Notes from the Bathroom Stalls of Our Hearts

Reviews

By Conor Hultman

Jon Berger doesn’t waste your time, so neither will I. Goon Dog (Gob Pile Press) is the daisy growing out of the manure that is the American idiom.

Berger writes a story in a way that strikes to its center. Here’s how. First, he sets up some characters who are quick and bright and different enough from each other to tell apart. Then he spins them like tops. They do a beautiful dance; in their ellipses, they describe their surroundings. They talk, crash into each other, bounce around, then fall down. By the time it’s all over, you realize the story you just read is a lot like the stories you encounter in your own life. And you realize your life is a lot like other people’s lives. Then you turn the page and Berger sets everything up again.

There’s a lot I admire in these stories, especially their concision. Take these opening lines: “Brianna liked baseball, believed in a god and was in the Army Infantry back when she was a dude”; or “It was the night after Christmas and we split some acid.” Whether the story ends up being two pages or twenty, it’s composed entirely of tight, percussive lines like these. Berger keeps his dialogue short and hews to the real common vernacular. No soliloquies or pontifications, no meandering inner monologue, no front-loaded backstory that dwarfs the action: Berger gives you pure storytelling, the short story burned back to its roots.

Another thing I admire about Goon Dog is how it marries humor and sadness. For example, “Saginaw Man,” which begins “Saginaw Man never lived anywhere.” On its own, this is a chilling, cryptic line about homelessness that’s full of deep meanings that emerge the more you think about it. But then:

