Regarding the Matter of Oswald’s Body | A Conversation with Christopher Cantwell

Interviews

By Weldon Pless

Something is rotten in Dallas.

It’s 1981, and the powers that be have decided to exhume the body of Lee Harvey Oswald—a longshot attempt to quiet conspiracy theorists and prove once and for all that the corpse decomposing in the ground is, in fact, the man who shot Kennedy. It’s a twist in the JFK assassination saga so outlandish it’s hard to believe it actually happened. It’s also the perfect starting point for Christopher Cantwell’s Regarding the Matter of Oswald’s Body, a rollicking JFK conspiracy thriller for the post-truth era.

Set in Texas in the days surrounding the assassination in 1963—and bookended by Oswald’s exhumation almost twenty years later—the comic follows four strangers who are recruited by a mysterious agent to help bury the truth about JFK’s murder. It’s an unlikely band of outsiders, each with their own skills—and their own secrets. There’s Shep, a former grocer from Wisconsin peddling himself as a Stetson-wearing, bank-robbing cowboy. Wainwright, a wannabe G-man hiding his sexual identity from the CIA—and his father—in hopes of gaining their approval. Rodrigo, an undocumented immigrant (and former car thief) who sings Dylan covers under the pseudonym Buck Willie. And Rose, a world-weary civil rights activist who also happens to forge checks. And only as they reckon with their own fabricated personas do they attain agency or approach redemption. Part crime noir, part heist thriller, part comedy of errors, and all deeply American, Oswald’s Body concerns itself less with the slippery details of the JFK assassination than with the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves—our own personal mythologies.

It’s also funny as hell. Issue #4, a standout in the series, features a monologue from Lee Harvey Oswald himself that runs nearly cover to cover, as he waxes poetic about his own historical importance. Hilarious, pitiful, and culminating in a crescendo of violence, the issue feels like something straight out of a Tarantino flick.

On a video call, I spoke with Chris about comics, conspiracy, Texas, and more. What follows are edited excerpts from our conversation.

Weldon Pless: Let’s start with Oswald’s body. Why focus on this one sliver of the broader assassination conspiracy?

Christopher Cantwell: I’ve been mildly obsessed with the JFK assassination story for a long time. So when I read the story about Oswald’s body being exhumed, it seemed like a fun thing to tap into. I wanted to keep it contained because it was going to be a miniseries for Boom! Studios. I never really imagined it as an ongoing story. And the assassination feels very contained because you’re really focusing on something like two days and change. A crazy forty-eight hours. Obviously, I have some prologue and epilogue in there, but so much of it is contained.

The exhumation of the body is something that, even for people who are entrenched in the history of the assassination, is more of a side detail. But it’s nuts. They actually dug him up. They drove him back to Parkland where he died—and Kennedy died—and within a few hours, they were like, “Yeah, it’s him.” And then put him back and sealed him up in cement. It’s just bizarre. And it always will be bizarre.

WP: It seems like a perfect metaphor, this exhumation of the body. Every time you rehash the story, it’s like you’re digging up more bodies.

CC: Yeah. You’re kind of exhuming the story of what happened. That was an interesting framing device for me. But I also loved that, on a human level, digging Oswald up didn’t satisfy anybody. Of course. People immediately came out and said, “No, it’s not him. Height differences between the body,” blah, blah, blah. The Kennedy assassination and everything tied up in it defies logic in a way that I think is like a foreshadowing of how things are now, in this kind of post-truth era.

There’s something about conspiracy theories that crave certainty. Even in the face of facts, you deny them. The fear brings you back to the uncertainty, and you just kind of live in that cycle and rinse and repeat, rinse and repeat.

