Now All Your Songs Sound Wrong | An Interview with Ed Madden

Interviews

By Brad Richard

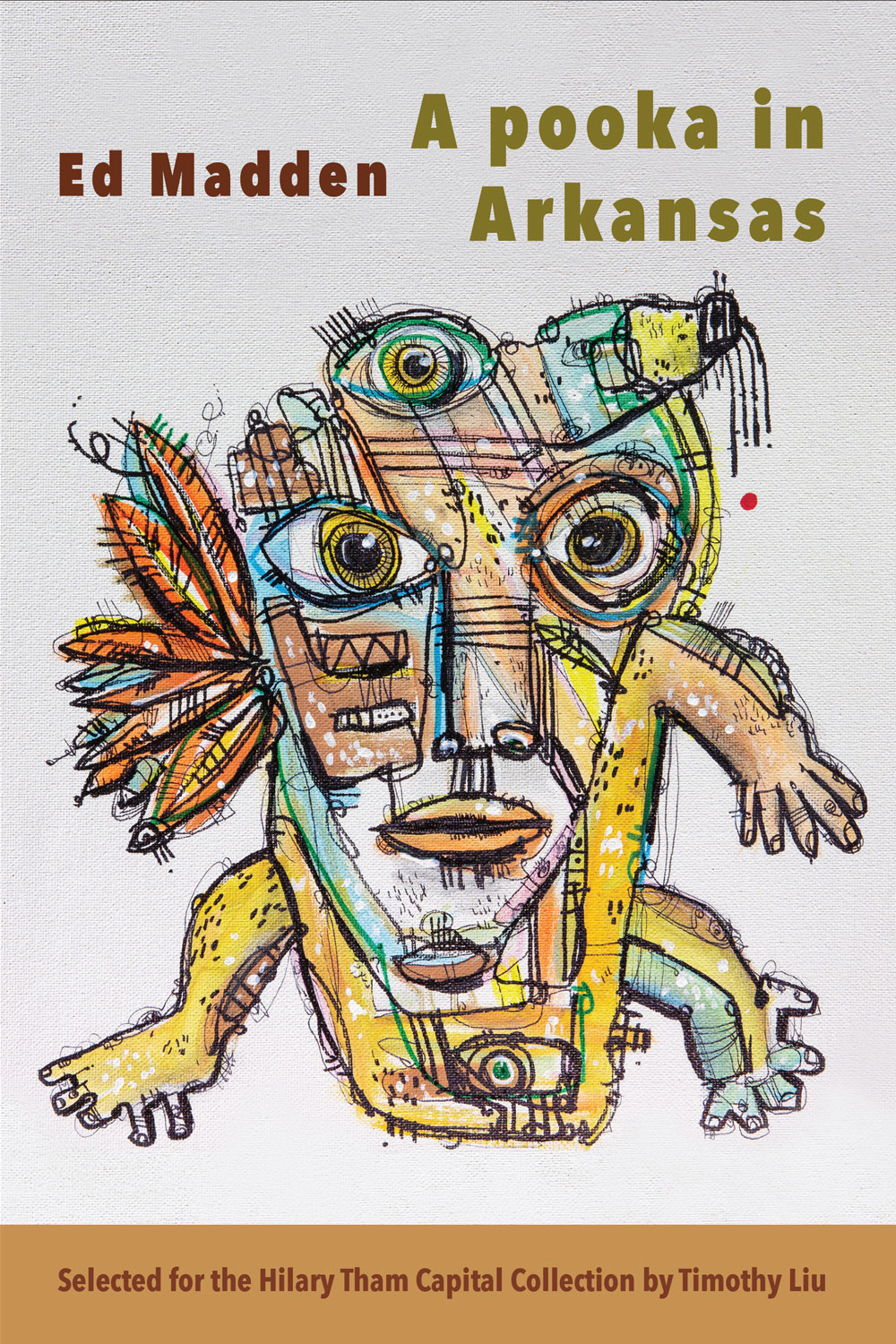

“What have we to do with who we are?” begins Philip Martin’s excellent, thoughtful review of Ed Madden’s most recent collection of poems, A pooka in Arkansas (The Word Works, 2023). It’s a tricky question, one that Madden’s poems have probed and reimagined over the course of his earlier books: Signals (Univ. of South Carolina Press, 2008), Prodigal: Variations (Lethe, 2011), Nest (Salmon Poetry, 2014), and Ark (Sibling Rivalry, 2016). In his latest book, Madden explores the problem of becoming who we are via the pooka (in Irish, púca), an Irish trickster, shapeshifter, and mischief-maker. Best treat him well, or who knows what tricks he’ll play.

