Slow Your Heart, Hold Your Breath

Reviews

By Mila Jaroniec

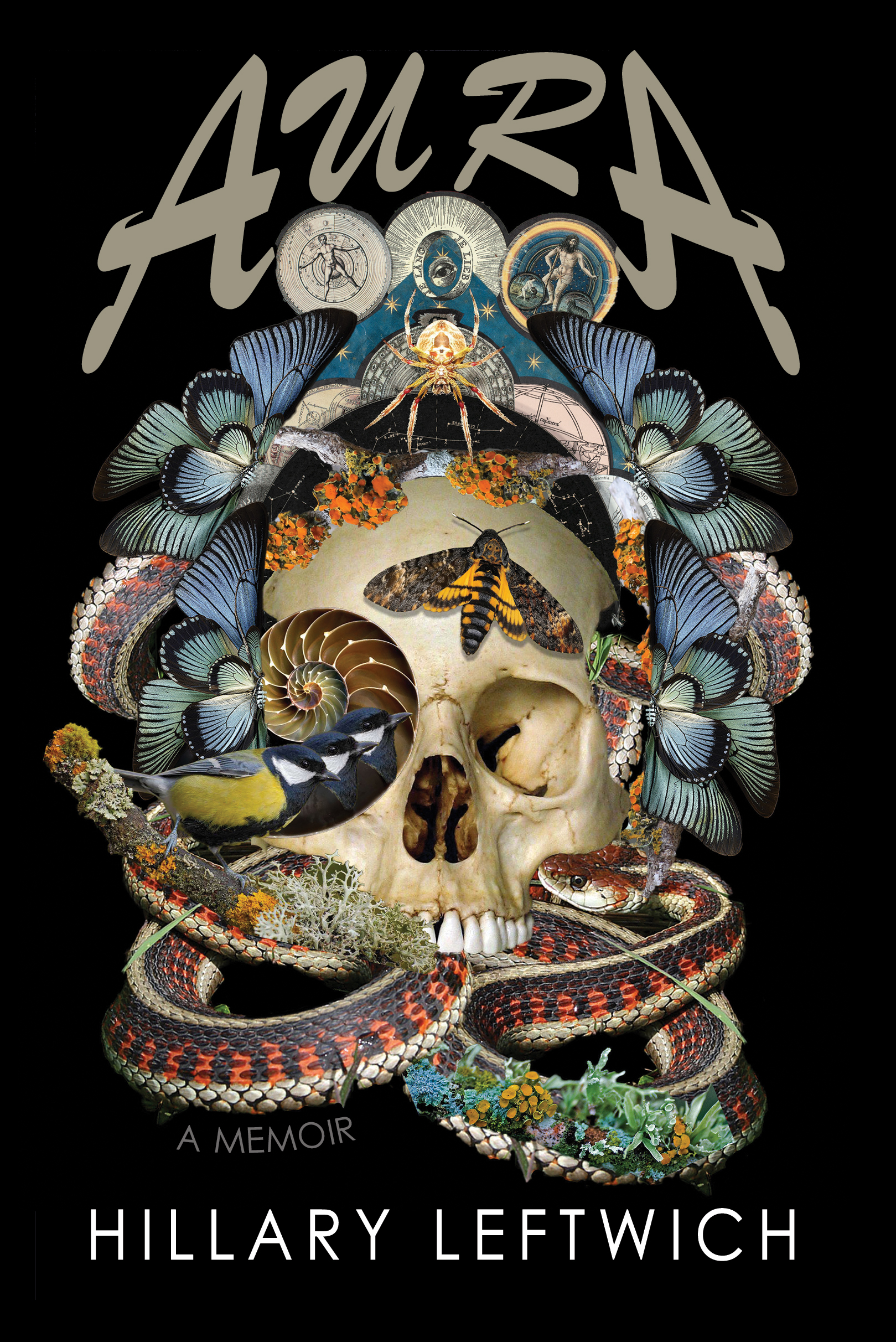

Although I don’t actively avoid horror, I’m definitely one of those old-school Slavic mothers who think that real life is horrifying enough without any additional horror content. I’ve always been more frightened by the things human beings have the capacity to do to each other than by demons and monsters. Child abuse, animal cruelty: these are the things that keep me up at night, wondering where they come from, how a person can harbor that much rotten hate, and how such a person can be loved. Enter Aura (Future Tense Books, 2022) by Hillary Leftwich, a piercing, gorgeous memoir heavy with life and heart and the will to survive. This book is devastating, exacting, and beautifully rendered without ornament. It’s also terrifying because of how lived it is—how absolutely true.

