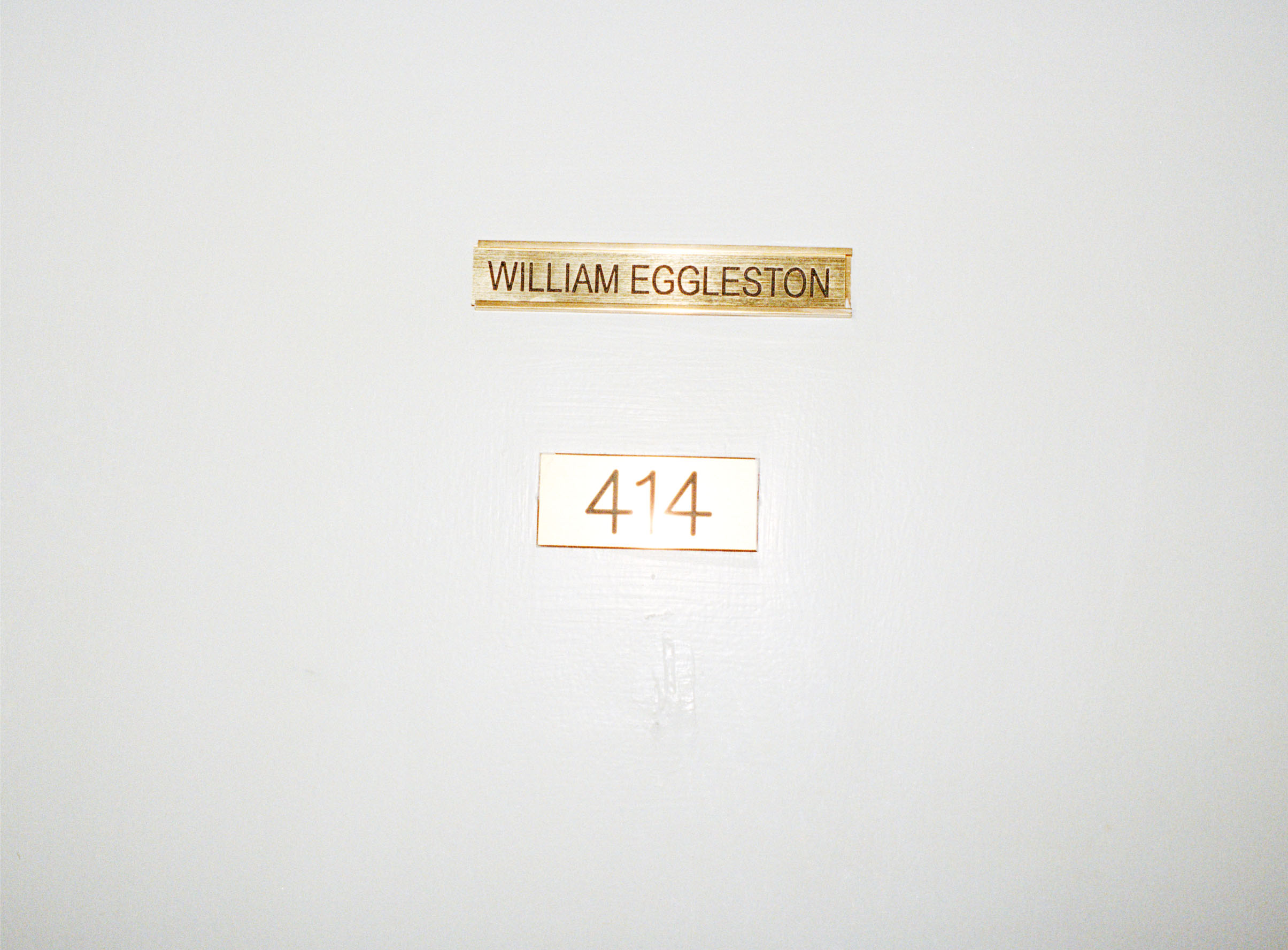

On the Road to Nowhere | William Eggleston 414

Reviews

By Michael Bible

There’s a scene in a documentary I saw recently about Italian truffle hunters. A young truffle broker is begging a famous hunter in his late 80s to divulge his best hunting spots. Truffles—the rare, prized mushrooms—go for hundreds, sometimes thousands of dollars a pound, and once the elder hunter dies, no one will be able to find the huge truffles year after year. But the old man declines. I’ll never show you my secret spots, he says, but I will take you hunting. There’s something in the old hunter’s indignation. After all, he’d spent decades honing his search only to have this rich young man begging him to hand over his secrets for free. I realized that what the old man was trying to tell the younger man was there was only the constant search. Good conditions. A smart dog. Lots of luck. There were no shortcuts.

