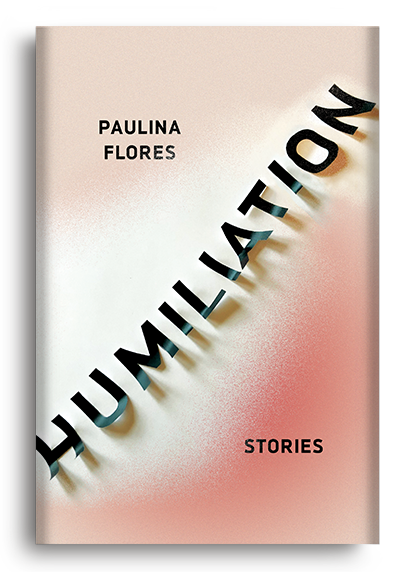

Humiliation: Stories by Paulina Flores

Reviews

By Ross Nervig

Is there a more maligned figure than the father in contemporary fiction? My wife and I debate this in endless circles. She thinks mothers get the worse treatment, but I argue otherwise. For every Atticus Finch, there are ten Jack Torrences (The Shining) and Glen Waddells (Bastard Out of Carolina). My theory plays out in Paulina Flores’s debut collection, Humiliation, across nine stories set in Chile. In some of these stories, the sorry state of unemployment of the father frames the narrative; at other times throughout the collection it is the locus of the conflict. In still other stories, it is the father’s absence that flavors the struggle of the protagonist. And if not an absence then a sort of disgraced presence. It is a father’s humiliation that gives this collection its title. Fathers and their shortcomings provide the canvas on which Flores depicts the struggles of women and children—characters who make it “clear how superfluous fathers” are, as one narrator states.

The big arterial theme running through this collection is reckoning with the indelible mark poverty leaves on one’s childhood. In Humiliation’s opening pages, an unemployed father—the first of many—rushes through a hot Santiago day with his two young daughters toward a modeling opportunity that he and his eldest daughter both misread. In the collection’s best story, “Talcahuano,” four penniless teenagers who while away their boredom translating lyrics of Morrisey devise a plan to steal a local church’s musical instruments to form a band, distracting the story’s main character from realizing that his jobless father is in trouble. Flores has a knack for writing from the point of view of children. The children of her stories find themselves at pain points in their young lives that often break their illusions about the way of the world. A daughter witnessing the financial humiliation of her father. A son discovering his father (jobless and depressed) after a suicide attempt. A young girl spying on her dad in bed with the nanny. Another realizing that her dad is in prison for something far worse than shoplifting.

It is fitting that the Spanish-language edition of Flores’s collection won the Roberto Bolaño Prize. She and Bolaño both render the everyday (often abject) with steady and serviceable sentences while occasionally employing a phrase that crackles and fizzes with the poetic. The plots are often psychological in nature with endings that aim for a heady ambiguity. This can work to startling effect, as in the book’s final near-novella, “Lucky Me,” a languidly unraveling double narrative shared between a loner inviting a couple to use her roommate’s bed for sex and a young girl whose best friend’s mother becomes her family’s housekeeper and nanny. Other times, it does not work so well. A few stories prompted me to ask upon finishing: “What did I miss?” As in the story “Teresa,” in which a young woman is seduced by a man who might be using his own little daughter to maybe bait potential lovers into sleeping with him or maybe not. Likewise, there is a monotony to the prose caused by the narrators’ voices being too alike in their tones and patterns of emotional reaction. Written almost entirely in the first person, these stories feature characters that vary in age, sex, and situation, but all the narrators come off as remarkably similar (a flaw of Bolaño’s short story collections, as well).

Alongside the Bolaño prize, Flores has won the Circle of Art Critics Prize, the Municipal Literature Prize, and was selected as one of the ten best books of the year by the newspaper El País. “Every once in a while, one encounters a new voice and thinks: they will last . . .” wrote Javier Rodriguez Marcos of Flores in El País. Humiliation, translated by Megan McDowell, marks Flores’s arrival and signals her vast potential for portraying the struggles between classes and genders, the intense experience of losing innocence, and the sacrifices and horrendous mistakes people make when they are struggling to parent in a harsh world. I look forward to a novel by this new author exploring these themes in greater depth where a single sustained voice would enhance the effect.

Ross Nervig is a writer living in Nova Scotia. From 2012–2017, he served as a founding member of Revolver—a literary arts collective based in St. Paul, Minnesota. His work has appeared in Kenyon Review, Bluestem Journal, Bayou Magazine, Southwest Review, and Huffington Post. He is currently an MFA candidate in fiction at the University of New Orleans. In 2018 he received the UNO Creative Writing Workshop’s Ernest and Shirley Svenson Award for Fiction.

More Reviews