Family Matters: On Natalia Ginzburg

Reviews

By Wilson McBee

About halfway through The Dry Heart, one of two books by the Italian writer Natalia Ginzburg recently released by New Directions, the protagonist and narrator prepares to feed her baby daughter while her cousin Francesca looks on:

“What a lot of fuss,” said Francesca as she saw me boiling a spoon. “And when she’s older she’ll just be a pain in the neck the way I am to my mother. Families are a stupid invention. No marriage for me, thank you!”

For some, Francesca’s point of view is easy to understand—especially if you think about how effective the conventional family unit can be at keeping people stuck in cycles of abuse and neglect. But as far as the narrative arts go, it’s hard to argue there’s ever been a better “invention” for capturing the triumphs, contradictions, and tragedies of everyday humanity than the family. One only has to think of King Lear, Tolstoy, The Sopranos. A master at the family drama herself, Ginzburg could have been winking at her own artistic tendencies when she included the above bit of dialogue.

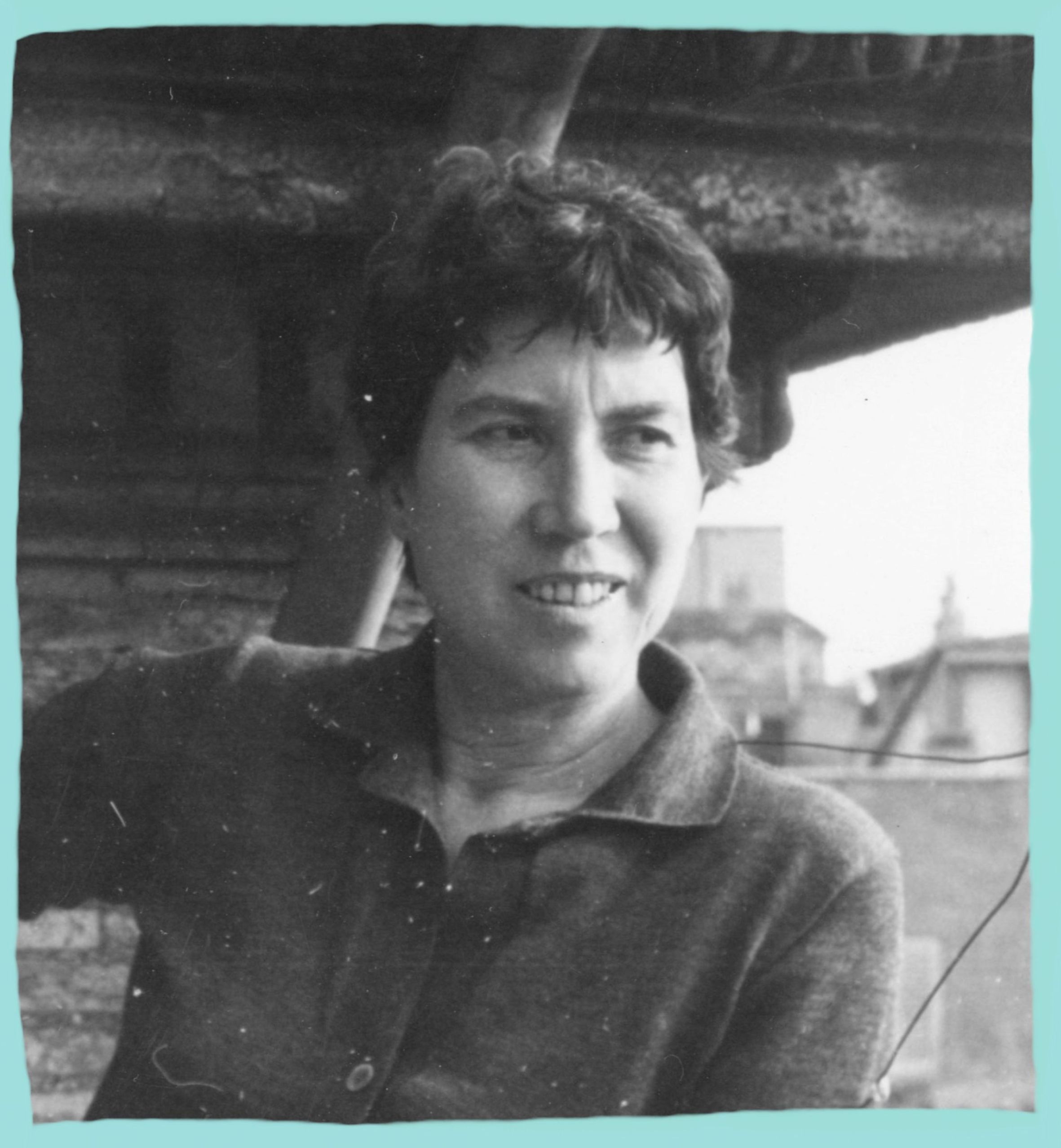

Ginzburg, who died in 1991, produced plays, fiction, and memoir across a long career, and while much of her work has been translated into English, her books aren’t always easy to find, and therefore New Directions deserves kudos for bringing her to a new audience. (Credit also to New York Review Books, who brought out a new edition of Ginzburg’s novel Family Lexicon in 2017.) In addition to The Dry Heart, a novella presented in its original English translation, there’s a new English translation, by Minna Zallman Proctor, of the epistolary novel Happiness, as Such. Both books exemplify Ginzburg’s command of familial dynamics, bone-dry comedy, and her severe, if not quite cynical, view of the world.

The first few pages of a Ginzburg book can feel like arriving at a family reunion where you don’t know anyone. Names, affairs, and feuds come flying at you one after the other, and keeping track of everyone and how they’re related can be tricky. But linger a little, and soon enough you feel like you’re another member of the clan. Happiness, as Such begins with a letter from forty-three-year old Adriana, recently moved to a home in the countryside near Rome, to her adult son, Michele, who still lives in the city. Adriana discusses two events that will figure prominently in the book: the illness of Michele’s father, from whom Adriana is estranged (although they still see each other regularly—partners who break up while remaining heavily involved in each other’s life appear often in Ginzburg), and her meeting with a young mother named Mara, whose baby may or may not be Michele’s. Soon the father dies, and Michele leaves for London, likely to escape reprisals for his involvement in anti-fascist politics, although he never gives his exact