This is the spirit of the new visual memoir William Eggleston 414, published by Steidl. The premise is simple. A road trip with William Eggleston. Eggleston is the master of hunting out the beauty in the ordinary. His bold color photos have influenced generations, and he is easily the greatest living Southern artist. Eggleston takes the filmmaker Harmony Korine and the photographer Juergen Teller on a ride through the Mississippi Delta. While something like this could come off as fawning, in the hands of Teller and Korine it becomes a remarkable artistic travelogue. A car. A driver (in this case Eggleston’s son Winston). Some cameras. Some color film. And no destination. In the short forward Teller recounts asking, “Where the fuck are you taking us?”

“I wanted to show you nothing,” Eggleston says.

What follows are 100 or so images that trace their journey through a profoundly forgotten America. Teller and Korine manage to pay homage to Eggleston’s style without trying to ape the master. Anyway, Korine and Teller aren’t amateurs. Their photos lovingly capture a man they’ve no doubt long admired. Korine’s provocative movies might not seem to relate to Eggleston’s crisp color images, but films like Trash Humpers could not have existed without Eggleston’s experiment in cinema, Stranded in Canton. Eggleston’s influence on Teller is perhaps more obvious. Teller’s famous oversaturated snapshots of high fashion run counter to the highly produced images his field is known for. But Eggleston long ago declared that he never took a picture of the same thing twice, and Teller has followed suit. Eggleston and Teller aren’t photographing people or things—they’re capturing moments.

The journey begins at the Memphis airport. Teller takes Korine’s picture; his arms are wide open. He’s ready to get on the road. They take off to get Eggleston. What they see out the window is a desperate American landscape. Abandoned cars and houses. Graveyards and gas stations. They stay a night or two at the Peabody Hotel in Memphis and drive south. Stop in Greenwood, Mississippi and visit with Eggleston’s cousin Maude Schuyler Clay and her husband, Langdon, both accomplished photographers in their own right. They drive on to a gun store with a giant pink gorilla out front, eat at a Japanese steakhouse, spend the night in a motel, and return to the Peabody in Memphis. Along the way they stop and find nothing.

The Delta they photograph is largely untouched by modernity, a whole way of life crumbling from decades of neglect. A place that has changed slowly. Poverty and wealth that can be traced straight back to the Civil War. But they find a complicated elegance there. Empty downtowns, freshly killed deer draining of blood, assault rifles, and sunsets. To Korine, a part-time Southerner, and Teller, a German, these scenes feel exotic and almost surreal. A dog tied up and a Jesus statue—the images would likely seem equally alien to art lovers in New York and LA. But to those who spend their lives in the Delta, it is the gray, quiet despair of the waning years of capitalism and the economic realities of a racial caste system. Extreme tackiness of wealth contrasts the deep desolation of indigence.

William Eggleston 414 is a moving portrait of an aging seeker. The final photos in the book show Eggleston talking with someone at a Mexican restaurant. She could be an old friend or a complete stranger, a fan—he seems to take great care in visiting with her regardless. He signs an autograph. Then at the hotel, he finds a grand piano in the hotel lobby and plays. Later, his son Winston takes off his father’s shoes, and after a few drinks in the hotel room, Eggleston pantomimes his earlier musical performance. His arms waving across an invisible keyboard. We can almost hear him humming along with his improvised tune. He’s graceful despite the booze, in the moment, trying to impart the truth.

I lived in Mississippi for many years, and until 2020 I’ve gone back regularly. This will be the longest I’ve been away, not a great loss in a year of extreme suffering. But there’s something absolutely transcendent and profoundly awful about Mississippi that I miss with each passing day. The back roads are the essence of nowhere in an age we need to get lost more often. William Eggleston 414 helped me feel wonderfully adrift again and made me dream of the time when we’ll all return to the search.

Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer describes “the search” (for God, for meaning?) this way: “The search is what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life.” Eggleston, and by extension Korine and Teller, seem to instead find transcendence in that very everydayness. Their book is a sublime depiction of seekers seeking, never arriving. The destination isn’t important, never was. The thing is to keep hunting for actual beauty in the dying world.

Michael Bible is the author of the novels Sophia, Empire of Light, and The Ancient Hours.

All photos: Harmony Korine & Juergen Teller, William Eggleston 414, published by Steidl.

More Reviews