Dark Hilarity

Reviews

By Carmen Boullosa (Translated by Samantha Schnee)

“We’re always complaining about our Judeo-Christian heritage and our inclination to masochism and criticism,” the Mexican writer Margo Glantz wrote in Las genealogías. And it’s absolutely true, at least for Mexicans; we even complain about our complaints.

In Spanish, these two words together, quejidos quejamos (literally, “we complain our complaints”), have the effect of ay-ay-ay-ay!—the sound of being wounded to the core that, just like in famous ranchera songs, is pronounced at the top of one’s lungs. On the other hand, quejamos quejidos can be loud and joyful pronouncements, much like Luis Felipe Fabre’s novel: a song sung with all one’s might, a celebration, a dance. Recital of the Dark Verses is a cacophonous delight. This is a playful book, hilarious in its wild abandon; it’s a sheer pleasure to read—and the very opposite of what Margo Glantz describes so clearly. Fabre’s novel goes far beyond quejidos of either variety.

In the final decade of the sixteenth century the body of a great poet-monk, Fray Juan de la Cruz (known in English as Saint John of the Cross), is exhumed on the Iberian Peninsula a year after his death due to illness. Though his body was infected and covered in sores when he died, a month after his death the body has not decomposed; it even exudes “the scent of saintliness. The gentlest of perfumes which stirs in the soul yearnings, burnings, and zeal,” a scent best appreciated from afar “like distant jasmine” or, according to others, “Oriental aromas.”

“The aromatic clamor” of this incorruptible body is the leitmotif of the novel, accompanied by the body of San Juan de la Cruz’s most famous poem, “Noche oscura del alma” (translated by Heather Cleary as “On a Dark Night”):

En una noche oscura

con ansias en amores inflamada

¡oh, dichosa ventura!

salí sin ser notada

estando ya mi casa sosegada.

On a pitch-dark night

by love’s yearnings kindled

—oh wondrous delight!—

I slipped out unminded

for my house had gone quiet.

The plot is simple: a small group of royal servants and men of the cloth transports the incorruptible body of (San) Juan de la Cruz from the Carmelite monastery of Úbeda to the city of Segovia. Throughout the length of the journey pieces of his corpse are cut off to satisfy the demand for his remains; his corpse is precious—it is endowed with miraculous properties. There is neither town nor city where the procession passes without a battle for even the smallest piece of his holy remains, while a variety of other hilarious adventures take place.

As the mission to save this mutilating, mutilated, miraculous cadaver unfolds, the novel gains a renewable energy from the corpse of (San) Juan de la Cruz: the flame it produces illuminates a wild revelry—a pachanga.

The tone of the novel is satirical, and since the journey begins in Úbeda, I’d like to mention one detail in that town’s basilica (Santa María de los Reales Alcázares), a detail known as “The Hummer of Santa Maria”: this capital of a column supporting a vault in the cloisters depicts a half-human creature practicing fellatio on a monkey. The adventures of the living protagonists of this novel and its tone are just as outrageous.

In this wild ride of a novel, the author takes us on a journey through the verses of San Juan de la Cruz’s most famous poem, interpreting it a la queer and a la sexual. Widely considered profoundly religious, even mystical, it acquires a celebratory, orgiastic tone in Fabre’s novel. What “happens” through the verses is not a mystical experience, but rather a coitus narrated by the woman that’s living through it. The novel speeds along in a coital rhythm, perhaps erotically and without question raucously—part joyous discourse on the poem, part bacchanal, part satire and adventure.

Recital of the Dark Verses has both the momentum and feeling of Cervantes’s adventures—its narrative branches and their foliage are descended from Quixote, but here they’re driven by Fabre’s reading of San Juan de la Cruz’s best poem. Some literary critics draw connections between a work and the life of its author, but in this case—where the author marries the journey of the cadaver with a reading of this poem—the connection is between the poem and the corpse of its author.

Fabre’s intention is neither to offer a cursory reading of the poem nor to fleece it of its mystery, but rather to offer the personal interpretation by one of his characters (alter ego or no). Some might consider Recital of the Dark Verses literary sacrilege, while others might think it commits religious sacrilege; for me it’s both—and an exuberant storytelling burlesque.

