Pornographic Noir

Reviews

By Conor Hultman

What separates the horrors of Hell from the struggles of Purgatory is the presence of hope—for absolution, for change, for an ending. In a narrative, this constitutes the difference between a work of nihilism and a work of conviction, or what less self-conscious generations called “moral fiction.” Moral fictions often take place in abattoirs and oubliettes, where the battles with the highest stakes occur. But good moral fiction doesn’t moralize. The weight and direction of its conscience can be felt, however obliquely, from every scene and description. It’s a cloud whose saturation is its substance.

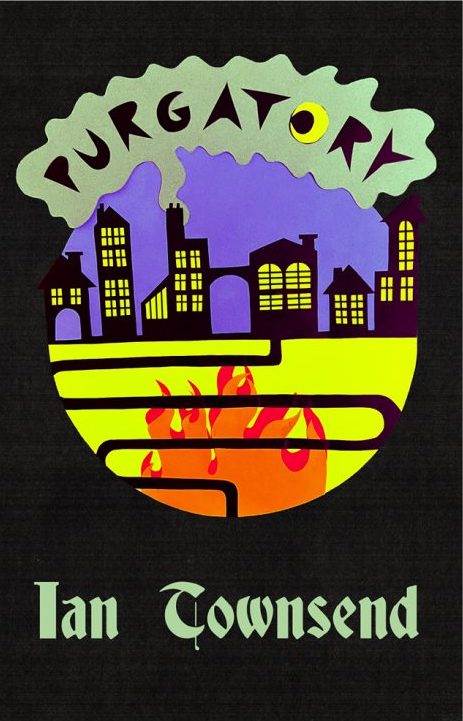

Ian Townsend’s Purgatory is an enchanting novel for such a subtlety. The novel’s cynical, nihilistic exterior narrative is really an affective capsule meant to deliver earnestness. Its heart has been ripped from its sleeve and stamped down in the gutter, yet it persists in beating. Here’s an example: Detective Lee has been investigating a string of corpses found in the city of Purgatory. On his beat, Lee encounters a familiar prostitute, Glitter.

As a detective, it was good practice to keep on amicable terms with working girls. Their information had helped him crack dozens of cases. She tapped on his window and he rolled it down.

….

“You stay put, if you’re here when I get back there’s a twenty in it for ya.” He reached over her lap and took his handgun from the glovebox, placing it in the holster under his jacket.

“Why not fifty?”

Just like a whore to barter when she’s got nothing to offer.

Lee breaks into a storage unit and discovers medically removed human remains and a message written in vomit: “Dinner is served.” When he returns to his patrol car, Glitter is gone. He gets in and cries: “Tears were sparse. Instead he cried with his throat.”

Townsend develops a tone and atmosphere that’s distant without being cold. This objectivity bleeds into the subject matter, taking what might otherwise be described as magical realism into a realm in which genre is obliterated. Distinctions between the real and unreal collapse. One character is named “the skeleton man,” another “Laz[arus],” and the city, “Purgatory.” The narrative threads stitching the scenes together are so fine that the reader stops questioning whether to take it all as symbol, nightmare, or farce. The correct answer is something that includes all three.

With hypnotizing prose, Townsend lulls the reader into a dreamy acceptance of the absurd and the violent. Gutters filled with rain-soaked trash. Fluorescent offices barren of dust. Cheap sex crude in its lust. Serial murders associated with obscure rituals. Seemingly disparate scenes and episodes begin to fit a pattern, a bastard illogic where no action is refused. One way to read this is as the reflection of a psychological interior. The skeleton man burns his birth certificate and employee badge and gets back on dope: “Disappearing. Disappeared. He was no more. He did not exist. He was no longer an employee. What was he? Was he still a human being? Was he now, for the first time, an individual?”

In the very next chapter, Belinda Daisy, involved in a complicated, drug-fueled love triangle, is having a threesome with her husband, John, and her friend Diana. Lost in a jealous thought during anilingus, she wonders:

All this nonsense about John and his slut was distracting her from the job at mouth. She was trying to learn something new about her friend and thus, herself. Reading her with her tongue. Tracing the grooves as if they were a defunct civilization’s version of Braille.

Employment as Identification. The Self cast into high relief to Others. Existence as Pleasure. These resonances build up with zero pretension, forming a glorious Fibonacci spiral of meaning that ultimately condenses into a dark star. Purgatory’s rotating storylines don’t jump tracks, but they do play off each other. Earlier in the novel, a psychiatrist yammers on about her theory of anal information. Hence, Belinda’s revelation above: “If you want to know someone inside and out, then you have to start on the inside because what you find there will inform what you find on the outside.”

Pornographic noir, guts and garbage and soul, Purgatory produces a unique high. Townsend combines the acidic misanthropy of Bret Easton Ellis with the pop slapstick of Mark Leyner, sacrificing neither quality for the other. But the novel’s greatest achievement is that, for all its sick laughs and sicker terrors, it never dissolves into nihilism. There’s a big heart leaking from the leaves of this book, and the characters are made more real for their anxieties and agonies. Dante himself couldn’t have made a Purgatory with more charity.

Conor Hultman lives in Oxford, Mississippi.

More Reviews