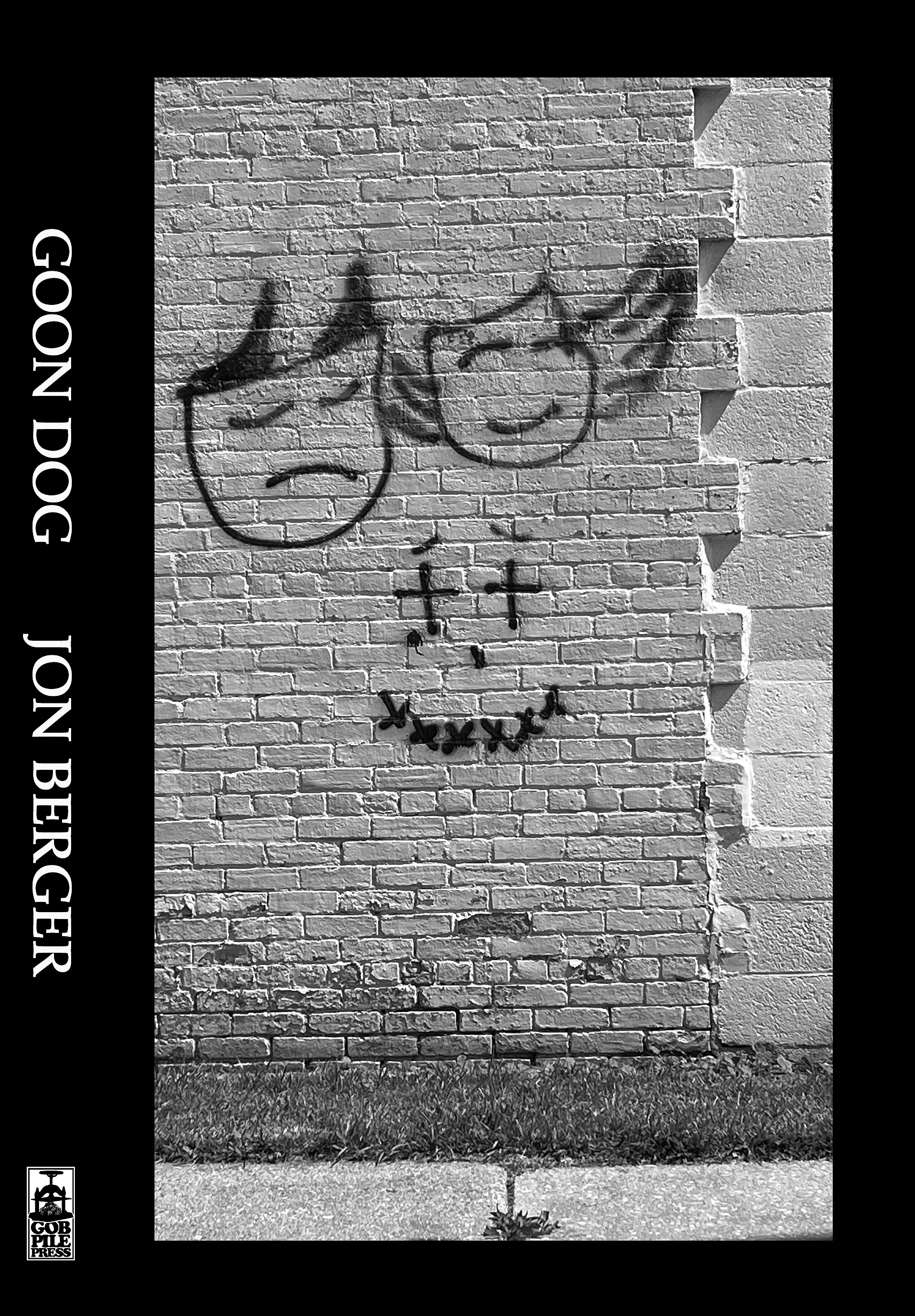

He just hung out at certain places all the time. His favorite certain place to hang out at was the gas station in town. Across the street from the gas station was a vacant lot with a brick wall where someone had graffitied in huge block letters: “SAGINAWESOME.” Saginaw Man liked looking at the graffiti.

The story continues in this tragicomic mode, giving Saginaw Man additional dimension until he becomes a hero, and a character, and a person. Most stories choose among these options for their actors, but Berger juggles all three deftly. So deftly that the ending leaves the reader reactively drawn and quartered:

Saginaw Man was told to put down the plastic spork and stop crying or they’d kill him.

Saginaw Man said, “NO! I AM REALLY PISSED OFF!”

The Police said, “Put the plastic spork down Saginaw Man!”

“I AM SO FUCKING PISSED OFF RIGHT NOW! I AM SO GOD DAMN FUCKING PISSED OFF! WHAT IS WRONG WITH ALL OF YOU! FUCK ALL YOU STUPID ASSHOLES!”

All the cops shot Saginaw Man at the same time. They shot him like 100 times or some fucking bullshit.

Saginaw Man felt the bullets go through him like they were butterflies.

And he fell back on the concrete and died like he didn’t mind the difference.

Is it absurd? Is it brutal? Is it tender? Is it still funny? Berger ushers you through these ambiguities with a reassuring “yes.” No story, not even a single sentence, speaks in a monotone. Another example: “Nothing will remember anything, but the void will know a person was kind to me.” This is the expression of a heart that is hurting but still has its faculties. Too much writing goes for cheap cynicism, an unearned disaffection. Berger knows that it’s harder—and worth more—to hold the line between maudlin and jaded. He understands that a person, their desires, and the litany of things that have been done to them fashions its own kind of short story. And he appreciates that there’s no one feeling the reader should have if they happen to read such a story.

Berger makes this all seem so effortless, too. Goon Dog is full of stories that you could actually read to random people out in the world because they come from out that world. My favorite story is “Special Beam Cannon.” The main character, his cousin, and their friend Joe go out drinking at a bar. They’ve all lived in the same town their whole lives, they all work together, and each one’s mother is dead or dying. But the story doesn’t limit its focus to them. It also ventures into the lives of the other people in the bar. “This dude Frankie was getting evicted from his apartment and started crying”; “The bar owner is a biker cokehead”; etc. Berger manages to make the town, and the party, feel truly populated. Then the story snaps back into focus on the three main characters. Joe bumps into a rich guy “drinking a Red Bull Vodka like a real piece of shit.” A fight breaks out and leads to further developments I won’t spoil here except to say that someone steals a snowmobile. Ultimately, “Special Beam Cannon” is the kind of story you’d hear from your own weird cousin, only distilled to its essence: an Ur-Cousin Story, but told in a way that only Berger can tell it.

Read Goon Dog. These stories are notes scrawled on the bathroom stalls of our hearts.

Conor Hultman lives in Oxford, Mississippi.

More Reviews