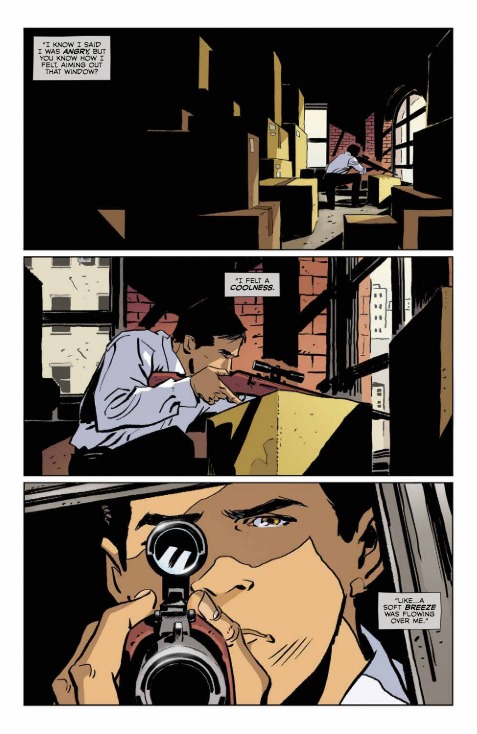

I read a thing years ago—and I don’t know who I’m paraphrasing—but it’s this idea that conspiracy theories are born out of the human mind’s inability to grapple with an event that is truly irrational. And therefore the mind assigns all this meaning after the fact, and builds the structure, and builds the drama, and tells the story. We assign a narrative and go, “No, it wasn’t this crazy thing that was chaos and total luck. I can’t believe he made that shot. It was one in a million and just happened to be in the right window at the right time with the mail-order rifle, and who the fuck is this guy? He killed the leader of the free world in broad daylight. That’s impossible. It’s this.” And then there’s this beautiful, crystalline structure. And you believe it so you can go to sleep at night.

And the funny thing is, people say the conspiracy theory makes you paranoid. But, to me, a conspiracy theory is almost like a security blanket. It anesthetizes you to the chaos and absurdity of the truth, in a way. And I’m not saying it’s all clean-cut, and here’s the Warren Commission and we’re done. That clearly has its own problems. The Warren Commission had its own agenda and assigned its own narrative. And so, at a certain point, the truth isn’t just lost. It’s annihilated.

To me, even though my story is definitely a conspiracy story, it’s really about those four characters and Oswald being totally at the whim of the chaos of reality. In the end, those characters fight so hard to have agency, but they just don’t. That noble effort to stand up against that chaos is what defines them, not the plotting or the master plan. It’s the seat-of-the-pants, try-to-survive-until-the-morning aspect of it that we all actually live with.

WP: It’s really a story about our need to make our own stories. Shep has told himself a story that he’s a cowboy. And you’ve got Rodrigo, an immigrant who’s telling a story to the world that he’s “Buck Willie.” And Wainwright, who’s closeted and forced to tell a story to the world to keep his secret.

CC: Yeah, it’s almost like this idea of everybody clinging to this sense of self, this sense of what they need to be and what they believe themselves to be, in order to get through the day. And the radical move is to let that go. And that’s something that I find I do every day.

I see it everywhere. America has all these opposing stories about itself, and I think there’s this idea that we are the stories we tell about ourselves, and then we are also absolutely not. Those stories are ultimately ephemeral and blow away, and the truth is infinitely more complex and complicated and less succinct. You can be a piece of shit human being who, at one point in your life, I don’t know, saved an old lady from getting hit by a bus. You can be all those things.

WP: We contain multitudes.

CC: Exactly. And America is the same way. And it drives some people crazy. I think it’s driving a good amount of the population crazy at this point, you know? From every walk of life.

And the ’60s were another time when the country was a million different things at once. Then all of a sudden, the President was dead. What a crazy time. And I feel like the most difficult crucibles we go through are when our stories about ourselves and our country are directly challenged. Assailed, in a way. That’s when things get really intense for a person. It’s also when they get really interesting in terms of story.

WP: Why a comic book? Did you ever think about a film?

CC: The pandemic hit in 2020, and the show I was running with my partner, Chris Rogers, was deferred. Everything was put on hold. So I started just pitching different comic book ideas around. I wanted to play with different genres. Oswald’s Body was one I took to Eric Harbor at Boom. It was a crime pitch. I love movies like Blood Simple, and I wanted to write something with that regional Texas element. I grew up in Dallas and wanted to try and channel that into a story. I also wanted it to kind of be this character piece. And he really liked the pitch, so I was able to put that book together.

