A Wild Danse Macabre

Reviews

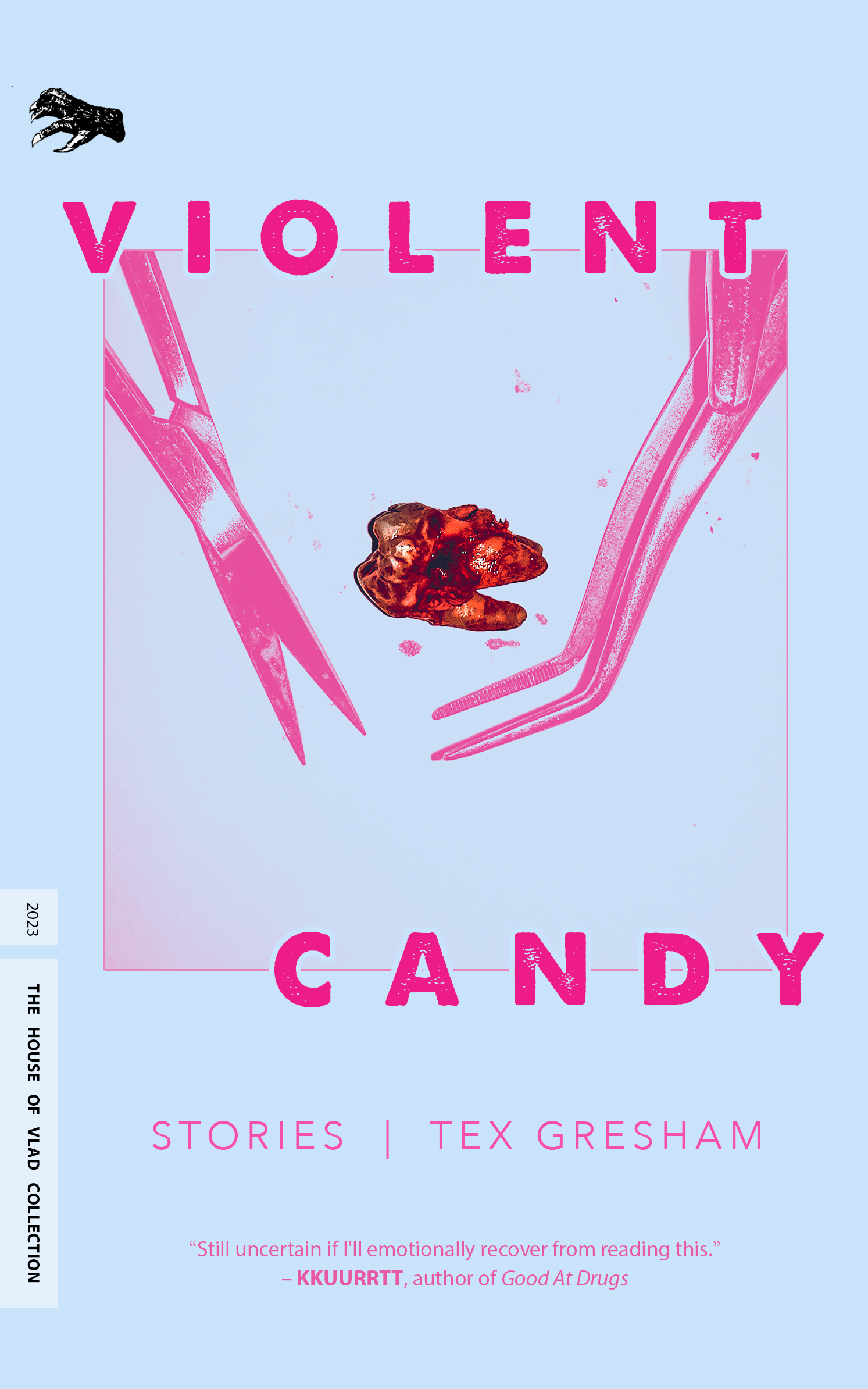

By Conor Hultman

The problem with recommending horror to anybody is that the feeling itself is a deep well with a hundred sources. A person who likes (in this genre, meaning “is pleasurably disturbed by”) Dracula won’t necessarily dig The Girl Next Door. Thomas Ligotti, Stephen King, and Poppy Z. Brite (now going by Billy Martin) could have a perfect circle of appreciation in one group of fans, or three discrete camps in another, and these writers are contemporaries. The issue isn’t one of content, typically, but affect. A ghost story can be lighthearted, chilling, gore soaked, suspenseful, cryptic, or emotional, depending on the treatment. Attempts have been made to make this problem easier with subgenres—weird fiction, gothic, splatterpunk, etc. But the question still must be answered: What kind of horror book is this?

Tex Gresham clues you in on the brand of scares waiting for you in Violent Candy with the very first story, “Iris.” The setup comes in the second paragraph:

Picture this: two or three doctors standing at the foot of a hospital bed. There’s a young woman in this bed. But you wouldn’t be able to tell this if I hadn’t just told you. Why? Well, her head is totally covered in surgical gauze. It’s splotched with rust-colored stains. From blood that’s seeping through.

