-jurors, Mariana Enriquez, writes of her surprise, confusion, and admiration on first reading the novel: “If the jury recognized how radical the text and story were, it would have a good chance of winning.” Good thing they did.

Jude Burke-Lewis is originally from the UK and now lives in Oxford, Mississippi, with her husband and two cats.

More Reviews