We brought on Luca Casalunguida—and Giada Marchisio doing the colors—from Italy. It was fun to work with them because they had a foreign perspective on the assassination. It’s not like Luca grew up down the street from me. But he really studied the era and looked at a lot of photographs and did all that research. And he has such a great way of bringing the acting to the characters in his art—a way of capturing that era and the tone of the story, visually.

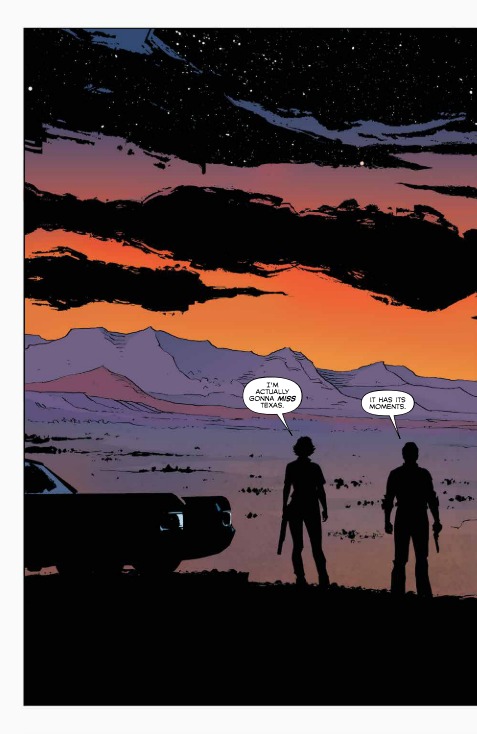

WP: Can you talk more about the Texas aspect? There’s a big spread where everyone’s looking at the sunset and waxing poetic about how they’re going to miss Texas, even after they’ve mostly been rejected by it. And there are other moments along the way, like the Alamo stand-off sequence. It feels very Texas, but also it’s deflating the myths a little bit.

CC: Yeah. I wanted to do that. I grew up as a transplant. I moved to Texas when I was nine weeks old, but I was born in Chicago. My whole family was from there. My mom’s from Germany. So I’ve always felt connected to Texas, but also apart from it. I have relatives and friends who are like ninth-generation: they can trace their families back to the War of Independence and through the Civil War. But the most interesting people to me from Texas are the ones who question their relationship to it. Not even question—examine it. When you live in Texas, parts of it are special, and parts of it drive you crazy and make you frustrated and angry. When I was eighteen, I couldn’t wait to leave. And I’ve spent the last twenty-two years fondly looking back on it. I love visiting. I love going to certain parts of the state, seeing my friends and feeling connected to those places. And I wanted the characters in Oswald’s Body to all have that experience of being at once Texan and also apart from it—and a little resentful because of that.

You have Shep, who’s from Wisconsin: he just feels like he never fits in. You know, Wainwright is a kid who grows up in a really rich area of Dallas yet doesn’t fit in. Like you said, he’s closeted; he’s trying to make his dad happy. They’re all trying to be something and also fighting against things they’re not. Rose is a Black woman living in South Dallas during the Civil Rights era, and that stuff she talks about in the first issue—that actually happened. They got Martin Luther King Jr. down there in 1963, and shortly after somebody did burn a cross in a Holocaust survivor’s front lawn. That’s real. And that’s Dallas, right? It’s like, we got Dr. King to come speak here, and people were vocal, and they were a part of it, and there was this forward momentum. And then watch us take this insane, stupid step backward right after the fact. To me, that really sums up Texas’s audacity in both directions.

And I love that spread because I wanted to present the panoramas of the state. I wanted some of those vistas. It’s almost like those characters are feeling the same thing I felt when I left: they might know they’re on their way out, so they start to miss it. It’s the same thing when Shep gives away his identity. Right after that, he does the most cowboy thing he does in the whole book: a quick draw. It’s like, you only get it if you let go— that kind of idea. And Texas is tied up in that.

