Some Movies Are Made Timeless | Scout Tafoya on John Ford

Reviews

By William Boyle

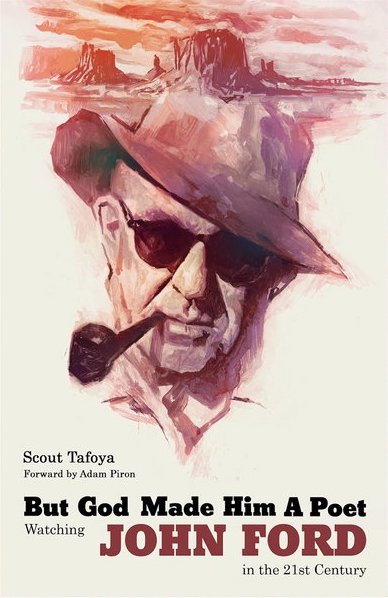

In But God Made Him a Poet: Watching John Ford in the 21st Century, Scout Tafoya tackles famed director John Ford’s entire filmography. He discusses the films in chronological order, offering short introductions to each chapter of Ford’s long and varied career. In relatively short entries, he manages to frame each film through the lens of cinema history (what came before and what came after, who influenced Ford and who was influenced by Ford), while reckoning with how to see and read Ford’s complicated art in the present moment. In Tafoya’s estimation, the director is “American cinema’s greatest poet.”

Late in the book, Tafoya writes that “[nothing] Ford ever did was uncomplicated” and that it’s “our job to live with the contradictions.” I thought I’d skip around, but the book is a totally immersive page-turner. I tore through it in several sittings, only stopping to punctuate my reading with screenings of Ford’s films. Tafoya’s writing, marked by long parentheticals and asides overloaded with both joy and information, hums with energy. His enthusiasm is contagious. Esteemed film critic Molly Haskell calls Tafoya’s approach “rambunctious, lyrical, conversational, [and] deeply knowledgeable.” If you’ve ever watched one of Tafoya’s excellent video essays (if not, check out the archive of his ongoing series, “The Unloved,” at RogerEbert.com), you can hear his voice here. He can’t help writing like he’s whispering revelations to you.

Like most cinephiles, I’ve seen many John Ford films. I generally consider myself a fan (especially of revered works like My Darling Clementine and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance), but I’d never gone truly deep. In his introduction, Tafoya discusses the point of his project: to do a study of Ford’s films “specifically from the vantage point of this moment in time.” He goes on to explain that he’s “[attempting] to look at the necessary and thorny work of unpacking a conflicting and frustrating political worldview as reflected in movies made by one man across six decades that also saw two World Wars and ten presidents.”

In part one, Tafoya reveals that he’s troubled by the current climate, which seeks to avoid or dismiss difficult art. In fact, he finds this stance disingenuous. Why (he asks) do we desire movies that “answer questions with no complication” when so many things are getting worse every day? Ford’s films often offered beauty and ugliness in equal measures. Tafoya writes: “To study John Ford, to know John Ford, is to keep at least two ideas in your head at once because they happen to be about the same man. What worries me just enough is we’re losing the will to do that.” He continues: “Looking back at a culture and only seeing perfect art with perfect values won’t teach us anything. America never had a moment where it rose to good, let alone perfect. Why shouldn’t our movies look headlong into the abyss of violence? That’s honest, isn’t it? If we lose our picture of the past, we’ll paint it again with new lies.” Whatever Ford was doing, for better and worse, Tafoya posits, the “same splendor touches everything.”

In examining Ford’s silent films, Tafoya refers to the director’s searching nature: how he left Maine, discovered movies, and began telling stories of the wide world. (“The melancholy of never finding home,” Tafoya writes, “never feeling at home would dog Ford his whole life.”) Although many are lost, Ford’s earliest extant films pose the question, “What does the audience want to see, and how do they want it shown to them?” He was, along with other important filmmakers of the late 1910s and early 1920s, creating the language of cinema. It was a long period of learning—Ford was stealing (often from his hero, F.W. Murnau), inventing, and exploring his obsessions. As Tafoya notes, “Observation and the way in which people fuse with their surroundings and become one with us in the audience transfixed him.” In one of my favorite early entries in the book, on 1923’s Cameo Kirby, Tafoya writes: “Water becomes a conduit for all [Ford’s] technical ideas—a young woman (a still unformed Jean Arthur making her debut) is daydreaming while stirring a puddle with a stick and when it clears there’s the reflection of her unwanted suitor looking back at her, and Gilbert will later spy Gertrude Olmstead, the object of his affection, in a well—because it’s the ephemeral that interests Ford.” At this point in his young career, Ford had “already slant drilled [D.W.] Griffith’s historicity and here is inventing Godard, Renoir, Stanley Kubrick (the duels!), John Huston, and stealing a march on everyone from Clarence Brown to King Vidor . . . One hundred years later, cinema is still in a puddle, reflecting the world Ford created.”