reasons for going away. The rest of the book tracks the effect of these dual absences on Adriana, Mara, Michele’s friend Osvaldo, and Michele’s sisters Angelica and Viola. As Mara leads an increasingly tenuous existence as an impoverished single mother, and Adriana attempts to hold herself together, both cling to Michele in their letters as a source of potential support and hope. But the correspondence is one-sided, and Michele continually fails to deserve their affection. Standing in Michele’s stead is Osvaldo, who visits Adriana daily and gives financial help to Mara. Perhaps not coincidentally, the female characters in the novel muse on more than one occasion that Osvaldo is probably gay. Although Osvalda is also separated from his wife, there is little evidence elsewhere in the text to support these suppositions. It’s as if the women find his compassion, faithfulness, and generosity suspiciously unmasculine.

The first few pages of a Ginzburg book can feel like arriving at a family reunion where you don’t know anyone. Names, affairs, and feuds come flying at you one after the other, and keeping track of everyone and how they’re related can be tricky. But linger a little, and soon enough you feel like you’re another member of the clan. Happiness, as Such begins with a letter from forty-three-year old Adriana, recently moved to a home in the countryside near Rome, to her adult son, Michele, who still lives in the city. Adriana discusses two events that will figure prominently in the book: the illness of Michele’s father, from whom Adriana is estranged (although they still see each other regularly—partners who break up while remaining heavily involved in each other’s life appear often in Ginzburg), and her meeting with a young mother named Mara, whose baby may or may not be Michele’s. Soon the father dies, and Michele leaves for London, likely to escape reprisals for his involvement in anti-fascist politics, although he never gives his exact reasons for going away. The rest of the book tracks the effect of these dual absences on Adriana, Mara, Michele’s friend Osvaldo, and Michele’s sisters Angelica and Viola. As Mara leads an increasingly tenuous existence as an impoverished single mother, and Adriana attempts to hold herself together, both cling to Michele in their letters as a source of potential support and hope. But the correspondence is one-sided, and Michele continually fails to deserve their affection. Standing in Michele’s stead is Osvaldo, who visits Adriana daily and gives financial help to Mara. Perhaps not coincidentally, the female characters in the novel muse on more than one occasion that Osvaldo is probably gay. Although Osvalda is also separated from his wife, there is little evidence elsewhere in the text to support these suppositions. It’s as if the women find his compassion, faithfulness, and generosity suspiciously unmasculine.

