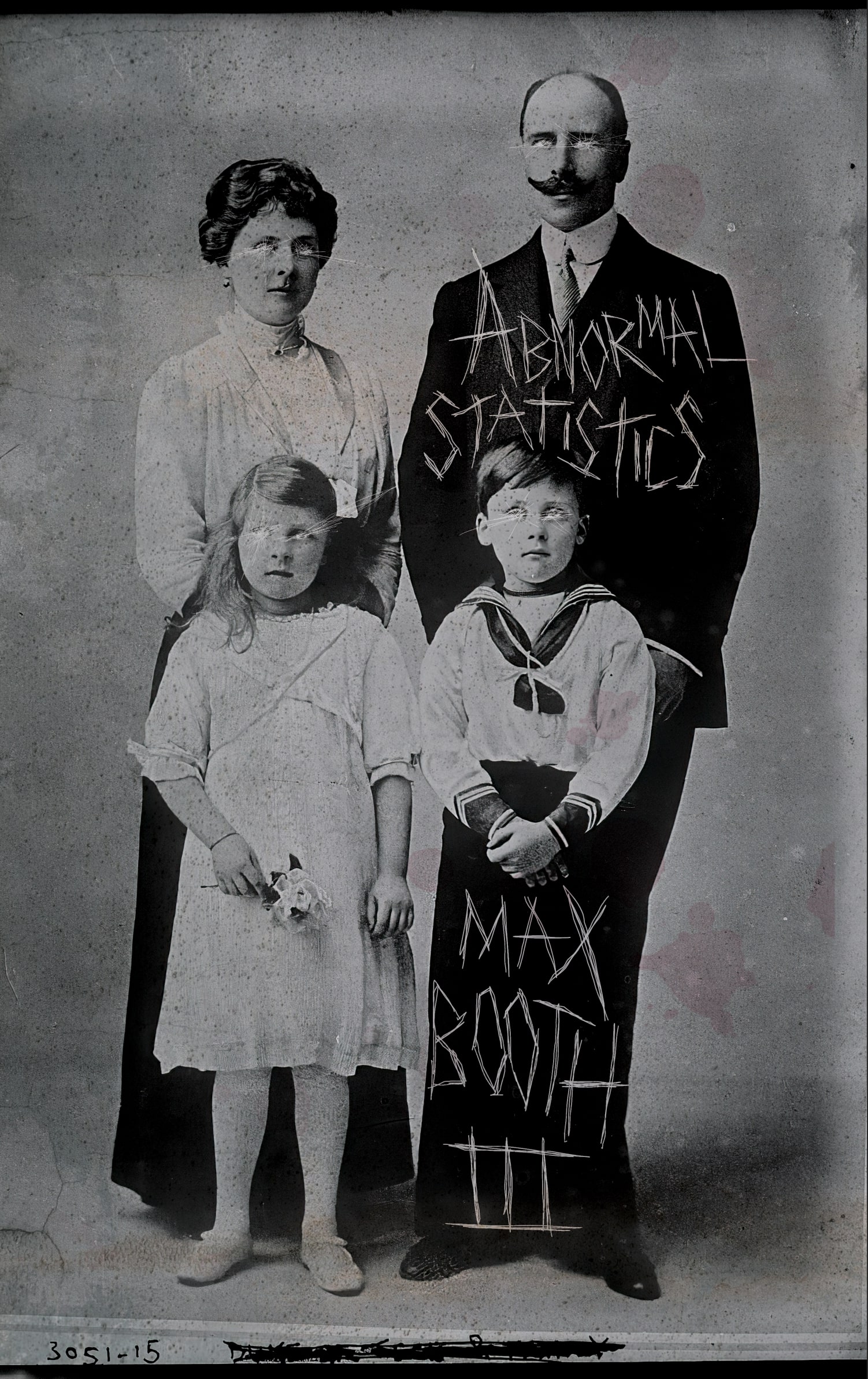

The Modern-Day Family in Bleak, Bloody Freefall

Reviews

By Adrian Van Young

“The baby is dead. It took only a few seconds,” begins Leila Slimani’s 2018 worldwide bestselling novel The Perfect Nanny, a French chiller about a Parisian couple who welcome an unstable live-in nanny into their lives only to face traumatic, life-altering consequences. Straightforward and simple, yet appallingly shocking, those lines never quite leave the reader’s bruised psyche before their bad vibes come home to roost; the book ends, in some ways, worse than it began. And despite the fact we’re aware of that ending from page one, the rest still feels transgressive, yet stately—inevitable.