Next, Tafoya traces Ford’s emergence as a titan of cinema during the sound era. “As Ford aged into a state of permanently bent bitterness,” Tafoya argues, “he began to paint his greatest works about the men he could never be.” Yet the films of this period still rely on “the projections of a hopeful man.” Throughout the 1930s, Ford develops his ability to portray places that are “alive with poetry and gritty humanity.” For many of us (and as is the case with Ford’s silent pictures), his films from the early 1930s will be ones we’ve heard of but not seen—Arrowsmith, Air Mail, Flesh (the movie that’s being made in the Coen Brothers’ Barton Fink), Pilgrimage, Doctor Bull, The Lost Patrol, and Judge Priest, to name just a handful. But Tafoya does a fantastic job of making even Ford’s lesser-known work seem essential to a fuller understanding of the man and artist.

What emerges from these two chapters—and the first quarter of his filmography—is Ford’s range. He is more than a director of complicated Westerns. As his earlier films attest, he’s interested in comedy, action, war, romance, and tragedy. He’s also willing to follow stories wherever they lead him. The latter half of the 1930s find Ford making some of his best films of the decade. The Whole Town’s Talking and The Informer are the only two I’d previously seen, and they’re excellent. Tafoya’s entry on The Hurricane (1937) drove me to seek it out immediately, and I wasn’t let down.

Through 1938, Tafoya says, Ford was simply a director, “all too human, all too given to whims and unquestioning devotion to the pages of whatever script was in his hand.” But with the glorious Stagecoach a year later, he transformed into the John Ford that we all know: a director of “undeniable greatness” and “[a] man with such love and such hate in the same heartbeat, in the same blood.” Tafoya’s entry on Stagecoach is rich and enlightening. He notes that every Western afterward was made in its reflection and meaningfully discusses the film’s concern with “the question of finding a moral bedrock in the desert.” Stagecoach is a film that has “every last ounce of America in its frames.” It’s also the start of a significant stretch of iconic pictures from Ford (with an occasional misfire mixed in). Young Mr. Lincoln, also from 1939, is one of my personal favorites, and then there’s Drums Along the Mohawk, The Grapes of Wrath, The Long Voyage Home, and How Green Was My Valley, the film that beat out Citizen Kane for Best Picture at the 14th Academy Awards (Ford also won Best Director over Orson Welles).

Still, although we’re almost twenty-five years into Ford’s career, we’ve barely scratched the surface. 1941-1945 finds Ford making films to aid in the war effort, as well as the stirring and extraordinary They Were Expendable, and then another period of focused brilliance follows. In 1946, My Darling Clementine (perhaps my favorite Ford picture) is released. A retelling of the legend of Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday starring Henry Fonda and Victor Mature, it’s a film where, in Tafoya’s words, “[every] pack of silhouettes in barrooms feels ancient and immortal.” Tafoya concludes that “[some] movies are made timeless.” Of Ford’s underrated The Fugitive (an adaptation of Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory) from 1947, Tafoya writes that “[light] has never looked so much like god’s own cigarette.” Other standout films (and entries) from this period include the Cavalry Trilogy (Fort Apache, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, and Rio Grande), as well as Wagon Master (Tafoya’s favorite—I’m ashamed to say I haven’t seen it, though I just picked up the Warner Archive Blu-ray) and the fable-like The Quiet Man with John Wayne and the ethereal Maureen O’Hara (Ford’s career is threaded with complicated films about his ancestral homeland of Ireland).