Aura tells the coming-of-age—and subsequent surviving-of-age—story of Hillary Leftwich, a young witch, mother, and survivor of domestic abuse and cult-like Christian doctrine, of patriarchy and its sharp brambles. The book, written for her epileptic son, is an explanation, excavation, and incantation, a document of a single mother’s fierce protection of her child’s life against impossible odds and of the indefatigable spirit it requires. Beyond that, Aura documents the artist’s way and the witch’s way. It speaks of writing as medicine and of witchcraft as life force, and both as shields against a predatory world that so often drops us into shark-infested waters, naked and smelling of blood.

The book’s short chapters, which begin in Hillary’s childhood and continue throughout her young adulthood and a series of ill-fated relationships with various types of abusive and inadequate men, are spliced with mementos from her son’s early life, medical records, legal documents, photographs, handprints, footprints, drawings, and spells, as well as letters from editors at literary magazines to whom she submits her work. Although the narrator has been writing all her life, she’s always found being a Writer somehow unpalatable. The first time Hillary sees a writer live, it’s a hard-living, bitter cliché of a man who thinks he was owed more than he got from the creative establishment, and the result is desperate and embarrassing. Hillary thinks: If this is a writer, I never want to become one. But she keeps writing because it’s the only thing that belongs to her alone, because it feels like salvation, because her spirit requires it. An English professor she meets while working at a bar reads her early pages and tells her to keep writing—to never sell her words short, because they’re worth something. This encouragement is the talisman she keeps close to her heart as the rejections roll in. Each time they are kinder. Each time the editors are more impressed. Eventually, she receives her first acceptance.

More than a concept can do for a work of nonfiction, Aura’s unifying elements—spellcraft, memory, earth magick—serve to make everything in the book of the book. Which is to say, they belong here and nowhere else. Beyond the magick, there is also Magic: that all-surrounding supernatural element that we can’t reach out and touch, that is given voice in the descriptions of cold, green water, of loving animals and rocks and wind, of the ancient intelligence coursing throughout and underneath all life. Sometimes the spells work, and sometimes they don’t, which is equally true of prayer. As Michelle Tea notes in Modern Tarot, practicing magic is like spiritual crafting. Who knows if any of it holds water. But if it makes us feel better, does it matter?

But the most striking aspect of Aura might be its depictions of living with abuse. The popular image of the abused woman is a woman who is completely alone, out on an island. But the reality is often something very different. Hillary has people around her. Parents. A brother and sister, somewhere, and friends. Why isn’t anyone doing anything to help? Why do they just let this happen? But that’s the nature of the beast: an abuser will psychologically isolate you, make you feel ashamed and responsible, scared to reach out. You’ll think it’s all your fault; you’ll think you’ve made your bed so you should lie in it, that people will judge you if you share. Sometimes it’s even worse if you do share. After escaping with her son to a women’s shelter and spending some time there, Hillary does, eventually, go back to his father. It’s a horrifying episode, but it’s emblematic of what so many people get wrong about domestic abuse: the police often do nothing. Trying to get out of an abusive relationship with limited resources, no money, anything save an absolute identity wipe and witness protection program, often exposes the abused to much worse consequences.

Publishers today gravitate toward memoir plus, which rests on the idea that a memoir has to be about something else too in order to engage the reader. The thinking behind this trend is that individual stories are not compelling enough to stand on their own. There needs to be a gimmick, a hook, something to draw the reader in and keep them turning pages. That something else can be rewarding. Traditional memoirs, if badly written, can veer into the depressingly formulaic, following a narrative arc that bends toward redemption. We know that the author has made it out; that’s why there’s a memoir. But Aura does not follow that formula. As late as the final ten pages, I wasn’t sure if Hillary and her son were out of the woods just yet. I could still feel a lurking threat, the possibility of more violence, the uncertainty that is life in those pages. Nothing was rationalized or moralized. No one was absolved. The narrator drops no conventional breadcrumbs. The journey from the dark to the darker to the light is its own propulsive narrative: our human attempts at survival, held together by wishes and magic.

Aura is an incandescent, gripping, and wholly original work of lyrical nonfiction that encapsulates the fierceness of a mother’s love. It’s a book that’s certain to be instructive and inspiring for writers working within the memoir genre. But beyond that, Aura is a salve, a gift for anyone who’s stared down the darkness, stepped into its open mouth, and taken a deep breath.

Mila Jaroniec is the author of two novels, including Plastic Vodka Bottle Sleepover (Split Lip Press). Her work has appeared in Playgirl, Playboy, Joyland, Ninth Letter, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, PANK, Hobart, The Millions, NYLON and Teen Vogue, among others. She earned her MFA from The New School and teaches writing at Catapult.

More Reviews