WP: Speaking of the quick draw, the first thing that struck me about Oswald’s Body was the number of genre tropes it goes through in the first five pages. We open on a gruesome corpse among tombstones in a graveyard, then you pull out to this cowboy silhouette, then cut to a bank robbery. And pretty soon we’re putting together a team for a heist. Were you thinking about genre as you were working on those pages?

CC: I wanted the book to be gritty. I wanted it to be in that comic crime genre. I wanted something that really could sit on that shelf. I thought it was also cool to open with Oswald’s actual body in the coffin because he is, through the literal luck of the draw, indelible now. Eternal, for better or worse. He’s a mugshot. And so there’s a shitty rockstar quality to this motherfucker. I think I also wanted to start with his worm-eaten body in a coffin, like, “This is what he actually got, folks.”

By the way, there are photos of the exhumation. I wouldn’t look those up. They’re not pleasant. But they do kind of ring your bell, where you realize death is death—however glorified, however dramatized, however crystallized by our perceptions, death is death. And I think I wanted to put the stink of death on this story from the moment it started.

I also wanted to set up some tropes and then knock them down. So you start with Shep as a bank robber, then you quickly realize he’s a terrible one. You’re seeing him try to live the legend, and it sucks. And the getting-the-band-together stuff in the first issue—that’s always such a tough thing to write. But it felt like we could do it while having fun and setting a tone for this world. I wanted to meet these people; I wanted to see their facades and what was underneath them. That way, when we stitch them together, we know what they have to lose.

WP: Speaking of Oswald’s legacy, I absolutely loved the sequence where Lee Harvey Oswald, in life, will not shut the hell up.

CC: He’s diseased with his own story. He’s insufferable. I wanted to do an issue that was mostly a monologue by him. I thought that would be fun to write. I also thought it would be fun to have him say things where you’re like, “he’s probably right,” but also, “what an asshole.” That’s the closest I think I tried to get to history because I have no love for that person. I think he needed help and was never going to get it. But he believed he was a lot more than he was, and he couldn’t reckon with the fact that he was small.

And that’s a very poisonous thing, especially in America. People cannot reckon with the fact that they are small. They buy so much into that overly simplistic version of the American dream: the rugged individualism and American ingenuity thing that gets peddled. Oswald wanted to prove to everyone that he was a big deal. But he didn’t prove anything to anyone. He didn’t prove shit—except that you can get lucky with your aim once in a while.

WP: It’s so interesting. In a way, each of your characters has to give up the story they’ve been telling themselves and come to terms with their place in the world. But Oswald is the exact opposite. He’s so drunk on the idea that he’s important, in an almost cosmic sense, that he’ll never accept that he’s a cog in a machine.

CC: He’s poisoned by a sense of self with a capital S, which can be an unfortunate side effect of American identity. There’s so many beautiful things about American identity and the American dream. But one of the side effects can be the Ayn Rand shit that can lead you to take shots at people. And it can really destroy you and destroy others.

WP: Out of curiosity: I read the first issue of your newest comic, Briar, and I see some similarities between it and Oswald’s Body. Can you tell us any more about Briar?

CC: Yeah! A lot of the same stuff we’re talking about, especially the sense of self. Briar Rose, of Sleeping Beauty fame and lore, is somebody who has been told she’s something her whole life. Royalty. Magically endowed. Doomed to some kind of fate if she’s not careful—this literal fairy tale she’s been told. And her whole struggle in Briar will be her wrestling with who she’s been told she is versus what the world actually is. Or who she might actually be or not be. If she can let that fairy-tale version of herself go, that’s where the real strength might lie.

Weldon Pless is a writer and filmmaker from Birmingham, Alabama. His play “Last Call” appeared in The Best American Short Plays 2013-2014, and his film Ricochet won Best Short Film at the 2019 Hill Country Film Festival. He lives in Los Angeles with his wife and two sons.

More Interviews