In her ability to imbue minor lives with grace and significance, Ginzburg could be deemed an antecedent to American writers like Anne Tyler or Frederick Barthelme, often referred to as dirty realists. Happiness, as Such creates quiet poetry from the everyday. Outside of Mara’s more dramatic travails, the back-and-forths mostly concern the quotidian—Michele decides to get married, and needs Angelica to send him some forms; the estate of Michele’s father has to be finalized; Adriana attempts to get a telephone line installed at her home. And yet, lurking in the space between mundane trifles, Ginzburg seems to be saying, is actually the stuff of life. To put it another way, the qualified happiness implied by the title used by New Directions (the book’s title in Italian translates directly to Dear Michele, which has been used in an earlier English translation, as has the puzzling No Way) is maybe the best, if not the only, kind of happiness, even it’s often overlooked in the moment. As Adriana reflects late in the novel, in a letter to Michele, about the last time she saw him:

I remember feeling a big sense of happiness in the middle of arguing and my being angry at you. I knew that my nagging would irritate you but also make you happy. I remember it now as a happy day. It’s unfortunate that we rarely recognize the happy moments while we’re living them.

There’s a morbid sweetness in this revelation—anyone who’s ever lost a parent or other loved one will recognize the desire to go back to even the most uncomfortable moment with the deceased, just to feel their presence one more time. Even as its characters face the challenges of grief, loneliness, and romantic failure, Happiness, as Such testifies to the special value of familial bonds, however strained.

While The Dry Heart also concerns itself with the ups and downs of familial relationships, it is darker in content as well as outlook. The book begins just as its unnamed narrator has shot her husband, Alberto, killing him instantly. Ginzburg then takes us back in time to the moment of the couple’s meeting before proceeding forward to the shocking act of violence. The flashback structure and the narrator’s confessional tone recall the moodiness of a 1940s film noir. And at eighty-three pages, with rapid pacing and a tightly woven plot, The Dry Heart takes about as long to read as it does to watch a feature-length film.

While The Dry Heart also concerns itself with the ups and downs of familial relationships, it is darker in content as well as outlook. The book begins just as its unnamed narrator has shot her husband, Alberto, killing him instantly. Ginzburg then takes us back in time to the moment of the couple’s meeting before proceeding forward to the shocking act of violence. The flashback structure and the narrator’s confessional tone recall the moodiness of a 1940s film noir. And at eighty-three pages, with rapid pacing and a tightly woven plot, The Dry Heart takes about as long to read as it does to watch a feature-length film.

As in most of Ginzburg’s books, family plays a critical role. The narrator has escaped her depressingly dull mother and father, who live in the country, for what she hopes is a more exciting life in the city. Yet she finds another humdrum existence, teaching at a girls’ school and living in a sleepy boarding house. Only Francesca, who is younger but more experienced in the ways of the world, provides anything close to excitement, until the narrator meets Alberto. A sometime attorney, older and independently wealthy, Alberto has his own parental hang-ups. He lives with his elderly mother—one of Ginzburg’s more memorable eccentrics, described, in the excerpt below, by the narrator’s friend:

Dr. Gaudenzi’s wife informed me that she was a very rich but batty old woman who spent her time smoking cigarettes in an ivory holder and studying Sanskrit, and that she never saw anyone except a Dominican friar who came every evening to read her the Epistles of Saint Paul.

As Alberto and the narrator spend more time together, Alberto remains distant, and he declines to invite her to his home because of his mother’s peculiarity. But eventually the “batty old woman” dies, and Alberto and the narrator are married. She quits her job and goes to live with him, and they have a baby. Yet all is not right with what might on the surface appear to be a happy family. Thus the series of events leading to the murder.

In its riveting plot and formal precision, The Dry Heart feels in many ways like a stronger piece of writing than Happiness, as Such, which sometimes meanders and is hurt by Ginzburg’s questionable decision to move in and out of the epistolary format, with some characters appearing in close third person and others only in letters. But Happiness, as Such, written much later in Ginzburg’s career, brims with a wisdom that the novella lacks. It’s as if, when she wrote Francesca’s comment in The Dry Heart, she had yet to fully reconcile the meaning of family in her fiction. In the earlier book, families are vises from which one inevitably seeks to escape; the horror comes when you realize there’s nothing else out there. Meanwhile, Happiness, as Such reckons with the knowledge that the family, however terrible an invention, nevertheless may be the best means of support, comfort, and at the very least, entertainment, in our too-often-brutal world.

More Reviews