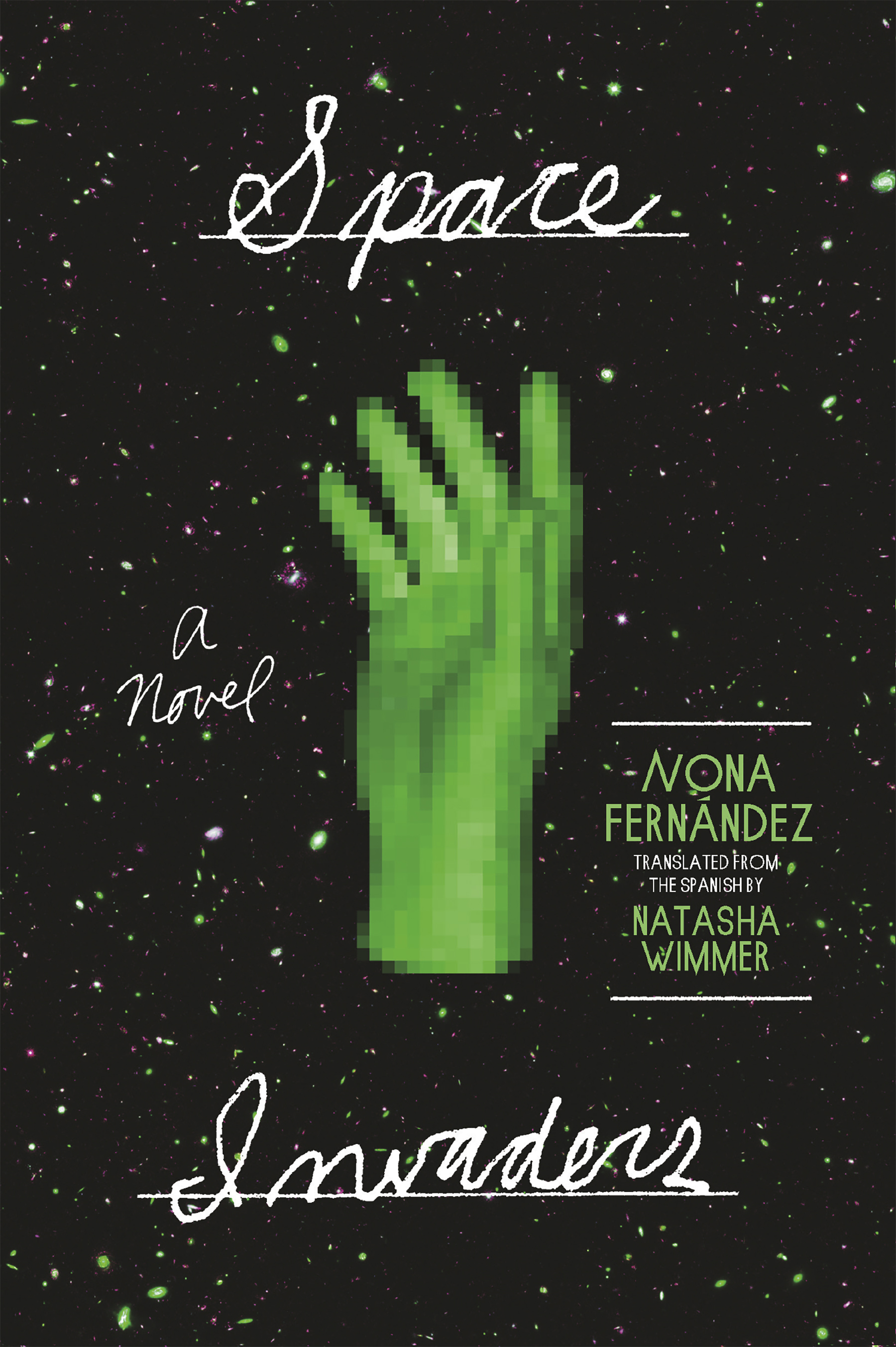

Space Invaders: A Novel by Nona Fernández

Reviews

By Robert Rea

Late last year hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets of Santiago, protesting decades of corruption and inequality. In a letter from the front lines, author Nona Fernández referred to the inevitable crackdown by those in power as “authoritarian déjà vu.” What she means by that gets fleshed out in her first novel available in English, translated by Natasha Wimmer. Space Invaders is haunted by the history of state-sponsored violence and the fear that Chile may be doomed to repeat it.

Fernández has much in common with fellow Chilean novelist Alia Trabucco Zerán. Both are part of a generation that came of age in the shadow of Pinochet’s dictatorship. In an interview with SwR, Zerán was asked how violence and politics inform the young people’s lives in her novel, The Remainder.

I think for many, not only for me, violence, childhood, imagination, and politics were all mixed up in a singular way. This is something that shapes the characters’ subjectivities and their struggle with their own present, and it probably shapes my generation in ways we still haven’t quite figured out.

Whereas The Remainder spins outward, following three teens on a road trip across the Andes, Space Invaders turns inward upon the childhood memories of a now-grown group of friends. But for all their differences, the two are one in that they’re about kids caught in long cycles of violence and trauma.

Space Invaders unfolds in a series of flashbacks. As the memories are recalled, the innocent curiosity of children assumes a sinister edge. Take, for instance, the missing hand of one girl’s father. How and why he lost the hand—while working as a strong man for Pinochet, it turns out—barely registers at all. And then one day she disappears. To tell more would give too much away, but it’s enough to say her friends are puzzled by this until the truth is revealed, to their horror, many years later. The way the author closely guards the secrets of the adult world brings to mind Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go. But Space Invaders never goes full blown sci-fi, despite the iconic image of its title. Instead, it defines a whole generation that’s grown up under authoritarian rule.

While it’s true that this is a book about Pinochet’s Chile, mostly it’s about loss, grief, and the frustration of being swept along by the forces of history. At school the children march “in a long single file line down the middle of the schoolyard. Next to us is another line, and then another, and another. We form a perfect square, a kind of game board. We’re pieces in a game, but we don’t know what it’s called.” At home they hurry through homework on “Chile’s never-ending battle with Peru and Bolivia,” all so they can spend hours fending off wave after wave of pixelated alien invaders. Gradually the novel draws parallels between the onscreen action and real-world political struggles: “And when the last one died, another alien army appeared from the sky, ready to keep fighting. They gave up one life to combat, then another, and another, in a cycle of endless slaughter.”

For such a quick read—clocking in at a brisk seventy pages—Space Invaders has the kind of historical sweep more often found in a big, fat novel. My guess is this has something to do with what Zerán says about Chilean writers of her generation. Fernández writes intimately about growing up in a volatile political era, and yet to call Space Invaders a coming-of-age story implies growth, sequence, resolution. All this could be said of the characters, but what we’re supposed to take from the long arc of history is less obvious. In the closing pages, a more mature, grown-up version of the narrator explains,

Time isn’t straightforward, it mixes everything up, shuffles the dead, merges them, separates them out again, advances backward, retreats in reverse, spins like a merry-go-round, like a tiny wheel in a laboratory cage, and traps us in funerals and marches and detentions, leaving us with no assurance of continuity or escape.

As kids we’re taught that history can be gleaned from a textbook, but as Fernández points out in her letter, learning from the past is a different thing altogether. After reading and liking this book a lot, I can’t help but think we don’t learn much at all.

Robert Rea is the Deputy Editor & Web Editor for SwR.

More Reviews