Madden’s work has always been intensely lyrical, and song itself is a prominent motif in Pooka. In “Rules for coming back,” he writes:

You used to sing the old songs.

They were so melodious.

You used to sing the old songs.

Now all your songs sound wrong.

That wrongness is who he is, of course: the wrongness of sexuality and difference that led him to be rejected by his conservative, very religious family. He went on to find joy in his sexuality and other pursuits, but still carried the shame he’d been taught was his due. It’s a painfully familiar, complicated dynamic, the ruptures and raptures of which form the substance of many of Madden’s poems, as do his love of Ireland and Irish literature, his long marriage, and his many honors, including being the inaugural poet laureate of Columbia, South Carolina, from 2015 through 2022.

This interview was completed through email and Zoom conversations.

Brad Richard: Ed, I think the pooka wants us to begin by acknowledging the spooky season we’ve entered. Can you tell us more about what this spirit means to you and why he would love Halloween?

Ed Madden: Sure! This is his time of the year, end of the harvest and spirits walking among us. In Irish folklore, the púca, or pooka, is a shapeshifter and trickster, a goblin. Sometimes nice, often scary. Shows up sometimes as a big black horse on a dark country road and throws you on his back and takes you on a wild ride to places you’d never planned (or maybe even wanted) to go. Or sneaks in your house late at night and does your chores—unless you ask or expect it, and then he’s gone. At the end of the harvest season, he spits or pisses on the berries, marking them. Saying: they’re mine now. November 1 is the púca’s day. Harvest ends at Samhain, the Celtic origin of Halloween, when the border between this world and the other is thin, and the dead might visit their old homes. There were divination games, carved vegetables (turnips, not pumpkins) to scare away spirits, treats left out for the fairies. And there he is, storyteller and troublemaker, showing up as a horse or dog or an eagle or an old man with goat’s ears.

Even though, growing up, religious identity was way more important than my family’s Irish and Scots-Irish heritage, the pooka has had hold on my imagination for a while. Sometimes we change who we are to fit where we are or where we are going. And sometimes we are tricked into being someone we’re not, and sometimes we have to be scared into being the person we were meant to be. For me the pooka is all of that, shapeshifting and becoming and being scared to death of where we know we need to go.

BR: When reading (and editing) A pooka in Arkansas, I felt like the pooka was everywhere in these poems, but you only name him in the title poem. Naming him once seems to be all that’s required to evoke this spirit who might literally piss on categories and proprieties—yeah, as a juvenile prank, but maybe also to say, like the dog at the end of that poem, “How far do you think we’ll go tonight?” Can you say more about how you chose to make use of the pooka’s presence?

EM: When I started working on this book, I knew that poem was the title poem. This strange shapeshifter from the past sharpening my own focus on the places I’m from. That little dog showing up on an empty country road at dusk, when my dad was dying of cancer inside the house, and none of us knowing how far we—or he—would go that night. I was working on the manuscript on writing retreat in the mountains of northeast Georgia (at the Hambidge Center). There was a tackboard wall in my cabin. I put that poem in the center and started tacking up others around it, and it felt like the poems were arranging themselves on the wall like metal shavings around a magnet. Animals, memories, shame, shapeshifters, fairy tales. For days a giant wolf spider was splayed over the front door like an apotropaic emblem. I also thought, what better figure for a queer kid growing up in rural fundamentalism than a shapeshifter. Maybe everyone feels like that sometimes, like we’re trying on different skins to hide who we really are, but there was something darker and scarier here, something shameful. I also kept thinking about those terrifying or initiatory encounters we have—sexual, social, spiritual—that take us places and teach us things and push us to become what we never imagined possible. The big horse you don’t know how to mount or dismount, the strange man with hairy ears telling you things that make you wonder. It was in that cabin, out in the darkness and the trees, that big spider over the door and the camp’s resident black cat stopping by my patio at night—never stopping for long, always headed somewhere—it was there that I wrote poems about meeting the púca. A couple of those poems made their way into the book. I was staring into the darkness, staring into the past, taking it in. I remember I was using Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies creativity card deck for random prompts, and two cards felt like omens more than prompts: Distorting time. And Go outside. Shut the door. Damn.