The monster in this story, “the Shape,” gets two short sentences of confused, suggestive description: “It is human-shaped. It has something long and loud and violent in its hands.” The end of events is as blunt as it is disquieting:

The doctors show her an x-ray of what’s left of her face. They say skin graft, bone graft, reconstruction. The amount of tissue missing is disproportionate to the amount remaining. She translates this to Hey lady, most of your goddamn face is missing and what’s left looks like the guts a hunter leaves behind when he field-dresses a kill.

This is horror meant to unsettle. This is for pinching stomachs, freezing blood, and fraying nerves. Take as needed, preferably on an empty stomach. Keep out of reach of children.

With this diagnosis in mind, consider three vital aspects of horror fiction that Gresham repeatedly succeeds in delivering.

1. Show less.

If the source of horror is allowed to be seen for an extended period, one becomes familiar with it. From familiarity proceeds comfort, the death knell of a scare. None of these stories lets the reader get comfortable. “Stain,” about a frat kid aspiring to terrorism, keeps the subject’s motive a dripping red question mark. From “Bodie wanted to do something bad” to the very end, his interior state is as occluded as a murderer’s often is in real life, and therefore as horrifying. The title story is about a violent gang wreaking chaos on Halloween 1992. Throughout, the narrator frames the events with frantic commentary in the present that obscures more than it reveals. The brutality elevates and then coheres around a lost old woman, “shrunken and exhausted, blank like she’s just eaten a gallon of paint she thought was yogurt.” After the conclusive atrocity, the last piece of reflection is terrifying for its long-building ambiguity: “but what I can’t escape—and what I see in the mirror—is her face—because she knew we were leaving her to die.” Whether it’s the shady underpinnings of a wealthy golf course, or the circumstances that lead an old friend into hard drugs, Gresham never shows all his cards. Sometimes not even the edge of one. Every story is endlessly rereadable for this.

2. Funny is scarier.

Humor and horror have a delicate relationship. Go too far on the laughs and you enter “comedy horror” territory; respectable in its own right, but unlikely to raise any light bills. Be too self-serious, however, and you risk something worse, the unsympathetic laugh. Violent Candy deftly and frequently introduces the right amount of hilarity. “Lovebird” has as a main plot point a man falling in mutual erotic love with an ostrich. If the reader of this review is unconvinced they can be left shocked and emotionally drained by such a premise, I promise you, you will be eating your words. Body horror is woven in in an uncanny way as the absurdities are slowly introduced. By the ultimate (every possible pun apparently intended) cockfight, there is no state to be in but heartfelt grief and disgust. Whether it’s taking a job cross-dressing as a rich couple’s dead child, or going on an odyssey to replace your friend’s mom’s sex toy, Violent Candy’s terror locus is balanced between light and dark, doing a wild danse macabre.

3. Parenthood is full of anxiety.

Gresham, like the best giallo directors, understands that horror can breed most productively in the domestic. That is, wherever readers think they are safe, therein lies the darkest material. “It’s a Small World” is set in, of course, the Florida theme park with the appropriately annoying ride. What most know as “The Happiest Place on Earth,” the narrator, a parent with their young daughter, sees as a potential underworld of imperceptible child abductors. The narrator watches “a woman in panic” trying to find her daughter: “She shouts the name Blossom into the crowd. No one notices her.” Their own daughter having a floral name, Daisy, the narrator is drawn into an obsessive, yet distant, observation of this collectively ignored scene. The narrator buys Daisy an ice cream cone, moves away from the mother, goes back and forth about what to do, what they can do. Then, the narrator sees “a little blonde girl on the verge of hysterical,” a man “pulling her in the direction of the park’s main exit.” Tortured over the possibility of unrelated circumstance versus active kidnapping, the narrator has only a minute to wonder how to know if this man is the girl’s parent, before Daisy runs off to see the mouse parade begin. The paranoia for abuse boils the narrator into rage: “You know there’s a place in this park where they keep the children . . . mold them to not just believe in the magic but to worship it . . . you know the children will be lobotomized.” Children provide the tension in several other stories, but not in the generic “kid with a killer’s mind” cliche where weaker horror reaches. Rather, children are used for their real-world sympathetic dimension; it is frightening to have to care for something so vulnerable. A teen boy is possessed by video games, a young girl reveals to her stepfather her accidental homicide, and in each case it is their need to be protected that disturbs.

Besides children, other unlikely sources for dread include peaches, herbicide, movie theaters, and a mouse found in delivery pizza. Gresham is working real straw-into-gold magic here. It’s unwise to spoil more. Any given story can send the reader shaking into public, wary to be alone, wary not to be. Buy Violent Candy this Halloween, give it out to friends, and let it get stuck in your teeth. Something this sickly sweet probably shouldn’t be filling, but it is.

Conor Hultman lives in Oxford, Mississippi.

More Reviews