Like Slimani’s novel, the stories in Max Booth III’s new collection, Abnormal Statistics (Apocalypse Party, 2023), throw down a similar gauntlet in many of their openings, at which Booth is very good. Take the beginning of “You Are My Neighbor,” one of the most successful tales in Abnormal Statistics, where Booth’s narrator, a criminally neglected suburban teenager, tells us:

I used to break windows. One window in particular, really. Our neighbor had a basement and we didn’t, and I always thought that was unfair. Growing up, all I wanted was to live in a basement and invite all the kids from school to hang out and drink beer with me while listening to Black Sabbath. But we didn’t have a basement and nobody came over because Mom was too embarrassed by how messy the house was and Dad was paranoid someone would swipe their oxys while he was asleep.

Here, in the same full-throated breath, Booth conjures the recklessness of a compulsive vandal and the murdery ominousness of a neighbor’s basement against a backdrop of suburban malaise where boredom leads to darker doings. Yet Booth’s paragraph also has a sublevel—a figurative basement, if you will: the teenage narrator lives in squalor because the kid’s parents are addicted to opiates. His father has pawned his cherished Xbox; mom and dad are unconscious from pills on the couch. Suddenly, the reader finds herself as invested in the narrator’s plight as she is in the story’s dread-soaked promise, which in “You Are My Neighbor” involves (at the risk of some partial spoilers) an Omelas-like degraded child, a friendship, and a transformation.

“Boy Takes After His Mother,” a blackly amusing tale and another of the collection’s highlights, begins in a similar manner: “Mommy used to kill people before I was born, but I’m not supposed to talk about it.” And not much—not even The Perfect Nanny—beats the opening of Booth’s story “In the Attic of the Universe” for its aura of sheer transgressive horror: “Stuart held the pistol up to his two-year-old son’s skull and closed his eyes.”

A little gratuitous? Yes, perhaps. Though I’m guessing that Max Booth would scoff at such judgments; gratuitousness—the taboo-smashing, splatterpunk kind—is the water Booth swims in. And even though “In the Attic of the Universe,” a sort of sentimental take on the zombie narrative, isn’t one of the collection’s strongest offerings, it is sharply illustrative of yet another helpful crossover between Slimani and Booth that informs Abnormal Statistics’ vision: the modern-day family in bleak, bloody freefall.

Here is where Max Booth III, author of We Need to Do Something (2020) and Maggots Screaming! (2022), really shines. Like Jack Ketchum or Bret Easton Ellis or (believe it or not) early Ian McEwan, Booth is a shocking, absorbing, and sick-minded chronicler of the relationships that govern loved ones, among whom violence (physical, emotional, psychological) comes to seem as normalized as the bonds that would seem to prevent it. Fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, in-laws and neighbors, and especially children—none are blameless, none are spared.

In “Indiana Death Song”—the hitherto unpublished, slow-burn novella that opens Abnormal Statistics and by far its strongest tale—another neglected teen with another set of dark-hearted addict parents lives an anesthetizing, transient existence in a casino hotel in Indiana, only to find himself in the grip of a real-life disorder called “Truman Show syndrome” (look it up!), every day more obsessed with a grim suicide that took place on the hotel’s grounds. In “Scraps,” an alcoholic ex-con with an unspeakable shame clouding his heart welcomes a People Under the Stairs-esque posse of feral boy-children into his life, prompting a weird, unexpected redemption. “Fish,” one of the collection’s most grandly perverse yet nonetheless arresting stories, a horny teenage boy (Booth’s stories, while not wholly absent of women, are more inclined to privilege men) who takes up with his sketchy, grownup neighbor, lending icky new vibes to the term “chosen family.” And in “Abduction (Reprise),” a late gem, a mother reveals to her grown-up son the story of his near abduction at a Sam’s Club, a recovered trauma that consumes him.

Unfortunately as promising as, say, the first half of many of these stories are, even the strongest among them have a tendency toward erratic third-act spurts of violence that don’t always seem intrinsic to their troubled protagonists, even when they’re in first person. The bloodshed in these stories feels almost pro forma. Herein lies the difference between the masterful, paranoiac “familial horror” of a story like “Indiana Death Song” and a piece of gotcha-exploitation like “Every Breath Is a Choice” (where a vengeful father sends the destructive energy of his son’s murder and his wife’s rape squarely back on the psycho responsible for it)—both of them conceived by Booth. Sometimes, like one of his reckless protags, Booth snatches defeat out of victory’s jaws. He can be terrifying, even deeply affecting, when he lets his nightmares seethe and fester, less so when he bids them to splatter and spurt.

Still, the singularity of vision and the lurid absorption that inform the stories in Abnormal Statistics are impressive. In Max Booth III’s tales, home is still where the heart is—best of all if that heart is ripped out of your chest.

Adrian Van Young is the author of three books of fiction: the story collection, The Man Who Noticed Everything (Black Lawrence Press), the novel, Shadows in Summerland (Open Road Media), and the forthcoming collection, Midnight Self (Black Lawrence Press in October 2023). His fiction, non-fiction, and criticism have been published or are forthcoming in Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading, Black Warrior Review, Conjunctions, Guernica, Slate, BOMB, Granta, McSweeney’s and The New Yorker online, among others.

More Reviews