BR: I love the vigilant presence of that wolf spider. In your poems, the pooka is a very carnal presence—not exactly sexual, but close. I find a lot of eroticism in all of your work, sometimes in an overt way but more often as a very strong undercurrent. You write images that make me keenly aware of being in a body and wanting to honor (and to share) what it knows and what it desires, sometimes in contexts where it’s “out of place”—which makes it all the more intriguing. What role do you see the erotic playing in your work?

EM: The pooka does feel carnal, doesn’t it? Doesn’t he? Have you seen the statue of the púca that was made for the Irish town of Ennistymon—a man’s body twisting up into the head of a horse? The tension and the writhing energy in that body. It’s amazing. And so scary the local priest convinced the town to turn it down, and now it’s sequestered in a folklore museum rather than standing where the road enters the village.

I think the erotic drives a lot of my writing, but I appreciate how you bend attention more toward being in a body more broadly. I mean, isn’t that a fundamental element—or problem—for those of us who grew up queer in times and places where there was no representation of queer desires other than shame and some unspoken but not unsensed evil. Or if spoken, couched in hellfire and moral panic. The flesh is evil, the spirit good, and yet the body does what it does, and we are our bodies. I remember the title of that groundbreaking study of gay poetry by Gregory Woods that I read in graduate school: Articulate Flesh. It’s not the word made flesh, but flesh made word, becoming articulate. Gay poets, like so many other marginalized poets, put the body and identity back at the center. I think that’s part of my journey as a poet: how do I put my experiences into language, especially those experiences and desires that feel definitional but I grew up thinking should never be said. Or done. Or known.

BR: Yes! It’s like we’ve learned a very physical lyricism, one taught by the body—or as if the body’s knowledge is a kind of prayer we’re setting down.

EM: The body’s knowledge, which is always still mediated somehow, right? You know, later this month I’m getting a tattoo. It’s something I’ve been thinking about for a long time. I’m using an emblem from a piece of fabric about a yard square that was passed down in my family. I don’t know a lot about it. It’s a square of moth-bit green felt, embroidered with red, yellow, and a metallic silver thread. There’s a gorgeous little harp in each corner, and in the center a kind of abstract swirl with a small yellow flower over it. There are differing stories about where it came from, but my dad called it a “prayer cloth” and told me that it had been prayed over by a “tinker” or a faith healer for my grandfather’s older brother, who died of pneumonia in his teens in—I think—1912. After his death, my great-grandmother kept the cloth, and it ended up in my aunt’s garage. She told me no one else wanted it. My dad’s reference to a “tinker”—a traveling metalsmith but also a derogatory name for Irish Travellers—made me wonder if there might be an Irish connection. A scholar in Galway said that it looks like a cloth Travellers would spread on a table for transactions and fortune telling. He said that swirl in the center is the map of a route—roads, river crossings. The flower was the North Star.

So, I’m getting that design tattooed on my back. It feels right. An emblem of family and history, migration and prayer. Articulate flesh.

BR: There’s a line I love “Burning the fields,” my favorite poem in the book: “Sometimes we touch each other as we pass, hoping one of us will be healed.”

EM: At some level, I had in mind the story of Jesus and the woman with “an issue of blood” (as the King James Version puts it). She had been bleeding for twelve years—probably prolonged menstrual bleeding. And under religious law she would have been considered unclean—untouchable—and anyone who touched her would also have been unclean. For twelve years. But she knows that if she just touches the hem of his robe she will be healed. It’s an amazing story, and I don’t ever remember it being explained—other than as an example of faith—when I was growing up in the church. We never talked about the story’s critique of religious laws that treat some bodies as unclean and untouchable. We talked about Jesus being with lepers, sure, and maybe “sinful” women, but menstruation would have been beyond the pale for polite Christian study. Coming out in the age of AIDS made that story even more important to me. Bodies deemed untouchable or unclean by a dominant culture. So that’s the story behind the line, but I was also thinking more broadly about touch and healing. Erotic, of course, but more than that. The reciprocity of touch, and feeling at home in your own body, in part because of that finally found freedom to touch and to be touched.

I have to say thank you for asking about that line. I never read that poem, not even excerpts, during readings—it’s too long, and I’m not sure how well it would work. And I’ve never talked about that line before. Or that story.

Can I ask you about a couple of your own poems? When I was reading the manuscript of your new book, Turned Earth, I was shaken by the opening poem. I mean, there’s something really emphatic and settled about starting a book with a poem called “How I Am Whole,” but the book is about not being whole. It’s a book about dealing with loss and grief, and the poem feels more tentative than convinced. You say, “my body / keeps getting me lost in things.”