Tafoya identifies the bulk of Ford’s work in the 1950s as indicative of his late style, the beginning of the end for him. There are some interesting films here, no doubt, several of which I haven’t seen, and even some of Ford’s TV work looks appealing (I have Rookie of the Year queued up as I type this), but the entry on The Searchers is rightfully this chapter’s centerpiece. It is, of course, Ford’s most well-known film and one of his most complex and nuanced. “The key thing The Searchers gave me as a young moviegoer was the sense of time and distance,” Tafoya writes. I didn’t anticipate crying during a three-plus page reckoning with The Searchers, but, as Tafoya remembers a trip with his father (the great crime writer Dennis Tafoya) to Monument Valley, just “a guy and the kid he raised to see the world through the movies” haunting Ford’s “barren deserts,” I was blindsided by emotion. This entry speaks to one of Tafoya’s greatest strengths: making film criticism feel so personal and immediate. Movies are personal. Our lives are inextricably tangled up in what we’ve seen and how we’ve connected to what we’ve seen; our memories are influenced by these images; our hearts have been shaped by these tones and atmospheres that have taught us how to see.

Late-era Ford is a grab bag. He attempts to atone (not always successfully) for some of his greatest sins in films like Cheyenne Autumn. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, which finds Ford facing down his mortality, is an undisputed masterpiece. Tafoya does it justice, focusing in on the effectiveness and necessity of the film’s ending. Donovan’s Reef is a film I haven’t yet seen, but Tafoya’s entry has me anxious to watch it. Similarly, 7 Women, the last film of Ford’s released during his lifetime, was one I hadn’t seen, but Tafoya’s discussion of it drove me to find it immediately. It was an absolute revelation. I think Anne Bancroft’s one of the greatest geniuses ever, so I’m especially surprised with myself for not having watched it before. Tafoya identifies her Dr. Cartwright as his favorite of Ford’s heroes. I agree. Bancroft, Tafoya writes, is “maybe more John Wayne than John Wayne.” He goes on: “She struts into the film with sexual certainty and no patience for god . . . She smokes like a chimney, constantly bringing up the specter of sensuality. She wears trousers and claims she’s better than any male doctor they could have found. She’s a reckoning on two legs.”

Perhaps my favorite section of the book is the final chapter, in which Tafoya traces Ford’s influence and impact through the latter half of the twentieth century and the early part of the twenty-first. Without Ford, he suggests, much of the last fifty-plus years of filmmaking is unthinkable. In short, even filmmakers who might not be directly influenced by Ford are infused with his spirit and sense of style secondhand through directors like Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Clint Eastwood, and Francis Ford Coppola. It’s a substantial chapter that draws lines from Ford to his obvious disciples. It also investigates his relationship with and influence on a wide range of directors, including Sam Peckinpah, David Lean, David Fincher, David Lynch (who portrayed Ford in Spielberg’s The Fabelmans), Walter Hill, John Sayles, Spike Lee, James Gray, Terence Davies, Michael Mann, Charles Burnett, the Coen Brothers, Eagle Pennell, and Jane Campion, some of whom wear Ford’s influence proudly—if defiantly. Tafoya seems to map every tributary sprouting from the gushing river that is the body of Ford’s work. It’s an illuminating and overwhelming (in a good way) chapter that sent me scrambling to take note of the films I haven’t seen and revisit many others through a Fordian lens. Among the most striking observations in this chapter is Tafoya’s assertion that David Milch and Daniel Minahan’s Deadwood: The Movie has “one of the most faithful Ford structures of any modern film,” which helps reframe it not as the film folks wanted it to be but rather the film it is: a reckoning with time and mortality and regret, a sundown gathering of old friends.

In the end, Tafoya’s book will make readers—as it did me—return to Ford’s films, watch the ones they haven’t watched, and revisit the ones they have. It will also inspire them to engage with Ford’s thorniness in meaningful and messy ways. Tafoya concludes: “John Ford may not be the most important director in America, but there would be no America to regard, to contemplate, to imagine, to see without him. Not the one we imagine, not the one we had to reimagine, not the one we still have yet to build out of stories not yet told and images undreamt.” But God Made Him a Poet: Watching John Ford in the 21st Century is a profound work of film scholarship—accessible, concise, and moving—and it’s essential reading for cinephiles and casual film fans, especially those interested in grappling with complicated art.

William Boyle is the author of the novels Gravesend, The Lonely Witness, A Friend Is a Gift You Give Yourself, City of Margins, and Shoot the Moonlight Out. His novella Everything Is Broken was published in Southwest Review Volume 104, numbers 1–4. His website is williammichaelboyle.com.

More Reviews