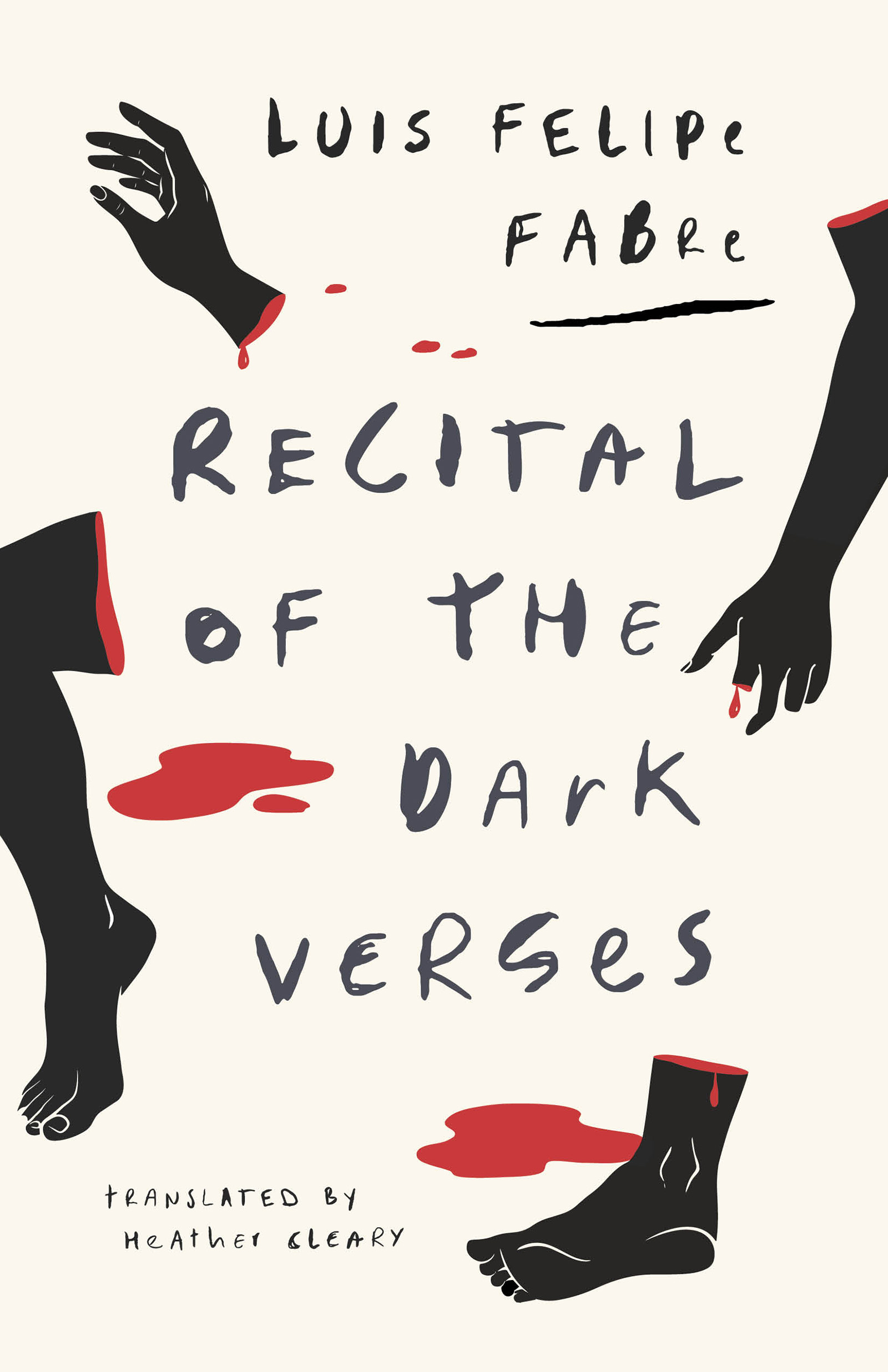

The author is in full command of his tale and delivers what remains of the saint’s cadaver safely to its destination without any further losses beyond the plentiful, inevitable donations that the procession leaves behind in order to proceed. At times, the many riches of San Juan de la Cruz’s poetry are obscured in part by the hilarity and uproar Fabre’s plot creates. At times, San Juan’s verses are our guide, and at others they form the spine of the novel. At times, it may seem as if the reins of the story are about to snap. But I don’t want to end on such a note; this magnificent novel that I thoroughly enjoyed deserves better, as does this brilliant translation by Heather Cleary. This joy of a book is an admirably insolent work by a literary author who is admired and esteemed by many, including me: Luis Felipe Fabre.

Carmen Boullosa—a Cullman Center, a Guggenheim, a Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst, and a Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes Fellow—was born in Mexico City in 1954. She’s a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, and artist, and has been a professor at New York University, Columbia University, City College, City University of New York, Georgetown, and other institutions. She’s now at Macaulay Honors College—City University of New York. The New York Public Library acquired her papers and artist books. More than a dozen books and over ninety dissertations have been written about her work.

Samantha Schnee is the founding editor of Words Without Borders, dedicated to publishing the world’s best literature translated into English. Her translation of Boullosa’s Texas: The Great Theft was longlisted for the International Dublin Literary Award and shortlisted for the PEN America Translation Prize. She won the Gulf Coast Prize in Translation for her work on Boullosa’s El complot de los Románticos.

More Reviews