BR: Thank you for asking about that poem—it’s one that means a lot to me, and it took a very long time to get it right. And yes, that certainty you note is paradoxically tentative because the poem is so much about being in time—in the body and in art. I’m trying to grasp those moments, usually ones of unexpected joy and pleasure, when feeling overrides thinking and all the Cartesian boundaries fall away. Well! Maybe not anything quite that grand. After all, the poem mentions cooking, being in a classroom, smelling a carnation, feeling sunlight on one’s skin—not experiences that appear inherently sublime. No visions, no annunciations. What I most wanted to recapture was the memory the poem describes that came back to me when an artist asked me for the story of my body: I was six or seven, standing one afternoon by the screen door of our porch in Mobile, and the sunlight on my skin was so marvelous, it made me intensely conscious of everything else I was feeling, a consciousness that was a special kind of wholeness. And I really do remember thinking, “I want to remember this.” And that memory of wanting to remember is, I think, its own kind of wholeness.

EM: The other poem I wanted to ask about is “Lapis Lazuli.” It’s a post-COVID poem. I remember moments like what you describe, right after the world opened up again, being in a crowded place and thinking about how it had been empty only months before. But it also feels like such a pointed response to Yeats. He thinks art is timeless, but the polished rock in your pocket reminds you, “I’m still here.” And that line also made me think of Paul Monette’s work in Love Alone, his elegies for his partner who had died of AIDS, and his own poem that ends “I’m still here.”

BR: Yes, an awareness of, and gratitude for, being alive in the midst of crushing grief is what motivated this poem. I’d been hanging out with a friend at a conference in Philadelphia. We visited the Reading Terminal Market, and it was packed. I hadn’t had to maneuver through a crowd like that for two years, which made me think of what this space would have been like during lockdown. We went to an apothecary shop, where my friend was excited to find items she’d been looking for. I wanted a souvenir of the day, so, thinking of Yeats, I bought that piece of lapis. When I came home, I pulled down my collected Yeats, reread that poem—and hated it! The whole thing struck me as smug and selfish in its glorification of the supposed timelessness of art. Sorry, Yeats: it’s mortality itself that makes me love the world, and that makes me appreciate the fragility of all beautiful things.

I’m going to use Yeats as an opportunity to pivot back to Ed Madden. I know your connections to Ireland and to the Irish poetry scene have been very valuable to you—not just as family heritage but as a writer and literary scholar. Can you recommend some contemporary Irish poets that American readers might not know?

EM: Three poets: Seán Hewitt, extraordinary queer poet of the body and nature and fathers and sons and partners. And Annemarie Ní Churreáin, gorgeous poet of kinship and folklore and ways that culture can bend and break and sometimes mend families. Also Gail McConnell, whose book The Sun Is Open is so experimental and yet so deeply moving at the same time—something I don’t think happens much. A book about sifting through the evidence of her father’s murder and realizing all the ways that religion and politics shaped and warped and redacted the story.

BR: That kind of shaping and warping, and finding one’s way out of it through poetry, seems to be one of our themes here. I think again of your very religious upbringing, and how you draw on it throughout your work, referencing its archetypes, yielding to its cadences. The more I know, particularly from Ark and Pooka, the more moved I am by the ways you use that material. Can you say a little about your relationship to that legacy, personally and as a poet?

EM: The stories and language of that culture are integral to who I am. Even if I learned shame and self-hatred there, I also learned what community could be. I grew up in an extended farm family, most of us all going to the same church, and those experiences inevitably structure and color my sense of what belonging can mean. More than that, I think that language is part of my language: the cadences and syntax and images of that culture—the King James Bible and all those hymns and songs from summer camp and Sunday school—they are part of who I am and how I think. It’s the culture that made me. But I’m going to adapt that to who I am now. I’ve shed that skin, and I can still sing the same songs and speak the tongue, but I am a different beast now.

Brad Richard’s fifth full-length collection, Turned Earth, is forthcoming from LSU Press in spring 2025. His other publications include Parasite Kingdom (The Word Works, 2019, winner of the 2018 Tenth Gate Prize) and the chapbook In Place (Seven Kitchens, 2022, winner of the 2021 Robin Becker Series Prize). He has taught creative writing at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts, the Willow School (whose creative writing program he founded and directed), Louisiana State University, and Tulane University. He currently teaches for the New Orleans Writers Workshop and the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop for Teachers, and he serves as series editor of the Hilary Tham Capital Collection from The Word Works. He lives, writes, and gardens in New Orleans.

More Interviews